A chance encounter with an L.A. property where Swami stayed briefly in 1899–1900 launched me on a path of personal rediscovery

by Nikhil Misra-Bhambri, California

Janmashtami, the celebration of lord Krishna’s birth, brings out crowds all over Delhi, as temples overflow with devotional singing, dance, drama and recitations of the Bhagavad Gita. As a six-year-old boy visiting from America, I am overwhelmed. My aunt and grandmother are very protective of me, and try to explain the significance of the noisy, colorful crowds. Their concern changes to amazement when I suddenly recite to them Krishna’s entire life story.

Amar Chitra Katha comics and Balvihar gatherings had captured my attention at home in Pasadena, California, making me a walking encyclopedia of Hindu Gods and Goddesses. But while my Indian relatives were amused at my enthusiastic recitations, my schoolmates, who were mostly Caucasian and East Asian, found me odd. To gain their acceptance in elementary and middle school, I immersed myself in Pokemon and Star Wars with the same intensity I had brought to the comic book legends. Striving to be cool, I even embraced the world of gangsta rap, hood movies, urban dressing and “getting turnt up” (partying). Slowly, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva receded into the background.

Living in South Pasadena, a suburb of Los Angeles, I often drove down the city’s main thoroughfare, Monterey Road. At one end, on the town’s outskirts, lies Foremost Liquor Store. Run by Indians, it attracts young adults and underage drinkers with fake IDs. The first time I went there with friends, I noticed a vintage Victorian home obscured by the store’s dominating facade. Curious, I walked to the house and discovered that it was a designated historic landmark, a one-time residence of Swami Vivekananda back in 1900. Digging deeper into his story, I learned that he had spoken at Castle Green, a fancy wedding venue, in Pasadena’s bustling Old Town. These disparate events began for me a journey of rediscovery, almost 15 years after my Janmashtami experience in Delhi. I think I was destined to rediscover myself by discovering Swami Vivekananda.

My cousin, Vivek Saraswat, is a group product manager at Google, and a Silicon Valley native. He learned about Vivekananda when he had to do a project in elementary school about a namesake. He recalled, “The misconceptions held by many Westerners at the time of Vivekananda’s visit helped me better understand my own Indian American identity. Today, living in modern California with many Indians, we take a certain level of awareness about Hinduism for granted. However, this was not the case when Vivekananda visited. He was a trailblazer who created the awareness from which future generations of Indian immigrants benefited.”

Vivek’s comment led me to listen to a modern dramatic rendition of Vivekananda’s iconic speech at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago in 1893. I was riveted as I heard his fearless declaration, “I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and refugees of all religions and nations of the Earth.”

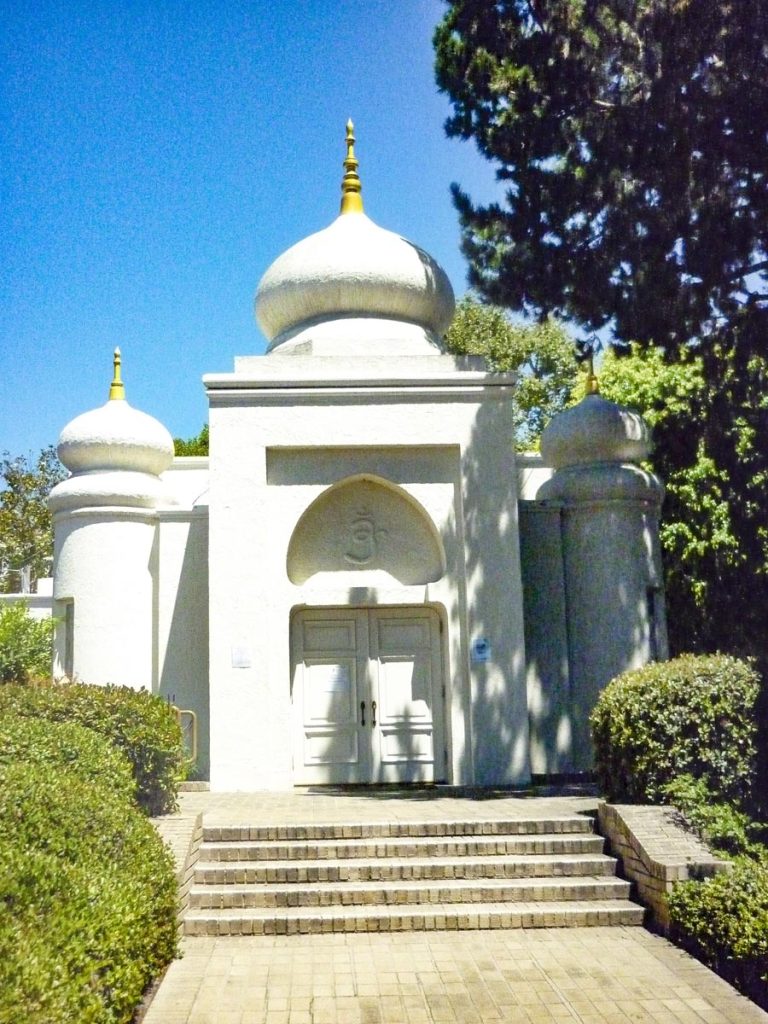

Eager to learn more, I visited the Vedanta Center in Hollywood, just in time to hear Swami Sarvadevananda, the current spiritual leader of the Vedanta Society of Southern California and a monk of the Ramakrishna Order since 1965, deliver his Sunday morning lecture. Towards the end, an attendee asked, “I am from a nation which is ruled by a tyrant, and many citizens have had to flee our homeland. How can we love the God in someone so cruel?”

Sarvadevananda replied, “Vedanta says inner light is everywhere but may be covered by tamas, darkness, which results in a brutal mind. If we can do something to take out someone’s brutality, then do that, but, if we cannot, then we shall respect the Lord inside them, not the whole package. Here seeing God means that you see the inner light. As one moves in spiritual development, you can see behind good, evil, holy and unholy. The one spiritual truth resides everywhere. Only appearances are darker, lighter, happier, joyful or miserable. Spiritual practice means cleaning the mind, emotions, the darker aspects of our personality. When those are clean, all becomes all, and the sinner will be a saint.”

Trying to understand how different people interpreted Vedanta, I spoke with several in attendance, the first was a young Indian Bengali American whose family’s involvement with Vedanta dated back to his grandparents’ days in Kolkata. He told me, “One of the things that continues to attract me to Vedanta is its intent and actions to foster religious unity. It is the direction humanity must go towards; the idea that we are all one.”

Another was Ellis Fowler, a young African American actor and personal trainer who frequently attends sessions at the center. After studying different spiritual traditions, he found that Vedanta best resonated with him. He told me, “I like how Vedanta embraces every part of a human being. I was born and raised Christian but I realized that a lot remained unexplored, and much of the human self was rejected.” He continued, “Realizing that the God in me is the same as in everyone else really opened me up in terms of compassion, love and awareness of my own actions and life purpose. As an actor, I am now able to look at a character in a deeper way than before.”

The people I spoke with displayed a certain peace and serenity. Was it their belief system? Was it daily meditation practice? I wanted to feel the peace and serenity myself, but was unsure about what specifically I should do. So, I asked Swami Sarvadevananda what Vivekananda would say if I said that I don’t know what to believe.

The elder monk replied, “If you ask yourself ‘Who are you?’ you do not need to think of God and what you believe. You are Nikhil now in a waking state. When you sleep and dream, this Nikhil goes away, but you do not actually go away. You say, ‘I dreamt.’ You are the observer of your dream. When you sleep, you say, ‘I slept.’ So, Vedanta would say you do not need to believe in something called ‘God,’ but if you believe in yourself, there is always someone as ‘I’ observing everything. The observer is always separate from the observed. You are the observer, the ‘I.’ Vedanta would say ‘find that “I,” we cannot ignore it.’ Yesterday, today, after one month we always say ‘I’ because that I’ is the same. That ‘I’ is called consciousness and eternal reality. In loving terms, we call it God.”

The message that comes through again and again is that there is Divinity in everyone. But why do I not see it? When I am struggling to understand something abstract, I sometimes call Mark Kriger, a friend of my father who has become my mentor over the years. He immerses himself in several spiritual traditions and has been a frequent visitor at Ramana Maharshi’s ashram in India. Mark told me, “Self-inquiry is the most important. If we keep returning to the thought ‘Who am I,’ then we become one with that awareness. Many people are motivated by wealth, achievement and power in order to attain happiness and fulfillment. However, the process of self-discovery is unending. Advanced yogis have found that there is no level of materialistic achieving where we ever enter a state of real peace. Thus, the key is to be aware of that which is awake to everything, which is the Self.”

Vivekananda emphasized in his writing, “God in Everything,” divisions between humans and nations are simply due to our own ignorance. He stated, “Vedanta says this separation does not exist, it is not real. It is merely apparent on the surface. If you go below the surface, you will find unity between man and man, between races and races, high and low, rich and poor, Gods and men, and men and animals. If you go deep enough, all will be seen as only variation of the One.”

As I learn more about Vedanta, I realize that I have been exposed to this philosophy from the time I was a child. I grew up taking pride in India’s religious and ethnic diversity because that is what my maternal grandmother modeled every day. Though she personally suffered the horrors of India’s Partition, her music teacher was Ustad Iqbal Ahmad Khan, a Muslim from the Delhi Gharana tabla teaching tradition, whom she treated like family. One of my treasured childhood memories are her practice sessions in her living room in Delhi with Khan and his musicians. Even today, Muslim singers recite Hindu chants at our family religious functions.

I often re-read Vivekananda to see which words and sentences resonated with me. The most impactful lines for me are “the Christian is not to become a Hindu or a Buddhist, nor a Hindu or a Buddhist to become a Christian. But each must assimilate the spirit of the others and yet preserve his individuality and grow according to his own law of growth.” I realize that I had not always followed this path. Instead, I had been pulled by superficial differences. Even recently, as an undergraduate at University of Southern California, I had become increasingly distant from my birth faith. As I searched for social acceptance, I joined different religious groups based on whether they had an active social community, and I tried to follow their customs and practices. Briefly, I even “converted” to different religions. Over time, I became increasingly stressed, because for the sake of being accepted by others, I was contradicting my innate nature. Slowly, I realized that I could not force something unnatural upon myself for the sake of social popularity. Rather, I had to start from within myself, by understanding who I was at heart, and the rest would fall into place. I had to believe that I had Divinity inside me.

Today, twelve years after I lived in South Pasadena near “Vivekananda House,” I am studying to become a special education teacher, employing the fundamentals of Swami’s teachings to help severely disabled and emotionally disturbed students believe in themselves. It will be a journey, maybe without an end.

Nikhil Misra-Bhambri is a freelance journalist living in Los Angeles, California. He is a graduate of USC with a bachelors in history, an avid reader and traveler who is always keen to write about ethnic groups, culture, cuisine and history. Email: bhambrin3@gmail.com