By VRINDAVANAM S. GOPALAKRISHNAN

Two thousand and more timber temples dot Kerala’s verdant landscape. Devotee’s devotion have created them in equal numbers to Lord Siva, Lord Vishnu and the Goddess. Yet somehow this is especially Siva’s land. Among His temples famous and popular are the Mahadeva temples at Chengannur (Alappuzha), Ettumanoor, Kaduthuruthy and Vaikom (Kottayam), Ernakulam in Kochi City and Vadakkumnathan (Mahadevar) in Thrissur. Whether by daily puja or elaborate rituals and festivals, these temples are the mainstay of religious life for twenty million Keralite Hindus.

When it comes to festivals, nothing surpasses Porram, one of India’s most spectacular. It is held every April before the abode of Lord Siva at Thrissur. A hundred thousand people attend the non-stop, thirty-hour celebration featuring one-hundred gold-caparisoned elephants and concluded with fireworks costing US$150,000. On this day all the Deities of ten neighboring temples–mostly of the Goddess–visit Lord Siva, Vadakkumnathan, (“North-facing Lord”), each upon Her or His own elephant. The high point is the hour-long divine kudamattorn, a competition wherein mahouts upon two rows of fifteen caparisoned mighty tuskers face each other offering a rapid changing of fans, umbrellas and other decorations from atop their elephants.

But festivals are grand only while they last; for inspiration and solutions to the mundane problems of life, devotees seek Siva’s help closer to home. Consider the plight of an unnamed socialist-minded professor at a major college in Kochi City. Despite his best efforts, no suitable marriage alliance had been found for his daughter, who was fast approaching thirty. Ignoring the father’s protests about “superstitious ritual worship,” her mother, also a senior college teacher, took her to the monthly Mangala Gauri Puja (photo, page 28) conducted at the Pavakulam Siva Temple in Ernakulam. The goal? A very unsocialist plea for divine intercession.

Mangala Gauri Puja offers three results: finding a husband, bearing a child and having a long marriage. As in many of Kerala’s temples, it incorporates vaidhyavidhi, ayurvedic preparation of medicated and sanctified ghee given as prasadam (sanctified offerings). For three days preceding the puja, women observe a strict vegetarian diet, recite “Aum Nama Sivaya” 108 times morning and evening after lighting a lamp and avoid all wrong thoughts. At least ten ladies were recently blessed with marriage after attending just three pujas, the event’s organizing secretary reports. And what about the socialist professor’s daughter? “In a fortnight, to our surprise, a suitable proposal came up, and both the families have accepted it,” reports a family member. This temple also conducts a monthly abheeshta bhala siddhi yagnam (roughly, “ritual resulting in fulfilling of ambition”). Begun just last year, it now attracts so many devotees–more than ten thousand–that closed-circuit TV was set up to broadcast the ceremony to crowds gathered in and around the temple.

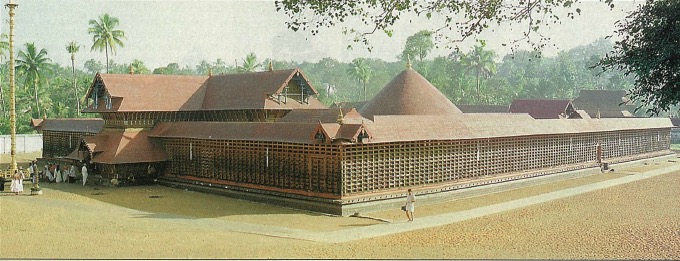

Kerala has some 700 Siva temples, spread from Shucheendram, now in Tamil Nadu’s Kanyakumari district, to Kasargode in the North bordering Karnataka. Most are built of wood in the unique Kerala style. Sixty are classified as major temples and occupy a large area with compound walls surrounding the chuttambalam (building constructed around the sanctum sanctorum). The roofs are made of treated hardwood (teak and rosewood) and covered with copper sheets. Up to 100,000 deepa (oil) lamps are permanently mounted on the compound walls. Kerala’s temples are uniquely warm, friendly and accessible. One feels the presence of the Deity immediately upon drawing near, unlike the experience of approaching some of the great stone temples of Tamil Nadu.

Krishnam Embranthin, a temple head priest, says, “All of these temples were rich until 80 years ago, but now 80% cannot meet day-to-day expenses.” When the temples were built by the rulers of various small princely kingdoms, adequate cultivable land was allocated for meeting expenses. But since the arrival of the British and the subsequent creation of secular India, 90% of the temples have lost their wealth, according to Jagatguru Sathyananda Saraswati. He is Madadhipathi (head) of the Sree Rama Dasa Madom, near Thirvananthapuram and also chairman of Hindu Ikyavedi (United Hindu Forum) which seeks to transfer control of the temples from the government to Hindus.

The temple’s lands were encroached upon by neighbors, and then legally transferred to the encroachers as part of 1960 government land reforms. Thus, explained Swami Sathyananda, many temples have no property except the acre of land upon which they sit. All these temples are now controlled and administered by Devaswom Boards, statutory bodies constituted by the government for this purpose–as is the case in all other Indian states. Only Hindu temples are so controlled; other religions manage their property and affairs without government oversight. Swami Sathyananda said the temple revenue collected by the boards goes to the government treasury and is utilized for purposes other than those of the Hindus–one main reason, he believes, behind the poor maintenance of most temples. Also trade unions formed among temple staff have resulted in a significant number of communists working in the temples and a consequent loss of sanctity, according to Swami.

The Hindu Ikyavedi has now created a “Kerala Devaswom Board” administrated by Hindus which seeks first to oversee all the private temples left in the state (about 300 small rural sanctuaries), and then to take over the rest–at least 2,000–from the government. But given the trend in India, where major temples such as Tirupati have just come under complete government management, such transfer is unlikely. Some devotees don’t wait for administrative reforms. The Kaduthuruthy Sivan temple was in a neglected state but with the concerted efforts of a few devotees, is being renovated at a cost of US$35,000. “The money just pours in from the devotees. It is the grace of Lord Siva,” says Mr. Kaimal, president of the renovation committee.

It is especially auspicious to visit the three Siva sanctuaries of Ettumanoor, Kaduthuruthy and Vaikom all in one day. Ettumanoor, in particular, is famous for the miraculous cure of epileptic fits and stomach ailments. “Lord Siva saved my life,” says Puramattom Mani. He suffered fits after contracting cerebral malaria in 1973. “Even after undergoing ayurvedic and allopathic treatments for years, there was no cure, and the frequency of fits increased. I even considered suicide. Then I took refuge in the Ettumanoor temple in 1978 and in a couple of weeks I was cured. Ever since then I never had any attack of this disease. My family and I are fully indebted to the lotus feet of Lord Siva,” said Mani.

The princes of erstwhile Travancore and Cochin states built Siva, Vishnu and Sakti temples throughout their kingdoms. With proper maintenance, these wooden structures last easily 300 years. The challenge now for the Hindu community is to continue to invigorate and care for the temples, and erect new ones. Preferably these will be in the traditional wood style, although concrete (cheap and fireproof) is gaining ground. The true miracle is that even after centuries of Christian and Muslim incursions, and decades of communist rule, Hinduism in Kerala has not only remained strong but is actually in resurgence.

THE LORD’S WOODEN WONDERS

PRINCESS ASWATHI THIRUNAL GOURI ON KERALA’S TEMPLES

Kerala temples evolved from the residential form, this metamorphosis from house to temple being unique to Kerala and not seen anywhere else. These temples, hence, were brought within human scale and endowed with visual modesty. The concentric development of Kerala temples with the Sreekovil (sanctum) in the middle of the central open courtyard surrounded by a row of built-up spaces is identical to the traditional nalukettu, the Malayalee home. Instead of the vertical expansion favored elsewhere in India, these temples, as do the homes, favor axial or circumferential expansion.

The temple’s simplicity of style and subdued coloring are a complementary contrast to the lush rainbow background nature has provided for this enchanting land. Its conical roof with copper or clay tiles crowning the central sanctum has a generous slope, for Kerala is the delight of the rain god.

Ornate figures, themes and patterns are intricately carved in the wooden ceilings and beams and painted along the walls in a running canvas of multiple scenes.

In keeping with the fundamental simplicity of concept of the Malayalee mind, the outer entrance had padippuras, simple single or double-storied stylized, tiled wooden structures instead of the ornate, imposing rajagopurams (entry towers) favored in the other South Indian states. The most important auxiliary buildings, especially since the 15th century, are the beautifully worked koothambalam, halls for dance and music.

Her Royal Highness is a member of the royal family of Travancore–one of the great builders and benefactors of Kerala’s Hindu temples.