By Dev Raj Agarwal

The dull and time-worn face of Gomti Ben has suddenly come to life, and I can discern the relief in her pale eyes as the Panda, her family priest, approaches. “I can now die peacefully,” she sighs heavily, as Panda Virendra Bhardwaj makes offerings in memory of her dead husband. Then, in a long, double-folded register called a pothi, he enters the names of all the boys born in her family since the last entry, when her husband fell to some unknown ailment in a remote Rajasthani village over 25 years ago. Although there are 2,500 pandas who find their livelihood on the banks of the Ganga here at Haridwar, it took the illiterate Gomti and her relatives just minutes to locate Bhardwaj–so well networked are the Pandas.

Hindu families typically use priests from their local vicinity to perform the rituals and sacraments that tradition requires of the family. But what to do when far away on pilgrimage in Haridwar? Enter the Pandas–a clan of brahmins conversant with the rituals of the pilgrim. “We work as guides in an alien land,” explains Ram Kumar Upadhayay, a Panda on the Har ki Pauri ghat. “We offer accommodations and food and access to many dharmasalas. It is our business to see that our clients remain happy and trouble free,” he says.

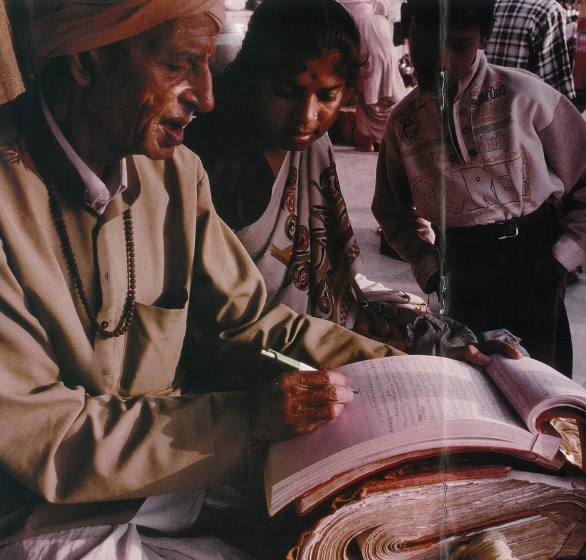

Pilgrims to Haridwar are obliged to make offerings to deceased ancestors, especially paternal, as well as to make offerings to Mother Ganga and ritually bathe in the holy river. The Panda oversees and assists in all of this. But many enlist the Panda for other rituals as well. Along the main ghat, barbers clean-shave the heads of little boys while Pandas chant mantras nearby, and the tender coils of hair meander freely downstream. Services complete, the Panda then opens the pothi. Using an index of villages and castes, he instantly finds the page detailing the lineage of the pilgrim, and he updates the record.

Apart from being a historical document, the pothi is considered authoritative by courts of law and is referred to in matters of distribution of property in Hindu families. Each Panda has records as old as four hundred years, but carries about registers of just one century. Older records are preserved at home, and these can be easily examined upon the request of the pilgrim.

For any Panda, knowledge of the Shastras is a must, and the foundation is laid at home. At least one of the sons from the family has to take up the father’s profession. The number of Pandas here has diminished from near 5,000 to about 2,500 in the last few years. But Bharadwaj remains positive. “Haridwar is in easy reach of people now. There are trains, buses and cars and an unending caravan of pilgrims.”