By Mark Hawthorne

While tattoos among sailors and motorcycle clubs might seem the most obvious to someone living in the West, many cultures, including that of the Hindus, have long regarded tattoos as essential aids in lifeand even as passports into the world beyond death.

So why tattoos? What does a symbol embedded under the skin have to do with the spirit? In part, it is related to self-mortification, which has a long history in religion. Whether it’s a Buddhist lama drawing a blade across his tongue, a Lakota warrior hanging for hours by hooks puncturing his chest or a sadhu piercing his cheeks and tongue with small spears, nearly every culture has a sect that regards physical suffering, or an apparent indifference to it, as just another step in spiritual development. Tattoos are believed to have begun as cuts in the skin to form scars, a decidedly painful process. The color, from soot or plants, came later. Anthropologists believe tattoos are part of the evolution of a tradition that views the voluntary endurance of pain as a way to tap into a primal urge for meaning and belonging. And sacred symbols, from cave paintings to mandalas, are as old as the struggle to understand our world.

Tattoos are nearly as old. Archeologists have found instruments in Europe that were probably used for tattooing that date back as far as 40,000 years ago. In 1991, when a German couple hiking near a glacier in the Italian Alps stumbled upon the remains of a 5,300-year-old man, they discovered more than a Neolithic iceman. “Otzi,” as scientists dubbed him, was frozen evidence that the practice of tattooing predated earlier tattoo discoveries by more than 1,000 years. Anthropologists speculate that Otzi’s tattoos a cross on the inside of the left knee, six straight lines six inches long above the kidneys and numerous parallel lines on the ankles must have been personal symbols, not identification marks, since they would have been covered by his clothing. No one can be sure what Otzi’s tattoos meant to him. Some scientists have observed the marks found on Otzi correspond to acupuncture points and speculate his tattoos show he had been treated for pain or illness. It is certainly no coincidence that acupuncture involves ritesneedles under the skinakin to the practice of tattooing. Anthropologists believe that tattoos have always had a religious and spiritual significance.

Devotional Tattoos: Religious tattoos can be viewed with two levels of devotion: there’s the ordeal of receiving the tattoo the tedious and painful process of injecting pigment into the flesh and then there’s the symbolism and color of the design itself.

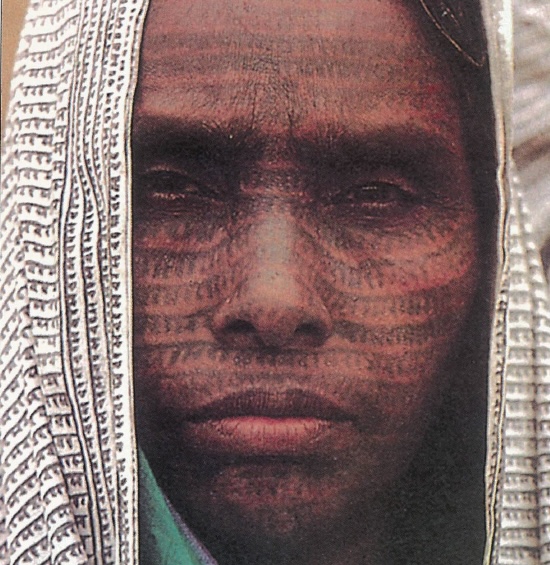

Among the most devoutly tattooed groups anywhere is the community of Ramnaamis. Scattered across the Indian states of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, this sect of untouchables found refuge from harm in their distinctive tattoos the name “Ram” repeated in Sanskrit on practically every inch of skin, even on the tongue and inside the lips. Ramnaamis began their extraordinary custom during the Hindu reformist movement of the 19th century when they angered the upper-caste brahmins by adopting brahminical customs. To protect themselves against the brahmins’ wrath, the Ramnaamis tattooed the name of Lord Ram on their bodies. About 1,500 strong today, the Ramnaami community still practices this painful rite, which is as much a demonstration of devotion as a talisman against persecution.

With a rich tradition and thousands of Deities, Hinduism itself is today the source of countless tattoo designs. Tattoos depicting popular Gods such as Siva, Ganesha and Kali or sacred symbols like “Om” adorn the flesh of Hindus and non-Hindus alike. Some of the most elaborate tattoo patterns anywhere are on the women of the Ribari tribe of Kutch, the very region in northwest India just devastated by an earthquake. It is one of the places to which the Pandavas were exiled during the Mahabharata. The members of the nomadic Ribari tribe live as their ancestors did; their tattoos being tangible symbols of the people’s strong spirit and concern with faith and survival.

Today, many people choose a particular design not because of its power or religious significance, but because they simply like the look of it. Tattoos are borrowed from other traditions as well, including Native American and Buddhist. These tattoos for fashion, of course, should not be regarded as religious and are often offensive to those who understand that spirituality is not simply a decoration. And beware of getting a tattoo designed in an unfamiliar language. Last year a man in England had a tattoo artist inscribe his wife’s name on his arm in Hindi. Local Hindi speakers spotted the tattoo and informed the man there was a spelling error.

Tattoos and the afterlife: As cultures focused more on spiritual issues, tattoos took on an active function, especially in the Pacific Islands and North America. The Maoris believed that a spirit would recognize their elaborate facial tattoos after their death and give them the vision to find their way to the next world. The Dayak tribes of Borneo thought their hand tattoos would illuminate the darkness of the afterlife as the soul searched for the River of the Dead. Maligang, the spirit guarding the river, would check for the tattoo, which earned the soul the right to cross the river. This is similar to the Lakota tradition, which teaches that the soul ofthe dead starts its journey to the other world on the starry spirit road (Milky Way). Along the path, it will pass Owl Woman, who inspects it for the tattoo. If she can’t find it, she prevents the soul’s passage. The Inuits of Alaska also tattooed themselves in preparation for death rituals. Small dots were applied to the pallbearer at various joints along the body to protect against evil spirits.

Some believe that the soul resembles the body that houses it and retains this appearance even after death, including the person’s tattoos. In other cultures it is believed that death changes the person’s appearance so drastically that your tattoos were the only form of identification that will be left to you. Without tattoos you are doomed to wander forever in the afterworld.

“In all ancient societies religion and ritual were a part of every activity,” says Steve Gilbert, author of Tattoo History: A Source Book (New York: Juno Books, 2000). “Religion was an integral part of all daily activities, so it was not that tattooing in and of itself was religious, but all activity was defined, controlled and limited by taboos, and overseen by spirits. Tattooing must have served as a symbolic connection between the individual, the group and the Gods. I think it was especially potent in this regard because of the letting of blood and the permanent changing of the body. The designs, of course, were strictly prescribed by tradition.”

Tattoos for Protection: Many cultures regard tattoos as protective amulets, and such magical applications are closely linked to religious beliefs. Ainu women in Japan, for instance, tattoo themselves with images of their Goddess, which is able to repel evil spirits and thus protect from disease. Iraqis commonly tattoo a dot at the end of a child’s nose to guard against illness. A tattoo of Hanuman is used to relieve pain among Hindus. Aborigines in Australia believe tattoos on their arms allow them to dodge boomerangs. Soldiers in Burma tattoo their thighs to be invulnerable in war, and Cambodian men cover themselves in tattoos to make themselves impervious to harm, even from bullets. The use of tattoos in Cambodia may have come centuries ago from Indian settlers who practiced Vedic rituals.

Sacred Buddhist texts are a favorite tattoo in Thailand, where they are believed to have magical power. In an initiation rite known as the “Krob Kru,” the devotee lights incense and prays in preparation. The tattoo artist uses a special rod to inscribe the sacred text on the chest, back or arms. A shaman then tests the tattoo’s potency by giving each tattoo three or four strong swipes of a sword. Tattoo recipients often enter a state of ecstasy or burst into violent trances.

The snake clan of Pakokku, Burma, has made a science of protection tattoos. For centuries these Buddhist snake handlers have tattooed their bodies to protect themselves against the vipers and cobras that share their town. But they hold these deadlysnakes in high esteem: Buddhist legend tells of a giant cobra sheltering a sleeping Lord Buddha during a rainstorm, and there is even a snake pagoda in nearby Mandalay. The town also regards the snake as its fertility God. Currently about a dozen members strong, the snake clan of Pakokku claims that no member has ever been killed by a snake no small feat considering these men are responsible for capturing snakes by hand and releasing them unharmed miles from town. Their secret is the tattoo. Each member undergoes weekly tattooing, a ritual that involves prayer, a very large metal needle and black ink mixed with snake venom. The venom, collected from snakes found in town, acts as an inoculation against snakebite. Arms, legs, chest, back, face and even the scalp are tattooed with Buddhist symbols, each mixed with venom cobra venom for tattoos on the upper body, viper venom for the lower body to help build the bearer’s antibodies.

The Hawaiians are prominent among peoples who have specific tattoo Gods. Called ‘aumakua, these family or personal deities can be protective when properly honored, or destructive if neglected. Like Native American spirit guides, the ‘aumakua can take the form of animals, inanimate objects or even natural phenomena, like lightning and thunder. Many Hawaiians adorn themselves with special tattoos honoring their ‘aumakua. A tattooed row of dots around the ankle, for example, is considered a charm against sharks thanks to an ancient story in which a woman swimming in the ocean was bitten by a shark, her ‘aumakua. When the woman cried out, the shark let go, saying, “I will not make that mistake again, for I see the marks on your ankle.” In Hawaii, the images of the tattoo Gods are kept in the places of tattoo priests. Each tattoo session begins with a prayer to the tattoo Gods that the operation might not cause harm, that the wounds might heal soon and that the designs might be handsome.

Like most of the Pacific Islands, Samoa also has a rich tattoo tradition. “In ancient Samoa, tattooing played an important role in both religious ritual and warfare,” writes Gilbert. “The tattoo artist held a hereditary and privileged position. He customarily tattooed young men in groups of six to eight, during a ceremony attended by friends and relatives who participated in special prayers and celebrations associated with the tattooing ritual.” The tattoos of Pacific Island natives made an impact on English explorers notably those who sailed with Captain Cook late in the 18th century and they returned home with bold new designs and helped resurrect the tattoo art in Europe.

Western Tattoos

Dispite tattoo’s growing popularity, one of a mother’s worst nightmares remains her 15-year-old daughter coming home one day and saying, “Hi mom, check out my new tattoo.” Throughout American and European history, tattoos have mostly been considered just for sailors, criminals and, most recently, gangs. One exeption was a short vogue in the English upper classes in the late 1800s. Another revival started in the 1990s, bringing back interest in both traditional and nontraditional tattooing for both ethnic groups and tattoo fans.

Temporary Tattoos

Though tattoos are by definition painful (the word comes from the Tahitian word “tatau,” which was the sound their tattooing instruments made), some tattoos are applied without pain and last only a short time. A popular tattoo art in India ismehendi,a plant-based temporary tattoo involving thin lines for lacy, floral and paisley patterns covering entire hands, forearms, feet and shins. In Hindu weddings the bride often decorates her palms and feet, believing that the slower the color fades away, the more she is loved by her husband. Archaeologists have discoveredmehendiorhennaon the hair and nails of Egyptian mummies. There is evidence that the Neolithic people of Catal Huyuk (in central Turkey) usedhennain the 7th century BCE to adorn their hands in connection with their fertility Goddess. Their Goddess worship was the predecessor to the religions in the ancient Middle East, andhennaseems to have been used throughout this region. After 1500, henna is depicted on women in paintings in India and is also present on Kali and other Hindu Deities. The first known Indian queen to have been painted with the paste was Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of Emperor Shah Jahan, for whom the Taj Mahal was built.

mind blowing tale of tattooing