By Lavina Melwani

There is an eerie stillness to the images, a strongly felt presence of a higher power. Be the subject Ajanta, Sarnath, Khajuraho or Vijayanagar, Japanese photographer Kenro Izu captures the very soul of these ancient places of worship. It is hard to believe that these pictures are taken in the past two decades, for the landscapes and architecture look as they must have in the 19th centuryÑcalm, unruffled, unmoved by human presence.

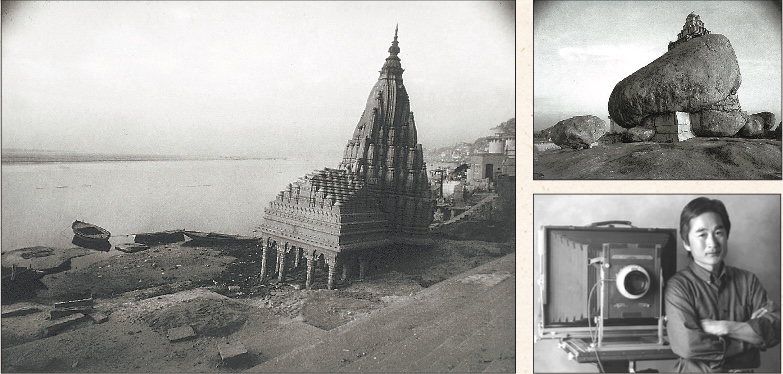

Born in 1949 in Osaka, Japan, Izu studied photography in Nihon University, College of Art in Tokyo and moved to New York in 1971. He began working with the complex platinum/palladium process in 1981. He is considered one of the finest practitioners of this early black-and-white photographic medium, notable for its permanence and extremely wide tonal range. New Yorkers got to see Izu’s images at Sepia International and at Howard Greenberg Gallery during the fall season. They are now showing at the Arthur Sackler Gallery in Washington.

In an age when cameras are becoming smaller, Izu in the tradition of 19th century photographersÑtravels with 300 pounds of equipment, trekking to remote places to expose his large format platinum plates. A Buddhist, Izu is drawn by the spiritual traditions of different faiths and has documented Buddhist and Hindu sites in India, Cambodia, Burma, Vietnam and Indonesia, including Angkor Wat, Borobodur in Indonesia and Buddhist monuments in Mustang, Ladakh and Tibet. One trip that was cut short was the highly precarious journey to Kailash. Izu hopes to return there with all his paraphernalia.

Like the 19th century British photographer Samuel Bourne, who documented the Himalayas while traveling with porters loaded with boxes of equipment and supplies, Izu carries a custom-built large-format view camera that produces a 14″ x 20″ negative. He said, “To capture the spirituality I feel in stone remains and the density of the atmosphere that embraces them, I can think of no other medium than platinum prints made by contact printing with large format negatives.” One expert jokes that Kenro has found the absolute hardest way in the world of taking a photograph.

Although Izu photographs some of the most crowded religious sites, he manages to clear the frame of all human existence and make the image a testament to God and nature. His photograph of a famous, much photographed site in Benares is calm, eerily empty of human frenzy and catches the sheer beauty of the place (above). Recalled Izu, “It was photographed at the last light of the day. I saw a cremation of a body for the first timeÑand long after that I was thinking, ‘What is life all about?'”

Izu’s images are about patience and perseverance, of waiting and waiting for the perfect moment when light and atmosphere embrace. In Benares there is human chaos, but Izu waited till the noisy crowds dispersed and quiet settled on the dying day: “It’s always the moment I’m looking forÑafter the sun set and the horizon on the western side of the sky suddenly grew lighter, and the light just made magic.”

He was fascinated by Hampi, site of the Hindu kingdom of Vijayanagar in South India that flourished from the time of Marco Polo to 1550. “Very few people have photographed this site,” he said. “There is nothing like this in the world. Mile after mile you see huge rocks sitting sometimes very artificially, as if someone had balanced them. I thought of Krishna who is known for His playfulness and also His mighty powers. I told myself this is Krishna’s playground, because it seemed as if the God had been playing ball and rearranging the rocks.”

“I am not an artist. I’m a photographer.” he said. “Creation of something new is not my interest. I like to observe very closely, very deeply, and document it as accurately as I see it, in my own way. This is my inner trip for myself, if I may say searching for myself. I’m curious to see where I end up, but right now I’m drawn toward the Himalayas. I started to realize that I’m trying to look into myself.”