By Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami

Conditions in the world today are certainly troubling—wars between countries, wars within countries, plus a growing threat of international terrorist acts. The shocking attacks in New York on September 11 naturally heightened everyone’s concern about these problems.

One of the immediate consequences of 9/11 was the television coverage depicting people in a number of countries who do not much like, some even strongly hate, the United States, even to the point of wishing violence upon it. Watching these startling reports on television, we were again reminded of the extent and seriousness of the problem of prejudice in the world today.

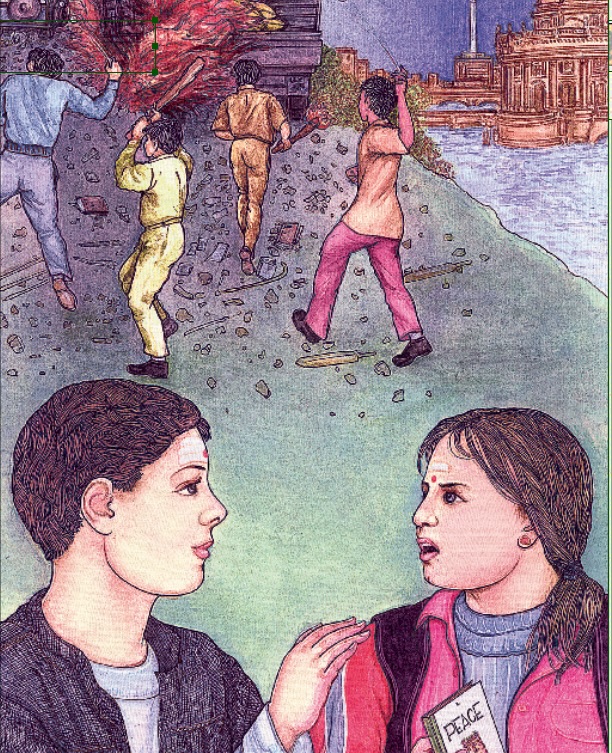

Attitudes of prejudice toward those of a different race, nation or religion can start simply as distrust, which can then deepen into dislike and deepen further into hatred, which can turn into a desire to inflict injury. Are we born with such attitudes? Certainly not. As children, we are taught them at home, at school and even in some religious institutions.

In the last few months a number of resolutions have been passed objecting to the US war with Iraq. Thousands of people have objected by demonstrating in the streets all over the world, including the US. These actions are sincere and make a point, but they certainly do not address the core of the problem, which is hatred.

People have been raised to hate those of different ethnic groups, faiths or countries. The solution, though admittedly a long-term one, is that we need, in the century ahead, to teach all children tolerance, openness to different ways of life, different beliefs, different customs of dress and language. We need to stop teaching them to fear those who are different from themselves, stop teaching them hatred for peoples of other colors and other religions, stop teaching them to see the world as a field of conflict, and instead instill in them an informed appreciation and a joyous reverence for the grand diversity we find around us. Instead of teaching children to be intolerant and to dislike and distrust, hate and inflict injury on those who are different, we can teach them to be tolerant, to like and trust, befriend and help. Of course, the central place to convey such a crucial message to the next generation is in the home. Secondarily, it can be strengthened in classes at the temple and school and through special community activities.

It is in the home that we can enduringly change the world for the better. It is the qualities we cultivate in our children that create the world of the future. Therefore, the most effective form of protest to the violence is to give more thought to what our children are learning as they grow up. In this regard, every father and mother is indeed a guru—in fact, a child’s first guru, teaching by example, explanation, giving advice and direction. The quality we wish parents to develop in the child is a prejudice-free consciousness—an open-mindedness that readily embraces differences in ethnic background, religion and nationality.

How can parents nurture a prejudice-free consciousness? Through complete avoidance of remarks that are racially or religiously prejudiced, and through discussing with children any prejudice they hear from others at school and elsewhere and correcting it. We—meaning we of all nations and cultures—can teach children to avoid generalizations about people and instead to think about specific individuals and the qualities they have. Even positive generalizations should be avoided, as they encourage us to not look at the qualities of specific individuals. When we say, even positively, that Chinese are good businessmen or Germans are efficient and precise, we promote stereotypes that blind us to the truth that all individuals are unique. TV and movies can provide useful situations to discuss with your children, not leaving the conclusions to their youthful minds. Tolerance can be developed by having our children meet, interact and learn to feel comfortable with children of other ethnicities and religious backgrounds.

There are a few key Hindu beliefs that are the basis for Hindu tolerance. The first belief is on the nature of God. Hinduism has a wide diversity of traditions, but followers of the different traditions respect one another and worship side-by-side in many temples. Hinduism has four major denominations. To Saivites the Supreme is Siva. Saktas refer to the Supreme as Sakti, Smartas call the Supreme Being Brahman, and to Vaishnavas He is Vishnu. However, the important point is that each Hindu is worshiping the same Supreme Being. The name is different, the tradition is different, but it is the same Supreme Being that is being worshiped by all Hindus. An ancient verse from the Rig Veda (1.164.46) is often quoted in this regard: Ekam sat viprah bahuda vadanti. “Truth is one, sages express it variously.”

Hindus also believe that there is no exclusive path, no one way for all. They profoundly know that the God they worship is the same Supreme Being in whom peoples of all faiths find solace and peace. Since the inner intent of all religions is to bind man back to God, Hindus honor the fact that “Truth is one, paths are many.” Ekam sat anekah panthah. Nonetheless, Hindus realize that all religions are not the same. Each has its unique beliefs, practices, goals and paths of attainment, and the doctrines of one often conflict with those of another. Even this should never be cause for religious tension or intolerance.

Another Hindu belief that gives rise to tolerance of differences in race and nationality is that all of mankind is essentially good, that we are all divine beings, souls created by God. Hindus do not accept the concept that some individuals are evil and others are good. The Upanishads tell us that each soul is emanated from God, as a spark from a fire, then begins a spiritual journey, which eventually leads back to God. All human beings are on this journey, whether they realize it or not. So when a Hindu sees a person whom others call bad or evil, he thinks to himself, “This is a young soul, acting in terrible ways, but one day, in the course of many lives, he will realize his errors and adhere to dharma.” The Hindu practice of greeting one another with “namaskara,” worshiping God within the other person, is a way this philosophical truth is practiced on a daily basis. Ayam atma Brahma, “The soul is God.”

This is taken one step further in the adage Vasudhaiva kutumbakam, “The whole world is one family.” Everyone is family oriented. Most of what we do is for the purpose of benefiting the members of our family. We want them to be happy, successful and religiously fulfilled. And when family is defined to be the whole world, it is clear that we wish everyone in the world to be happy, successful and religiously fulfilled. The Vedic affirmation that captures this sentiment is Sarve janah sukhino bhavantu, “May all people be happy.” Albert Einstein once observed, “A human being is a part of the whole, called by us Universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty” [H. Eves, Mathematical Circles Adieu, Boston, 1977].

Of course, this doesn’t mean we should teach children to gaze naively at everyone through rose-colored glasses, especially those who have been taught to hate others because of their particular race, religion or nationality. It means not looking at people through distortive lenses of malice, bigotry or bias. Hatred is a reality in this world and needs to be responded to realistically. While being aware of the prejudices of others and the philosophies they have been taught, we can still choose to see their Divinity and hold no prejudice—no ill-feeling or hatred—toward them.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Hindu concepts became more and more popular and influential in the West. Every year more Westerners take up the belief in karma and reincarnation as a logical explanation of what they observe in life. One of the most visible uses of Hindu values in the West in the 20th century was by Dr. Martin Luther King. After many years of thought, Dr. King selected the Hindu principle of ahimsa, as exemplified by Mahatma Gandhi’s tactic of nonviolent resistance, to overcome the unjust laws of racial discrimination in the US. In 1959 Dr. King spent five weeks in India discussing with Gandhi’s followers the Mahatma’s philosophy and techniques of nonviolence to deepen his understanding before putting them into use.

Perhaps in the 21st century the world can again turn to Hindu values, choosing this time the value of tolerance, raising children with a prejudice-free consciousness as a way of creating a future for this planet that is free from war and terrorism.

Teach your children, and show them by your example, that tolerance should not be mere passive acceptance of those who are different—an aloof tolerating—but rather a heartfelt empathy and proactive effort to befriend and help.