BY ANANTHA KRISHNAN

It’s the middle of December and the festival of music and dance that I have come to witness is just about to begin. One of the largest music celebrations of its kind in the world, it features a month of performances that take place all over the city.

Unlike the classical Hindustani music of North India, the Carnatic music of the South is more structured, lyrical, ornamental and strict. Due to these formalities, it offers less opportunity for improvisation but is more representative of time-honored tradition. “Carnatic music seeks more to enlighten than entertain because of its Vedic origin. This is an art for God’s sake and not for art’s sake, ” says one knowledgeable musician.

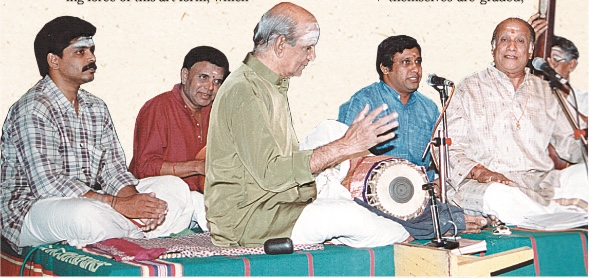

Lord Siva’s “original band ” is said to have consisted of celestial musicians playing mridangam (drum), tambura (drone), cymbals, vina (stringed instrument) and flute. Today, a traditional South Indian classical performance might feature these five instruments along with the ghatam (clay-pot) and the violin. In South India, music and dance have developed as an adjunct to worship. Devotion is the driving force of this art form, which is comprised of songs in Sanskrit as well as in all of the main southern languages: Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam. According to South Indian tradition, the purest form of teaching has always been the oral method, in which training is passed along personally from teacher to student. Because of this, many of the great South Indian compositions have been lost simply because they were never written down.

Bharata Natyam is the featured style of dance at the festival. It is the oldest of the four major dance traditions of India and the main classical dance of the South.

The Chennai Music Festival offers a rare opportunity for new artists to be discovered and for established performers to hold their ground in the hearts and minds of the festival’s dedicated attendees. Celebrated annually since 1927, this grand music extravaganza has always been organized and promoted by Chennai’s Music Academy, an educational institution that was formed one year after the first festival took place and is today the oldest and most respected music institution in South India. There are over 40 such schools in Chennai alone, and they all join the Academy in offering more than 1,000 music and dance performances during this festival month. The concerts themselves are graded, with juniors performing in the afternoons and seniors in the evenings. The afternoon slots are generally admission-free and not crowded, but the evening concerts are packed. That’s when the stars come out to shine.

Though violin has long been part of the South Indian classical ensemble, there has been a recent trend toward bringing in other Western musical instruments, such as the mandolin, guitar and saxophone–as well as a variety of keyboard instruments. Carnatic music is still the style of choice and the expectations for excellence have not diminished. While these new instruments are very popular, they are still considered a novelty.

The dancers are also experimenting. There are new dance categories with names like “dance-drama ” and “celluloid classics.” This last division features young high-steppers performing dance sequences from old Tamil film classics. One of a handful of overseas participants this year included a dance group from Singapore performing traditional Chinese dance.

Finally, there is one non-musical specialty of the festival that cannot be neglected. Distinguished and distinctive South Indian cuisine like dosai, vadai, pongal and uttappam can always be found in a variety of preparations at a number of Chennai’s famous eateries, casually referred to as “canteens.” I must say that these canteens are as much a crowd-pleaser as are the performers. Certainly they make as much or more money. When I asked one plump fellow what made him step into one of these establishments even during the high point of an excellent concert, he replied with gusto: “It is in the tradition, sir. A music-lover will have his snacks while visiting the festival during the music season. The music and the canteen go together.”

Canteen visits and instincts for socializing can make an audience forever mobile and audible in a concert hall during a performance. This can be somewhat disconcerting for those who are not used to it–especially connoisseurs from the West who are accustomed to a certain reserve in the art of music appreciation.

A young man named Gopu, sitting next to me, said, “This is the way a Carnatic music lover experiences a concert. It does not make him any less of a fan. Yet as these artists of today travel the world and get used to the quietly disciplined venues elsewhere, they are starting to demand similar behavior in Chennai halls as well.”

During this festival season, there are a number of bhajan groups out and about. These dedicated souls are not formally trained. They qualify for their music only through their heart-rending devotion. Yet they are unforgettable. Many a morning, I woke up to this joyful singing. Peering down from my hotel window, still in my pajamas, I regretted not being right down there on the dusty road to catch these joyful and carefree renditions belted out by bhaktars (worshippers) so fully immersed in the bhava (devotion) of their music they hardly noticed the sun rising.

Because the death anniversary of the great South Indian composer Thyagaraja coincides with the festival, many committed musicians now travel on pilgrimage to his burial place on the banks of the river Cauvery in the tiny hamlet of Thiruvaiyaru. These ardent souls can be heard singing the saint’s legendary compositions far into the night.

Even when the festival is over, Chennai residents are reluctant to let go of the party spirit. Certainly, at times like this it seems this ancient musical tradition will live forever. Yet as my taxi goes scarily winding and speeding toward the Chennai airport, I ponder the despondent thoughts expressed by one music lover who was concerned that the arts of South India were dying. Even as he was talking to me, I could not help but think: “Although some legends of music may appear to be lost, new genius is undoubtedly in the making, and great innovations are certainly on the horizon. Nothing great is ever lost.”

“I WAS THERE ”

One of South India’s most respected classical musicians, Sri S. Rajam, 87, has enjoyed long affiliation with Chennai’s famous annual music festivals. He is also a highly accomplished and uniquely creative graphics artist who has done many paintings for Hinduism Today. Below, the master reflects upon Chennai’s legendary legacy of music.

What were these festivals like in the beginning? My father took me to the very first one. I was only about ten years old at the time. In those days, the evening performances would begin around 4:30 in the afternoon. There was no electricity, just lanterns–and no mikes. No more than 150 people would attend a single performance. It was wonderful–all natural. From the start it was uniquely famous.

What was the original purpose of these music festivals? The Music Academy wanted to create an awareness of South Indian classical music in its purity. During those first presentations, there were demonstrations during the day and performances at night. Music scholars as well as dance and instrumental performers were featured.

How have the festivals changed through the years? In the beginning they were all rather academic. Education was the focus, and the scholarly musicologists were the main feature. These musicologists were very good teachers and produced the best of performers, but they were not performers themselves. After a while, an “Expert Committee ” was formed to bring in highly qualified performers. I worked in All India Radio as Music Supervisor from 1945 to 1979. When I turned 60, I had to retire. At that time, I was asked to join this Expert Committee. I accepted and have been a member ever since.

Are the festivals getting better with age? Now the Academy is experimenting with different instruments and different combinations of styles. In the beginning, these things were not done. A strict classical standard was maintained. These changes are good and signify progress, but there is also a strong desire these days for “show ” and the sale of tickets. With modern technology, the nature and character of the instrumental and the vocal music is being lost. Also, there used to be more gurukulams (stringent live-in training schools for young musicians). They helped maintain a standard. Now, these strict gurukulams have been replaced with more lenient public schools

Do you have any suggestions for raising the standards? The festival could be shortened and the performances could be lengthened. Also, in the old days, when a musician walked on stage, he did not come prepared. He would be asked by the audience on the spot to sing or play a certain song. Let this kind of confrontation be reinstituted. This would stem the growth of the mushrooms, and bring them up to a very high level. This would also inspire a love of learning.