BY TIRTHO BANERJEE

During a visit to Varanasi in 1996, Stanford University professor Ronald Barrett discovered a large leprosy treatment clinic run by a group of ascetics known as the Kina Ram Aghoris. Fascinated by their implementation of Aghora medicine in the treatment of leprosy and moved by the plight of young leprosy victims begging in the streets of Varanasi, Barrett started delving deeply into the study of the Aghori’s ancient medicinal practices and eventually began writing a book about it.

The traditions of the Aghoris can be traced back to the practices of the “mad ascetics ” of the Kapalika order who lived in the 14th century and followed “left-handed tantric practices ” such as living in cemeteries and drinking from human skulls. Because some of today’s adherents of this tradition are said to continue these practices, the word aghora, which literally means “nonterrifying, ” may evoke in the minds of some, a picture of intoxicated ascetics engaged in wild and ghoulish practices. Certainly, such a perception would be understandable, considering their undisputed history and the fact that a cohesive understanding of their tradition is difficult to find.

While Barrett does not refute this reputation of the Aghoris, he is quick to assert that the people he met from this tradition were a sedate and socially respected assembly of ascetics and householders who, despite a continuing presence of death in their symbolic culture, followed their religious disciplines through established channels of social service and healing. Barrett explains that, although their association with ghosts, death and cremation has earned them notoriety, their aim is to boldly confront their aversions–the greatest being death–that they might attain perfect fearlessness and become true Aghoris, for whom all things are “nonterrifying.”

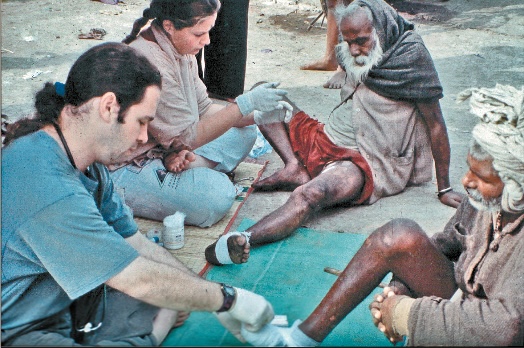

Barrett spent 22 months in India, primarily with the lepers of Varanasi that were being treated at the Krim Kund clinic in an ashram established in the 16th century by an renunciate named Baba Kina Ram. Barrett summarizes their healing system as consisting of an eclectic collection of practices ranging from modified ayurvedic and biomedical applications to more ceremonial practices such as a ritual called the “rites of self-cremation.”

He was also impressed by the fact that they not only focused upon the physical ravages of the disease, but also dealt with the resulting psychological damage suffered from severe social discrimination.

The Aghora medical adept attempts to heal or soothe his patients with the power he has accrued from his deliberate confrontation with death and disorder. Although he does this primarily through fire and water rituals, it is also the unreserved faith of his patients that forms an important part of their improvement or cure. The vibhuti (holy ash) of the ritual fire is applied to their foreheads, necks and afflicted areas. It is also ingested as prasadam (blessed food sacraments) and taken home by patients to be used in more rituals they perform themselves.

Barrett is careful to note that Aghora medicine is being practiced by professional doctors who volunteer their time at small ashram-based clinics where medicines are often concocted and modified according to the directions of modern-day Aghora specialists.

A variety of challenges plagued Barrett’s research in the beginning. Not knowing the local language was one of his biggest hurdles. Finally, he discovered that the personal experience of participation provided him with his greatest source of understanding. More than once he set aside his camera, notebook and pencil to join the activities he had previously only observed.

According to Barrett, the social stigma of leprosy is far more detrimental to the patient’s condition than any of the physical symptoms that result in infection. He also discovered that diseases with similar symptoms, like Leukoderma or vitiligo, elicited the same public disdain. In India, such social condemnation affects life in a fundamental way. These unfortunate souls are forced to endure continued threats of divorce, eviction, loss of jobs and ostracism from social networks, even long after they have been “cured.” To make matters worse, such extreme yet unspoken censure provokes concealment strategies among patients and their families, making immediate detection difficult and treatment less effective, increasing the possibility that the disease will result in incurable deformities and disabilities.

Barrett chose the perfect place for his study. While 67 percent of lepers worldwide live in India, 73 percent of those live in Varanasi. Certainly, he hopes his research will provide new insights in the field of medical anthropology. But more, he prays that–because of his involvement–a few more untouchables might be touched.