BY RASHMI SAHI

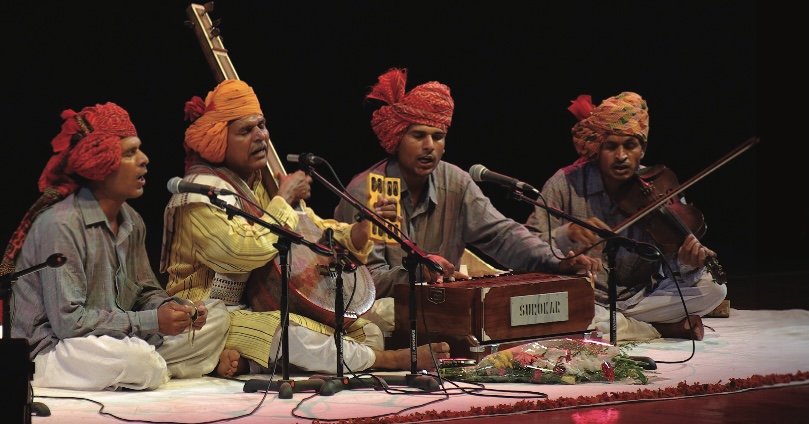

In Indore, Madhya Pradesh, the stage is set and the audience awaits. Center stage, a rustic-looking man dressed in kurta-pajama and a colorful turban is tuning his tambura (a five-stringed Indian musical instrument), immersed in his quest for perfection and oblivious to the chattering throngs. Finally satisfied with the strings, he alerts his fellow musicians with a glance. He plucks the strings of his tambura; the audience look up. The younger men join in on violin, harmonium and dholak (a two-headed South Indian drum). Slowly his voice rises over the accompaniment as he soulfully unleashes the ageless power of Kabir’s divine Hindi verses: “Sunta nahi dhun ki khabar/anahad ka baajaa baajta.” The multitude is transfixed.

Fortunately for English speakers, the famed poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) translated all of Kabir’s work into English (www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sok/ [http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sok/]). Tagore rendered this verse as: “Have you not heard the tune which the unstruck music is playing? In the midst of the chamber the harp of joy is gently and sweetly played; and where is the need of going without to hear it?”

Meet Padmashree Prahlad Singh Tipanya, the inspired bhajan singer who has dedicated himself to spreading the universal message of oneness given us by Kabirdas, the fifteenth-century poet-saint of North India.

Tipanya never expected to become an artist, much less an internationally respected folk singer. Employed as a government school teacher in a tiny, remote village in Madhya Pradesh, he was perfectly content with teaching science and math to his young students. But life had other plans for him.

One day in 1978, while visiting a neighboring village for the Purnima festival music gathering, he heard somebody playing tambura. Fascinated, he stayed back that evening to talk to the artist and expressed his desire to learn tambura. The artist immediately offered to teach him, advising him also to learn to sing. Overcoming his initial doubts about his voice, soon his nights were dedicated to the passion of learning tambura and singing. Joyfully he would cross the river to visit his teacher, two kilometers from his village. His mornings were free for mundane responsibilities, and he continued teaching in the village school.

In those days, playing the tambura was not considered a respectable profession, but nothing deterred Tipanya. He believed the tambura had a deeper meaning in Kabir’s teachings. Kabir said its beautiful sounds can be heard within oneself; he saw it as a symbol for something mystically profound, writing, “O friend! This body is His lyre.” In the same spirit, Tipanya declared, “Nothing can be accomplished without passion!”

Living and studying apart from his family, in a small room with his college-going brother, Tipanya made quick progress. Soon he was performing in nearby villages; his singing was well received. In his free time, he avidly analyzed Kabir’s teachings, while mindful of the poet’s stern rebuke, “Mindless reading of religious scriptures doesn’t help. Listen, gentlemen, this will only keep you stuck in the life-and-birth cycle.”

One verse in particular intrigued him: “Koi Sunta hai guru gyani gagan main, aawaz hoye jhina, jhina.” Tagore translates, “Is there any wise man who will listen to that solemn music which arises in the sky? For He, the Source of all music, makes all vessels full fraught and rests in fullness Himself. He who is in the body is ever athirst, for he pursues that which is in part; but ever there wells forth deeper and deeper the sound [aawaz] ‘He is this–this is He;’ fusing love and renunciation into one.” Purushottam Baba, a wisened musician, also engaged in the Kabir singing groups, encouraged Tipanya to find that sacred sound, “aawaz.”

A student of science, Tipanya was skeptical about anything not personally experienced. He took to meditating, and after long practice personally found that deep, inner sound that echos, “He is this–this is He.” Since that breakthrough, Tipanya has been undeterred on the path of Kabir; and he has inspired his two sons to follow in his footsteps. One son is a second vocal and plays manjira; the other plays dholak.

Pursuing this inner calling for three decades, Tipanya is now a familiar name in the oral tradition of Kabir in Central India’s Malwa region. His renown has also taken him abroad to the US, UK and other countries, where he has been warmly received by a wide variety of audiences. Search for “Prahlad Tipanya” on YouTube and you will find dozens of videos of his concerts.

The contribution of this modern bard has not gone unnoticed. In 2008, he received the Sangeet Natak Akademi award, and in 2011, the Padmashree, a prestigious honor bestowed by the Government of India, for his contribution to folk art.

Tipanya’s love of Kabir’s teachings has led him to collaborate with Dr. Linda Hess in the Kabir Project, started in 2003 by Shabnam Virmani to better understand and propagate Kabir’s simple but profound messages. Virmani was then artist-in-residence at the Shrishti School of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore; Hess is a professor of religious studies at Stanford University and a noted exponent of Kabir.

Fame has not jaded the humble villager. His renditions of Kabir’s songs are those of a pure soul and hence touch the inner being of the listener. In a personal interview, he made this appeal to one and all: “Kabir’s music is everyone’s music; it is universal. Kabir’s love is of devotion; and if we understand this very simple message of Kabir, then all the differences in the world will come to an end.” His plea echoed Kabir’s sentiments: “It is needless to ask of a saint the caste to which he belongs; for the priest, the warrior, the tradesman and all the thirty-six castes alike are seeking for God.” PIpi

Rashmi Sahi (rashmi.sahi _@_ gmail.com) is a Hong Kong-based Indian writer with a Ph.D in English literature. She loves books and culture.