Rajiv Malhotra’s new book is a tactical campaign to return the translation and interpretation of India’s spiritual literature back to devout Hindu hands

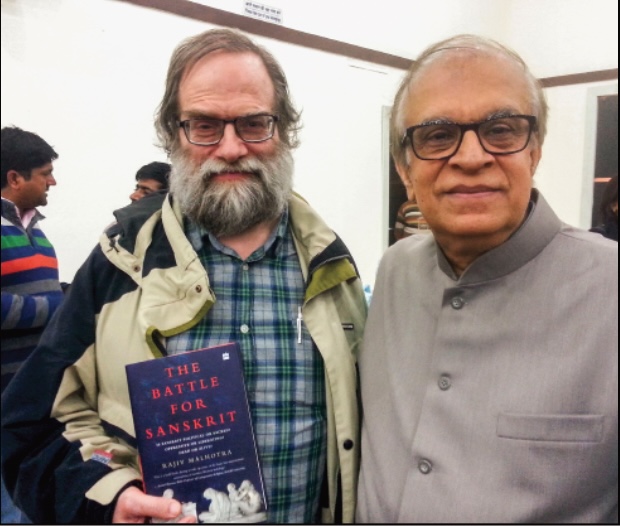

By Koenraad Elst

Rajiv malhotra’s latest book is not a work of Sanskrit scholarship. It deals not with grammar or literature, but with the politics of Sanskrit scholarship itself. The Battle for Sanskrit, Is Sanskrit Political or Sacred? Oppressive or Liberating? Dead or Alive? (TBFS, HarperCollins, Delhi 2016, 468 pp) reveals and examines mechanisms of knowledge production and intellectual control in the globalized post-modern world. In particular, the author documents the American attempt to wrest control over the Sanskrit tradition from the indigenous pandits, thus disempowering the backbone of Hindu tradition.

The Battlefield

Rajiv Malhotra, now living in Princeton, New Jersey, took early retirement at 44 from a very successful business career as a computer scientist working as a senior executive in the telecom industries. He then founded the Infinity Foundation to study the power equations underlying the way Western scholars construe India. He calls himself an intellectual kshatriya, a warrior who fights on the field of ideology to protect Hindu culture and our scriptures from the onslaught by the West. Though he is well-informed and productive in developing and documenting relevant concepts, Western academics and even Hindu nationalist detractors have lambasted him as not having the adhikara (prerogative) to criticize the academic world.

In the feudal age, one’s status trumped the humble consideration of whether one’s words were true. In the modern age things work differently. Albert Einstein was a mere clerk with no adhikara when he launched the revolutionary Relativity Theory. Closer to home, Shrikant Talageri was belittled as a mere bank clerk when he showed academics that the very readings and Vedic analyses on which they swore as evidence for an Aryan invasion from outside of india, did in fact logically proved that India itself was the homeland of the Indo-Europeans. Malhotra may not have academic status, but the thesis of his present book is essentially right, and it is a direct challenge to the academic India-watchers.

Malhotra observes that most Hindus are not aware that a war is raging for the destruction of their civilization. They don’t come out of their comfort zone, out of their career and family concerns, and hence have never developed a sense of the enormous hostility that is targeting them in the ugly wide world. Foreign experts in Arabic or Chinese tend to sympathize with the civilization or polity they study, and to defend it against prejudices and hostile stereotypes; but in South Asian Studies (the terms Indian and Hindu are taboo in those circles), the opposite is the case. When, like every immigrant group, US-based Hindus wish to correct the schoolbooks to make them less hostile and more accurate regarding Hindu history, South Asia scholars move in not to support but to thwart them.

In the face of this aggression by “experts,” Hindus think that since Sanatana Dharma has survived several onslaughts, it has nothing to fear from the present one. Here then is a meritorious role that Malhotra has increasingly played since he started his series of books: getting Hindus up from their cosy unconcern and into reality. In particular, he has taught them to scan the forces in the field and take an objective look at the hostile agents approaching Hindu society with flattering smiles and idealistic-sounding pretexts.

For the past, this job was done by the likes of late historian Sita Ram Goel. But very few people are equipped to map out the situation in the present, particularly the interaction between the academic world in the US and the intellectual sphere in India. The Americans’ agenda of national self-interest has joined with that of the Indian secularists, who use American universities as a staging ground for their anti-Hindu assault.

Under British rule the foreigners’ view of India had only limited consequences, though they did bequeath to India a Nehruvian elite. Today, the “deconstruction” of Hinduism by “experts” influences policies and socio-cultural evolutions inside India and gets broadcast into every Indian village. Indeed, even some Hindu leaders have come to intone destructive messages, such as “All religions say the same thing” (so don’t worry if your daughter converts to another faith) and “Yoga is not Hindu.” The Sringeri Math was about to entrust its traditions to the care of American Sanskritists, but Malhotra warned them, hopefully in time.

So, on one side of the battlefield is a sleep-walking Hindu society that doesn’t realize what’s happening. On the other is an ever-growing army of foreign scholars and India-watchers, allied with every divisive force inside India.

The Case of Professor Pollock

The knowledge production machine relating to Sanskrit—translations into English, commentaries, analyses, texts for university students and personal opinions of so-called experts that are adopted as truth by modern media, and then our own young Hindus—has moved from old school European indologists to a new breed of American scholars. In his book, Malhotra dives deep into the work of one such scholar, Sheldon Pollock—a professor at Columbia University. In a bizarre transfer of control over our literary heritage, Professor Pollock, not Hindu scholars, is now in charge of the translation and editing of hundreds of classical Sanskrit texts.

Why bizarre? Malhotra shows how Pollock’s approach to Sanskrit studies consistently undervalues the spiritual dimension that Hindus associate with this ancient tongue, portraying it as a language of oppression. Pollock’s motives deserve the benefit of the doubt; he has for instance deplored the decline of classical studies in India, and he is attempting to fill that void. But he reproduces the negative valuation of Hinduism, which Western India-watchers are spoon fed. Do we want that aversion for Hinduism to hold sway over the Sanskrit heritage? Malhotra observes that it “would hand over the authority of Sanskrit studies to Westernized scholars using [Pollock’s] political philology and not Sanskrit’s own literary theories or Indian socio-political resources. Persons who are outsiders to the Indian traditions would call the shots, and even become the proxies to represent the downtrodden” (p. 178).

Ever-more born Hindus are patronized by the likes of Pollock or Wendy Doniger. In a sad scenario, these second generation Hindus become part of the academic cabal that is attacking Hinduism. The author writes, “The effect of Pollock’s project on some Hindus is alienation from their roots and the development of an inferiority complex.…This alienation spreads quickly. Bright young Indians…rush to enter the university factories of this nexus and end up spreading the indoctrination to the public.” (p. 327)

Many Hindus are under the impression that scholarship, including translation, is an ideologically neutral job. In reality, translation comes with an interpretative framework that insinuates a number of anti-Hindu assumptions.

Reinterpeting the Ramayana

According to Malhotra, Pollock’s earlier works give us a clear indication of his position. He has openly declared that the Sanskrit language is dead. His treatment of Valmiki’s Ramayana displays a contrived politicized interpretation, which he terms “political philology.” Anything good in the book is, of course, the product of “borrowing from Buddhism” (in accord with the reigning assumption: “Hinduism bad, Buddhism good”). So he juggles the chronology to make the Buddha predate Valmiki. Malhotra writes, “Pollock’s over-arching motive is to make a chronology according to which all Hindu innovations came only after the Buddha, the idea being that prior to Buddhism the Hindus were incapable of innovation as a result of their oral tradition.… Rationality entered India only after the Buddha came, according to him, and only then did it become possible to compose complex rational texts.” (p. 390)

At heart, Pollock argues the epic to be evil—a trick by Brahmins and monarchs to justify royal power, priestly authority and caste apartheid. Moreover, he claims that, in justifying the war against Ravana, the Ramayana essentially declares war on all outsiders, particularly the Muslims—though these invaders would only arrive a thousand years later. So Pollock champions the Muslims along with the low-castes and Dravidians against Rama’s wicked aggression, thus to dislodge whatever remains of the oppressive Sanskrit tradition’s power and prestige.

In this now-dominant construct, Ravana is presented as a resister against Aryan aggression who is shown his place by the Aryan hegemon Rama.

The Way Forward

Malhotra concludes his book with a summary and a strategy. “Among the Western and Western-based indologists there are those leading an aggressive and well-organized movement to position the study of Sanskrit as a political battle ground. They claim it is infused with toxic elements supporting Vedic, brahminic and royal hegemony and that it encodes oppressive views of shudras, women, Muslims and all those who can be construed as ‘others.’ Most academic Sanskrit research is being taken over by two different vested interests: (a) social scientists and humanities scholars wanting to reinterpret India’s past and re-engineer its future by exhuming the toxicity they perceive in Hinduism; and (b) scientists, environmentalists, spiritual seekers, self-help experts and ‘new thought gurus’ intent on mining its treasure of knowledge.

“I am proposing what I call a ‘sacred philology,’ rooted in the conviction that Sanskrit cannot be divorced from its matrix in the Vedas and other sacred texts, or from its orientation towards the transcendent realm. It’s stance would be quite different from that of the Western, secular academy. Sacred philology involves first of all a respect for, and preferably a practice of, the sadhanas that have supported the dharmic traditions for centuries, including tapasya and meditation.”

Hindus Need to Study the Issues

Rajiv Malhotra has taken a powerful stand to ward off a clear and present danger and appeals to us all: “It is clear to me that many present-day Hindu leaders are ineffective in understanding and engaging the world of non-Hindus. We tend to either avoid the differences that arise or become defensive or, in a good many cases, tragically capitulate to the other side. What is needed is a dispassionate analysis of the other side that does not slip into any of these modes. We must look deeper if we are to understand the capacity (or lack thereof) of Hindus for intellectual engagement with groups that have a different world view.” Every Hindu who can contribute is called upon to do their purva paksha—read about and understand the issues. Then, join in the struggle.