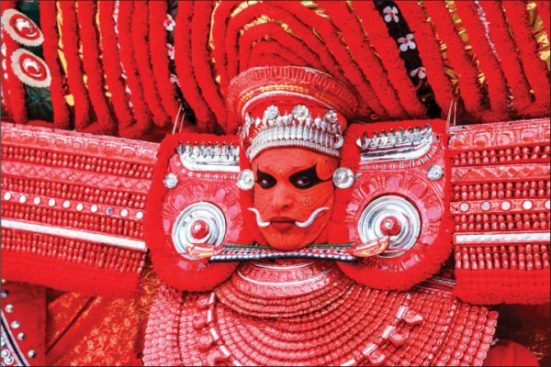

Kerala is home to an ancient dance form featuring deliriously elaborate costume design and choreography—all offered to God as a form of worship

BY NAINA LEPES

A THEYYAM PERFORMANCE EXUDES THE primordial sense of eternity ongoing. This dance-drama form of art and worship, loosely stylized in open nature, supports the open heart. The newly emerging historical stories brought from far and wide seem to merge and thrive with the telling and the listening, amidst the backdrop of breezes, chirps and swaying palms surrounding a tiny outdoor shrine with a lived-in house in the background. The performer is acknowledged as man-God combined, and the audience serves as natural participant, interacting as an intrinsic part of the whole through time and space. The audience even participates in viewing the dancers’ preparation of make-up and props, setting the tone for an extremely intimate and mutual experience.

Though some of the stories enacted may seem mundane, the natural setting, actors-dancers, makeup, drumming, music, chanting, props, masks and the holy ambience combine to create a fresh experience that can never be constricted by boxes, forms or words. This otherworldly magical vastness is the real beauty of my experience of Theyyam.

The overriding impact of Theyyam is presence, awareness, being. All else—the intricate make-up, body painting, grass skirts, headpieces finely tied with string, tall carved poles carried on the back, sparkling fire and smoky embers, action and inaction—all these are mere peripherals.

Whether it’s a trickster lord-death chasing children or a person-legend caked with body painting standing on a small wooden table holding up his insignia, eternal awareness is the only thing. This moves the heart and creates atmosphere, giving a sense of permanence to all the changes in life.

At first I thought I was attending a dance, so I wanted some dancing. But presence and stillness are far more lasting than movement. For this throws us back on our self: our ordinary person self, our self that is God.

In the beginning, when all the strings and headpieces and poles have been tied, the ritual costumes have been donned, the drums have sounded and the ancient Malayalam chanting has been intoned, now the hero is handed a mirror. He looks. And what does he see? He sees himself. He sees God. The character he is portraying is God. God is inside the character. God is inside his self, reflected back. Always present within the ritual, the movements, the stillness, the body. Always present as God.

Suddenly the ordinary person he once was becomes omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent. He knows exactly what is. And knows precisely what is needed for whom. So, at the end of the performance, when one approaches him for the blessing, he transmits what is given by God—not just the historical character he is portraying, but what is given by God. Is this “shamanism?” Forget the labels.

Although from the very beginning I attune with the indomitable presence, nonetheless I am turned off by the external noise and jumping, cameras clicking, people standing, blocking our view, and kids chasing. This is too busy, too much! The trickster senses my lack of acceptance. He stops running to offer me a banana, and just as I am about to accept with folded palms and bowed head, he snatches it away! This swift trickiness initiates reflection—accept all as equal: the ordinary, the extraordinary. All equal. And I leave with a feeling of ancientness—Africa? Hawaii? South Seas? Totem pole culture? All one before the land mass split.

For the next Theyyam I choose the theme—Vishnu Murthy. As he prances round the holy coconut grove to the sound of the drum, a speck of this all pervasiveness becomes known inside. Here no external circus. No kids chasing and cameras clicking that block the view. Sheer presence only.

Then an old man with big white lips walks to the beat of the drum. Slowly. Are the lips Neanderthal lips? This is Siva, the ancient one. Does he always accompany Vishnu without our knowledge? Of course! Prior to the human folly called Vaishnavite and Shaivite, these simple Dravidian artists understood the futility of division.

What we separate into holy and unholy—nonsense! The simplest boy within the proper lineage can embody Vishnu, who some think was once an ordinary human being himself and attained Godhood after the accusatory errors of a feudal lord became known; now portrayed by an ordinary person who realizes his Godhood within the sacredness of ritual.

The same is true with stories of the Goddess. Muchilottu Bhagavathi was once a Brahmin girl wrongly accused of improper conduct. She leaves her ancestral home and seeks refuge in a small shrine. After forty-one days, Siva appears, declaring her innocence. After the girl merges into a blaze of fire, auspicious signs reveal that she is a Goddess. Truth triumphs, the God-nature is revealed. What is so strikingly paradoxical about these stories is that even the one who commits the heinous sin of killing his Brahmin teacher can be recognized as God.

Where are the delineations? They are here only to foster the strength of the ritual itself. Conventional distinctions are considered worthless in a world where everything is equal. Then why the strict caste distinctions? Paradox seemingly abounds.

What feeds the Gods here? The naturalness of the land and its people—the nectar of naturalness! Every coconut grove in each plot of land has a tiny corner for a temple. And as the Gods live, they are believed in and their presence felt.

The land is pristine and the people generally kind. Many have not yet been bitten by the bug of touristic greed: natural, giving, happy. Two different rickshaw drivers refuse to accept money from me on a short trip to and from the Theyyam. “I want to help you,” they both say. The owner of a guest house down the beach refuses to accept money for lunch. “We have no restaurant. Lunch for guests only,” he says.

Squawk of baby hawk. A mother flies back and forth with straw to expand the nest. A tiny bright green bird almost camouflaged behind green cashew leaves, leaves its perch as a heavy fan branch thumps to the ground in the distance.

Waves swish back and forth while orb of sun shines through slits of palm. Green coconut clumps still up in spite of the many picked last week. Each morning I am awakened by haunting chants from temple and mosque within the backdrop of lilting ocean. Music from the ocean of life is always here in the background—if we can but listen.

Some people born here now live in Dubai, leaving all manner of native dwelling place behind, awaiting school vacation for the family reunion. So no overpopulation—yet.

Individual fishermen make their own industry with tire tube as boat. Their soft net collects fresh mussels and crabs. And coconut trees perpetuate the economy. Outside the veranda, an expert climber winds rope round his two feet, making them one. Effortlessly he slithers up the tree with sword in side pocket. From this distance, the curved sword resembles the tail of Hanuman. Another man on the ground is cutting off the outside brown shell from the older ones. White coconut meat inside is dried in the sun for six days, then pressed for oil.

The same climber appears day after day, tapping a spot high up for toddy. The local women participate, gathering up left-over dried coconuts from a deep pit dug ages ago. From this do they make coir for mattresses? Stray palm fronds are used to make fires. No waste here.

There’s a private beach cove next door, absolutely pristine till the sand smugglers come and leave a hole with some litter around. But even now the rest is beautiful and the hole can be overlooked—until the next batch of smugglers arrive. A few days later, the ocean has leveled out the sand and swept away all remnants of pollution.

I notice that the resort being built next door has been stealing sand daily for building. What to do? If I called the police, they won’t understand my English. Though the ocean might spew forth some sand every now and then, even beach sand is limited. The theft might one day backfire on the robbers, when their prospective guests have no beach on which to sunbathe.

Nearby volcanic rocks are alive, bestowing the feeling of sacred cathedral on those who venture near enough. The beach on the other side is interminable, beach after beach after beach. I walk only as far as the rocks, about five kilometers. On the way is a high cliff where you can sit under a palm, viewing sand and water stretching forever.

This is the only place I’ve ever been where there are no restaurants. Everyone eats at the homestay. Hindu and Muslim live side by side, friends intertwined within the Theyyam culture.

Some Theyyams you can walk to through jungle paths near backwaters as the ancestors did. Others must be approached by rickshaw. The drivers know which stories are being performed where. Timing can be anywhere from 4:30am to 1:00pm or later, or continuously, with varying stories in between.

Getting into character, from head to foot

Lest one get lost in ancient sacredness, let it be known that in a culture where one kills a guru and yet becomes God, there is no dark side to be suppressed as in the West. Here it just is.

The caretaker of the house where I am staying returns home inebriated at 11pm and starts screaming just as I’m dozing off to sleep. The next morning I ask him to be quiet when it’s late. He pretends to not understand, and says he was talking on the phone. I ask the landlady to explain to him, and he makes up a story about me which I won’t repeat.

It is said that sixty years ago, only brahmins were allowed to attend the Theyyam, and the other castes had their own Gods. I suspect that certain themes are needed only for brahmins: themes that evoke humility by ridiculing pride or rigidity or sense of superiority. Standards for brahmins are different than standards for other castes, as each group behavior is different, if samskara conditioning prevails. Obligatory duties or emotional expression vary among people with different kinds of mind, lifestyle and training. One level of psyche might need to develop a standard of right and wrong; whereas another might need to learn to let go of all standards and just be. These differing psyches should not be exposed to the same kind of training. Now the Theyyam is more mixed than sixty years ago. But still, tradition dictates that only certain groups are allowed to perform certain themes.

Global economics forces the entrance of Siva to homogenize existence, beating down old cultures unto the ash of destruction. Siva always accompanies Vishnu.

Therefore, do not let your heart cling to this glorious ancient Dravidian culture that might soon be destroyed by airports and concrete high-rise buildings. How else can the greedy psyche eventually help the vibrations of planet and cosmos but by destroying the status quo? With the destruction of culture comes suffering, with suffering comes seeking, with seeking comes an individual connection with the totality—minus all forms of group intermediary, be they strict or permissive. India I love because of her diversity. The “melting pot” mentality of the US is dull and lifeless! And the whole world is heading for just that! Unless another dimension, an eternal “new-now” consciousness pulls us out!

The area here in northern Kerala is now filled with palm trees all pervasive. Simple people go out into the sea with tire and net to fish for mussels and crabs. Nourishment is available and free. The clear waters swooshing back and forth comprise the background music of life. To me, this place can be called paradise!

Just seven kilometers away in the city, the land is filled with dull concrete apartment houses and occasional smells of rotten fish. Kerala’s fourth International Airport opened in December of 2018. Will these simple glorious homestays that allow ancient culture to shine also become concrete jungle devoid of palms? And what will happen to the minds of the people?

Global greed, travel agents, taxes for the government and bribes come when they pack all the tourists into concrete-slab hotels pumped up by air conditioners that consume electricity from polluting landslide-causing dams in the north, which upset the ecological balance in the region. The more global jets, the more dollars, the more Euros, the more rupees!

For now, enjoy. And be grateful you are experiencing a culture that is worthy of being called “culture,” as opposed to “society”—a culture that contains the seeds for engendering enhanced consciousness in those who are able to receive.

One morning early, I walk to a small home nearby that serves appam for breakfast. On the way, behind the sprawling cement houses under construction, I see a small cottage with traditional roof, almost hidden by palms. On returning home, a thin woman with black headscarf on the roadside near the gate is gathering palm fronds. From the distance our eyes meet. She is wearing large round earrings. Her dress is unusual, her appearance otherworldly. While staring, I point to my earlobes, acknowledging her earrings in admiration. And we two smile.

There are over 400 forms of Theyyam

“Theyyam is an 800-year-old celebration of divinity and devotion in the northern Malabar region of Kerala, a mélange of dance, drama, music and mime. The musical dance performance is ritualistically held at some 1,200 temples throughout Malabar. Each participant represents a heroic character with divine power. It is believed that the mortal bodies of performers become one with immortal spirits and mythical figures to perform ritual dances and cast a trance over onlookers. The performance ends with distribution of turmeric powder as a token of blessing to the devotees. In return, they sprinkle rice grains over the performers.“

By Sourav Agarwal