By Lavina Melwani

At a big society wedding in Delhi, everyone was dressed in the latest budget-busting designer outfits, yet all eyes were on a young girl dressed in a rich, bluish pink Banaras sari with intricate floral motifs. This one-of-a-kind sari had cost her nothing, for it had been part of her mother’s trousseau thirty years ago. Instead of getting stale and out of style with age, the sari was the cynosure of all eyes, a treasure which had grown more valuable with time.

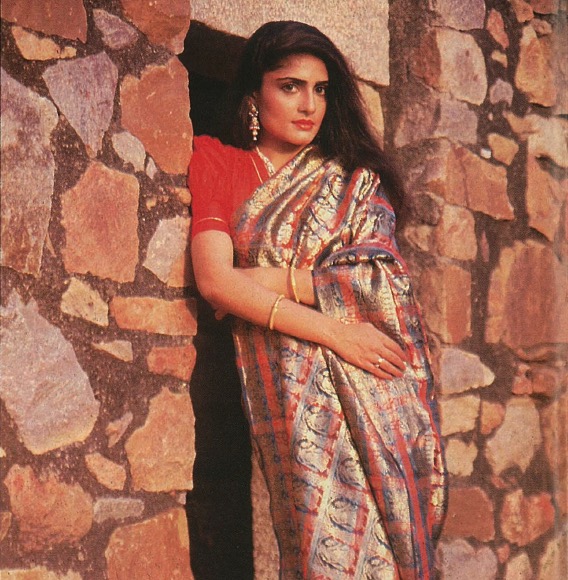

Who would have thought that six yards of fabric could be a synonym for elegance, beauty and style? The sari is the world’s longest-running fashion story, as relevant today as it was hundreds of years ago. While the sari shares space in a modern woman’s wardrobe with the very popular salwar kameez (also known as the Punjabi suit, consisting of trousers and a long top) and Western pants, it is still very much around and the garment of choice for many, be it a washerwoman, an urban working woman or a high society socialite.

While Western dress has made inroads into almost every Asian culture, with traditional garments like the Japanese kimonos and Chinese cheong-sams being reserved for ceremonial wear, the sari is a living garment, a part of the daily lives of women in the Indian sub-continent, from Nepal to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Practical and always in style, it is a forgiving garment which conceals a woman’s imperfections and enhances her special qualities. Even today for a young girl, draping a sari for the first time is the ultimate coming-of-age experience.

While the sari lives on in villages and cities, young innovative designers in India now give it fresh life and a new twist for the new generation. In India there are about 15 established labels such as Rohit Bal, J.J. Valaya, Rina Dhaka, Suneet Varma, Tarun Tahiliani, Sandip Khosla and Ritu Kumar. These designers have revitalized the sari, adding heavily embroidered blouses to plain saris, or re-styling the pallav (the portion of the sari which covers the bodice and falls over the shoulder) to give a new look to the sari. There’s even been the zip-on sari for girls who may have trouble handling all those pleats! At fancy weddings many women drape the sari in Gujarati style or seeda (straight) pallav (the pallav is taken from the back to front instead of being taken from front to back)–considered high style by the fashion-conscious.

India’s designers, adroit in Western styles and fashion, still take great pride in ethnic traditions, and their offerings often echo embroideries and designs of earlier craftsmen, celebrating India’s cultural heritage. There are designer saris which have scenes from the Mahabharata or Ramayana embroidered on the pallav, or the border of the sari, or entire village scenes in kantha work (running stitch embroidery used to make elaborately decorated quilts) from Bengal. There is a kind of visual poetry in these saris, often woven by Muslim artisans for Hindu brides. Some of the best embroiderers in India are Muslim, who can even reproduce the intricate pieta dura work found on the Taj Mahal. Saris tell stories–of the Ramayana, of folk lore and mythical heroes and verses from the Vedas. Ganesha–the auspicious one–is popular on sari pallavs.

As Indians have spread around the world, they have taken the sari with them. Saris are a common sight in London, Johannesburg, Trinidad, Toronto, Hong Kong and Singapore. In places as far apart as the Middle East and Lagos, saris are a part of the landscape. In fact, saris are big business in countries like Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan which produce bolts of synthetics like chiffon, satin and nylon which are bought in sixyard lengths by Indians as saris. These are exported to many countries and find their way to the Little Indias in the US, UK and Dubai.

The American way: Sari stores thrive in many Indian enclaves in America. Among the largest is India Sari Palace in New York, with a vast inventory from India as well as Japan. March was their annual 50 percent sale–a big event for US sari wearers–and the harried salespeople could hardly answer this reporter’s questions, so inundated were they with shoppers. Many communities, such as the Gujarati, wear mostly saris, and so there is a constant demand even in America. Just looking at the stores in Little Indias across America indicates the sari is thriving. In the 60s, many women were reluctant to wear saris in the US, afraid they would stand out. But in multicultural America in the 90s there seems to be a new pride in one’s roots. While women working in corporate America may still prefer to wear Western dress to fit in, others in less structured jobs–film editors, writers, travel agents–often wear salwar kameez or saris to work.

Women in America especially wear saris to evening events. After all, there is nothing quite as graceful as the sari, especially for evening wear. While styles and lengths of the salwar kameez fluctuate with alarming regularity, a sari is always in style. Traditional saris from different regions each have a beauty all their own and are timeless.

Kavita Lund, a wife, mother and accountant who lives in New York, has a sizable collection of saris and enjoys the grace it imparts. She, like most of her friends, wears the more practical pants and salwar kameezes during the day and saves the saris for special occasions and evening events. Her 19-year-old daughter, Monisha, born and brought up here, is just as fascinated by saris, although she wears only the trendy designer styles. These modern incarnations of the sari would probably make any great-grandmother faint–the stomach is completely exposed and the sari pallav is wrapped nonchalantly around the neck, leaving the bodice bare. Dr. Manjula Bansal, a pathologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery and the Cornell University Medical Center in New York, has a large collection of saris from every part of India and wears them with great pride. Even when she was a medical resident, she would wear a bindi on her forehead and saris to her workplace, riding on the subway. Now she wears salwar kameez to work, since this outfit is more practical, but always dresses in saris to social events, be it an Indian or a mainstream gathering.

Bansal, who was involved with funding of the India Chair at Columbia University and with other mainstream cultural organizations, finds her sari a great ice-breaker at international gatherings. Her authentic saris from many regions of India are always great for conversation and make her many friends. She says, “Not only is a sari beautiful, but it is a story in fabric, depicting religious and social beliefs and shows good omens for a good life. Every craftsman puts his identity into it. You don’t have to be beautiful to feel beautiful in a sari. It brings out your inner beauty and grace.”

So many styles: As in all countries, Indian dress usually indicates religion, social position, ethnicity, wealth and regional origin. Saris are no exception. While this is still mostly true in India, some urban Indian women and those living abroad do wear a cross-section of saris from different regions, and are certainly more Indian than regional in their perspectives.

Women have a rich array of saris to choose from, including handloom saris from Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, silk brocades from Varanasi and Kanchipuram, jamdani (fine, transparent cotton muslin) from West Bengal, cotton saris from Kota in Rajasthan, patolas (elaborate, five-color design) and ikat (special dye process) from Gujarat, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. For those living abroad, a trip to India means a new wardrobe, since the variety of fabrics in Indian cities is so vast.

Interestingly enough, just as there are fakes in art and jewelry, there are fakes in saris. Today it’s easy to be taken for a ride because technology has improved so much that saris with artificial gold look identical to those with real gold threads, the difference in price being a hefty Rs.10,000 at least.

Advances in India’s technology have made saris more affordable and easy to maintain for working women. Synthetic saris made in powerful industrial mills are attractively priced and don’t need heavy ironing or care. The flip side is that this has endangered the livelihood of village craftspeople who can take many months on a loom to produce a sari. As one old weaver told Bansal when she visited him in his dilapidated, almost shut-down workshop, “People are impatient nowadays, and they can get ten machine-made saris for the price of one hand-woven sari. They don’t want to wait or spend the money.”

Fads and experiments: Recently the New York Fashion Institute of Technology showed the saris of Princess Nilofer. Nilofer, an Ottoman princess who married the son of the Nizam of Hyderabad, made the traditional sari her own by giving it a Western touch through decoration and the placement of motifs. Her saris were ornamented with sequins, beads and metallic embroidery on chiffon, crepe and net, with the floral designs falling in the front or over the left shoulder. These saris were designed by a Frenchman, Fenande Cecire, and embroidered in India. In fact, in the days of the British Raj the Indian princesses traveled to Paris and often got their saris designed by French couturiers. Recently some of these saris came up for auction.

Saris, with their golden threads, intricate embroidery and innate romance have always attracted Westerners. Glimmerings of India inspiration appeared in the 1920’s when Madame Gres, a renowned Paris designer, showed sari-inspired styles in her collection. Western passion for Indian fashions can be traced to the British Raj when socialites in London, New York and Paris were smitten by Indian fabrics and embroidery. Famous Western designers were very influenced. Those who’ve used saris and Indian fabrics in their collections include Mary McFadden, Oscar de la Renta, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Norma Kamali and Anna Sui.

Recently, British designer Paul Smith did an entire collection based on India, including men’s shirts created out of saris. When Indian designer Rohit Bal’s mother saw this collection, she said plaintively to her son, “What’s all this nonsense about? I used to make shirts like this for you when you were young, and you never wore them!” To which Bal retorted, “I’m sorry, mom, but that was you. This is Paul Smith!”

While some Westerners fashion saris into everything from pillow covers to tablecloths to evening dresses, others actually wear them, a momento of their Indian adventure. Some designers use it to outrageous effect: John Galliano was once spotted at a society gala in New York wearing a silk sari with his short tuxedo jacket and dress shoes. Supermodel Naomi Campbell wore a sari at the MTV Music Awards, and Goldie Hawn, a great fan of India, often wears saris to social events. The Duchess of York was presented with a green Benarsi silk sari by Prince Andrew in happier days. Legendary ceramist Beatrice Wood, who recently died at 105, wore nothing but saris and Indian jewelry for the last several decades of her life. And pop icon Madonna is very much into Indian saris, mehndi and meditation in her latest CD, “Ray of Light.”

For mainstream Americans, the sari is still an exotic garment, a costume to transport them to another world. In fact, Magic Markers Costumes, a Halloween costume supply house in Huntington, West Virginia, offers a sari for rental, along with blouse and petticoat, for US$40. Their website: www.magicmakers.com, shows an American woman draped in a sari.

Fads come and go, but the sari survives them all. As Bansal points out, “One wants to be noticed, especially in a crowd, but why ape the West? The sari creates an instant identity for you, and I think that’s what most people are looking for, whether you are a CEO or a physician or you’re trying to make a mark. The sari says a lot about you.”

NEW DELHI SARI STORES: MEENA BAZAAR, E-19 NEW DELHI SOUTH EXTN., NEW DELHI 110 049 INDIA, OR 5/54 AJMAL KHAN RD, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI 110 005 INDIA, E-MAIL: SE@MEENABAZAR.COM, WEBSITE: WWW.MEENABAZAR.COM; KALPANA, F-5 CONNAUGHT PLACE, NEW DELHI 110 001, INDIA, E-MAIL: CULTURES@NDA.VSNL.NET.IN

TOP TEN SELLING SARIS IN INDIA

This list was garnered by Hinduism Today correspondent Rajiv Malik from New Delhi’s Mr. Vishnu Manglani, a leader in India’s national sari business. Prices given are in US dollars.

1Gadwals: Cotton with separately woven and attached silk borders and pallavs. Made in Andhra Pradesh. $25?130.

2Tanchois: Pure silk with intricately woven pallavs and borders. Variety of designs used. Made in Varanasi. $130?400.

3Bumkais: Silk yarn, made in Orissa. Yarn is dyed so that, when woven, patterns appear in various colors. $20?125.

4South Handlooms: Like Kanjivarams, but cost less. Bangalore made. Jari and silk borders and pallavs. $90?300.

5Printed: Silk, hand printed on three materials: silk, crepe and chiffon. Comfortable for party or home wear $65?130.

6Tangails: Fine cotton, hand-woven in Calcutta. Traditional Bengali designs. It gets softer with each washing. $10?100.

7Cotton Handlooms: Hand-woven in Coimbatore. Elegant for summer wear. Rich and crisp. Need much care. $20?50.

8Valkalams: Pure silk, woven in Varanasi to depict folk art scenes. Special handlooms can weave 25 colors. $90?400.

9Kanjivarams: Finest handloom silk, specialty of Tamil Nadu. Also called heirlooms. Pure jari-woven borders. $130?1500.

10 Chanderis: Made with silk and cotton yarn in Madhya Pradesh. Saris are lightweight, ideal for summer. $20?125.

MEN’S FASHION

UNFITTING GARB

IS THE DHOTI DYING?

This month’s feature stories hail the fact that most Hindu women, to this day, maintain traditional dress and are proud of it–an ancient legacy standing tall above masses of world fashions that have come and gone. Sadly, it is not the same with men’s apparel.

Ananda Coomaraswami, the Anglo-Sri Lankan art critic and philosopher, returned from England to Sri Lanka at age 25. He was horrified upon seeing mens’ “vulgar imitation” of the West. In 1905 he published the book Borrowed Plumes, describing adoption of European dress as “destruction of national character, individuality and art.” He set aside his own pants and suits and adopted a dhoti (waist-cloth) kurta (Indian-style long shirt) and turban–ironically imitating the natives he had been urging not to imitate his English brothers. His campaign failed, as any subsequent visitor to Lanka can testify.

Similarly, during India’s struggle for independence from Britain, Mahatma Gandhi changed from a lawyerly South African suit to a dhoti, urging others to “follow suit.” He generally failed too–today most Indian men wear borrowed plumes. But he was successful in keeping the indigenous textiles industry in India alive and competitive with British fabrics. On an optimistic note, the dhoti recently appeared in a Paris fashion show. It is a glimmer of hope for renewed use among Hindus themselves.