A richly illustrated glimpse into the spiritual journey made by a million devotees each year to one of the world’s most iconic celebrations of Lord Murugan

BY ALEXANDRA RADU, KUALA LUMPUR

THE WORSHIP OF LORD MURUGAN, GOD of war and victory, has dual origins, both in Tamil folk traditions and the northern Sanskritic traditions. Over time the worship of Skanda/Murugan developed with incredible complexity, reaching millions of worshipers in South India from all social backgrounds.

Like other festivals honoring Lord Murugan, Thaipusam is celebrated not only in India and Sri Lanka but also in the Hindu diaspora—in Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritius, South Africa, Fiji and other Hindu Tamil communities. Each of these communities evolved in unique sociopolitical contexts, so their cultures are varied, but common elements are found in Murugan festivals worldwide.

Many of India’s major Murugan pilgrimage sites are linked to episodes from His legendary quest. The temple at Palani, long associated with systems of healing, is where Murugan is believed to have defeated the asura Idumban, conquered His inner passions and realized the Truth within. Several festivals, major and minor, are held there annually; Panguni Uttiram and Thaipusam attract hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. Tiruchendur, a major Murugan temple located on the seashore in the Tirunelveli District in the Bay of Bengal, is the mythical site of Murugan’s final battle with Surapadman. There the kavadi worship occurs at the festival of Chittrai Paruvum, held during the Tamil month of Chittrai (April-May). At Thiruparankundram, near Madurai, where Murugan is believed to have married Devvayanai, the Vaikasi Vishakam festival is held in the Tamil month of Vaikasi (May-June).

Malaysia’s Hindu traditions and rituals have been greatly influenced by the waves of Indian migration which occurred during and after the British colonization of the area. In these newly formed communities Hinduism evolved in the absence of two key forces which played major roles in shaping Hinduism in South India: the prominent centers of religious learning and an influential brahmin caste.

Instead, the Agamic culture was brought to Malaysia by the Chettiar and Jaffna Tamil communities, who constructed major temples in the main cities of British Malaya. At the same time, popular village Hinduism was brought by those who arrived as indentured workers, and whose personal and community practices differed according to their place of origin. In the many plantation temples and roadside shrines, as well in most of the major temples, Lord Murugan, in His multiple forms, was a strong presence. With this widespread worship of Murugan, the Thaipusam festival has grown to become one of the most important yearly Hindu holy days in Malaysia.

Murugan’s Hilltop Abode

Built in the heart of a great limestone cavern cut into a hill in the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur, the Batu Caves temple complex is a unique sight, while, in a way, resembling Murugan’s pilgrimage sites in South India. Wilderness rules the area; monkeys and birds populate the steep walls enclosing the majestic caverns.

In 1891, K. Thambasamy, leader of the Kuala Lumpur Hindu community, was inspired by the Vel shape of the entrance to Batu Caves. He established a shrine for Lord Murugan within the main chamber, and placed a Vel—the spear-like symbol of Murugan—within it, prompting other Hindus to visit the site and offer worship. The British District Officer in Kuala Lumpur initially banned the worship, but his orders were successfully contested in court. This victory over the colonial authorities was regarded by many devotees as a sign of Murugan’s presence in the cave. The following year, in 1892, Thaipusam was celebrated there for the first time.

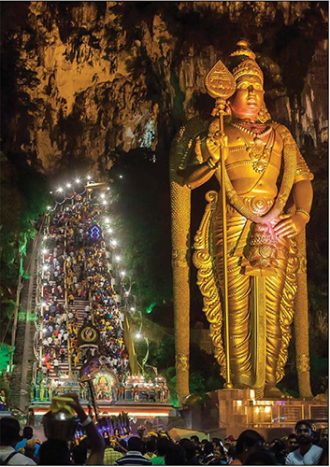

Over time, the modest shrine became a major pilgrimage site, transformed into a grand temple complex complete with a museum and commercial spaces. A central stairway with 272 steps leads up to the Temple Cave. Towering beside the stairway stands a majestic, 140-foot-tall statue of Murugan, the largest in the world.

While religious life at Batu Caves is continuous, with daily prayers and a steady stream of devotees and visitors, Thaipusam is indisputably the dominant festival of the year, annually drawing around one million people.

For this special event, Lord Murugan’s power center is moved from His main temple—Sri Maha Mariamman in central Kuala Lumpur—to this iconic Batu Caves outpost. The God is conveyed in a silver chariot with His two consorts, Valli and Devayani, attended by priests and followed by officials, musicians and thousands of Hindus from all social backgrounds. For the 2018 Thaipusam, a golden chariot was added to the procession, transporting the murti of Lord Vinayaga (Ganesha), Murugan’s sibling, who also has a temple at Batu Caves. The chariot was built specially for the Vinayaga Chaturthi festival last year at a cost of RM5 million (US1.27 million). “The golden chariot will be taken in the procession to enable the Hindu community in the city to see it, because public donations were received to make it,” declared Tan Sri R. Nadarajah, chairman of Sri Maha Mariamman Temple.

During the 18-hour journey from the center of Kuala Lumpur to Batu Caves, the procession stops at several Hindu temples, where offerings are made to the two Gods. Once at Batu Caves, the murtis of Murugan and His consorts are installed at the Sri Subramaniam Temple, while the holy Vel is transported up to the shrine in the main cave. As the God is installed in His lofty abode, the temple flag is raised and Thaipusam officially begins. For the next 24 hours, devotees arrive in droves to carry kavadi, fulfilling vows to beseach the blessings of Murugan.

Kavadi bearing at Thaipusam

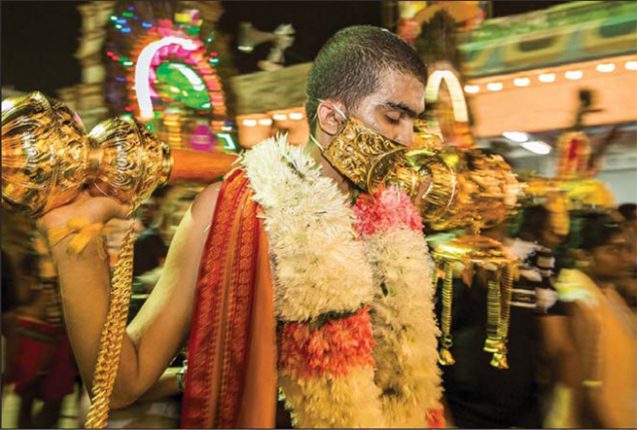

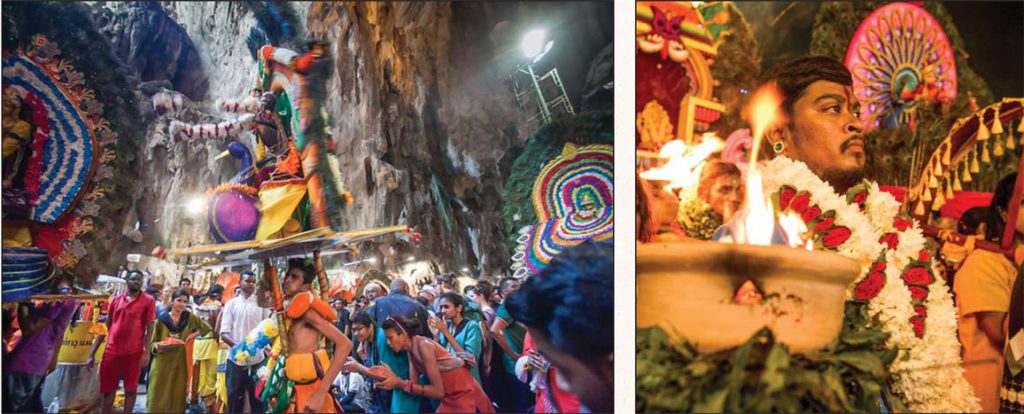

The power and presence of Murugan at Batu Caves can be felt throughout the three-day event. Thousands of devotees bear various types of kavadi to the main shrine inside the caves. Participants are often overtaken by trance, a divine state known as arul vaku (trance of grace), as the energies of the Deity flow through them. Entranced penitents appear to have transcendent powers, enabling them to pierce their flesh with hooks, spears and vels without feeling pain, and many without bleeding. The experience of the pilgrimage and the encounter of the God is shared with family and friends.

Kavadi worship at Thaipusam is rooted in Murugan’s legendary renunciation as Lord Dandayudhapani, and in the story of Idumban, who is transformed by his encounter with Lord Murugan while the former was carrying two hills from the north to the South of India. Kavadi is a popular form of worship in South India, especially in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and the Malaysian kavadi traditions closely resemble those of India.

Many devotees carry kavadi as a vow several years in a row or periodically throughout their lives, appealing to the divine power of Lord Murugan for help in solving personal or family problems. Blessings sought for good health, prosperity, success in occupation, studies, having a baby or resolving family conflicts. Often devotees start to bear offerings for Lord Murugan from their teenage years—in the beginning to fulfill specific vows, but over the years as an integral part of their spiritual practice.

Puravindra, a trade business owner, has carried kavadi for the last 12 years. “I have been devoted to Lord Murugan since I was a child. I was fascinated by the unique way devotees show their love for Lord Murugan, especially on Thaipusam. It started as a vow for studies at the age of 16, the first time I carried a kavadi. Over the years, I have been carrying many different types of kavadi, including piercings on the body. The earlier vows were for specific wishes, then it went on to evolve into pure love and devotion towards Lord Murugan.”

Pilgrims begin preparing for their journey a few weeks before Thaipusam, going on a fast and generally disconnecting from everyday life, seeking inner peace and balance in preparation for their pilgrimage. Murali, who has participated in the pilgrimage with his family since childhood, tells me: “I do fasting for 48 days, taking one vegetarian meal per day. The fasting also includes doing no harm to any living thing. Daily prayers are a key component during this time. I believe fasting helps us concentrate on our objective, which is to carry the kavadi successfully at the end of the fasting period. In my case, my family, initially my mother and now my wife, fast along with me.”

These weeks of fasting, in which devotees have endured privations, purified and balanced their inner selves, have prepared them for their encounter with the Divine. Accompanied by family and friends, kavadi bearers take a padayatra (pilgrimage by foot) of several kilometers, to the banks of a nearby river and up the 272 steps to the altar in the main cavern, bearing offerings to Lord Murugan, thus fulfilling personal vows.

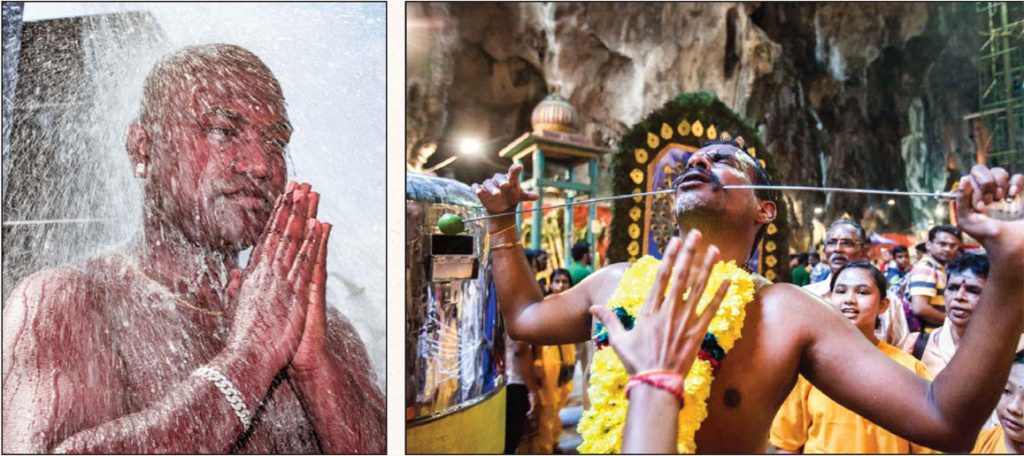

Upon arriving at the Batu Caves, the pilgrims hold final preparation rituals on the riverbank. They have their head shaved and take a purifying bath. “We do puja before carrying the kavadi. In this ritual we offer food and fruits, and pray to the kavadi itself before carrying it,” explains Puravindra.

Then, guided by their spiritual mentors, votaries often enter a trance, in which Lord Murugan connects with them, lending vigor to help them fulfill their penance. Once the trance is established, vels or hooks are inserted in the skin of the devotee. Finally, the kavadi is fitted and the devotees depart amid the singing of bhajans.

On their way to the shrine inside the main cave, pilgrims often stop to perform the kavadi attam, a dance mimicking the swaying movements of Idumban, who mythically carried the Sivagiri and Sakthigiri hills to South India as his kavadi. The energetic movements of the dance to bhajan rhythms, the bearing of kavadi that can weigh up to 200 pounds, and the wearing of vels and hooks through the skin all reinforce the feeling that the devotees are in a direct connection to Murugan.

On their journey, the votaries are closely followed and guided. “It’s not possible to complete this pilgrimage without the support of close family and friends. The very first part is learning from them about the strict rules of fasting prior to the pilgrimage, the dos and don’ts. They participate in the prayers held at home prior to the pilgrimage. Most of my friends and family also observe a vegetarian diet, keeping them feeling pure. To them, my journey is their journey, too. I’m blessed to play a small role in bringing my family and friends closer to Lord Muruga,” explains Puravindra.

As devotees reach the cave shrine, their offerings are delivered to Lord Murugan. The ritual milk pots carried by devotees are poured over the Deity. Fruits and flowers are also offered. Each devotee is released from their trance by a temple priest who applies holy ash on the forehead of the votary while chanting mantras.

Emerging from their trance, devotees suddenly realize how exhausted they are from bearing the kavadi. Some devotees actually collapse and are slowly brought to a normal state by loved ones.

While the pilgrimage at Thaipusam impacts the devotees physically and psychologically, for many the effects are long lasting and deeply impactful to the spiritual shaping of their lives. Murali narrates from his life: “I started at age 12, and for the last 32 years I have carried different types of kavadi. I began with the paal kudam (milk-pot) kavadi. Then I had a peacock kavadi. Then for years I carried small paal kudams on hooks on my back while wearing nail shoes. Finally, I decided it was time for Idumban kavadi, as my age is catching up with me, and I would like to continue this practice for the rest of my life. My parents and my family have always been my strongest motivation in carrying kavadi, along with the blessings of Lord Muruga.”

Conclusion

Murugan’s annual visit to Batu Caves on Thaipusam is a period of high spiritual energy which infuses the temple, caves and surroundings with His grace. People from all social strata undertake the pilgrimage, put themselves in the hands of a greater power and in the process succeed in conquering their ego, anger, lust, greed or hatred. The entire Malaysian Hindu community is brought together in honoring Lord Murugan.

.