Five duties, called pancha kriya, form the traditional minimal practices expected of every Hindu: upasana (worship); utsava (holy days); dharma (virtuous living); tirthayatra (pilgrimage); and samskara (rites of passage). Thus, most Hindus proceed on pilgrimage from time to time, choosing from among the seven sacred rivers or seven liberation-giving cities, the twelve Siva mandirs or the vast temple complexes of Mathura and Vrindavana, or thousands more holy places of India. Some visit the hallowed sanctuaries of Sri Lanka, Bali, Nepal and Bangladesh, Southeast Asia or the modern temples of Europe, America and Australia. How we follow the pilgrims’ way is more important than where we go.

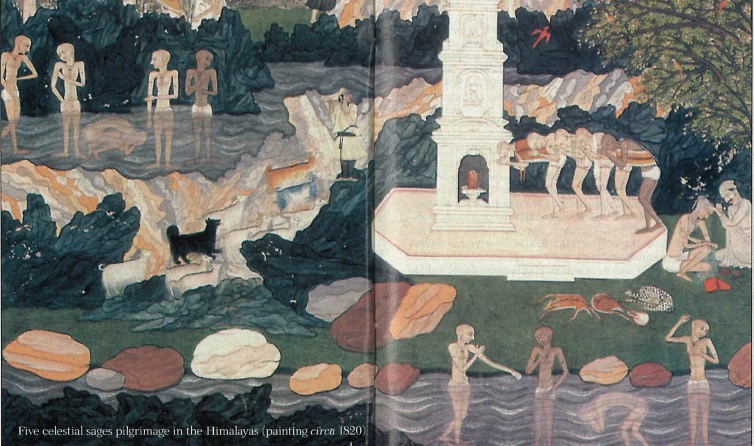

The concept of darshana is inextricably woven into tirthayatra (literally “journey to the river’s ford”), and all of its encounters, mundane and metaphysical. In fact, one cannot understand how a Hindu experiences pilgrimage without a deep appreciation for the not-so-obvious concept of darshana, which means “sight or vision.” The direct encounter, or seeing, of the Divine, is the ideal that carries a Hindu on pilgrimage. He wants to see holy men and women, to see holy shrines, to see the images abiding in the ancient sanctums. Ultimately, he wants to see God, to have a personal, life-changing, bliss-engendering, karma-eradicating vision of Truth within himself. The pilgrim also wants to be seen by God, to reveal himself, uncover himself, stand before God and be known to Him. Darshana is the essence of every pilgrim’s journey, the rationale, the inner and outer goal. Working diligently with himself, the pilgrim observes his yogas and his sadhanas (disciplines) so that his seeing may be pure and untainted. Traditional questors’ practices of snana, the sacred bath, especially at the confluences of rivers, and mundana, shaving of the head, are part of attaining that purity.

Pilgrimage is a pan-human religious behavior, practiced by all cultures in much the same manner and for similar reasons–boons, expiation of sins, healing, nearness to God and enlightenment. A pilgrim of ancient Egypt testified, “I made myself a stranger to all vice and all Godlessness, was chaste for a considerable period, and offered the due incense in holy piety. I had a vision of God and found rest for my soul.” The Aborigines of Australia travel to Ayer’s Rock and other places of the continent. American Indian tribes undertake a “vision quest” at their sacred places. The Olympic Games were originally part of a pilgrimage to the temple of Zeus in Olympia, Greece. The Christians of the Middle Ages traveled to the holy city of Jerusalem, often at great personal peril. Muslims are expected once in their life to perform the hajj, the visit to Mecca, holiest city of Islam–about 10% are able to do so. Buddhists visit the four sanctified sites: Buddha’s birthplace in Lumbini, Nepal; his place of enlightenment at Bodhgaya, India; Deer Park (Sarnath), where he gave his first sermon; and Kusinara, where he had his great departure. Jains pilgrimage to Mount Abu in Rajasthan and Parasnath in Bihar; Sikhs to the Golden Temple at Amritsar; Shintoists to Mount Fiji in Japan. There are numerous places in China sacred to Taoists and Confucianists. Catholics are ardent pilgrims–four million a year to Lourdes in France, a million to Fatima in Portugal, to name just two destinations. Protestant Christians are possibly unique for rejecting the practice of pilgrimage as “childish and useless works.” But even they can be found at Lourdes or Jerusalem. Not only the practices but even the people are the same. What Hindu pilgrim would not recognize from his own experience the Christian characters of John Bunyan’s novel Pilgrim’s Progress–Mr. Worldly Wiseman, Mrs. Hopeful, Mr. Faithful, Mrs. Much-afraid and Mr. Ready-to-halt?

Pilgrimage is not a vacation, a chance to “get away from it all” and enjoy scenic vistas in far-off lands. The true blessing of pilgrimage comes with singlemindedness of purpose, rather than combining it (especially as a secondary purpose) with visits to relatives or the handling of business or professional concerns. Pilgrimage is a going toward holiness and a going away from worldly life. Sri Swami Satchidananda of the Integral Yoga Institute told Hinduism Today, “There is a tradition that when you take a pilgrimage you temporarily become a sannyasin [renunciate]. It is called yatra sannyasa. You go as a sannyasin, doing with simple things and depending on God.”

“Pilgrimages,” explains Swami Chidanand Saraswati (Muniji) of Parmath Niketan, in Rishikesh, “may be undertaken for realizing specific desires; as a prayashchitta (penance) for cleansing one’s sins or for spiritual regeneration. Seekers go on pilgrimages in quest of knowledge, enlightenment and liberation. The great acharyas like Shankara, Ramanuja and Madhva went on pilgrimages to teach Sanatana Dharma.” Pilgrims perform the shraddha rites at an auspicious place in honor of their ancestors. They seek the company of holy people. By such proximity, the pilgrim hopes to absorb a bit of the saint’s religious merit, or maybe to capture a glimpse of the lofty state of the knower’s consciousness.

The Mahabharata, in the Tirthayatra section, lists hundreds of holy destinations. Sage Pulastya describes to Bhishma a tour circumambulating all of India in a clockwise fashion, beginning from Pushkara in Rajasthan, then to Somnath and Dwarka in the West, to the Himalayas, across the top of India through Varanasi and Gaya to the mouth of the Ganges in the East, then southward to Kanyakumari, back up the western side of India to Gokarna in Karnataka, and ultimately returning to Pushkara. The existence of this pilgrimage route in ancient times proves, they say, that undivided India was a one culture unified by a one religion. In Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India, Surinder Mohan Bhardwaj states, “The number of Hindu sanctuaries in India is so large and the practice of pilgrimage so ubiquitous that the whole of India can be regarded as a vast sacred space organized into a system of pilgrimage centers and their fields.” The continuous circulation of tens of millions of pilgrims throughout India has forged a national unity of great strength. Swami Chidanand explains, “Pilgrimages have culturally and emotionally unified the Hindus. They have increased the generosity of people. Pilgrims learn and appreciate the many subcultures in the different regions, while also appreciating the overall unity.”

The pilgrim, according to Sage Pulastya, must have contentment, self-control and freedom from pride and anger. He must eat light, vegetarian food and regard all creatures as his own self. “The pilgrims,” notes Ma Yoga Shakti, “should not entertain anything which is not spiritual. A pilgrim must go with total surrender, with a total faith in God, that it is only with God’s grace that he can finish the pilgrimage.” All along the way, there is help from others. “People know you are a pilgrim,” Swami Satchidananda continued. “They say, ‘We cannot go ourselves. We are all busy in the world. Please, by helping you, you can go and get some benefit, and parts of it will come to us.’ ” Pilgrims often sense a divine guidance during their journey, as obstacles unexpectedly disappear and needed assistance comes in a timely, unplanned fashion. Helping pilgrims is an important obligation. The langar, free vegetarian kitchen, and free rest houses at pilgrimage sites are common methods of assistance.

In addition to participation in the normal temple or festival events, the pilgrim’s devotional practices include circumambulation, bathing, head shaving, sraddha offering to ancestors and prostration. Prostration and circumambulation are sometimes combined in the rigorous discipline of “measuring one’s length”–prostrating, rising, stepping forward two paces and prostrating repeatedly around a sacred site. There are pilgrims who undertake this formidable penance the entire 33-mile path around Mount Kailas. Many destinations have a prescribed set of observances for pilgrims. Some, such as that to the temple of Lord Ayappan in Sabarimala, have complex disciplines requiring months to complete.

Pilgrims pay obeisance to every Deity along their way. After worshiping at all the shrines in each temple, one finds a quiet place in meditation. Manasa puja, “mental ritual worship,” is then performed to the Deity who stands out most strongly in one’s mind, explained Swami Satchidananda. It is not enough to run from shrine to shrine taking darshana for “just five minutes,” as the tour guides insist. One must also reflect internally in meditation and thus become open to receiving the gracious boons of the God. Even a life-changing vision of God may come to the pilgrim in his meditation, or later in a dream.

H.H. Swami Prakashanand, an ardent devotee of Radha-Rani, explains how to conclude a sacred journey. “Normally while going to a holy place people think of God, but as soon as they have the darshan of the Deity and they start back home, their mind is totally engrossed in business affairs. This is not correct. While coming back he should be further engrossed in feeling the closeness of God. Otherwise it is a sight-seeing trip.” It is customary to return with holy water, vibhuti (holy ash) and other temple sacraments and place them upon the home altar after lighting a lamp. This establishes the holy places’ blessings in the home and keeps the pilgrimage alive for months.

DIVINE DESTINATIONS

The earliest pilgrimage destinations are thought to be the saptanadis (seven holy rivers), hence the Sanskrit term for pilgrimage, tirthayatra, literally “journey to the river’s ford.” These seven rivers–Ganga, Yamuna, Godavari, Sarasvati, Narmada, Sindhu and Kaveri–remain preeminent among holy sites on their own accord and in association with the temples along their course. Each Hindu sect holds certain sites in high regard, though few Hindus would pass up the opportunity to visit any of the great sanctuaries. Paramount is the Kumbha Mela, the largest gathering of humans in the world, according to the Guinness Book of World Records. The 1989 Kumbha Mela at Prayag drew 30 million devotees. The month-long festival is held four times in each 12-year cycle of Jupiter, once each at Haridwar, Prayag, Nassik and Ujjain. A bath in India’s sacred rivers yields immeasurable blessings. Hundreds of thousands of holy men emerge from caves and forests to bestow their blessings on humanity at the Kumbha Mela.

Haridwar, where the river Ganges enters the Gangetic Plain, is the gateway to the sacred Himalayan shrines, tirthas and ashrams. It attracts thousands of pilgrims year-round. The Kumbha Mela is held here when Jupiter is in Aquarius and the Sun in Aries–next occurring in January-February of 1998. Prayag, “place of sacrifice,” attracts millions who travel great distances and endure hardships for a purifying bath to absolve sins and seek moksha, freedom from rebirth, in the confluence of three rivers–Yamuna, Ganga and the invisible Sarasvati. This city holds the biggest Kumbha Mela of all when Jupiter is in Taurus and the Sun in Capricorn. The next one will be in January-February of 2001. Near the source of the Godavari River in Maharashtra, Nassik is revered as Lord Rama’s forest home during exile. One of ten cave temples here was Sita’s abode, from which Ravana abducted her. Shrines of the area include the Kapaleshvara and Tryambakeshvara Siva temples. The Nassik mela (festival) is much smaller than those of Haridwar and Prayag. It next occurs in August-September 2003, when both Jupiter and the Sun are in Leo. Historic Ujjain is one of India’s seven cities of liberation. This site of the relatively small 1992 Kumbha Mela, on the Shipra River in Madhya Pradesh, shelters an array of destinations, including the Mahakala Siva Temple and the Amareshvara Jyotir Linga. Its next mela will be April-May 2004, when Jupiter enters Leo with the Sun in Aries. A biannual Kumbha Mela of the South was begun in 1989 by Sri la Sri Tiruchi Mahaswamigal and Sri Sri Sri Balagangadharanathaswami of Bangalore at an auspicious site near Mysore.

Among the foremost religious retreats for Saivites is Chidambaram, the great Siva Nataraja temple, site of the Lingam of Akasha, located in Tamil Nadu. It was here that Lord Siva performed the Tandava dance of creation, overcoming the arrogance of the rishis, and where sage Patanjali later lived and wrote the Yoga Sutras. Here also lived Rishi Tirumular, author of the Tirumantiram. The glistening roof of the main sanctum contains 17,500 solid gold tiles, one for each breath a human takes in a day.

High north in Uttar Pradesh is Kedarnath, one of the twelve Jyotir Linga temples of Lord Siva. It was established at the foot of the Himalayas by the five Pandavas after the Mahabharata war to atone for their sins. Recent improvements have made the previously arduous ascent to this 12,000-foot sanctuary easier, but unfit trekkers are still cautioned about the cold and the 5,000-foot hike from Gaurikund, the last motorable outpost.

One of the greatest and most austere pilgrimages, Mount Kailas, Himalayan abode of Lord Siva, is sacred to five religions. Pilgrims perform a three-day, 33-mile circumambulation of the peak. At the foot of Kailas lies Lake Manasarovara, symbolizing a quieted mind, free from all thought. Kailas is the Mount Meru of Hindu cosmology, center of the universe. Within 50 miles are the sources of four of India’s auspicious rivers.

The Ramanathaswamy Siva Linga Temple at Ramesvaram near India’s southern tip was built by Lord Rama in penance for killing Ravana, a brahmin. Two Lingams (egg-shaped icons) are worshiped there, established by Sita and Hanuman. Each day the abhishekam (bathing) is performed with Ganges water. The temple is enormous in extent, with a mile of stone corridors. Pilgrims bathe in the sea and at 22 wells, each of which removes a particular kind of sin.

Pilgrims to Banaras, Siva’s City of Light, bathe at the ghats (river steps) along the River Ganges to cleanse the sins of a lifetime. Most pilgrims attend Siva Linga puja (devotional rites) at Kashi Vishwanatha, foremost of the 1,500 temples here. The devout journey here at life’s end.

One of the greatest Shakta temples is Vaishno Devi. Those who climb the mountain trail in the Trikuta mountains north of Jammu are rarely disappointed as they implore the Goddess for boons. It was here in the Himalayan foothills that Vaishno Devi, a devotee of Lord Vishnu, defeated the demon Bhaironatha. Though hidden within a cave, the shrine receives more than 20,000 pilgrims a day, even when wintery snows are piled deep outside.

At the very tip of India, where the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea meet, lies the ancient shrine of Kanyakumari, Goddess Parvati as the eternal virgin. It was here She defeated the demon Bana. Boats take pilgrims offshore to the Vivekananda Rock Memorial, where the young swami cognized his mission to begin a Hindu renaissance.

Madurai, the Athens of India, holds the labyrinthine Meenakshi Sundaram temple. Here Siva came as Somasundarar to wed the Pandyan Princess Meenakshi, a manifestation of Parvati. Thus, this edifice encases two temples, one to Siva and another to Sakti. The towering entry gates, 1,000-pillared hall, sacred tanks and shrines vibrate with thousands of years of worship at this seven-walled citadel on the Vagai River.

Only a few centuries ago the Kalighat temple was established in what was then a remote jungle near the river Ganges. The now highly congested Calcutta expanded to envelope the shrine, which is filled daily with devotees’ cries of “Kali Ma, Kali Ma,” beseeching blessings from the incomparable Protectress and Mother of liberation.

Kamaksha is the Goddess of Love. Her holiest sanctuary is a small temple built on the rock of Nila Hill near Gauhati in Assam. The town and its legends are described in the Mahabharata and the Kalika Purana. This temple of magic for the sincere devotee contains no image of the Goddess, but in the depths of the shrine is a cleft in the stone, adored as the yoni of Sakti.

Vaishnavites revere Ayodhya, birthplace of Lord Rama, “Jewel of the Solar Kings.” Here devotees worship and seek the blessings and boons of the seventh incarnation of God Vishnu. This orthodox Vaishnava town in Uttar Pradesh is among Hinduism’s seven most sacred cities. Temples and shrines in every quarter honor famous sites of Rama’s celebrated life, including the reclaimed Ram Janmabhoomi shrine and a temple to His devout servant, Hanuman.

Mathura is the birthplace of Lord Krishna, eighth incarnation of God Vishnu. Mathura and nearby Vrindaban and Gokula are an outdoor paradise for devotees visiting places of the Lord’s youth. A ten-mile circumambulation of the city takes enchanted pilgrims to dozens of shrines and bathing spots for this beloved God’s blessings.

Puri, in the state of Orissa, is the site of the famous Rathayatra, car festival, held around June each year at the sprawling, 900-year-old Jagannatha temple complex. A million pilgrims flock for darshana of God Vishnu as Lord of the Universe, and His brother and sister, Balabhadra and Subhadra. Using 500-meter ropes, throngs of devotees pull 40-foot-tall wooden chariots to the Gundicha temple.

Along with Yamunotri, Gangotri and Kedarnath, Badrinath lies in the area known as Uttarkhand, high in the Himalayas. During the half-year when not blocked by snow, hearty pilgrims climb 10,000 feet to the temple of Badrinarayana, where God Vishnu sits in meditation with a large diamond adorning His third eye and body bedecked with gems. Pilgrims take a purifying bath at the Tapt Kund, a sacred hot water pool.

India’s richest and most popular temple, Tirupati, daily draws 25,000 pilgrims. They joyfully wait hours for a precious two seconds of darshana of the two-meter tall, jet-black image of the wish-fulfilling Sri Venkateshwara, or Balaji. His diamond crown is the costliest ornament on Earth. The temple is a Dravidian masterpiece of stonework, gold and jewels. Head-shaving here is a prized testimony of penance and devotion, and famed laddu sweets are the pilgrim’s prized gift of blessed food.

In ancient times the rishis of the Rig Veda sang in praise of pilgrimage: “Flower-like the heels of the wanderer, his body grows and is fruitful; all his sins disappear, slain by the toil of his journeying.” So meaningful is pilgrimage in the Sanatana Dharma, the world’s oldest religion, that Hindus today have thousands of destinations, at which God awaits the pilgrim.

Recommended Resources: Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India [comprehensive study for North Indian sites], Surinder Mohan Bhardwaj, University of California Press, 2120 Berkeley Way, Berkeley, California, 94720. Pilgrimage Past and Present in the World Religions [useful for Western faiths], Simon Coleman and John Elsner, Harvard University Press, 79 Garden Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138-1425. Pilgrimages and Journeys, [fine children’s book], Katherine Prior, Thomson Learning, 115 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York, 10003. A Historical Atlas of South Asia [maps and historical accounts], Joseph E. Schwartzberg, Oxford University Press, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, 10016. Journeys to the Lands of the Gods [a pilgrim’s diary, especially good for South Indian sites], Rajalingam Rajathurai, Printworld Services Pte Ltd, 80 Genting Lane, #04-02 Genting Block, Ruby Industrial Complex, Singapore 349565