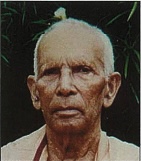

BY SWAMI RANGANATHANANDA MAHARAJ

The Sanatana Dharma is mainly the product of an extraordinary literature, the ten or twelve Upanishads, composed over 4,000 years, in which you find a scientific and experiential approach to religion. Religions of the world are generally based on unquestionable dogmas and creeds, but Sanatana Dharma is based on verified and verifiable truths of human nature, supersensory, but not supernatural. The supernatural has no place in Vedanta or Sanatana Dharma, because its concept of nature is very wide, including the Self or subject of knowledge along with sensory objects of knowledge. About the love of truth experienced by the sages of the Upanishads, Prof. Max Muller says, “If it seems strange to you that the old Indian philosophers should have known more about the soul than Greek or medieval or modern philosophers, let us remember that however much the telescopes for observing the stars of heaven have been improved, the observatories of the soul have remained much the same” (Three Lectures on the Vedanta Philosophy, London, 1894, p. 7). He went on to say, “It is surely astounding that such a system as the Vedanta should have been slowly elaborated by the indefatigable and intrepid thinkers of India thousands of years ago, a system that even now makes us feel giddy, as in mounting the last steps of the swaying spire of a Gothic cathedral. None of our philosophers, not excepting Heraclitus, Plato, Kant or Hegel, has ventured to erect such a spire, never frightened by storms or lightning. Stone follows on stone after regular succession after once the first step has been made, after once it has been clearly seen that in the beginning there can have been but One, as there will be but One in the end, whether we call it Atman or Brahman.”

The Bhagavad Gita speaks of Nature, or Prakriti, as two-fold: one, apara, “ordinary,” which is studied by physical sciences today, and the other para, which modern Western science has neglected, consisting of the spiritual principle of intelligence or consciousness. In a statement of the Gita, verse 6, chapter 7, Sankaracharya comments, “Sri Krishna, the Divine Incarnation, says, ‘I am the cause of this whole universe, through my two-fold Prakriti, or nature.’ Lower nature is composed of sensory data, which are constantly changing. The higher nature, namely, intelligence or consciousness, is the reality above the sensory level.” The sages discovered through investigation the Changeless behind the changing, the Immortal behind the mortal. That discovery, and the scientific technique employed for it, is expressed in one verse, the opening verse of the fourth chapter of the Katha Upanishad: “The Self-Existent Lord created the sense organs (including the mind) with the defect of an out-going disposition; therefore (man) perceives (things) outwardly, but not the inward Self. A certain dhira (wise man), desirous of immortality, turned his senses (including the mind) inward and realized the inner Self.”

Modern science has become aware of the influence of the datum of the observer on the knowledge of the observed data. If the Self as knower is inextricably involved in the knowledge of the not-self, of the known, an inquiry into the nature of the Self and the nature of knowledge becomes not only a valid but an indispensable and integral part of the scientific investigation into the nature of reality. The rishis who revealed the Upanishads were thus far in advance of human thought when they decided to dedicate themselves to tackling the inner world. By their emphasis on inner penetration, by their whole-hearted advocacy of what the Greeks centuries later promulgated in the dictum, “Man, know thyself,” but at which they themselves stopped half-way, the Upanishads not only gave a permanent orientation to Indian culture and thought, but also blazed a trail for subsequent philosophy in East and West.

This realization of the immortal Atman by one sage was re-experienced by other sages, and a thousand years later, by Bhagavan Buddha, and in our times by sages like Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother Sarada Devi and Swami Vivekananda. The Upanishads present religion as a matter of experience of the highest truth, and not as mere belief. “Knowledge of Brahman consummates in the experience of Brahman,” says Sankaracharya in his Brahma Sutra commentary. This is the supreme characteristic of Sanatana Dharma. Vedanta teaches the scientific-philosophical approach to the highest Reality. That approach is shown by Vedanta in its allowing and welcoming questioning by seekers. No dogmas can allow or stand questioning. Truth alone can do it. This idea has been expressed clearly in the Vedas, “This Atman [being] hidden in all beings, is not manifest [to all]. But [It] can be realized by all who are accustomed to inquire into subtle truths by means of their sharp and subtle reason” (Katha Upanishad, 3.12).

It was this Vedanta that Swami Vivekananda preached in his lectures in USA, England and India. In a brief utterance he says : “Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest this Divine within by controlling nature, external and internal.”

Physical science needed subtle minds to discover its great truths about matter, especially in the nuclear field. Still more subtle mind is needed to discover the infinite and immortal Atman, present in every human being. Because India had this scientific approach in the world of religion, it could practice tolerance and understanding and see the harmony between various paths to the Divine.

SWAMI RANGANATHANANDA MAHARAJ, 91, is President of the Ramakrishna Mission and Math, a monastic order of over 936 sannyasins and 403 brahmacharins, with 137 branches worldwide.