A GUIDE TO NEAT NUPTIALS

HOW TO ORGANIZE THE PERFECT HINDU MARRIAGE CEREMONY

By Tara Katir, Kapaa, Hawai

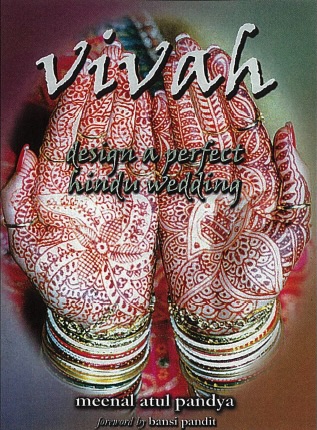

The Hindu marriage ceremony, vivaha samskara, is the most auspicious event of married life. Celebrating marriage’s central purpose–the mutual spiritual unfoldment of man and wife–the vivaha elevates a secular institution to a noble spiritual ideal. Alas, for Hindus growing up outside India the perfect wedding may be a blur of confusing possibilities. Fortunately, Meenal Atul Pandya has written a nifty little book just for those who are nuptially challenged, Vivah, Design a Perfect Hindu Wedding (104 pages, MeeRa Publications, us$24.95).

Pandya’s primary focus is on understanding the inner perspective of the samskara, or ceremony. The basic features of a marriage ceremony, with clear explanations and several color photos highlighting specific segments, furnish an excellent overview. The basic procedures of the Vedic marriage ritual have remained essentially the same throughout India for thousands of years, while unique regional styles and customs have also develped. This diversity bestows a rich variety, which is an integral aspect of the Hindu way of life. Several pages of Vivah are devoted to explaining Punjabi, Marathi, Gujarati, Tamil, Kashmiri and Bengali rituals. Sikh and Jain ceremonial practices are included as well to illustrate the close ties to the Vedic heritage.

The practical details of arranging a wedding can be overwhelming, so Pandya furnishes some down-to-earth advice for easing the harried couple and their families through the labyrinth of wedding experiences. From choosing the most auspicious date and time to finding a dependable caterer, her detailed planning guide covers every aspect of the preparations, ceremony and reception, starting one year in advance.

Acknowledging that many weddings in America have incorporated customs common here, explanations about flower girls, ring bearers and how to cut a wedding cake find a place alongside puja accessories, traditional jewelry, wedding pendants and the application of henna to the bride’s hands. An extensive list of resources available throughout the US can give you a head start in your search for a priest, perfect hall or caterer. A small glossary is included. The photographs that grace every page bring to life one of life’s most treasured moments. Not to be missed are the magnificent mehendied hands, a tribute to this delicate art. This is a great guidebook for an Indo-American bride and groom, or anyone who wants to learn more about the Hindu marriage ceremony.

Meera Publications, P.O. Box 812129 Wellesley, Massachusetts 02482-0014 USA. phone: 781.235.7441 web: www.meerapublications.com.

RELIGIOUS CROSS-OVER

A new paradigm is emerging in American religious beliefs and practice. Richard Cimino and Don Lattin in Shopping for Faith, American Religion in the New Millennium (237 pages, Jossey-Bass Publishers, us$25) take a close look at America’s changing religious landscape. Religiousness has traditionally been the province of churches, temples, synagogues and mosques. But in America today spirituality and faith are increasingly perceived as individual matters with few connections to a specific congregation or religious community. “Gallup polls show that seven in ten Americans believe that one can be religious without going to church. Clergy and denominational leaders dolefully note rampant individualism, even among members of their own congregations. They are particularly concerned about the growing number of ‘seekers’–those who have dropped out or never became institutionally involved, despite a keen personal interest in spirituality.”

Cimino and Lattin write, “Religions that emphasize their experiential and mystical dimensions rather than their moral, social or doctrinal sides have growing followings, although they are not necessarily showing institutional growth. Today’s experiential spirituality shares a need to know God personally without the intermediaries of church, congregation, priests and scripture.”

Eastern faiths such as Buddhism, Taoism and Hinduism are a part of this broad move toward experiential spirituality. The authors note that while many people will turn to the East for spiritual direction and inspiration, “relatively few will formally adopt these Eastern religions as monks, nuns or formal lay practitioners.” The genesis of this “East-meets-West” phenomenon is found in the writings of Thoreau and Emerson and the participation of Swami Vivekananda at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. “One hundred years later, members of these minority religions are finally entering the religious mainstream in the United States.” A Chicago interfaith leader observed, “We are no longer just dealing with European cultures. In the Chicago area, there are more Muslims than Jews, more Thai Buddhists than Episcopalians. There are 80,000 Hindus attending seventeen different temples in metropolitan Chicago. That’s the kind of diversity we’re talking about.”

The influx of religious diversity through generous immigration quotas, the Hindu Diaspora, the plethora of religious information available through the internet and America’s inherent religious tolerance all help create this atmosphere of change. Cimino and Lattin conclude that “religious communities that allow the flowering of personal spiritual experience may enjoy the brightest future. Shopping for faith may not be easy, and it may threaten the religious powers that be, but this uneasy mixture of practicality and personal faith will mark American religion in the new millennium.”

Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, California 94104 USA. web: www.josseybass.com.

ON WIDOW SACRIFICE

Sati is the name given to a wife’s immolating herself upon her husband’s funeral. Though illegal in India, it has happened as recently as November, 1999, in Mahoba, Rajasthan State. The event attracted far less publicity than the death of Roop Kanwar in the same fashion twelve years earlier, also in Rajasthan. But in both cases, reactions ranged from cries of “murder,” to reverential awe at the widow’s feat. In fact, police had to be posted at the Mahoba site to prevent a temple from being built upon it. The villagers protested the armed presence and, pointing to popular temples built in nearby areas to commemorate satis, demanded to know why they could not likewise honor their sati.

As Europeans encountered the Sanatana Dharma from the late 15th century through the era of the British Raj and beyond, a culture clash of gargantuan proportions was set to unfold. Of the many cultural misunderstandings that followed, a more emotionally-charged issue can hardly be imagined than the act of sati. In the scholarly book, Ashes of Immortality, Widow-Burning in India (334 pages, University of Chicago Press, us$16), Catherine Weinberger-Thomas “invites readers to set aside their personal prejudices and world views and enter the Hindu universe, in which humans and deities freely cross the borderline between heaven and earth, people are born and die again and again according to the laws of karma, and violent self-sacrifice is perceived as a path to immortality.”

Ritual suicide, as an act of loyalty, has been a part of Hindu experience for centuries. Tamil Sangam poetry “teems with references to heroic and devotional sacrifices” of all kinds. A sati is specifically “a woman’s immolating herself.” However, the British chose to regard it only as a form of murder. By 1817 widow sacrifice, as it was called by the British, was at the center of an emotional hurricane in England and India. In that year a report written at the request of the Supreme Court of Calcutta by Chief Pundit Mritunjoy Vidyalankar declared voluntary sati an option. “The Sastras, these scholars of Hindu law argued, far from recommending the [forced] sacrifice of widows, prescribe a life of abstinence, chastity and mortification for women who have lost their husbands, allowing them (with certain provisions) the possibility (should they so desire) of perishing with him on the funeral pyre.” However, by the following year, Raja Rammohun Roy, founder in 1828 of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious society of reformed Hinduism, published his first broadside against the burning of widows. And by 1829 Lord William Bentinck, then Governor-General of India, legally abolished it as an “inhuman and impious rite.”

Today, as in the past, the first question asked is whether a sati is forced by family, caste or religious belief to sacrifice herself. Thomas declares strongly that “according to one’s choice of viewpoint, one will interpret widow-burning as a form of suicide, sacrifice or murder. One could also consider the rite to be a form of torture inasmuch as the death of the husband is ascribed to sins committed by the wife in her past or present lives. By dying on the pyre the widow theoretically expiates her crimes. It is not a small matter to burn oneself alive. It is hard to imagine how women could conceive of such a plan, let alone carry it out, by simply yielding to the desires of external social actors. The problem disappears … as soon as one identifies the sacrifices … as murder. This is a basic tenet of the credo of ‘political correctness’ inside as well as outside of India. The very possibility that another version of the facts might exist is held to be intolerable, if not sacrilegious. In the wake of the outcry raised against the immolation of Roop Kanwar in Deorala, Rajasthan State, in September of 1987, one can appreciate the power of the censorship against any interpretation not in keeping with the dogma of the ‘widow-burning plot’.” In other words, few can encompass the idea of a voluntary suicide by fire, despite the many cases where there appeared to be no coercion.

Called “a national tragedy, a ‘Pagan sacrifice’ which ‘sullied the face of Indian democracy'” by the English-language press in India, satis and their worship continue unabated. Ashes of Immortality dares us to step beyond the emotional issue, to see beyond the “backlash or acculturation both by stigmatizing Hinduism and by conflating tradition with superstition, rural life with social backwardness and belief with retrograde obscurantism.” Thomas presents a controversial point of view that will undoubtedly inspire intense debate.

University of Chicago Press, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA. email: da@press.uchicago.edu.