By Vrindavanam S. Gopalakrishnan

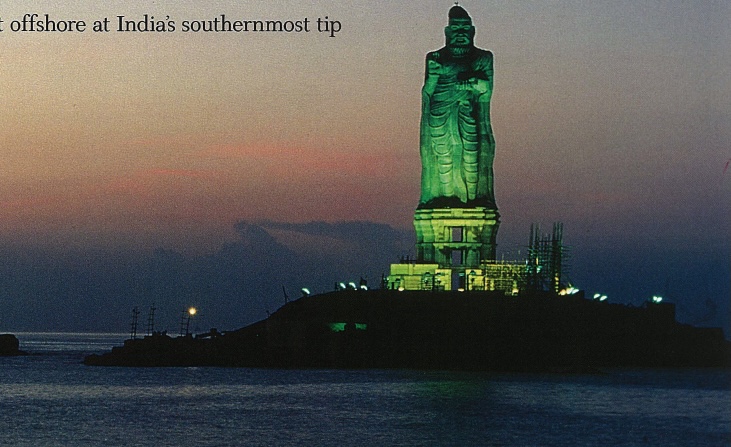

At six in the evening, January 1, 2000, India unveiled her own version of the Statue of Liberty. The 133-foot statue of Saint Tiruvalluvar inaugurated that evening by Tamil Nadu Chief Minister Dr. Muthu Karunanidhi is a monument not to political freedom or economic opportunity, but to righteous living and spiritual realization. Fifty thousand people gathered for the event at Kanya Kumari, the southernmost tip of India. The Chief Minister unveiled the flood-lit statue by remote control to cap two days of ceremonies. He called the statue a “beacon of light to guide human life for all time to come.”

Tiruvalluvar was author of the Tirukural (“Holy Couplets”), a 2,200-year-old South Indian Tamil classic on ethical living. The saint and his book are unfortunately little appreciated outside South India, where the scripture is held in such respect that it is sworn on in courts of law to this day. After studying Tirukural, Mahatma Gandhi said, “There is none who has given such a treasure of wisdom like him.” Christians, Jains and Buddhists have historically been so impressed with the text as to claim it their own. Here is a sample verse from the chapter on “Praising God.” “What has learning profited a man if it has not led him to worship the Good Feet of Him who is pure knowledge itself?”

Dr. V. Ganapati Sthapati, Tamil Nadu’s foremost traditional sculptor and architect, was honored at the unveiling for masterminding the project. He was chosen for the job over 300 master builders. The foundation stone was laid on September 6, 1990, while Karunanidhi was Chief Minister. Sthapati was selected to lead the project [see pages 26-27 for more on Sthapati]. His suggestion for an all-stone monument to the saint prevailed. He argued that stone would be more durable than metal, citing that America’s copper Statue of Liberty required extensive renovation just a century after its installation. The project stalled following Karunanidhi’s election loss. With his return to office, work recommenced in 1997.

The Tiruvalluvar statue itself is 95 feet tall, while the pedestal is 38 feet, thus making the total height 133 feet–equal to the number of chapters in the Tirukural. The height from the sea level to the head is 200 feet. The decision to keep the height of the pedestal at 38 feet also had meaning, said 72-year-old Sthapati, who was principal of the Government College of Architecture at Mahabalipuram until a decade ago. He explained that as the first 38 chapters of Tirukural deal with dharma, this was taken as a unit. “Then comes wealth and happiness respectively, and these constitute the body of Tiruvalluvar, the 95-foot unit.” Thus, he said, the poet’s statue stands on the firm base of dharma. By comparison, America’s Statue of Liberty is 151 feet tall, 56 feet taller than Valluvar. But Liberty weighs in at just 450,000 pounds, against Valluvar’s 14 million pounds–three times as heavy.

Sthapati set up three workshops in Chengalpet District for the work–at Kanyakumari, Ambasamudram and Shankarapuram. From Ambasamudram 5,000 tons of stones were quarried. For the outer portion 2,000 tons of extra-high quality and strong granite stones were quarried from Shankarapuram. Altogether, 7,000 tons of granite stones in 3,681 pieces, each weighing three to eight tons, were transported to the tiny island adjacent to Vivekananda Rock Memorial. The largest stones are 13 feet long and weigh over 15 tons. In fact, stones this heavy were previously used only in Mayan temples in South America, Sthapati said.

More than 150 workers, sculptors, assistants and supervisors worked for 30 months to complete the work by the end of 1999, at a cost of more than us$1 million.

Sthapati explained that before construction, a full-length wooden prototype was created, then cut into pieces and studied. To keep the statue standing erect in perfect equilibrium, an energy line was established (known in Vastu science as kayamadhyasutra), which is a cavity in the center of the statue from top to bottom. Sthapati made a prototype of each layer with bricks in his Chennai workshop, and from this the workers carved each layer’s stones. He said it was very difficult design work due to the statue’s curving nature, of a man standing relaxed and at ease, not straight.

The Tamil Nadu State engineers applauded the plan, “The design of the statue bears ample testimony to the engineering expertise of our forefathers handed down to generation after generation of our sthapatis.” According to Harsh Gupta, director of the National Geophysical Research Institute at Hyderabad India, the statue will withstand an earthquake of magnitude 6 on the Richter Scale occurring within 100 kilometers. This is far beyond any in the area’s recorded history, as the bedrock here is ancient and without known local faults.

The most difficult task was to procure the skilled labor needed. The number of artisans capable of working on granite stone is very limited in the country and only found in South India, especially in Tamil Nadu. However, Sthapati has a team of 150 workers, including highly experienced sculptors and chiselers. They worked sixteen hours a day to complete the work. Dressing the stones and chiseling them to specification is a tiresome job, said Shanmugham Sthapati, one of the supervisors. For example, the 19-foot-high face is made of several pieces. The ears, nose, eyes, mouth, forehead are all individual stones, carved with such precision that once joined it is difficult to distinguish the pieces. Nearly all work was done by hand, each carver wearing down 40 to 50 sharp chisels a day. According to Sthapati, the manual method on granite stones is the most dependable. Machines may tend break the stones and precision is difficult.

As the work progressed from the ground up, a massive framework of scaffolding was built with stumps of palmyra tree and poles of casuarina (ironwood, as strong as the name implies). To raise scaffolding to the top of the 133-foot tall statue, it took 18,000 casuarina poles lashed together with two truck loads of ropes, said Mr. Nagamuth of Rameshwaram, a project veteran.

The stoneworkers all felt the project to be their divine duty. “When we are on the job at the site, we don’t get tired at all even though we work for 16 hours. There is some divine power which keeps us energetic,” said Veluchami of Shankarankoil and Pannersiva Achari of Kovilpatti. Said Perumal Sthapati, a specialist in sculpture, a graduate of Mahabalipuram College and student of Ganapati Sthapati, “It is a God-given opportunity to work on such a wonderful project.”

The statue is an added attraction for tourists to Kanyakumari. Officials of the Vivekananda Kendra have agreed to a proposal to connect the two rock memorials by bridge. Visitors could then move easily from one island to the other, said Mr. Bhanu Das, Treasurer of the Kendra. Local residents, including non-Hindus, are pleased. “It is good that Tiruvalluvar has come up beside Swami Vivekananda,” said Viswanathan, a retired bank officer and native of Kanyakumari. Mr. Jesudasan, a Christian, said that the statue is highly acceptable to those who know the Tirukural and hence hold Saint Tiruvalluvar in reverence. The Tamil Nadu Tourism department is also delighted, and expects the number of visitors to Kanyakumari, now 1.5 million a year, to soar–easily repaying the state’s investment in the project.

While the world celebrated the millennium with gaiety and abandon, those in Kanyakumari witnessed something quite extraordinary. The entire region reverberated with divine music from the traditional drum and woodwind. Even the Thriveni, the confluence of two seas and the Indian Ocean joined the masses with punctuational rhythmic waves to join the whistling and banging. Together, man and nature celebrated the unveiling of the poet saint, Tiruvalluvar.

Click here to Read the Tirukural in Tamil and English at: http://www.himalayanacademy.com/view/weavers-wisdom [http://www.himalayanacademy.com/view/weavers-wisdom]