By Dao Thu Hien, Associated Press

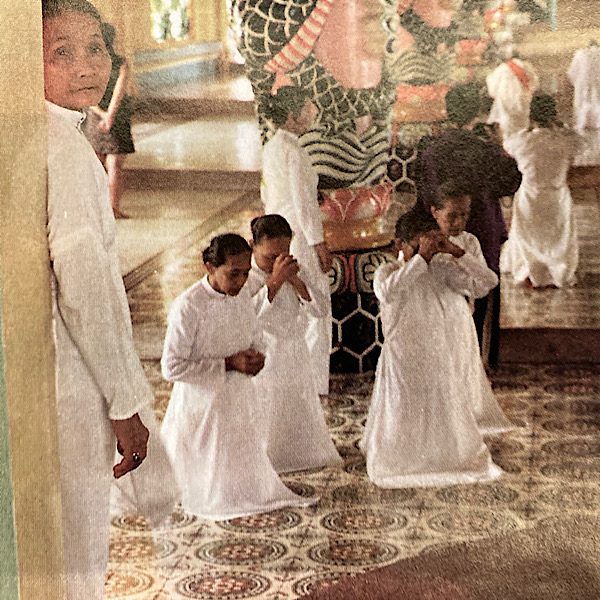

In the world of conformist communist Vietnam, the once banned Caodai religious sect is a splash of color with a zeal for the garish. Adherents commune with the spirits of historical figures, including Joan of Arc, Victor Hugo, Vladimir Lenin and, for more lighthearted seances, Charlie Chaplin. They look to the spirits of such people because their strong personality traits are models to others. Secluded in southern Vietnam’s Tay Ninh province, their main temple, decked out in blues, yellows and reds, borrows from religions around the globe in an effort to bridge the world of the living with the spirit world.

Founded in the 1920s, Caodaism is a hybrid of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Vietnamese spiritism, Christianity, Hinduism and Islam. The result is a jumbled code of ethics and tenets that has attracted more than three million followers despite the Vietnamese government’s control of religion. In addition to calling on spirits, Caodai believers practice priestly celibacy, vegetarianism and the worship of ancestors. The religion emphasizes morality and frowns on material luxuries, lust and deceit.

It’s a blend of East and West. Saints include modern China’s patriarch Sun Yat-Sen and Vietnam’s first poet-laureate, Nguyen Binh Khiem.

In early June, Caodai devotees got a big boost when the government gave their religion official sanction, legitimizing its existence in the eyes of the communist leadership. It had been a long struggle for a religious movement that raised an army to fight against the communists during the Vietnam War. But today, the government says Caodaism fills a void for many people. “We find the Caodai existence meets a legitimate spiritual demand of the people here,” said Muoi Thuong, a spokesman for the government’s Religious Affairs Committee in Tay Ninh. “These people are religious followers, but they are also good citizens and patriots,” Thuong said in a telephone interview from his office in Tay Ninh, sixty miles northwest of Ho Chi Minh City.

Established by Ngo Minh Chieu, a French-educated Vietnamese mystic, Caodaism once dominated Tay Ninh, controlling the religious and political affairs of the entire province. In 1975, when North Vietnamese troops overran US-backed South Vietnam, Caodaism was banned and the church’s lands were confiscated. But behind the scenes, the religion lived on, with its seance rituals and prayer meetings.

Today, Caodaism is practiced in about half of Vietnam’s provinces. In Tay Ninh, about 40 percent of the province’s 916,000 people are Caodai believers, and the number is expanding every year, Thuong said.