Each year Jaya Jaitly assembles a crafts bazaar in Delhi that charms the world

BY DIMPLE KAUL, NEW DELHI

IN JANUARY 2019, TEAM HINDUISM TODAY met a little-known woman who, by rights, should be widely recognized and lauded for her role in giving Indian handicrafts their place of pride and importance.

A meeting with Ms. Jaya Jaitly is inspiring. She is a lithe and gracious woman whose amiable nature is a great foil for her drive and determination. Welcoming us with a warm smile, she gave no inkling of the painful throat infection she was nursing. With equal steadfastness, she has been fighting and winning hard battles on behalf of craftsmen for a long, long time.

That is Jaya Jaitly for you. Even as she handled numerous operational issues that any exhibition would entail, she inspired the kaarigars (craftsmen and women) of her Dastkari Haat Samiti, which she founded in 1986, to lodge their protest against the high-handedness of the organizers of the Dilli Haat through the yellow ribbon campaign. She has single-handedly transformed the lives of many craftsmen across the country, providing them with training and acquainting them with techniques and technologies targeted at improving their trade and product marketing.

While lovingly tickling the ears of the canine that seems to have made Dilli Haat its residence, Jaya Ji explained to us that Dastkari Haat Samiti (DHS) is not just an association of craftsmen but a movement aimed at making the craftsmen thrive and propagate their art. She also spoke about the various workshops conducted by DHS in collaboration with various countries and their impact on the members.

All DHS members pay an annual membership fee for the sustenance of the organization. In turn, they enjoy a world of benefits that help them in their growth. The organization inspires them to go beyond the traditional motifs and experiment with material. Among the skills taught by DHS to its members is calligraphy. Development workshops equip members with the soft skills required to deftly meet the necessities of today’s trade, such as salesmenship, fair price display, respect for the customer and their own art, and the ability to photograph and showcase their artifacts. All these skills help DHS members expand their business.

So overwhelmed was one artiste upon learning calligraphy that he carved a “Tree of Life,” saying it signifies how “Talim Insan ko farsh se arsh tak pahunchati hai” (Education takes a man from the ground to the sky).

Dilli Haat is Jaya Ji’s baby, and she has nurtured it as such from the initial days, creating a disruptive concept that has been replicated across states. In spite of the present-day onslaught of alternatives for the customer, she recognizes that certain traditional products compete well, including handloomed fabrics, khadi cloth, chatai mats, and handmade utensils. She explained that at first the automation boom seemed to overshadow handicrafts through synthetics galore. However, the Indian government has been supporting handicrafts more than any other government in the world. Outside India, only private enterprises are involved in crafts. Indian handicrafts remain affordable primarily because of government support. However, the deeply bureaucratic governmental approach comes with a limited understanding of the sector. The “patronage mindset” towards handicrafts needs to go in order to offer a fresh lease on life and faster avenues of growth.

In the initial years, the government accepted advice from passionate people such as Pupul Jaykar and Kamala Rani Chattopadhyay who had an understanding of handicrafts. Later, Jaya Jaitly, who has been working from the ground up, was given credence and her input welcomed. Now, apparently, the government, steered by the IAS babus, claims to know everything and so listens to no one. The expertise and appreciation needed for guiding the nation’s artisans is visibly lacking. For example, the general sales tax on handicrafts began with 5% tax on handloom items and 12% on embroidery, which reveals a lack of understanding of this unorganized sector. And this unorganized nature meant that there was nobody to lobby for the craftsmen. Despite Jaya Ji’s stature as a recognized expert, approval and implementation of her recommendations is iffy and slow.

The crafts sector is a poster boy for job creation, and its success can ensure a stream of sustained employment through job creation. Most of the craftsmen that we spoke to employ people from outside their family and from among the community. The implementation of intelligently designed policies on travel, marketing and design would go a long way in developing the sector. Specialised platforms, skills upgrading and fostering communities would also help.

The government needs to realize that they will have to handhold the crafts community through non-governmental bodies, while being mindful of spurious organizations posing as handicrafts NGOs. Genuine work must not be neglected while these bodies get financially rewarded. In order to identify genuine people, the concerned officers will need a process to collect sound feedback, monitor schemes and build safeguards. Also, the system should be made easier for the artisans; at present the website is generally not responsive, and the current expenditure utilization form is tedious to complete.

Jaya Ji’s recommendation for categorizing the sector’s NGOs emphasizes the use of eligibility criteria, such as number of years of operation and presence across regions. Such a framework can ensure that only genuine outfits receive grants and that taxpayers’ money will not be swindled.

Our freewheeling interactions with some supremely talented, well-recognized artistes and craftsmen provided insight into the role that Jaya Ji and her organization have played in their lives at all levels. Dastkari Haat Samiti has created a democratic, egalitarian space that fosters collaborations and friendships across faiths, regions and genders. Every craft is based on the craftsmen’s own culture. Their lifestyle is reflected in their art, much of which depicts the Deities and embodies the devotion for them which pervades Hinduism.

In the following paragraphs, we attempt to share a glimpse of these hard-working, gifted people who through determination, openness and keenness to innovate have made a mark for themselves and their craft. Most are entrepreneurs, self-employed individuals who have created their own businesses which also provide employment to others in their community.

Block Printing

We first interview Arshad, whose block printing artifacts are showcased in stall number 16. Son of a Shilp Guru National Awardee, hailing from Pilkua, district Hapur, Faookhabad, Arshad comes from a family of artistes that has been inlaying silver in wood for years. His grandfather Anwar Hussain was a block maker, and his father experimented with various mediums from wood to brass. His children are studying in school, but they also go to his workshop regularly, as he wants them to continue the family legacy.

Arshad’s association with DHS began in 2004. He attended DHS workshops and learned calligraphy as part of Project Akshara, where craftsmen are taught Indic languages. He has worked with people from many countries, including Thailand and Indonesia. His initial designs were bereft of color, until a Thailand workshop gave him the idea of incorporating color. Jaya Ji gave him ideas for designs beyond the traditional, encouraging him to enhance his product range by including items of utility, such as note pads and lamp shades. He attributes his growth to the “marg darshan” that he received and the space and opportunity for sales. His customers’ love of his products gladdens his heart and inspires him to keep innovating. He particularly appreciates DHS because he can focus on his craft, knowing that the team is handling the operations, logistics, marketing and all the rest.

His only fear is that if automation is not controlled and the genuine concerns of craftsmen are not addressed by the administration, these traditional crafts might vanish. While he appreciates the introduction of technology, e-bidding and more, he urges the decision makers to be mindful of the skills and infrastructure at the craftsmen’s end.

Art on Cloth

We stop next at a Pattachitra (“cloth picture”) stall where the artiste, Shri Swain, is painting a white leopard with intricate motifs. Pattachitra is a traditional Orissi painting technique centered around the renowned Indian tales found in Ramayana, Krishna Leela, Bhagwan Jagannath and nature. The canvas, he explains, is made by joining cotton fabric using imli gum. The traditional motifs are painted on this cloth. Each piece requires many hours of hard work and intense focus, which few of today’s youngsters wish to undertake. Even if the money earned is no different, most would rather complete their education and “get a real job.”

Shri, however, grew up in the heritage village of Raghurajpur, near Puri, where almost everyone in the village, including his entire family, is engaged in one of the nine crafts for which the village is famous. His mother started it all by creating flowers from palm leaves, which foreigners would buy. Shri studied till 7th standard, then took training in palm leaf and Pattachitra styles, studying in Bhubaneswar for four years.

Shri met Jaya Ji shortly after finishing his training. His association with DHS has allowed him to visit Singapore and Sri Lanka to showcase his work. DHS has helped him explore new design ideas for today’s consumers. With modern technology, he can receive orders by phone. Before beginning a project, he sends a pencil drawing to the prospective buyer, who can be anywhere in the world, and he keeps them updated from time to time as he works. DHS has taught its members to transmit pictures properly, taking into consideration light and angles so that their work is impactfully displayed. Far from being a threat, mobile phones and the digital data revolution have been a boon for the craftsmen.

Shri particularly loves painting animals, and he has found that buyers are attracted to this form. He is teaching the craft to the elder of his two children.

Weaving in Wool

Wandering the exhibits, we encounter businessman and character Parvat Bhai from Sarli Gaon, (Bhuj, Kutch) Gujarat, who introduces to his woven masterpieces. Parvat learned the ropes from his father, who wove the Dhabla shawls of desi wool and sold them in nearby villages

In 1991 Pramukh Swami Maharaj of Akshar Dham took Parvat Bhai to the US for a three-month demonstration tour. In 1994 he received the Rashtriya Puruskar award, and in 2011 he qualified for India’s prestigious Geographical Indication tag, which is a huge endorsement and provides brand protection for his creations.

He employs around 40 men from his extended clan, as well as some 150 women who are mostly engaged in embroidery work. Everything is handmade. Parvat creates unique designs and colors, both natural and artificial. Both his sons are fully engaged in their father’s trade. He has been associated with DHS for more than 25 years, and theirs is the only exhibition that he attends in Dilli Haat. He appreciates their dedication to art and their hard work to ensure a platform for the craftsmen. Through them he has attended many International fairs.

Parvat Bhai likes to keep an eye on “what’s working in the market.” Ethnic traditional patterns serve as the foundation for his work, but he continually re-imagines products to address changing customer tastes. He proudly shows us his masterpiece stole which, he explains, “requires mind, heart, eye coordination on each thread” and takes almost a month to complete.

He has traveled the globe and continues to draw inspiration from everywhere. His biggest gripe is that artists are still expected to personally barter prices with every customer. To address that, he sets a fixed price and sticks to it, hoping people will wake up to the value and heritage that each of his creations represents.

Working in Wood

Neeraj Mohanwal, a graduate of Maharshi Dayanand University, hails from a family of five national award-winning craftsmen from Bahadurgarh in Haryana. He learned his woodworking craft at home and came to love it when he discovered that art creation kept him from getting bored. His rampant imagination manifests inventive patterns, and he often dreams of new designs in his sleep. Using specialized tools created by the family, he transfers his designs to the wood.

Neeraj’s great grandfather used to carve designs in ivory, but after it was banned in 1992, he started using sandalwood. When prices of that wood soared, he moved on to wood from the kadamba tree (Neolamarckia cadamba).

His father, Mahavir Prasad Monhawal, who won the National Award in 1979, pioneered the “undercut” technique which was later adopted by craftsmen in Agra and Rajasthan. Neeraj proudly displayed a wood carving of an elephant designed by his father—a masterpiece seemingly impossible to create. The family’s skills have brought many awards, including the National Award, a UNESCO award and a Shilpi Guru trophy. Neeraj won first prize in the 2015 State Award.

The entire clan is engaged in this singular art. They live together, work together and share one kitchen. Neeraj speaks proudly of his five-year-old son, who can already hold tools like a pro; but he explained that teaching the craft to the next generation will depend on the kids. For reasons of sustenance as well as legacy, he hopes the youth will continue in the tradition: “This work can be done at home, and no one needs to ever go hungry.”

Neeraj praises DHS for providing his clan with a platform to showcase their work through exhibitions, and for bringing buyers who place orders which are then fulfilled from home. He has attended workshops in Sri Lanka and Iran and says the exchange of ideas has helped him create new designs.

Silk Saris

Maqbool Aalam Ansari makes lovely silk saris. Beginning with his great, great grandfather, this National and State Award recipient and his extended family have been immersed in the world of weaving for generations. Everyone in his clan, in Bunkar Haat Kshetr, is involved in the craft. Men, women and children of the family chip in to carry the hand loom tradition forward. Knowing that weaving by hand could become extinct, they actively train people in their neighborhood in the craft. At one time Varanasi was witnessing a reduction in hand looming, but now, Maqbool observes, these arts are experiencing a renaissance.

Maqbool has always worked mostly with silk. One can feel the craftsman’s connection to his fabrics as he brings his creations before us, one after another. We are awed by the masterful fabrics. Traditional motifs are there, but also new designs. Earlier Maqbool would weave with mulberry silk, but now he uses moth silk, called Tussar and Moonga, to spin the threads. The weaving style is also being changed to ensure that the saris are not as heavy as earlier, for modern women prefer a lighter sari. When we asked if sari wearing has decreased in modern times, he responded that the trend has actually started to rise. He credits his two decades of association with DHS for giving him more exposure and a chance to experiment.

Toys

Lastly, we interviewed the soft-spoken but resolute Noor Salma from Karnataka, who spoke to us in fluent Hindi, breaking many stereotypes in one meeting. This gifted Channapatna lacquer artiste has been in the trade for thirty years. She recalled skipping school to learn the craft in her village. Daughter of an engineer father, she recounted how after losing her parents she turned her hobby into a profession. Her father-in-law encouraged her to pursue and persevere, and that is exactly what she did. She is proud of the struggle that she put up, especially as there were no NGOs when she started as an artiste. She spoke about improvements and innovations, such as the progress from paints to food-grade color in toys and the expansion of the range from Dussehra art to utility items such as candle stands and jars and even accessories such as necklaces.

Noor attends exhibitions to showcase her work and seek buyers. Her long-standing association with DHS has taken her to foreign lands such as South Africa and Sri Lanka, and she learned a lot from these experiences. Talking about her visit to South Africa she offered, “We think we have hardships here, but then we realize that there are women who face even greater hardships.”

Noor Salma believes in a blend of traditional with modern and has been awarded the Kamla Devi Award by the crafts council, the news of which she was given few days before this year’s event. Though her sons are not interested in the craft, she hopes to teach it to her daughters-in-law and grandkids in due course.

Conclusion

Though these artistes are highly skilled, few are familiar with the complete details of their craft. A proper induction into the history and evolution of their craft, in our view, could go a long way in continuing the legacy they bear.

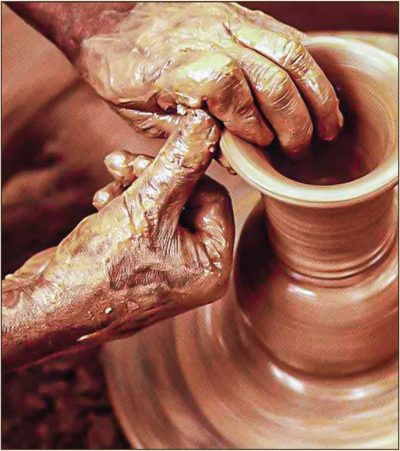

Pottery Factoids

Pottery is famous in most Asian countries and is considered one of the most iconic elements of Indian regional art. Its history, exquisite beauty and chic features have made it a modern form of Indian decor.

History indicates the art of pottery had its origins in India, in the Neolithic age. Evidence of pottery has been found during the Vedic period, the Indus Valley Civilization and also during the Mughal Period. Vedic pottery was handmade and unpainted, raw in nature and very utilitarian. These pots were used to store water during summer. Later, pottery was also used to manufacture plates, glasses, cups and even saucepans. There was a time when pottery was the main source of income for the traditional Indian business class.

The phase of painted pottery started in India during the 12th century, during the Mughal period. The Muslim rulers encouraged potters from Persia, Central Asia and the Middle East to come and settle in India. With the rise of pottery culture in India, Indian pots were exported to different parts of the world.

Red polished potteries are still widely found in Gujarat, Rajasthan and West Bengal. Modern India calls pottery by the Italian name terra-cotta, literally “baked earth.” The East Indian state of Orissa is the ambassador of terra-cotta handicrafts.

The ancient art of pottery has today become a chic and modern way to design and decorate traditional Indian homes. Architects and interior designers have learned that the presence of terra-cotta handicrafts creates an ambiance of warmth inside the home. The old has again become new.

Toys Are Not Just for Play

BY LIFESTYLE, NEW DELHI

Toys have existed in India since the Indus Valley Civilization 5,000 years back. Toys and games were not only meant to keep children entertained, but also to teach them how to develop their minds and understand what life had in store for them. Unlike the fancy and expensive toys sold in stores today, traditional Indian toys and games were simple and took their inspiration from nature. They were designed on the basis of how a child would react to them and how it would apply to real life.

Dolls: Quite unlike the dolls of today, traditional Indian dolls were made from the simplest materials, such as plant shoots, cloth and clay. At times, a mixture of cow dung, sawdust and clay were shaped into dolls and coated with bright paints. In northern India, Janmashtami is related in its entirety by means of clay dolls. In South India, the Dasara festival is called Bommai Kolu or a display of dolls. Traditionally, a married woman was supposed to add at least one doll to her collection every year.

Puppets: Puppets were not only the tools of skilled puppeteers, they were also used by parents to tell stories to their children. The children themselves used puppets to create their own stories, spurred by their imagination. It gave them a way to convey their emotions by transferring them to an inanimate object.

Bhatukli: These miniature versions of kitchen utensils and other household items were scaled down to the greatest detail and were made from copper and brass. These were played with by children as they watched their mothers cook and their family members make use of everyday household items. Today these miniature utensils give us an idea of what life was like in rural households.

Chaturaji: Four-handed Chaturaji is an apparent predecessor of modern chess. The game is played by four players, unlike two players on the conventional chess board. In addition, it involves a component of chance in the form of a single stick dice known as the daala. The players form two teams: Players 1 and 3 against players 2 and 4. Each player gets eight characters: four pawns, a king, an elephant, a horse and a ship.

Pachisi: The Pachisi board was made of cloth in a patchwork design. The four arms/limbs of the board are conjoined at the center, called charkoni. Each arm of the Pachisi has three marked squares, which are called “castles.” The game set comes with a set of 12 beehive-shaped wooden pawns in colors of yellow, black, red and green. The players throw cowrie shells on the charkoni, and the moves of the pawns are determined by the number on the shells that fall with the open face. Each player is allocated four pawns, and the objective of the game is to get all four to complete the round of the board before your opponents do. The game’s modern variants include Ludo and American Parcheesi.