How Hindus can and should participate in legislative prayer in the United States

BY ARVIND KRISHNAMOORTHY, MASSACHUSETTS, US

AT THE DAWN OF THIS CENTURY, THE late Prime Minister of India, Atal Behari Vajpayee, addressed a joint session of the US Congress. On this special occasion, for the very first time, a Hindu priest was invited to deliver the opening prayer in the House of Representatives. This was Venkatachalapathi Samuldrala from the Shiva Vishnu Temple in Parma, Ohio. Unfortunately, this historic event evoked protests in some conservative Christian media. Seven years later, the US Senate invited Hindu cleric Rajan Zed of Nevada to deliver an opening invocation, but he was interrupted by conservative Christian protesters even before the prayer began.

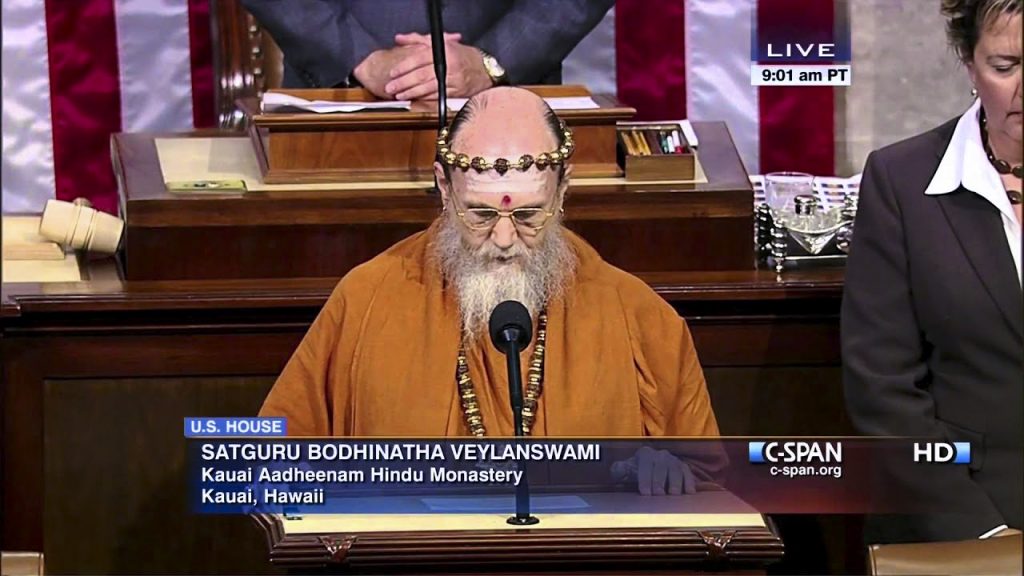

This intolerance to non-Christian invocations seemed to have died down by 2013, when Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami delivered the opening prayer in the US House. There have been Hindu invocations in several state legislatures since, and the positive trend has generally persisted, except for a lone 2015 boycott in the Idaho Senate.

Most legislators now seem to recognize that freedom of religion and diversity form the foundation of the United States, and they have given proper honor to Hindu invocations held in legislative chambers. Veeramani Ranganathan, a cofounder of the Hindu Temple of New Hampshire, delivered the opening prayer as Guest Chaplain in the New Hampshire House of Representatives in March 2019. Ranganathan recalled that the Speaker, legislators and staff were warm, welcoming, respectful and appreciative. He notes that such events help “spread a global message of religious tolerance and peaceful coexistence.”

Most people in India see the United States as a bastion of science and technology. When they hear about Hindu invocations in a legislative body, they are usually surprised by this seeming incongruity. They are unaware that, in the United States, the free exercise of one’s religion is a foundational principle enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Unlike India, where the Constitution affirms the equality of religions by adopting a secular posture, the US approach accommodates all faiths without favoring any one. In fact, a US Supreme Court opinion states that the Founding Fathers of the nation looked at prayer invocations as a practice whose effect harmonized with the tenets of some or all religions.

The United States Congress has opened its legislative sessions with prayer right from the first Congress in 1789. It borrowed this custom from the British parliament, which had observed the practice for a long time. Most state legislatures eventually adopted this same tradition. Founding Father Benjamin Franklin championed this custom in his speech to the Constitutional Convention: “I have lived, sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth; that God governs in the affairs of men… I therefore beg leave to move that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of heaven, and its blessing on our deliberations, be held in this assembly every morning before we proceed to business.”

The constitutionality of legislative prayers has been tested in courts. The US Supreme Court upheld their constitutionality in 1983 in its decision on Marsh, Nebraska State Treasurer, et al v. Chambers. The court ruled that Congress and state legislatures do not violate the US constitution’s separation of church and state even when clergy are paid to lead daily devotionals. Chief Justice Warren Burger, in the opinion he wrote on behalf of the majority, said that the use of legislative prayer “is not an establishment of religion or a step toward establishment; it is simply a tolerable acknowledgment of beliefs.”

Hindu temples and organizations in the United States can promote the integration of Hindus into the local community by making use of opportunities to lead legislative prayers. When a Hindu chaplain leads the general community in prayer, he or she not only brings recognition and visibility to the Hindu faith but also displays love and respect for people of other faiths in the community. This is indeed a great way of affirming the Hindu tenet that the world is one big family or “vasudhaiva kutumbakam.” This, in turn, can create a genuine feeling of inclusion in the community for Hindus, one which is based on an acceptance of what you truly are rather than just on professional connections.

Hindu prayers in legislatures can help remove distortions and misconceptions about Hinduism that are prevalent in the community. At the core of Hinduism are the notions of unity and pluralism. It asserts the oneness and interconnectedness of all life and the divinity inherent in all beings. It appreciates and affirms the validity of multiple perspectives and paths to approach the Divine. These abstract notions manifest themselves in Hindu life as core guiding values such as satya (truth), dharma, shanti(peace), prema (love), ahimsa (non-violence), and seva (service). Yet, respect for all life has been distorted in the mass mind as cow-worship, and pluralism as irrational polytheism.

“THE BILL FOR ESTABLISHING RELIGIOUS FREEDOM, the principles of which had, to a certain degree, been enacted before, I had drawn in all the latitude of reason and right. It still met with opposition; but, with some mutilations in the preamble, it was finally passed; and a singular proposition proved that its protection of opinion was meant to be universal. Where the preamble declares, that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed, by inserting the word ‘Jesus Christ,’ so that it should read, ‘a departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion;’ the insertion was rejected by a great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo, and Infidel of every denomination.”

Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father,

third president of the United States

President John Adams, a Founding Father of the United States, in his 1813 letter to President Thomas Jefferson, another Founding Father, talked about the sacred Hindu Shastras written in Sanskrit “with the elegance and sentiments of Plato,” and wondered, “Where is to be found Theology more orthodox or Philosophy more profound” than the Shastras that say “God is one, creator of all, Universal Sphere, without beginning, without End.”

Legislative prayers provide the opportunity to acquaint today’s political decision-makers and the broader community with the underlying core tenets of Hinduism, the wisdom of the Vedas, Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and other Hindu scriptures, as well as the beauty of the Sanskrit language and the peace of the prayer chants.

Professor Anil Saigal, the Asian American Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, says, “Hindu prayers at legislatures give a public validation to Hinduism as a well-respected religion. As Hindus, it is important for us to share our deep, scriptural wisdom for the benefit of all.”

Such public validation and sharing can be particularly helpful to the younger generations of Hindu children and youth, whose perception of Hinduism is colored by shallow or negative coverage in textbooks and the media. Images of Hindu prayers in legislatures, along with their universal messages of peace, tolerance, and oneness, can contribute to contemporary portrayals of Hinduism in textbooks that balance out or drive out stale, poorly informed or mischievous depictions.

There are around three million Hindus in the United States, and these legislative prayer events are an excellent opportunity to have our voice heard in the halls of power. Hindu temples and organizations have not made full use of this opportunity, either because of the protest incidents in the past or due to a lack of awareness or interest. They should reconsider and start exploring how they can take part in prayer services in legislative bodies.

The easiest way to start is to participate at the local level. Hinduism Today’s managing editor at Kauai’s Hindu Monastery says they have upon warm invitation “given blessings at the County council meetings, at Martin Luther King Day, Peace Day and the County Farm Fair—all very warmly welcomed.”

At the state or congressional level, such participation is usually arranged through politicians such as a congressional or state representative or senator. For example, Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami’s prayer service in Congress was arranged through the Hindu American Foundation by Rep. Ed Royce (R) of California’s 39th district and Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard (D) of Hawaii’s 2nd district. It read as follows: “May today’s session of the House of Representatives, to which Americans rightly turn for leadership, be abundantly blessed by the Lord Supreme. Through personal introspection, a collaborative heart and by God’s all-pervasive grace, may the members present here, despite differing views and staunchly held convictions, find the wisdom to craft mutually acceptable solutions to our nation’s challenges. The tragic Boston Marathon bombings, still vivid in all our minds, implore us to advocate the humanity of a nonviolent approach in all of life’s dimensions. Hindu scripture declares, without equivocation, that the highest of high ideals is to never knowingly harm anyone. May we, here in this chamber, and all the people of our great nation, endeavor to face even our greatest difficulties with an unwavering commitment to seek out and to find nonviolent solutions. Peace, peace, peace to us, and peace to all beings.”

Veeramani Ranganathan’s prayer service in the New Hampshire legislature was arranged through the efforts of State Rep. Latha Mangipudi (D). With today’s larger numbers of legislators of Indian origin, the process of arranging services by Hindu chaplains should be easier now.

State legislatures differ in whom they may call to deliver the prayer. Visiting chaplains and even guests are called in many bodies, but some chambers allow only a designated official of the legislature to deliver the prayer. Legislative assemblies also differ in their guidelines for delivery of the prayer. Some legislatures have no set guidelines at all. Others may set limits on the length of the prayer, require that the prayer be entirely in English, proscribe the mention of a particular political issue of the day, or require that the prayers be reviewed in advance. For example, Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami’s prayer in the Congressional House of Representatives was in English and less than 150 words, as required by the House Chaplain’s office. In contrast, Veeramani Ranganathan’s prayer service in the New Hampshire House was longer and was in Sanskrit, followed by an English translation.

Sanskrit chants do tend to have a musical quality about them and can produce a peaceful spiritual aura, even if the listener does not comprehend the meaning. The sounds of Vedic chants capture their divine essence, and music speaks to the soul.

In selecting the content and language of the prayer, it is important to keep in mind the guideline from the National Conference of Community and Justice to avoid religious sectarianism: “Accepting an invitation to lead the general community in prayer includes a genuine responsibility to be sensitive to the diversity of faiths among those in whose names the prayer is being offered.”

Participation in legislative prayers offers Hindus a unique opportunity to serve the community and promote integration into the American melting pot. It enables Hindus to assert the validity of their religion and nullify distorted perceptions of it. It provides a channel to share the deep wisdom of this eternal religion and to spread its lofty messages of tolerance, peace, love and universal brotherhood.