By ARCHANA DONGRE, Los ANGELES

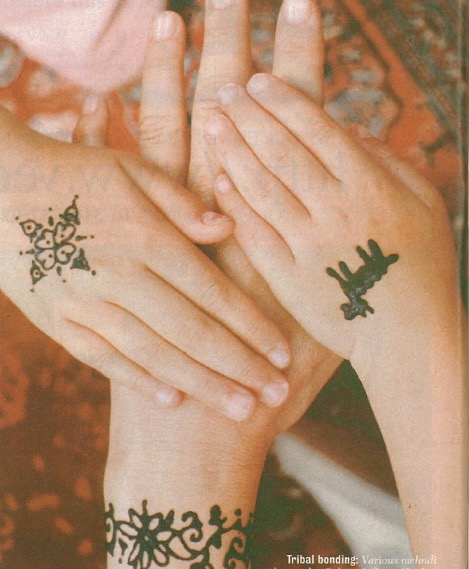

Growing up in India, the month of Shravan, right in the robust heart of the monsoon season, brought a special treat we little girls were fond of. As soon as the half-day school on Saturday was over, we would run to gather from the yards the fresh, tiny, emerald green leaves from lush mehndi bushes (henna, lawsonia inermis) that thrived in the monsoons, grind those leaves on the stone, add to it grandma’s special color enhancing ingredients, and by night we neighborhood girls would draw designs on each other’s palms with that pasty mixture. The event could be dubbed a friendship project of little girls’ bonding together. As the mixture dried the next morning, we looked forward to showing off the decorated hands to our peers at school on Monday.

The whole ritual just felt good. The cool touch of mehndi (pronounced ma-HEN-di) felt good on palms and fingers. Something in that mehndi just soothed our psyche, over and above making our hands pretty. Little did we know at the time that mehndi has mystical and spiritual powers, as well as a conditioning effect on the skin. Applied to the nerve centers of the palms and feet, it has a soothing effect on the nervous system.

Who ever knew at the time that the centuries-old Indian household art of mehndi, so imbued with mysticism and spirituality, and a time-tested custom for weddings and special occasions, would one day decorate the arms and shoulders of motorcycle-riding machos, TV and movie stars and become the darling of Western tattoo lovers?

The trend is hottest today in Los Angeles, where epidermis accessorizing is a cultured (and profitable) art form, but began in New York City. Last year, the Bridges and Bodell Gallery in New York’s East Village organized an exhibit of photographs of mehndi art. With the exhibit, the gallery offered mehndi designs to visitors willing to give it a try. “We thought we’d throw a couple of cushions on the floor and maybe a few people would have it done. But there were 300 people the first day,” said mehndi artist Loretta Roome, curator of the show. She learned the art of drawing mehndi designs from Rani Patel, who also developed a successful, secret recipe of mehndi mixture. The art so caught on with New Yorkers that thousands from all walks of life got mehndi done on them in the following months. Rani Patel has opened her own location, and Loretta Moore works out of a Moroccan store named “Gates of Marakash.” According to Nishit Patel, Rani’s husband, mehndi is popular with Black Americans.

The mehndi trend spread faster than the speed of gossip from New York, east to Europe and west to Los Angeles. Celebrities, housewives, men and women of all ages, races and hues are flocking to the mehndi parlors. Some of the more than 100 tattoo parlors in Los Angeles are thinking of augmenting their income with mehndi.

Carrine Fabius, 40, an artist from Haiti and owner of Galerie Lakaye in Los Angeles, became fascinated with mehndi when she saw it in New York last year. “The mehndi designs seemed so close to my heart because we have a women’s spiritual, body decorating art like that in our native Haitian Voodoo religion where I grew up.” A black woman, she owns the studio along with her artist husband Pascal Giacomini, a Frenchman. Her studio’s celebrity client list includes actress Angela Bassett, star of the film “What’s Love Got To Do with It;” television stars Neve Campbell from “Party of Five;” C.C.H. Pounder of “ER” and Britany Powell of “Pacific Palisades.”

American magazines and newspapers love the trend. The classy magazine InStyle sports Gwen Stephani of the band “No Doubt” with a bindi between her brows and mehndi designs on her forearms and wrists. Actress Liv Tyler displays full mehndi on her hands and feet in the May Vanity Fair. Vogue, Teen and Seventeen all have carried stories. Even Newsweek took note recently. “Los Angeles magazine was the first to pick up on the West coast the uniqueness of mehndi as a fashion and devoted nine pages to this ancient art,” Fabius said. USA Today and the Los Angeles Times ran features, and then almost every newspaper and TV station in Southern California.

Mehndi offers a painless and temporary alternative to tattooing. “Parents have brought in teenagers who wanted real tattoos, in hopes that a temporary mehndi design will satisfy their urge instead,” Fabius said. “Thirty-five percent of our clientele are men, who usually get it done on arms and shoulders in designs like dragons and snakes or somebody’s names,” she added. Her Galerie Lakaye has ten mehndi artists, and two or three are on hand at any given time. The prices start at $20 for a simple palm or wrist design and then go up according to complexity and extent of design. Designs chosen are similar to traditional, from the Galerie file of graphic arts, floral and animal designs or Mexican and Haitian tribal art. Palms, arms and wrists are more common locations, but ladies have also done it around the navel or on their backs.

The business sense that prompted Fabius to open her studio at Galerie Lakaye propels her next project currently in the works. She and a chemist are developing a henna formula with a longer shelf life. Henna paste has to be fresh to be effective. The new product will be sold under the label of “Earth Henna” from September 1997. “The possibilities are limitless. Many parlors in Europe are asking for the paste. In Asia, Japanese women have taken the trend seriously. There are inquiries for franchise-like operations from all over. We can sell the paste commercially and train the artists as well, or sell to individuals who want to do it themselves at home,” Fabius said. Who knows where this henna mania will go?

Galerie Lakaye, 1550 North Curson Avenue, Los Angeles, California, 90046, USA;

Temptu, 26 West 17th Street, New York, New York, 10011, USA (for a Mehndhi-like home-applied product)