Our consciousness has gone in-to a slumber. Our sensitivity has slipped into a strange coma,” laments activist Rakesh Kumar Jaiswal of Kanpur, a city of one million 400 km southeast of Delhi. “People need to be awakened to the problem of Ganga pollution.” His Eco-Friends organization is one of a handful trying desperately to awaken India and the world to the present pitiful plight of Ganga Mata, Mother Ganges. She is polluted by enormous quantities of human and industrial waste. Disease-causing organisms and poisonous chemicals abound in Her ever-sacred waters. Rampant illness, disability and early death is the result, a tremendous drain upon India’s human resources. Payal Sampat is a staff researcher at The Worldwatch Institute, a renowned social and environmental think tank. This report is condensed from her original analysis published in World Watch magazine, July/August, 1996.

SPECIAL REPORT

By Payal Sampat

The Worldwatch Institute, Washington, D.C.

According to Hindu mythology, the Ganges river of India–the Goddess Ganga–came down to the Earth from the skies. As the river rushed down, God Siva stood waiting on the peaks of the Himalayas to catch it in His matted locks. From His hair, it began its journey across the Indian subcontinent. Whatever one makes of this myth, the Ganga does, in fact, carry extraordinary powers of both creation and destruction in its long descent from the Himalayas. At its source, it springs as melted ice from an immense glacial cave lined with icicles that do look like long strands of hair. Today the river symbolizes purification to millions of Hindus the world over, who believe that drinking or bathing in its waters will lead to moksha, or salvation.

There may be a scientific as well as religious basis for the beliefs that this river can bring purification. According to environmental engineer D.S. Bhargava, the Ganga decomposes organic waste 15 to 25 times faster than other rivers. This finding has never been fully explained. The Ganga has an extraordinarily high rate of reaeration (the process by which it absorbs atmospheric oxygen), and it can retain dissolved oxygen much longer than water from other rivers. This could explain why bottled water from the Ganga reportedly does not putrefy even after many years of storage.

Today the Ganga supports a staggering 400 million people along its 2,510 kilometer (1,560 mile) course. If the delta it shares with the mouth of the Brahmaputra River is included, the number of people it supports rises to half a billion, or nearly one-tenth of all humanity, making it the most populous river basin in the world.

Over 29 cities, 70 towns and thousands of villages extend along the Ganga’s banks. Nearly all of their sewage–over 1.3 billion liters per day–goes directly into the river, along with thousands of animal carcasses, mainly cattle. Another 260 million liters of industrial waste are added to this by hundreds of factories along the river’s banks.

The result is deeply ironic: this ancient symbol of purity and cleansing has become, over much of its length, a great open sewer. The transformation began centuries ago, when the basin’s rich cropland and abundant wildlife made it a perfect place for human settlement. For a long time, the river seemed impervious to damage; its enormous volume of water diluted or decomposed waste very rapidly, and the annual monsoons regularly flushed it out. With 20th century pressures of burgeoning population and industrial growth, the Ganga is teetering under the burden placed on its cleansing capacities.

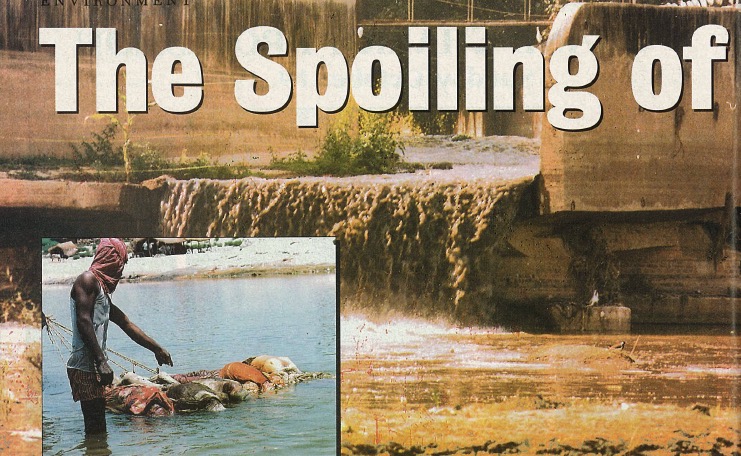

From the mountains to the sea: It is at Rishikesh that the defilement begins, as raw sewage is dumped into the river along with hydrochloric acid, acetone and other effluents from large pharmaceutical companies, and heavy metals and chlorinated solvents from electronics plants. From Rishikesh on, the river is never able to regain its balance before the next onslaught of unsought offerings comes its way. Perhaps the worst assaults occur at the city of Kanpur, where the hides of horses, goats and cattle are brought to factories for tanning. Some 80 tanneries operate here, consuming and discharging large quantities of water as skins go through an extensive chemical treatment from the time they are scoured with lime to when they are treated with chromium salts. The chromium lends a greenish hue to the drinking water the city draws from the river. Organic wastes–hair, flesh and other animal remains–are thrown into the river, giving it a fetid stench. As they sink into the water, they mingle with the effluents of some 70 other industrial plants–mainly sugar factories that disgorge a thick molasses-like substance, and textile companies that throw in various bleaches, dyes and acids. Kanpur also contributes to the river about 400 million liters of sewage each day.

Another dose of nitrates and phosphorus comes straight from the Indian Farmers Fertilizer Cooperative, a group of fertilizer factories just before the city of Allahabad. Thus laden–with mud, raw sewage, heavy metals, fertilizers and pesticides–the river heads east toward its junction with another great river, the Yamuna. Unfortunately, what might have been a fresh infusion of water here is not to be. The Yamuna, it turns out, has a sorry saga of its own. Flowing parallel to the Ganga just a little to the west, the Yamuna passes through New Delhi, picking up another massive quantity of sewage and other pollutants. At Allahabad, the now voluminous Ganga receives an additional load of 150 million liters of sewage each day.

About 150 kilometers east of Allahabad, the Ganga reaches Varanasi (Banaras), the place most associated with the river by its devotees. Varanasi is one of India’s oldest cities, and is considered to be its holiest. Its sewer system was built by the British in 1917, designed to serve one-tenth the population of the city today. This antiquated system does little more than pipe raw sewage into the river.

Multitudes of pilgrims come to Varanasi to bathe in the Ganga and drink its water, convinced of its purifying qualities–and undissuaded by the fact that coliform bacteria levels here far exceed the limits considered safe. The World Health Organization standards for drinking water stipulate coliform levels of no more than 10 per 100 milliliters of water. In Varanasi, coliform counts are as high as 100,000 per 100 ml. Elsewhere in the river, they range from 4,500 upstream to 120,000 downstream. Not surprisingly, water-related ailments like amoebic dysentery, gastro-enteritis, tape-worm infestations, typhoid, cholera and viral hepatitis are extremely common in the Gangetic region. One person in the region dies of diarrhea every minute, and eight of every 10 people in Calcutta suffer from amoebic dysentery each year.

The river moves on to Bihar’s capital, Patna, a major producer of agricultural chemicals, where the water undergoes still further alteration. Farther downstream, the large oil refinery at Barauni is notorious for piping huge amounts of oily sludge into the river. Ten years ago at this location, a two-kilometer stretch of the river caught fire and burned for 16 hours.

When the Ganga enters West Bengal, it branches into the Hooghly, which turns south toward Calcutta. About 150 large industrial plants are lined up on the banks of the Hooghly at Calcutta. Together, these plants contribute 30 percent of the total industrial effluent reaching the mouths of the Ganga. Of this, half comes from pulp and paper industries which discharge a dark brown, oxygen-craving slurry of bark and wood fiber, mercury and other heavy metals which accumulate in fish tissues and chemical toxins like bleaches and dyes, which produce dioxin and other persistent compounds. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency has set a standard for suspended solids at 100 particles per liter of water, but the count in the Hooghly is over 6,000.

Toward a bleak future: Despite the long history of the river’s desecration, what has happened to date may pale beside what awaits this region if current practices continue. The population of the basin is projected to reach almost a billion people in the next generation. This would mean 2.5 billion liters of sewage, or double today’s quantity, and 2 billion liters of industrial effluents discharged into the river each day by the year 2020.

In any life process, whether that of an individual organism or a large ecosystem, gradually increasing stress does not result simply in gradually increasing impairment; at some point the whole process collapses–as is now happening in the Ganga. If this continues much longer, the Ganga will become incapable of serving its traditional waste-removal function, or of providing usable water for industries or homes. Already, 40 million workdays and millions of rupees in health services are lost each year due to diseases the river carries. With a collapse of basic freshwater services, those losses could explode.

The link between the river’s health and that of the region it sustains has been given short shrift by policymakers. In 1985, the Indian government launched an Action Plan to clean the river, but it failed abjectly–due to pervasive corruption, mismanagement and technological bungling–and was duly abandoned. A fundamental reason for the failure was that most of those who have a stake in the river’s health were never included in the planning. But as conditions have worsened, the prospect of having their life-support system incapacitated may spur concerned industrialists, farmers, public health officials and ecologists to succeed where the bureaucrats failed. The spiritual role of the river, too, could provide a powerful force for change. Dr. V.B. Mishra, a Hindu priest and professor of hydraulic engineering who leads the Clean Ganga Campaign in Varanasi, tells adherents that the river’s sacredness is reason enough to preserve it.

To observers in other parts of the world, the case of the Ganga may seem uniquely horrific; it may be hard to grasp how people could knowingly put raw sewage into the same water they bathe in or drink. Yet, what has happened here is fundamentally no different from the continued abuse of ecosystems all over the world. Whether it is the contamination of groundwater by nuclear waste in Russia, the bioaccumulation of toxic chemicals in fish, or the killing of thousands of lakes by acid rain in Scandinavia, the long-range risks are no less alarming.

To the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia or the Ganga valley, there was possibly no greater crime than the desecration of a river. Despite all we know about the consequences of our polluting actions, we repudiate this respectful relationship with the resources on which we depend. It is a relationship that neither India nor the world can continue to ignore.

Worldwatch Institute, 1776 Massachusetts, Avenue, Washington, DC, 20036, USA

A Handful of Organizations are actively working to clean up the Ganga. Dr. Veer Bhadra Mishra, “Mahantji,” and his local Sankat Mochan Foundation and international support group, Friends of the Ganges, concentrates on Banaras. According to Mahantji, an expensive sewage system built under the Ganga Action Plan does not function as planned and has resulted in sewage flooding into city streets. He advocates a new, passive system which will shunt all sewage downstream below the city into low-tech oxidation ponds. American Fran Peavey, president of Friends of the Ganges, told Hinduism Today, “If we can fix pollution here in this holy city, it will be a model for the rest of India.” She is an example of how non-Indians can be inspired to help. “You don’t have to be an Indian to love Ganga,” she said. “I fell in love with the river when I first came here 16 years ago. Something happened to me that was not comprehensible in normal thinking.”

Jaiswal of Eco-Friends is concentrated on the Kanpur area. Jaiswal canvassed thousands of saints and sadhus at the 1995 Ardra Kumbha Mela at Allahabad, but found himself in competition with other hot political issues such as Ramjanma Bhoomi and was only modestly successful in explaining the river’s plight to a few religious leaders.

What can you do? The pollution problems described in this article can be permanently solved only by the government. It will take decades and billions of dollars. So what should we do in the meantime? People in Western countries have lived with seriously polluted waterways for centuries. They don’t swim in a river unless they know for certain it is not dangerously polluted. No one in the United States would drink directly from the Mississippi, a river with half the water flow of Ganga. No Western nation is attempting to clean up a river or lake to the extent one could drink from it; rather the focus has been on supplying purified water by pipes. This too might be a better goal for India’s cities than to completely depollute the rivers.

Because the rivers in India are cleaner at some times of the year than others, festivals and pilgrimages centered around the rivers could be adjusted accordingly. Those bathing at rivers where pollution is a significant hazard should be systematically warned and advised on how to protect themselves. The many temples and ashrams along the Ganga can take a role in this public education, and all Hindus can help Mahantji, Jaiswal, Mehta and others clean the Ganges.

Contacts: Sankat Mochan Foundation, b1/45, Varanasi, 221 005, India. Friends of the Ganges, 3181 Mission Street, #30, San Francisco, California 94110, USA. Eco-Friends, Post Box 287, Kanpur, 208001,India.