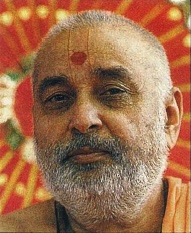

BY SADHU VIVEKJIVANDAS

The recent Glenn Hoddle controversy, that cost him his us$575,600-a-year job as England’s soccer coach, seems to have erupted from a misrepresentation of his belief in karma [Hinduism Today, May, 1999, page 28; September, 1999, page 13]. In an interview with The Time’s reporter, Matt Dickinson, on February 1, Hoddle said, “You have to come back to learn and face some of the things you have done, good and bad. You and I have been physically given two hands and two legs and half-decent brains. Some people have not been born like that for a reason. The karma is working from another lifetime. I have nothing to hide about that. It is not only people with disabilities. What you sow, you have to reap.” Matt Dickinson reported this with a twist, “It’s Glenn Hoddle’s controversial belief that the disabled, and others, are being punished for sins in a former life…”

Despite the uproar and reactions in England to Hoddle’s personal belief in karma, one must bear in mind that the adverse reactions do not eclipse the Hindu view of karma or make it unacceptable. Hinduism’s principle of karma provides valid and logical answers to the disparities and varieties of life. The principle of karma should not be lost because of the Hoddle controversy.

Indian sages conceived of life, within both the micro and macro-cosmic spheres, not as a steady state but as a process, a passage of souls from one birth to another. To understand the karma theory, one has to accept the Hindu concept of rebirth. This process and its outcome are directly related to the karmas, good or bad actions, of individual souls. We are what we are because of our actions. Every action has a result; some may be immediate, some however are accumulated untill they reach a point of manifestation. There is nothing arbitrary in the entire working of nature. All that has come to be in one form or another is due to karma. Behind every individual’s existence lies his own past deeds. There is a cause for every event, pleasant or painful, that takes place in this lifespan.

The karma theory says there is a causal nexus between the cause and the effect in the physical universe. Karma itself does not determine the amount of reward or punishment that a person deserves with respect to his karmas. Hence God is the agency that decides and dispenses reward or punishment according to the quality of the actions performed by the person. So, karma is not the ultimate giver of fruits, according to Vaishnava and Vedanta traditions. It is God who decides what and how much to give for one’s actions.

God gives man the freedom of choice, and he exercises his choice. But when he misuses it, then God ensures that he gets the appropriate result. So, man is ultimately responsible for his own actions. The law of karma conveys the responsibility for one’s actions, inequities and anomalies in the lives of people. So a person is accountable for what he is because of his good and bad deeds.

The Brihadarayanka Upanishad says: “Whatever actions one does, so does one become. One who performs good actions becomes good. And one who performs bad actions becomes bad.” (4-4-5) The Padma Purana says, “By his own karma a creature becomes a god, man, animal, bird or immovable thing.” (2.94.12) Manu Dharma Shastras and Yagnavalkya Smruti (moral codes) speak of the three-fold origin of karma, namely, mind, speech and body. The consequence of a sinful mental action is a low birth, evil verbal action is a bird or a beast and wicked physical action is even lower than that. The Brahma Sutras by Veda Vyasa says, “God is not partial or biased in giving happiness and misery to anyone, but gives the fruits of one’s karmas (actions.).” (2-1-34)

Lord Swaminarayan has also said that, “God grants each soul a body according to its previous karmas.” (Vachanamrut Gadhada I-13). Moreover, all things have three types of karmas, namely, sanchita, kriyamana and prarabdha. Sanchita means the stock of karmas or accumulation of good and bad actions. Kriyamana means the new karmas we perform in this birth. And prarabdha karma, a portion of karmas extracted from the sanchita karma, creates the present life circumstance, including the physical body. So our shapes and forms and our experiences of pain and joy are, in fact, a result of our own karmas.

The Hindu explanation through the karma principle very lucidly answers and explains the disparities between individuals and all things. The karma principle is a moral law that replies to the actions of all living things–even if some people in London don’t like it. When we humans have our own structured judicial system to judge and penalize our actions, then what of the vast complex, sophisticated creation of God! The karma principle, seen objectively and not mindlessly rejected because of its origin as a Hindu principle, should surely appeal to all humans as a legitimate answer to the problems and reactions we face in life. Accepting and understanding that our actions have effects and causes may restrain man or make him aware of his wayward or unwarranted activities. And if we do not accept the karma principle, then who is to be blamed for the distinctions and disparities we find in humans? Is God responsible, or is it our parents or the environment? The fact that many of the reactions we experience in our daily dealings and relationships are responses to our own or another’s actions is logical, appealing and worthy of faith.