PHOTOGRAPHS BY THOMAS L. KELLY

By Dr. Hari Bansh Jha, Kathmandu, Nepal

In the Hindu Kingdom of Nepal, one need not look long or hard to deduce that this is a country with a penchant for works of wood. Especially in the capital, Kathmandu, it is difficult to find a structure without some exquisite designs wrought in wood, be they in doors, windows, roof struts, a balustrade or veranda. Multi-tiered, pagoda-style temples and royal palaces are the foremost repositories of intricate carvings, though all homes and businesses display ornate embellishments to some degree, according to their means. The craft itself, still perpetuated through hereditary artisans, is one of the most precious cultural assets of this country.

Woodcarving in Nepal has been most highly developed in the Kathmandu Valley, which comprises Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Lalitpur districts. These three are home to the world’s rarest wooden art. Perhaps nowhere else in the world are the carvings as sophisticated, dramatic and extensively incorporated in construction. Even the name, “Kathmandu,” indicates the unique focus of this area. Derived from the Sanskrit word kastamandap, which is the conjunction of kasta, meaning wood and mandapa, meaning temple or hall, Kathmandu means “temple made of wood.”

At the western edge of Kathmandu’s Durbar Square one finds the structure known as Kastamandap, the oldest surviving timber structure in the valley, its three tiers of pagoda roof rising fifty feet above a long veranda. The structure dates back 800 years, and legend tells how it was constructed entirely from the trunk of a single sal tree (Shorea robusta). Yet with the extent of wooden temples and iconography throughout Kathmandu and vicinities, a more accurate definition of “Kathmandu” would be “city of temples made of wood.”

Temple pillars, Deity icons and palace portals display the epitome of local carving skill. Apart from these, the predominant use of elaborate woodwork is in doorways and windows of the wealthy, though even common households strive to embellish their structures. Usually, frames of doors and windows are made of hardwood–a painstaking job. Hardwoods are first seasoned for a number of years so that the doors and windows can last for centuries. Frames are primarily carved with floral designs. The doors themselves are usually made of softwood and carved with images of Gods and Goddesses. But wherever the doors are exposed to harsh conditions, they are made of hardwood as well. Some are decorated with the eyes of Buddha. Others have designs of the traditional religious water pot, kalash, fish and flowers, all symbols of good fortune.

The Nepalese have developed woodcarved windows as has no other culture [see inside front cover]. Apart from many standard options, the preferred ornamental designs are the lotus window, mesh, chariot, peacock and oriel windows. Windows in Nepal serve a higher function than those of Western architecture. They are not mere inlets for air and light, but are portals of peace and beauty. Sculpted upon them are images of Gods and Goddesses who are expected to protect residents within from evil forces. Certain windows are not even meant for looking through. Their main function is artistic and symbolic. As such, many styles of window do not open. The option to peer out is found mostly in balcony windows, through which modest and reserved women can view the happenings in the city without becoming involved. Such windows are symbols of higher social and economic status of those people.

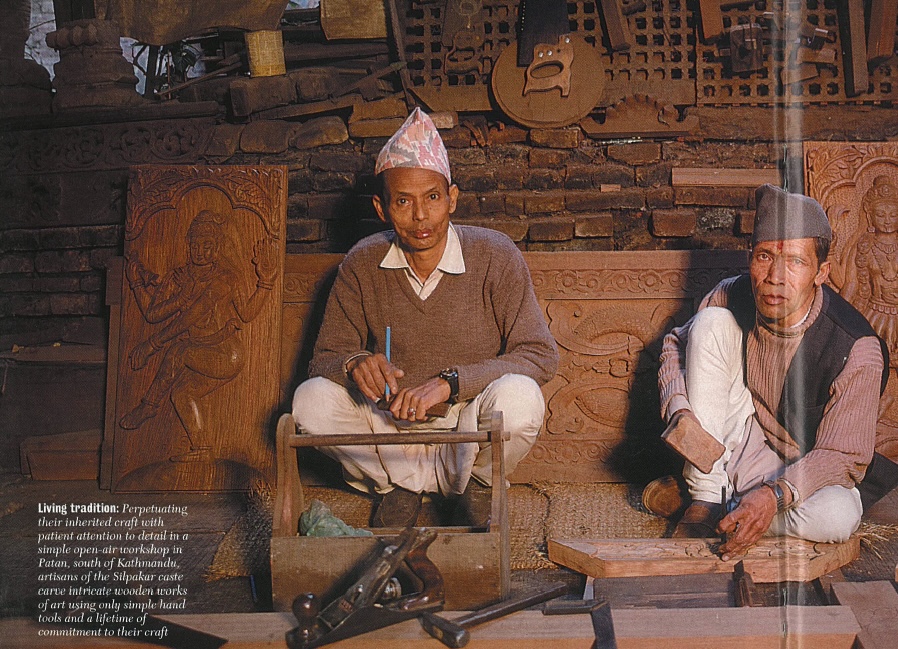

The Nepalese woodcarving tools are simple and traditional: chisel, adze, handsaw, wooden mallet and jack plane. Craftsmen embellish wood for interior decoration as well as for exterior use. For centuries, a particular caste among the Nepalese Newars, called “Silpakar,” has dutifully preserved the country’s woodcarving heritage. Lately, however, peoples of other castes have joined the occupation. Originally supported and encouraged by the Malla kings, the art is now supported primarily through purchases made by Western tourists.

Most Silpakars still engage themselves in various aspects of the woodcarving industry. Silpakars are prominent at Jombahal, in Lalitpur, and out of 700 Silpakar families in Bugmati, 300 operate their own woodcarving shops. Om Krishna Silpakar, 45, the owner of Om Wood Carving at Patan Industrial Estate, belongs to one such family. According to him, the woodcarving industry was monopolized by the men until 15 years ago. Lately, women have strongly shown their skill. Of Krishna’s 22 employees, 6 are women. He claims to prefer women to men because the women tend to remain in the profession longer. He points to Nani Maiya, who has been working with him for 22 years, and Lakshmi Shakya, with him for 20 years. So far, he has been able to train 400 to 500 prentice woodcarvers. He states that the wage of woodworkers ranges between 75 cents to US$5.00 per day, depending on the quality of work. According to Krishna, window prices range between a modest $15 to a profitable $7,000. It is the world-renowned peacock window which fetches maximum returns.

Om Krishna, like most Silpakars, feels an abiding love of and responsibility to his tradition. “I am proud that I have protected the wood carving industry started by my forefathers,” he said. “I have been able to introduce Nepal to some 40 to 50 countries through the exports of my woodwork. This gives me great satisfaction. During my childhood, I would be thrilled when tourists visited. I still remember fondly when King Tribhuvan and Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited our workshop.”

Of late, modern construction has threatened to usurp traditional architecture. Yet the old-style carvings still lure tourists. In an effort to preserve existing ancient works, the Bhaktapur municipality has strictly prohibited the demolition of traditional buildings for replacement with modern ones.

History relates how woodcarving in Nepal developed in Kathmandu Valley largely during the Malla dynasty, which was founded in 1350 by Jayasthiti Malla. The Malla period continued for almost 600 years and was a glorious era in the history of Nepal. Mallas developed trade and commerce, industry, religion and culture. They reached a high level of perfection in the fields of art and architecture. John Sanday in his book Monuments of the Kathmandu Valley writes, “The traditional buildings that are mostly in evidence throughout the valley today represent the craft and architecture of the Malla dynasty, which started in the fourteenth century, survived the early Shah period, but rapidly faded during the Rana era.” The Rana period started in Nepal with the rise of Jang Bahadur Rana in 1846 and the system crumbled down in 1951. One of the reasons why the artistic and architectural activity flourished during the Malla period was that the kings protected such activity. Whatever architecture Nepal has to be proud of today is not from modern construction but solely due to the beautiful art cultivated by the Malla regime.

Today, things are not all favorable for the Nepalese craftsmen. Woodcarvers have their own challenges to overcome. Ramlal Silpakar complains, “The depletion of forests has created a shortage of sal trees, which take at least a hundred years to mature in the forest. It is not within the means of many of the craftsmen to afford the skyrocketing prices of sal wood.” Sita Maiya adds, “Lack of incentive from the side of the state is also a serious problem. In the past, the carving industry prospered because of protection from the state. But now, who cares for the industry?” Ram Bahadur, who has been in carving for generations, states, “We have to stand and make a living on our own. Prospects for training are limited. Many craftsmen families who used to carve wonders have abandoned their craft.” And Shyam Sakya, a prominent woodcarvings businessman says that the domestic market has been whittled down to just the affluent.

A unique success is the Hotel Dwarikas, which is the lifetime achievement of late Dwarika Das Shrestha. The hotel is the manifestation of his effort to restore and preserve a culture and a heritage. Shrestha rescued ancient carvings from demolition sites and commissioned new works from local craftsmen, all of which are maintained and displayed in the hotel, which he created to be a “living museum.” Dwarikas (www.dwarikas.com) is now dynamically managed by Shrestha’s wife, Ambica, who is also the managing director of Kathmandu Travels and Tours.

Dwarika’s is a rare exception. The industry, thought by some to be in trouble, is mainly cushioned by the handicraft centers run by private businessmen. Craftsmen who long ago never had to worry about marketing, are now faced with carving a niche for themselves in the evolving Nepalese economy.

[see also “My Turn” by Dr. Jha.].

CONTACT: OM KRISHNA SILPAKAR, PATAN INDUSTRIAL ESTATE,

LAGANKHEL, LALITPUR, KATHMANDU, NEPAL