By Lakshmy Parameswaran

It all began humbly 25 years ago when Indu Krishnamurthy, affectionately known to friends as Indu Mami, conducted Houston’s first Tyagaraja aradhana (worship). Although that small but charming event was just a short concert meant only to commemorate the musical genius of a great Indian saint, it became an annual event thereafter. And each year it got a little bigger, a little better and a little more significant as a motivating force in keeping alive and moving Westward the great traditions of South Indian classical music. Through the years, that first casual performance grew into a major, three-day festival, celebrated not only in Texas but in many other US cities as well.

On March 28, 29 and 30, 2003, Saint Tyagaraja’s grand silver anniversary at the Sri Meenakshi Temple in Pearland near Houston was–as might be expected–the saint’s greatest Texas party yet. In respect for Tyagaraja’s devotional approach to music, the festive occasion was couched in Hindu religious ceremony and sacred procession, yet it featured quality dance-drama, lots of Tyagaraja’s music and a multi-media play in English on his life.

Saint Tyagaraja had the same impact on the development of Eastern classical music as Bach, Beethoven or Mozart did on the growth of classical music in the West. This 18th century musician (1767-1847) is believed to have composed 24,000 devotional songs, of which only about 700 are in circulation today. Because he was an ardent devotee of Lord Rama, many of his compositions were dedicated to this Hindu God. Tyagaraja lived in Tiruvaiyaru on the banks of the river Cauveri near Tanjore in India. Still today he is honored there every year with a celebration called Tyagaraja Utsavam, which is the model for the Houston annual event.

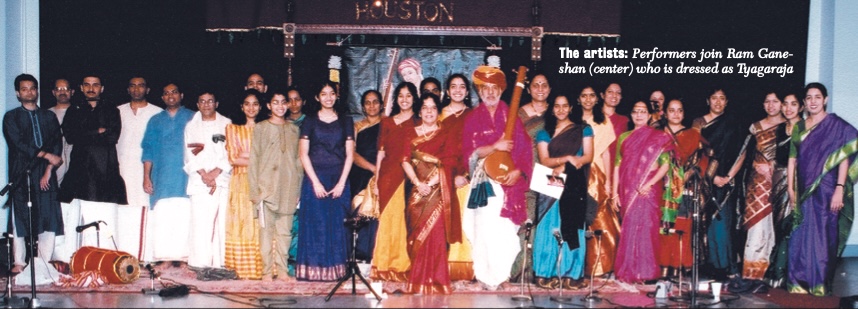

Houston’s celebration began with a joyful parade around the vast Meenakshi temple complex. This procession was meant to exemplify Tyagaraja’s chosen life as a unchavruthi brahmin–a sadhu who wanders, sings and begs for his food. This unchavruthi tradition was common in ancient India where village housewives considered it a privilege to offer such homeless ascetics raw rice and alms. In the Houston event, a fine, locally respected musician named Ram Ganeshan played the part of Tyagaraja and led the early-morning parade, attired as the saint in a flowing turban and carrying the holy man’s signature tambura (a drone stringed instrument).

The end of the procession marked the beginning of the festival’s stage performances, including presentations from more than sixty youngsters. Such a showing of youth was undeniable testimony not only to their talent but–more importantly–to their interest in learning and preserving the ancient classical music of South India.

Some of the youth who participated had been trained only in the Western system of music. To accommodate their interest in Eastern music, Indu Mami transcribed Tyagaraja’s songs into Western staff notation so that they could be “sight-read” by them.

One of the most interesting presentations of the festival was the play about the saint’s life, entitled “The Sands of Thiruvaiyaru,” written in English. Through forty-five songs interspersed with dialogue and scriptural verses, the play emphasized the Saint’s complete devotional self-surrender. His only ambition in life was to become one with his beloved Lord Vishnu, and a fine group of young bharatanatyam dancers from Houston brought this spirit to life beautifully.

Although Tyagaraja simply used music to express devotion, his compositions impacted the evolution of South Indian music in a major way. Hence, the essence of Houston’s Tyagaraja silver anniversary was the singing of his songs. Even connoisseurs acknowledged that the singing was superb. Aruna Sairam, one of India’s current vocal stars, performed the grand finale. Other distinguished performers from India included sisters Ranjani and Gayatri as well as the mother and daughter team of Charumathi and Shubashree Ramachandran.

At the end of the festival, when all was said and done, it was none other than Saint Tyagaraja who had the final word. And, of course, it was sung in song, brimming with devotion: “To all ye great souls, we offer our salutations.”