By Tirtho Banerjee

For the last five years Michael Duffy, a 47-year-old Englishman turned Vaishnava, has brought together eco-awareness and religious consciousness in an effort to revive the lost glory of one of India’s most important pilgrimage towns through an organization called Friends of Vrindavan.

It all started in 1984 when Michael, then a freelance filmmaker, and his photographer wife, Robyn Beeche, came to Vrindavan to make a documentary on India’s colorful Holi festival. After completing the film, the couple went back to London. A subsequent recession in the UK gave them the opportunity to consider working on more projects in India. Setting aside the discouragement of friends, they packed their bags and got ready to leave. Four days before they were to land in India, Robyn got a call from a UK publisher to do a film highlighting the arts and crafts of India. This three-month project helped them transition into Indian life.

Recollects Michael, “After the project ended, I asked myself, ‘What am I going to do now?’ I wanted to do something pragmatic. At that time, I was still in the Western mode of thought–to work and to survive. It took some time to shed that off. Then I decided to go all around India.” He bought a mountain bike and traveled from Bhopal to Orissa and from Kashmir to Chennai to get to know India. The tour helped Michael crystallize his idea about what he would do for Vrindavan. The first thing he did was to organize cycle yatras, which succeeded in raising money. It was from these donations that Friends of Vrindavan took shape.

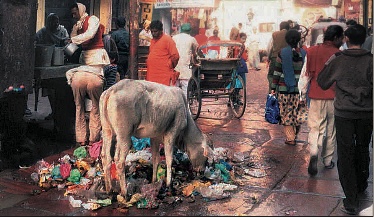

Practical demonstration is the best approach to making a difference, Michael realized, so he formed a small team and started personally cleaning the streets of Vrindavan. They also planted saplings around the city and garnered community support to see them to maturity. It wasn’t easy. It took a lot of effort to convince the locals of the importance of keeping Vrindavan clean. Michael explained to them that devotion to Krishna and reverence for nature are closely connected. This spiritual anchoring helped Friends of Vrindavan to get across their environmental message.

Friends of Vrindavan showed the people that Vrindavan has turned into a prison for its temples. The pungent smell of sewage has replaced the sweet fragrance of sandalwood. The Yamuna has been fouled. So, how do we expect Krishna and Radha to come here and indulge in their divine play? Simply praying to Radha and Krishna but doing nothing to serve the urgent cause of maintaining their earthly playground was contradictory, Michael explained. So, cleaning and greening efforts should become a priority for all Vaishnavas, as their most sacred pilgrimage place was threatened by pollution. Perhaps if we perceive that while worshiping Krishna we are neglecting His beloved land, we must ask ourselves how can we cleanse our hearts through bhajana without fresh water in the Yamuna, clean air and unpolluted food? He asked them, “Can we remember the lilas without the natural landscape and fragrance of Krishna’s stage? How long will we continue to close our eyes and indifferently pretend that we have the vision of a transcendental Vrindavan?”

These questions perturbed the locals and evoked in them a positive response. Slowly and steadily, Michael began to receive public support. The local residents started realizing that any small effort to keep Vrindavan clean and green is a very valuable devotional service, as Lord Krishna and the natural ambience of His home are one and the same.

In the last five years, Friends of Vrindavan has passed many milestones. Recently, it was conferred an award as the best nongovernmental organization in the northern zone by the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department for the stupendous success of its Operation Green program. Under the program, last year Friends of Vrindavan planted 7,500 traditional trees, of which 75 percent have survived. All of the trees were watered by hand. Friends of Vrindavan also undertook greening of the 11-km sacred pilgrimage route around the city as part of Operation Green. Friends of Vrindavan maintains two nurseries with a stock of more than 50,000 saplings. The organization distributes 20,000 tulsi plants free of cost every year.

Friends of Vrindavan has also been removing garbage, including the ever-present piles of plastic, from the temple lands and city lanes. It has constructed five garbage loading ramps in the city to make waste collection easier. Michael’s team makes announcements on loudspeakers discouraging people from dumping garbage in the River Yamuna or illegally on roads and other public places.

Plastics are collected by a special rickshaw and recycled into strong baskets and bags with the help of poor village women and the physically challenged. Ten families are involved in this activity, earning between Rs 100 and 500 for each basket they weave.

Another of Friends of Vrindavan’s unusual feats is the collection of biomedical waste from 45 clinics and hospitals in the greater Mathura-Vrindavan area for mechanized incineration by the Indian Medical Association. At a recent workshop in Lucknow, the chief secretary for environment of the Uttar Pradesh government cited Friends of Vrindavan as creating a biomedical waste management scheme that the entire country could use as an example.

The biggest success story has been the restoration of the five-acre Mansarovar Lake, popularly known as the Lake of Tears. Over the years, water hyacinth choked the lake so much that the surface of the water was completely hidden from view. This drove away the bird life, who could no longer fish here, and starved the water of oxygen. In early 1998, Friends of Vrindavan worked for six weeks to deweed and desilt the lake and plant 1,000 saplings around its border. Now the site is a haven for many exotic birds. Friends of Vrindavan continues to plant more trees each year and asks the visiting devotees to not use detergents or throw plastic bags into the lake.

Michael has been the spirit behind all these encouraging outcomes. However, he’s not satisfied. He remarks, “Local support is there, but that does not translate into action. Besides, corruption in civic departments destroys many initiatives that we undertake. I get frustrated when I see the tardy progress of our projects. We have a plan to augment municipal funds using a geographical information system by which tax would be levied on all buildings in the city which are not covered by the municipality and improve present collection to nearly 100 percent, but district authorities are indifferent to the plan.” A great admirer of Chaitanya, Vivekananda and Mahavir, Michael asserts that religious leaders should follow the footprints of these saints and take responsibility to bring back Vrindavan’s past grandeur.

Michael says that he is happy because “Vrindavan has given me a chance to understand the Hindu religion.” Something about his efforts to clean up the holy city has drawn him closer to Krishna. When he and his wife were returning to Vrindavan from Nepal three years ago, they were separated at the airport due to some document problems. Michael said, “The pain of separation in those hours at the airport helped me surrender to Krishna. I moved into another realm. I realized that Krishna exists.”

Tirtho Banerjee is a freelance writer based in lucknow specializing in indian environmental issuesfor more information visit www.fov.org.uk or e-mail richard@fov.org.uk or gambhira@vsnl.com

MORE PILGRIMS THAN A TEMPLE TOWN CAN HANDLE

STUDY SHOWS HOW PILGRIMAGE SITES CAN’T MANAGE THE PRESENT SURGE OF VISITORS

It’s sad but true: Holy pilgrims to India’s holy sites are creating a wholly unpleasant mess. Several major pilgrimage destinations in India, principally Vrindavan and Tirumala-Tirupati, were the subjects of a study conducted by Kiran Ajit Shinde at the Asian Institute of Technology’s School of Environment, Resources and Development, Thailand, in which environmental degradation due to pressures exerted by an increase of visitors was discussed in detail.

The number of pilgrims, also known as the floating population, often significantly outnumbers the local population, severely compounding issues that plague nearly all of India. Vrindavan is a small town, with a population of 56,000. About two million pilgrims come each year, an average of three times the local population every month. With a local population of less than 50,000, the little hill town of Tirumala hosted over 14 million pilgrims in 2001, an average of nearly 40,000 per day.

These visitors naturally create a demand for supporting infrastructure, such as facilities for accommodation, which causes urban expansion often at the expense of these rural oases’ natural beauty. Increased air pollution and insufficient solid waste disposal only begin to speak of the strain that large pilgrim populations place on small temple towns. When they were founded as remote spiritual sanctuaries, India’s population was less than one percent of what it is today, there was no rail system and the average Indian never ventured more than 50 miles from his home.

In Tirupati the stress and strain caused by this increase is felt with the scarcity of drinking water. The municipality supplies 15 gallons of water per day per person, whereas the standard for human consumption use is 30 gallons. Unauthorized occupation of and encroachment on water tanks, canals and ponds has resulted in depletion of ground water.

The water shortage pales in significance to a sewage network which serves only 55 percent of the total area in Vrindavan. In the remaining areas, septic tanks or open gutters are used, and a mere 16 public toilets exist in the city. The two sewage treatment plants are nonfunctional, and raw sewage goes directly into the Yamuna River.

Both these cities also face air and noise pollution problems. For example, the average width of a street in Vrindavan is seven meters, originally meant for bullock carts. Thus, automobile and pedestrian traffic share the same congested space, and air pollution caused by old diesel-burning vehicles is on the rise.

It doesn’t stop with air and water. Development in Tirumala has caused total denudation of the forests and soil, leading to near extinction of the indigenous flora and fauna. Wildlife has been severely affected by light and noise pollution at night.

Who is responsible? Strategies for better environmental management are only beginning to see the light of day. On the one hand, local authorities are incapable of handling the additional burden of the floating population due to lack of resources and authority to act. On the other hand, most religious institutions, which benefit directly from offerings made by pilgrims, as well as local businesses, are not contributing to improving the environment.

Shinde suggests that these institutions have the moral responsibility of propagating religious faith while incorporating environmental concerns. He argues that pilgrimage needs to be acknowledged as an economic activity which provides income for local residents but also produces output that adds to environmental pollution.

For the long term, Shinde recommends developing policies to manage the impacts–the effects–through cleanup programs such as those spearheaded by Friends of Vrindavan, as well as increasing and improving carrying capacity and waste management. If those measures prove ineffective, he suggests limiting the causes, meaning regulating the influx and flow of pilgrims according to temple carrying capacity, such as has been done at Amarnath.

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES IN PILGRIM TOWNS

Pilgrims in Tirumala-Tirupati offer about 20,000 coconuts per day to be carried away as waste.

Visitors to Tirumala-Tirupati generate 35 tons of waste per day, higher than the per capita in urban areas.

Air pollution in Tirumala-Tirupati is double the maximum permissible for religious places in Andhra Pradesh.

With 12,000 tons of waste accumulated in the Pamba River at Sabarimala, the presence of E. coli has reached near epidemic proportions at 19 times the permissible limit.

Pilgrims in Tirumala-Tirupati offer about 20,000 coconuts per day to be carried away as waste.

Visitors to Tirumala-Tirupati generate 35 tons of waste per day, higher than the per capita in urban areas.

Air pollution in Tirumala-Tirupati is double the maximum permissible for religious places in Andhra Pradesh.

With 12,000 tons of waste accumulated in the Pamba River at Sabarimala, the presence of E. coli has reached near epidemic proportions at 19 times the permissible limit.

STAGGERING NUMBERS DURING BRAHMOTSAVAM MAIN FESTIVAL IN TIRUMALA-TIRUPATI (1998)

Pilgrim transport trips from Tirupati to Tirumala -10,070

Total passengers – 368,029

Heads tonsured – 240,032

Average occupancy at devasthanam (4,216 rooms) – 92.7%

Peak occupancy at devasthanam – 98%

Pilgrims fed with free meals – 212,777

Pilgrims fed with free meals on peak day – 29,799

Pilgrims had darshan – 560,036

Pilgrims had darshan on peak day – 64,117

Pilgrims for sarvadarshan (free) – 392,750

Total collection – US$1,023,000

Hundi collection (offerings in the temple) – US$651,000

Source: Tirumala-Tirupati Devasthanams