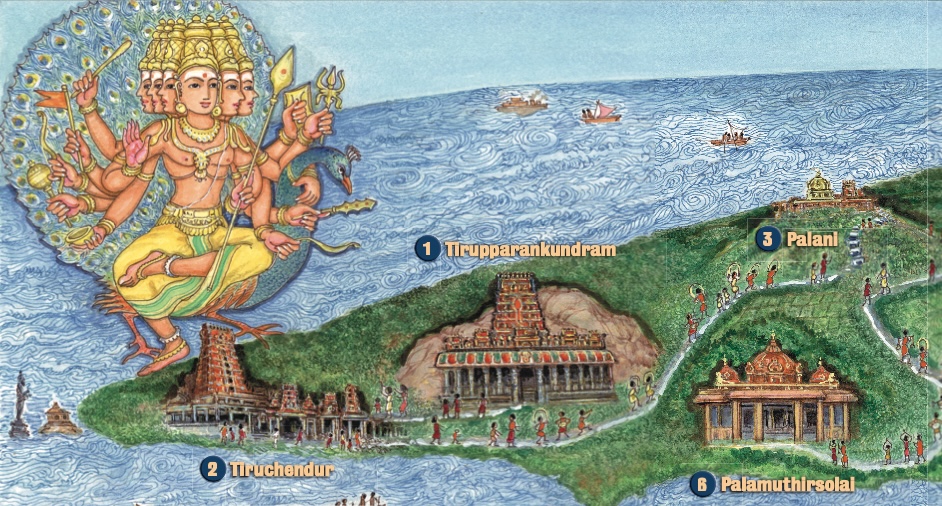

The devotee who seeks the darshan of Lord Murugan, the Tamils’ most beloved God, no doubt finds Him at all of His temples. But those who really want to get Murugan’s attention set out on an unforgettable journey, one both within and without. For those who seek His blessings for the upward climb of kundalini, the aru-pa-dai-vee-du, meaning “six encampments, ” is the pilgrimage of choice. The destinations of this journey are first Tirupparankundram, then Tiruchendur, followed by Palani, Swamimalai, Tiruttani and finally Palamuthirsolai. The fact that this sequence is far from geographically convenient is part of the austerity that comes with any true pilgrimage.

Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, founder of Hinduism Today, sent a number of his monks on this sacred pilgrimage in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. In December, 2006, his successor, Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami, continued the tradition, sending three monks from his Hawaii monastery, including one of the magazine’s editors, to South India for the pilgrimage. This Educational Insight has been developed from their collective experience. It contains spiritual and practical information on the pilgrimage to serve as inspiration for devotees of Lord Murugan to set out upon it and tips for a successful journey.

Skanda, as Murugan is called in the Vedas, was born of a red spark from Supreme God Siva’s third eye. This Deity of the spiritual path is held in highest regard by the Tamil people, who call Him Murugan, meaning “beautiful.” Thousands of His temples dot the landscape of South India and Sri Lanka–and in modern times, everywhere the Tamil people have migrated, including England, Germany, Fiji, Australia, America, Canada, Malaysia and France. Of all the Murugan temples in Tamil Nadu, the six in this pilgrimage are most revered. They were collectively immortalized by Saint Nakkirar in his second-century song Tiru-murug-arru-padai, hailed as one of the most important works of Tamil Sangam literature. And they were given special renown in the songs of saints Arunagirinathar, Kumaraguruparar and other luminaries.

A lyrical narrative, both philosophical and theological, Tirumurugarrupadai was instrumental in propagating Murugan worship in its time. Well known today, it is often sung by devotees as a hymn of protection. Saint Nakkirar enunciates a concept central to the Saiva Siddhanta theology of South India, that in the act of spiritual liberation, God’s initiative is as intense and indispensable as that of the devotee. Nakkirar invokes the grace of Murugan to take the initiative and shower grace upon the seeker who visits His six abodes.

The significance goes beyond Saint Nakkirar’s having woven the temples into his enchanting poem in specified order. There is metaphysical meaning, too. Yogis of yore determined that each temple stimulates a specific chakra in the subtle body of man: Tirupparankundram lights a fire in the muladhara chakra governing memory at the base of the spine. Tiruchendur moves the next chakra, svadhishthana, below the navel, governing reason. Palani animates the manipura chakra of willpower at the solar plexus. Swamimalai spins the heart chakra, anahata, the center of direct cognition. Tiruttani opens the vishuddha chakra of divine love at the throat, and Palamuthirsolai electrifies the third eye of divine sight, ajna chakra.

Nowadays, each temple is thronged by thousands, or tens of thousands, of devotees every day, and many more during annual festivals. Multitudes of sincere seekers of every generation since Nakkirar have wended their way through the life-transforming experience of the arupadaiveedu pilgrimage. At the outset of Tirumurugarrupadai, Nakkirar assures us, “With a heart imbued with love and purity, and a will tuned to do His bidding in virtuous acts, if you seek His abodes, then shall be fulfilled all your cherished desires and objects.”

PAKTHIYAL NAN UNNAI RATNAGIRI

TIRUPPARANKUNDRAM

MOUNT OF BEAUTY

The devotee in search of Lord Murugan’s grace begins the fortnight-long six-temple pilgrimage at Madurai, the famous temple city, an ancient capital of the Pandya kings and hub of South Indian art, literature, architecture and sculpture for millennia. This “Athens of the Orient ” was the seat of the Tamil Sangams, producing some of the finest philosophical treatises and exquisite, heart-melting devotional poetry during a golden age of Tamil civilization.

We arrive in Madurai via a short flight from Chennai, though it is more common to travel the 460 kilometers by overnight train or bus. Driving north into the city from Madurai’s modest airport, the pilgrim is blessed with the sight of Tirupparankundram to the West. This hill, easily seen perched 550 feet above the otherwise flat landscape, is a massive granite rock at which Lord Murugan’s first encampment is situated.

Madurai is given life by the famous Meenakshi-Sundareshvara temple, which lies at its center. This vast citadel, rebuilt by the Nayak kings between the mid-sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries, thrives with the constant bustle of hundreds of thousands of worshipers every day. Lodgings of all grades are abundant in the city, most of them located conveniently near the temple.

Traditionally, the devotee visits a Ganesha shrine at the inception of the aru-padai-veedu pilgrimage. Our Gurudeva advised going to the massive, obstacle-removing Ganesha, called Mukkuruni Vinayagar, inside the Meenakshi-Sundareshvara temple itself. So, after getting settled, we depart for the east entrance of Madurai’s massive temple complex.

Resolving to follow the strictest protocol on our yatra, we go only to the temple’s Ganesha shrine, respectfully resisting the powerful pull to have darshan at the main Siva and Shakti shrines. From this moment on, until the pilgrimage is complete, we will visit no temples or shrines other than the six prescribed Murugan temples. Proceeding to the kodimaram (flagpole) and turning right before the main shrine, we wend our way through the labyrinthine complex and soon stand before the ten-foot-tall murti of Mukkuruni Vinayagar. The priest attending the shrine performs a short arati on our behalf. This is a quiet area, and devotees nearby are meditating on the Lord of Obstacles. Sitting with eyes closed, we beseech His inner assistance with the sacred trek we are about to undertake to His brother’s abodes. Sounds of all kinds overwhelm our ears: priests chanting, bells ringing, votaries singing, children playing and the shuffling feet of countless devotees streaming by as they move from shrine to shrine for darshan.

The first day of our pilgrimage now complete, Lord Murugan’s first abode is on our minds’ horizon. Arising early the next morning, we drive just seven kilometers southwest to Tirupparankundram, a large hill and favorite resort of Murugan, extolled as a mount of beauty in Saint Nakkirar’s poem. In fact, this is where the poet wrote his famous hymn. Ratna Navaratnam tells us in Karttikeya, The Divine Child, “The beautiful setting of this hill with its lotus ponds, trailing carpets of flowers and swarms of bees and water fronts are described in Tirumurugarrupadai, ” which in Tamil means “Holy Guide to Lord Murugan.”

The Tirupparankundram Arulmigu Sri Subrahmanya Swami Tirukkoyil lies at the foot of the hill, on the north side. Entering the temple through the tall, ornately carved and colorful gopuram, we ascend steps leading through pillared halls, rich with sculpture and art, a windfall of being near the central hub of Madurai. We chose Markali, the holiest month of the Tamil calendar, for our pilgrimage. This is the same time when Ayyappaswami devotees from across South India perform their annual yatra to Sabarimalai in Kerala. Many of them follow the strict practice of paying their respects at every temple along the way, so this popular temple is brimming with excited, black- and orange-clad followers of Ayyappaswami.

The entire cave-like shrine, including the murtis, is carved right out of the side of the granite hill. The temple precincts grow tighter and tighter as devotees ascend toward the inner sanctum. Squeezing together with hundreds of others, winding their way through a maze of metal railings designed to keep everyone flowing along in an organized fashion, worshipers arrive at the inner sanctum. We experience an odd juxtaposition of nearness and swiftness in this process. Moving single-file past the shrine, we find ourselves a few feet from Lord Murugan–and for a mere moment, we can almost reach out and touch Him.

Murugan is known as Subrahmanya Swami at Tirupparankundram. Our guide, a boy who attends the temple’s pathashala, explains that this is the famed site where, according to legend, Murugan married Devayanai after defeating the demon Surapadman. This marriage symbolizes the devotee’s uniting with God after transcending his own lower nature. The rock-cut shrine depicts the story of the procession of Gods, seers, men and animals who came to this mount to witness the mystical wedding. Holding His vel, or lance, Murugan is enshrined with Devayanai at His side, as well as Sage Narada, who performed the wedding. Above are the Sun and Moon; below are goats, cocks, elephants and peacocks. There are shrines on either side for Karpaga Vinayagar, Durga, Sivalingam, Perumal (Vishnu), as well as Saint Nakkirar. We are surprised to find that Durga’s shrine is the center-most, intimating that it could have been the original sanctum of the temple.

Our guide informs us that in Murugan’s shrine abhi-shekam is not performed to the main rock-hewn murti, but only to His silver vel. In honor of our visit, the head priest takes hold of Murugan’s vel and performs a brief but powerful abhishekam to it with milk and vibhuti, or holy ash, and then deftly packages the ash and gives it to us to take away as prasadam. Descending the steps as quickly as we came up, we discover a small, pillared hall off to the side that is a perfect place to sit and meditate a while before leaving.

What was initiated here will grow and blossom through the rest of the pilgrimage. The experience burns deeply into our souls, but little prepares us for what we are to experience at Murugan’s seaside abode.

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF TIRUCHENDUR (1)

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF TIRUCHENDUR (2)

TIRUCHENDUR

ABODE OF FULFILLMENT

Deep in the south of Tamil Nadu lies the famed spiritual center called Tiruchendur. Trains and buses ply their way incessantly from Madurai. We take the early morning train to Tirunelveli, and then a 41-km taxi ride to Tiruchendur, winding through the traditional rural landscape, unchanged for centuries. Driving by rice paddies and groves of palmyra and banana, we feel we are journeying back in time.

Pilgrims approach the Arulmigu Sri Subrahmanya Swami Tirukkoyil via a magnificent, covered, open-air walkway that extends 750 meters from the town’s center. It is flanked by an overwhelming menagerie of stalls selling garlands, fruits and other offerings, religious music, colorful cloth and objects for the home shrine. Approaching slowly, we soon spot the temple’s grand, nine-tiered mela gopuram. This white stone tower displaying an enormous blue vel is a striking landmark, visible to sailors from miles away at sea and beckoning devotees from all around. This west entrance, we are told, is only opened during the temple’s annual festival.

Catching the smell of sea air, we know we are near. Exiting the corridor, we take in the full view of the seashore, the temple perched on a gentle slope only a few meters to the left. Here the salty waters of the Gulf of Mannar lap against a broad, sandy beach where pilgrims bathe in the sea before entering the temple. The primary entrance to the temple is here, facing south. Called the Shanmuga Vilasa mandapam, it is an ornately carved, 124-pillar hall standing as a testament to the craftsmanship that prevailed in the era when this temple was built. We are told the temple was originally built of sandstone, thus the name Tiruchendur, “Holy Red City.” When that eroded away, it was rebuilt in granite. Priests are everywhere. We speak with a few in hopes of making arrangements to have darshan of Murugan at tomorrow’s early morning abhishekam.

In the month of Markali, worship begins at Tiruchendur at 3Êam. We arise before dawn and take the short walk to the temple. The dimly lit sanctuary is already crowded with devotees. At 5:30 we are ushered to the ocean-facing main shrine. We are three of fifteen people paying Rs 200 (us$5) for tickets allowing us to sit right before the sanctum.

The granite statue is Bala-su-brah-man-ya-swa-mi, the pious young ascetic. Several paintings in the temple describe the legend: Murugan encamped at Tiruchendur before and after defeating the demon Surapadman and his malevolent band. Kneeling by a small Lingam, He worshiped His Father, Siva, seeking forgiveness for his necessary but regrettable act of killing. Devas arrived in multitudes to thank Murugan for saving them from the demons’ wrath, and He quickly stood up to bless them. It is this position in which the murti was created, holding flowers in one hand and a mala of rudraksha beads in the other, utterly absorbed in adoration of God Siva.

We sit humbly before the Deity, a striking image coated from head to toe with sandalwood paste. The priest deftly removes the fragrant covering and proceeds to pour oil, panchamritam and liter after liter of milk–so much milk, the ablution seems to last an eternity. When milk is poured, this glorious murti turns evenly white all over, revealing details in the dark stone and evoking intense devotion among the priests and devotees. The final ablution is with vibhuti, holy ash. The priest carves out a beaming smile for Murugan in the white coating. This evokes a spectrum of emotions among the devotees–from energetic bhakti to delicate smiles and quiet laughter. We find that this deeply devotional rite has connected us to Murugan in a new way. A half-hour after the puja began, it is complete, and we are quickly ejected back out into the crush of devotees streaming by the shrine for a glimpse of Murugan in the day’s regal attire.

Not far from the main sanctum, we come upon the south-facing shrine of the utsava murti. This bronze image, which is paraded around the temple during festivals, is so bright it looks as if its composition could be mostly gold. We learn from a fascinating collection of paintings displayed in the third prakaram that Dutch invaders arrived in the 17th century and stole the precious murti. Encountering a massive thunderstorm at sea, the plunderers grew fearful, believing their crime had cursed them, and heaved the booty overboard. The Nayak king who patronized the temple at the time instructed his local representative, Vada-ma-lai-appa Pillai, to have a new murti made. In the meantime, Lord Subrahmanyam appeared to Vada-ma-lai-appa in a dream, indicating the exact spot where the murti lay. Men were sent out in ships to recover it. As foretold in the dream, a lime floating in the water and a kite bird flying directly above marked the Deity’s location on the sea floor. Retrieving the murti, they returned it to the temple. But the temple’s hereditary priesthood refused the king’s order to welcome the desecrated image. The king, adamant that the Deity be restored to its respected position, commissioned a separate family of Adisaiva priests to reinstall it and conduct the daily rites. To this day, that same clan of Adisaivas operates the shrine, completely independent of the other shrines and activities at the temple.

One afternoon we visit Nalikkinaru, the fresh-water well only meters from the shore, where Murugan is said to have cleaned His vel. Fed by an underground spring, it never dries up, even in severe drought. The water is believed to heal ailments of all kinds.

On our third day, we rise just before the Sun. Making our way to the temple, we enjoy the morning fragrances as the town awakes and prepares for its day: fresh dosai, hot sambar, sweet rose milk. The bliss permeating this town is amazing. Every time we stop and stand quietly, all we can feel is this sublimity. All here rings with a happy contentedness, a feeling that everything is all right, right now. Perhaps it’s the location at the seaside, the clean air or the presence of the playful child Murugan that lends a sweetness and mellowness to everyone and everything at Tiruchendur.

Hundreds of Ayyappaswami’s pilgrims on their way to Kerala are bathing in the ocean in anticipation of the sun’s imminent rising. A peacock, perched royally atop the gopuram of the Shanmuga Vilasam, calls out. Is he the same one we saw there at dusk last night? Kites circle overhead just offshore, bringing to mind the story of the Dutch and the utsava murti. Devotees are gathered out on the rocks, others on the beach, still others in an open-air mandapam abutting the temple. Cows saunter through the dispersed crowd; pilgrims like us touch them for blessings. Goats and dogs, young and old, and one cat, meander among pilgrims as the rising Sun marks the new day’s beginning.

After darshan of Lord Murugan in the sanctum, we continue our exploration of this cavernous edifice. Vast halls and corridors have been added over centuries. One of the delights is to roam these passageways as the sea breeze blows through. This is a grand temple, a true work of art and devotion in granite. It gets quieter and quieter as ones goes ’round the second prakaram and further out into the third. There are solitary hideaways for private meditation. On the north side of the third prakaram we encounter a shrine for Vishnu carved out of the rock itself, with a monolithic, larger-than-life, reclining murti.

Continuing our pradakshina, we notice two men working quietly inside a small, granite-walled chamber. They are laboriously grinding sandalwood on a big, wet, granite slab, slightly funnel-shaped toward one end to collect the paste.

The use of sandalwood is famous here at Tiruchendur. According to Sivakamasundari Shanmugasundaram, reporting for Hinduism Today in 2002, the temple spends about $150,000 per year for this aromatic, yellowish heartwood. While sandalwood is a primary sacrament used abundantly in Hindu worship, doubtless no other temple in India buys as much of it. Huge amounts are ground fresh daily right here as has been done for millennia. Applied to the Deity during puja, the cooling, fragrant paste is then given as prasadam to devotees who lavishly smear it on their face, arms and body, to soothe, to bless, to heal.

For the 30,000 devotees who visit every day, this ocean-side temple of magic radiates the peace that remains after all desires have been fulfilled. The serenity makes an durable mark in the mind, concealing any hint of the intensity that awaits us at Murugan’s next encampment.

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF PALANI – NATHAVITHUGAL

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF PALANI – VARADAMANINI

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF PALANI – PALANIMALAI

PALANI

MOUNT OF MEDITATION

The most revered of all temples to Lord Murugan is the Arulmigu Sri Dandayuthapani Swami Tirukkoyil at Palani. This third abode is 137 km northwest from Madurai, and reached via Madurai by train, bus or car. The countryside here has a pre-historic feel to it–lone, worn hills that rise abruptly from the ground like rough-hewn tortoises. At any time of year, devotees are seen walking alongside the roads leading to Palani. Carrying only a small yellow bundle of necessities, they undertake this difficult trek, coming from all over South India. As we near Palani, the temple comes into focus at the top of the rounded hill, a verdant mountain range in its background. Accommodations are simple here, even austere. The temple deva-stha-nam runs a huge hostelry near the temple steps, and there are private hotels and lodges in town.

We are excited to arrive at Palani. While Murugan in any form is dear to Saivite monks, here He appears as the loincloth-clad renunciate, called Danda-yutha-pani-swami. Palani means “You are the fruit, ” an allusion to a tale in which Murugan learned that He is the fruit of wisdom of the sages.

After settling in, we meet our guide, Mr. M. Muthumanickam, a member of the government endowment board that administrates the temple. He takes us by auto-rickshaw to the bottom of the hill, where a road circuits the hill. Muthumanickam informs us that circumambulation of the hill is best done in the early morning or at twilight. It is now late in the afternoon, and we are eager to get to the temple. So, we worship briefly at the Vinayagar shrine and ardently climb the 697 steep, stone steps that zig-zag their way to the top. On subsequent visits, we explore the other ways provided to ascend the hill–rope car, winch trolley and an alternate, less steep pathway built for the temple elephant which is also used by children and the elderly.

At the top, the steps give way to a wide, paved walkway surrounding the temple. Muthumanickam tells us, “It is traditional to go around three times.” This pradakshina gives pilgrims an opportunity to leave their journey behind and attune their minds to Lord Murugan before entering the temple. Wending our way through endless lines of devotees, passing through stainless steel gates and countless barriers, we arrive just outside the inner sanctum. We pay for special tickets to gain direct access to the shrine. Minutes later we are ushered in front of Lord Murugan for darshan.

The unique murti here was created by Bhogar Rishi, one of the eighteen siddhars of Saiva tradition. He formed the image centuries ago from an amalgam of nine herbs and minerals. Abhishekam is the most important form of worship at Palani–the Deity is bathed six times a day. Muthumanickam relates, “These abundant ablutions over hundreds of years slowly deteriorated the murti. Sixty years ago the temple administration stopped all worship to the original murti and had a bronze replica installed directly in front of it for bathing.” In 2006, R. Selvanathan, Chief Executive Sthapati of Sri Vaithiyanatha Sthapati Associates, Chennai, was commissioned to perform the delicate and complex task of restoring the ancient image. Sthapati explains, “The murti was found to be infirm and unstable, presenting a frail appearance. Body parts were in a very dilapidated condition and may have broken up any moment if not attended to.” Selvanathan’s repair work was successful, and ablutions to the original murti resumed.

Watching the puja is like watching an intricate dance. While only Adisaiva priests enter the inner sanctum, a clan of pandaram priests serves in the preparation of all offerings. Everything passes through their hands before being presented: abhishekam ingredients, clothing, garlands, food, incense and all the lamps. Every priest is dressed impeccably, his spotless veshti wrapped just right. Traditional Sanskrit Vedic mantras are chanted in the inner sanctum, but we hear a priest chant Murugan’s 108 names in Tamil over a PA system. We later see a sign near the shrine stating that, according to the requirements of the temple endowment board, archanas will be performed in Tamil upon request.

While the Deity is being dressed, the crowd’s anticipation grows. Behind us hundreds are chanting, singing, praying. When the curtain finally opens, Murugan is adorned in raja alankaram, dressed like a king–so majestic, so magnetic. A cacophony of sounds envelopes us as the arati swoops past and priests smear vibhuti on the forehead of each one present.

Inside the temple, we notice that a significant amount of renovation work has occurred since our 2004 visit. Particularly evident is the polished granite tile on the floors and walls inside and around the temple. The temple’s most recent kumbhabhishekam was on April 3, 2005. Former Joint Commissioner of the temple, Mr. D. Sundaram, reports, “The renovation work started on March 9, 2005, and finished on March 29. Amazingly, the task was performed by 1,000 workers per shift, three shifts per day. New mandapams in the first prakaram and all the granite floor and wall tile work was completed in just twenty days.”

Muthumanickam informs us that Palani has the highest income of any temple in Tamil Nadu and is second in all of India only to Tirupati’s Venkateswara temple. That doesn’t count the enormous sums of money devotees spend in town on supplies–milk, yogurt, honey, ghee, vibhuti–which they bring to the temple in huge quantities for the daily abhishekams. He amplifies, “There is so much money, more than we can use here. We donate the rest to many of the poorer temples in Tamil Nadu–just enough to each one to keep the basic practices of lighting lamps and simple, daily puja going.” One of the ways in which Palani’s wealth manifests is in its cleaning program. There are workers collecting trash and sweeping and spraying down the walkways all through the day. They set a great example for other temples to follow.

Sunset is nearing. Muthumanickam urges us to stay for the night-time golden chariot procession. We sit down to talk near the Ganesha shrine as the crowds gather. Nakkirar names the third padai-veedu, Avinankudi, and frequently it is said that this temple near the base of the hill is the true abode of Lord Murugan. We ask Muthumanickam about this, and he quickly dismisses the misconception: “The two are really to be considered one temple. They come under the same management and share the same priesthood. It is customary to visit there before coming up the hill to worship here.”

By 7 pm nearly 100,000 people have amassed atop the hill. The devotion reaches a crescendo as the doors of the chariot shed are flung open. Accompanied by nadaswaram and tavil, the chariot begins to roll. This small, ornate carriage and the utsava murti that rides in it are solid gold. A company of police officers with guns and a set of wooden barriers surrounds the chariot from the moment the shed doors are opened until they are locked again. Devotees pay Rs 1,000 (us$25) for the privilege of going inside the barrier to more intimately worship the murti.

The shrine to Bhogar Rishi in the southwest corridor provides a serene and quiet sanctuary in this bustling complex. Very much like a cave, it is a great place for quiet meditation. Introspective devotees can be seen here throughout the day, absorbed within themselves.

The temple’s magic is potent, its vibration ever powerful. So many are captured by Palani. By what seems only to be grace they appear in front of the Deity. They watch an abhishekam and have an archana performed. An arati is passed. The priests put a garland from Murugan around pilgrims’ necks and smear vibhuti on their foreheads, and they go away transfixed. Even if they go to no other temple, their lives are transformed by the Lord of Palani in that single moment.

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF SWAMIMALAI

SWAMIMALAI

ABODE OF THE GURU

Riding on the intensity of Palani, we prepare ourselves for the serene rapture of Murugan’s fourth abode. Known in ancient days as Tiruveragam, the wooded village of Swamimalai is located five kilometers west of Kumbakonam on the banks of a tributary of the Kaveri River. We drive to Trichy, then take the train to Kumbakonam. Accommodations in Swamimalai are almost nonexistent, so it is best to stay in Kumbakonam or Tanjavur (32 km away) and take a bus or hired car to Swamimalai for the day.

The Arulmigu Sri Swaminatha Swami Tirukkoyil is a small, well-maintained temple rising to 60 feet on an artificial hillock constructed from granite stones. One enters from the south or east side and arrives within the third prakaram, at ground level. A thick, high wall protects the complex from the sounds and vibrations of the outside world. Here there are shrines to God Siva as Sundareswarar and Shakti as the Goddess Meenakshi.

After circumambulating in the third prakaram, we ascend the steep steps to the second prakaram. Other than a family of green parrots who enjoy the temple’s outer precincts, this is a quiet, austere place. There is a small mandapam on the east side dedicated to Saint Arunagirinathar and the Tiruppugal he sang in devotional wonder of Murugan. This small open-air pavilion, situated directly underneath the kodimaram, or temple flagpole, is a wonderful place for undisturbed meditation.

Another flight of steps leads to the kodimaram and Vinayagar shrine. There are sixty steps in all, representing the sixty-year cycle of the Hindu calendar. This cycle is based on the planet Jupiter, symbol of the guru in Hindu astrology. This is especially significant at Swamimalai, as it is here that Murugan is the guru, known as Swaminathan.

The first prakaram is enclosed, giving us the feeling of being in a cave. Only small openings vent the abundant camphor and homa smoke. Deities line the north wall. A glorious, silver-clad shrine for the utsava murti draws almost as much attention as the main sanctum.

Instead of Murugan’s usual peacock, we are surprised to find an elephant vahana facing the main shrine. The priest who was our guide, Sivasri P. Ganesa Gurukkal, senses our wondering and explains, “Swaminathan rides Indra’s elephant.” As the story goes, Indra, the King of Gods, left behind His white elephant when He stopped here to worship Murugan.

From here devotees ascend a few steps and pass through a brass-covered doorway onto a raised platform for standing darshan. There is room for many to stand, but those who pay are allowed to sit directly in front of the sanctum on a marble floor during the puja.

With hair in topknot and a large preceptor’s danda in hand, the black stone murti is a full six feet tall. It is dark inside the shrine, but the power of the guru can be felt like an outpouring of love and wisdom. An abhishekam begins just as we sit down. Oil, a mixture of herbs, spices and water called kootu, abundant milk, yogurt and sandalwood paste are poured over the life-size murti in rapid succession.

The sandalwood is mixed to such a smooth consistency that it covers the body thickly and remains like a coat of amber paint. The priest then draws eyebrows, eyes and mouth on the face. He performs a prolonged arati. Passing the lamp before Murugan with steady deliberation, he lingers now and again to allow us all to see the murti’s refined features. Accented by the yellow sandalwood and illumined by the delicate flame, Murugan’s form draws us into rapt attention. Time stands still. Swaminathan is then rinsed, and the panchamritam and vibhuti are poured. The curtain is closed longer than usual while the Deity and shrine are meticulously cleaned and fresh white clothing and a silver crown and kavacham (ornate metal covering) for hands and feet are put on. A priest pours oil onto and then speedily lights the huge alankara dipam, a multi-tiered lamp with 108 wicks. Suddenly one priest throws the curtain open and a second offers the lamp amidst a flurry of chanting, then quickly passes it back out of the shrine where a helper puts it out with a few deft waves of the hand.

After the head priest offers a multitude of other lamps, mudras and mantras, he performs the final arati. The priests take off the murti gigantic garlands that have been offered throughout the day and give them to devotees. As this evening abhishekam finishes, everyone feels copiously blessed.

Escorting the three of us around a profusion of subsidiary shrines, Ganesa Gurukkal proudly declares, “As Adisaivas, we maintain the tradition of chanting only Sanskrit inside the sannadhi (sanctum).” He is referring to the modern-day trend, followed in less strict temples, of performing entire pujas in the Tamil language. He is also emphasizing the special importance of Sanskrit chants at this temple.

According to Ratna Navaratnam, the brahmin priests at Swamimalai traditionally chant Murugan’s six-lettered Sanskrit mantra, “Sa-ra-va-na-bha-va, ” during long periods of meditative japa. She observes that Swamimalai is linked to the anahata chakra, the heart center, which powers the faculties of direct cognition and comprehension. Here, the aspirant attains a mountaintop consciousness: an objective apprehension of the whole of existence. In a split second, complete knowledge of a subject may be known, directly as a boon and blessing from Murugan. Navaratnam writes of the metaphysics behind the relationship of Murugan’s six temples to the chakras, “The chanting of the mystical letters of spiritual potency is the propelling force of an inward spiritual pilgrimage in the form of an introspective meditation. The focal point of meditation is said to undergo a shifting process from the lower centers to the highest center, passing through six stages. These six stages can be taken to symbolically represent the six abodes of Murugan in Tirumurugarrupadai.”

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF TIRUTTANI

TIRUTTANAI

ABODE OF PEACE

Situated 700 feet above sea level amidst a hill range with a dramatic panoramic view is the Tiruttani Arulmigu Sri Subrahmanya Swami Tirukkoyil, Murugan’s fifth abode. From Swamimalai, the pilgrim usually goes to Trichy, the hub for traveling north to Chennai by bus, train or plane. Tiruttani is a small town located 84 km west of Chennai, 13 km north of Arakonam on the Chennai-Mumbai route. There are basic pilgrim accommodations in Tiruttani, but many choose to stay at Chennai or Kanchipuram (40 km to the south), making a day trip to Tiruttani.

The hill at Tiruttani is known as Tanigaimalai, meaning “peaceful hill.” The name refers to the legend of Lord Murugan’s choosing this place for peace of mind and quiet relaxation after defeating Surapadman and marrying Devayanai. But there is much more significance to His presence here.

The ode in Tirumurugarrupadai calls this place Kunrutoradal and describes Murugan as Ceyon, the “Red God ” who loves to sport in the hills. Ratna Navaratnam writes of the ancient tribals and their worship here: “The worship of Murugan takes the form of a dance known as veriyadal in the hilly and forest regions. These highlanders celebrated God Murugan as their guardian Deity and believed that the welfare of their tribe was His concern.” The hill folk, in long, night-draped dances fueled by honey wine, sought to bring the whole tribe into Murugan’s aura, much as the Vedic priests of the North imbibed soma to plunge into a vision-quest of Skanda. Navaratnam explains that they used dance and music to propitiate Murugan for practical assistance, such as to heal disease or alleviate famine or drought. These tribal dance forms are incorporated into today’s kavadi (milk-pot-carrying penance to Murugan) processions celebrated worldwide.

This abode of Murugan is also the birthplace of India’s first vice-president and second president, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan. Yet, it holds even more legendary significance. According to Murugan bhaktar Patrick Harrigan, a host of Gods, saints and sages are known to have worshiped Lord Subrahmanyam here, including Rama, Arjuna, Vishnu, Sage Agastiyar, Saint Arunagirinathar, Saint Ramalinga Swamigal and Sri Muttuswami Deekshitar.

Arriving at the bottom of the hill, we encounter the enchanting Saravana Poigai. Our priest and guide, Sivasri K.V. Ravi Gurukkal, tells us, “This tank is renowned for its sacred water which is known to have healing effects for both bodily and mental illnesses.” After bathing our feet, we turn and ascend the hill via 365 steps, representing the days of the year.

At the top, it is cool and quiet, and one immediately understands why Murugan chose this place for solace. Here it is easy to view the world below from a mountaintop consciousness. A new perspective is gained. In Tiruttani’s setting, the vishuddha chakra is amplified–the unadulterated energy of cosmic love. When there is an inexpressible love and kinship with mankind and all life forms, our consciousness resides in this chakra at the throat. When deeply immersed in this state, there is no consciousness of a physical body, of being a person with emotions or intellect. One just is the light flowing through all form. Ineffable bliss permeates the subtle nerve system as the truth of the oneness of the universe is fully and powerfully realized.

Ascending the final steps to the east entrance, we again encounter Indra’s white elephant where one would expect to see Lord Murugan’s peacock mount. In an even more unusual twist, the elephant faces east, away from the shrine. T.G.S. Balaram Iyer, in his book South Temples, offers, “Some consider that the Lord is ever ready to start on His carrier and rush to the aid of devotees “–meaning the elephant would not even have to turn around to begin a campaign.

Ravi Gurukkal takes us aside to tell more about the temple and its priesthood. There are 27 Adisaiva families serving the temple. He proudly explained, “We follow a strict discipline here. When it is a priest’s turn to do the puja, he must fast, bathe in a designated place inside the temple, then meditate in front of the shrine. Only then can he go inside the sanctum and do the puja.” This sadhana clearly has an effect, as we found them all so humble and content, quiet and composed.

As the puja begins, we are once again captured by Lord Subrahmanyam. Unlike most temple protocols, all offerings except the abhishekam itself are made from outside the shrine, right in front of us. There is something exceptionally sweet about the ritual here: the priests are unhurried and unusually present. Performing the sacred rites is, for these priests, a delightful dance of divine communion, as it was for the tribals of ancient times

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN OF PALAMUTHIRSOLAI

PALAMUTHIRSOLAI

GROVE OF GRACE

The last leg of our pilgrimage returns us to Madurai, the nearest town to Palamuthirsolai, “grove of ripe fruit.” Trains, buses and flights go daily from Chennai back to Madurai. Once there, it is best to hire a car to get to the Palamuthirsolai Arulmigu Sri Subrahmanya Swami Tirukkoyil. Located 19 km north of the temple city in the Alagar Hills above the Alagarkoil of Lord Vishnu, it is the most remote and spartan of the arupadaiveedu.

As we drive through the entry gate and head up the winding road, we are quickly enveloped in the clean, cool air of the thick forest. Soon we arrive at Lord Murugan’s sixth and final encampment. Says Vellayapettai Radhakrishnan for Murugan.org, “While this temple is not as large or bustling as the other five recognized shrines, it is just as incredible to visit. Even today the place is very fertile with many trees and different flora and fauna, a standing testimony to the vivid description of its natural beauty as found in Tirumurugarrupadai.” Though tranquil, the environs here are permeated with an electrical shakti that feels, to us, like an approaching lightening storm.

There is a powerful sacredness here, owing to the three things the temple is famous for: a small stone vel; a Java Plum tree where Saint Auvaiyar met Lord Murugan; and a spring hailed in Saint Nakkirar’s poem as the source of Murugan’s grace on Earth.

Our guide is Sivasri Muthukumara Gurukkal, son of the chief priest. He tells us that, while the importance of this spot has been hailed for centuries, the temple that stands here now was constructed recently. “In ancient times, the vel was worshiped as the main Deity, ” he explains, as he takes us to a shrine holding a stone vel just to the right of the main sanctum. “This vel is of great significance. It is the original Deity, and it is still highly venerated.” The lancelike vel wielded by Lord Karttikeya embodies discrimination and spiritual insight. Our Gurudeva, Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, wrote about the importance of Murugan’s vel in the lives of seekers on the spiritual path: “The shakti power of the vel, the eminent, intricate power of righteousness over wrongdoing, conquers confusion within the realms below. The holy vel, that when thrown always hits its mark and of itself returns to Karttikeya’s mighty hand, rewards us when righteousness prevails and becomes the kundalini serpent’s unleashed power thwarting our every effort with punishing remorse when we transgress dharma’s law. Thus, the holy vel is our release from ignorance into knowledge, our release from vanity into modesty, our release from sinfulness into purity through tapas. When we perform penance and beseech His blessing, this merciful God hurls His vel into the astral plane, piercing discordant sounds, colors and shapes, removing the mind’s darkness.” Pilgrimage is a penance of sorts, and the power of Murugan’s vel is felt throughout the arupadaiveedu. It is a force of change that remains with us, feeding and enriching our spiritual life for years to come.

The Java Plum tree (Syzygium cumini or jambu) at Palamuthirsolai is the tree where Auvaiyar, a ninth-century saint, encountered Lord Balasubrahmanyam. The classic story relates that the elder woman sat under the shade of this tree to rest on the way to the temple. A boy called out from the branches above and asked her if she would like some hot or cold fruit. Perplexed but curious, she asked for the former. The boy shook the tree, and some of the grape-sized plums fell from its branches onto the sand below. Picking one up, she blew on it to clean off the sand. The boy chortled and asked if she was blowing on the fruit because it was too hot. Only when she entered the temple did she realize that she had just met Lord Murugan Himself, and that she actually didn’t know as much as she thought she did. Through His simple play, Murugan shattered her arrogance. Auvaiyar went on to write some of the sweetest, most celebrated Tamil devotional songs. It is considered a miracle that this tree fruits every year during the six-day Skanda Shashthi festival in October-November, completely off season.

To Saint Nakkirar, the spring above Palamuthirsolai is the waterfall of grace that showers the devotee who reaches the final stop on this profound inner odyssey. The water from this spring is said to have healing qualities. Devotees flock there, filling up bottles to take home with them, bringing them first to the temple for blessings.

Today, the central shrine houses a small, standing murti of Lord Murugan, with consorts Valli and Devayanai at His sides. As we sit watching the abhishekam, the image of Lord Murugan’s grace as the waterfall comes to the mind’s eye. The joy of completion pours over us. Inwardly quiet, blissfully content, we feel we have accomplished something special. It is an inner fulfillment, arrived at after an outer journey.

For centuries, seekers who have performed this noble pilgrimage have testified that at its end awaits a release from the worries and concerns of their lives. They are relieved of things long burdening their hearts and minds, never to be plagued by them again. This real-life purifying experience is captured in the Vedas, which affirm, “To such a one who has his stains wiped away, the venerable Sanatkumara shows the further shore of darkness. Him they call Skanda.

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN – TIRUVANAIKA

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN – TOLLUMADA

PRAISE TO LORD MURUGAN WHO RIDES THE PEACOCK