BY GUY BECK

From the chanting of ancient Vedic hymns to the melodic bhajans of modern-day devotees, Indian music is ultimately rooted in basic theological principles of sacred sound. These primordial principles are documented in Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas and Upanishads (ca 4000-1000 bce)–which are regarded as eternal and authorless, though later committed to written form.

Music, both vocal and instrumental, is considered to be of divine origin and is closely identified with the Hindu Gods and Goddesses. The Goddess Sarasvati, depicted with vina in hand, is venerated by all students and performers of Indian music as the divine patron of music and learning; indeed, She personifies the power of sound and speech. Lord Brahma, creator of the universe, portrayed as playing the hand cymbals, fashioned Indian music out of the verses of the Sama Veda. Lord Vishnu, the Preserver, sounds the conch shell, and in His avatara Krishna He plays the flute. Lord Siva Nataraja plays the damaru drum during the dance of creation.

Each of these instruments symbolizes Nada-Brahman–the sacred, primeval, eternal sound, represented by the syllable Om, which generates the universe. This sound is embodied in the Vedas and itself symbolizes Brahman, the Supreme Absolute of the Upanishads. Nada-Brahman appears in musical treatises as the foundation of music. Yoga texts use the term to denote the musical and inner sounds heard in deep yogic meditation. Nada refers to the cosmic sound, which may be either unmanifest or manifest. Since Brahman pervades the entire universe, including the human soul, the concept of sacred sound as Nada-Brahman expresses the connection between the human realm and the divine. Combining the principles of Nada-Brahman with Indian aesthetics of rasa and the structures of raga and tala, the various gharanas have nurtured the formal classical traditions of music to the present day

Nada-Yoga, the yogic discipline that seeks transcendental inner awareness of Nada-Brahman, has also influenced Indian traditions of chant and music. Nada-Yoga techniques, including Om meditation, are found in philosophical yoga texts such as the Yoga Upanishads and the major hatha yoga texts, as well as Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra and its commentaries. My 1993 book, Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, deals extensively with the Hindu philosophies of sound and Nada-Brahman http:/www.sc.edu/uscpress/1993older/9855.html [http:/www.sc.edu/uscpress/1993older/9855.html].

It begins with Vedic chanting

Intrinsic to the ancient Vedic practice of fire sacrifice are chanting and meditation on sound. Recitation and chanting in Sanskrit are traceable to the Vedic period, when the Rig Veda was recited by priests during public and private fire ceremonies. From those early times, chanting has been seen as a powerful means to interact with the cosmos and obtain spiritual merit that would help one to gain a heavenly afterlife or an auspicious next life.

Special brahmin priests known as Hotri chanted selected verses from the Rig Veda in roughly three tones, notated in early manuscripts as accents on particular syllables: anudatta (grave, “not raised “), svarita (circumflex, “sounded “) and udatta (acute, “raised “). The grammarian Panini (4th century bce), who knew the early tradition, described the svarita tone as connecting the other two. But according to modern scholars–and in modern practice–the udatta, left unmarked, is considered the tonic, the principal note upon which the chants are intoned (like middle C); the anudatta, often marked with an underline, is a whole step below (B-flat); and the svarita, marked with a small vertical line above the syllable, is a half step above (D-flat).

Sama Veda chanting

The chanting and hearing of sustained musical notes has been linked to the Divine in Hinduism from early Vedic times. The Sama Veda contains Vedic verses set to pre-existent melodies. These songs, known as samans, were chanted by special brahmin priests called Udgatri during elaborate sacrificial ceremonies to petition and praise the Deities that control the forces of the universe. Unlike the three-tone chanting of the Rig Veda, samans were rendered in melodies of up to seven tones, ranging from F above middle C to G below. These notes were in descending order, as the melodies of the samans were usually descending in contour.

A unique feature of the Sama Veda chanting was the insertion of a number of seemingly ‘meaningless’ words or syllables (stobha) for musical and lyrical effect, such as o, hau, hoyi, va, etc. These stobha syllables were extended vocally, with long duration, on various notes of the Sama Veda scale for the purpose of invoking the Gods. Vedic scholar G.U. Thite explains, “The poet-singers call, invoke, invite the Gods with the help of musical elements. In so doing they seem to be aware of the magnetic power of music, and therefore they seem to be using that power in calling the Gods.” Thite elaborates, “Gods are fond of music. They like music and enjoy it. The poet-singers sing and praise the Gods with the intention that the Gods may be pleased thereby, and having become pleased they may grant gifts.” He stresses the importance of the singing of samans: “Without it, no sacrifice can go to the Gods.”

Precise methods of singing the samans were established and preserved by three different schools–the Kauthumas, Ranayaniyas and the Jaiminiyas, the oldest. Each has maintained a distinct style with regard to vowel prolongation, interpolation and repetition of stobha, meter, phonetics and the number of notes in scales. In each school there has been a fervent regard for maintaining continuity in Sama Veda singing to avoid misuse or modification over the years. Since written texts were not used in early times–were in fact prohibited—the priests memorized the chants with the aid of accents and melodies, passing this tradition down orally from one generation to the next for over three thousand years.

Evolution of Gandharva Sangita

The early tradition of saman singing set the stage for the creation and development of Indian classical music known first as Gan-dharva Sangita, then as simply Sangita. According to Dr. V. Raghavan, Sangita is born from the Sama Veda: “Our music tradition in the North, as well as in the South, remembers and cherishes its origin in the Sama Veda, the musical version of the Rig Veda.” Indian music, known as Sangita, has three divisions, as understood from the musical texts: vocal music, instrumental music and dance. All three have always been intertwined, whether in religious observances, sacred dramas or courtly entertainment.

Gandharva Sangita ( “celestial music “) was considered to be similar to the music performed and enjoyed in Lord Indra’s court in heaven. Though primarily vocal, this ancient religious music included instruments such as the vina, flutes, drums and cymbals, as mentioned in Vedic literature. In fact, the vina was played during Vedic rites by the wife of the officiant. The celestial performers of the music were the Gandharvas, a class of male demigod singers who resided in heaven. They were accompanied by their wives, the dancing Apsaras, and by the Kinnaras on musical instruments. Each of these arts–vocal music, instrumental music and dance–was thus considered divine. The leader of the Gandharvas was Narada Rishi, the son of Brahma and author of seven hymns in the Rig Veda (and Sama Veda). He was also said to be the inventor of the vina and the sage who instructed human beings in Gandharva Sangita, having learned it from Goddess Sarasvati Herself.

Sangita’s musical scale–used first in Gandharva Sangita and later in all other types of Indian music–differs from the Sama Veda scale described above. Sangita uses a seven-note system (sapta-svara) in ascending order. Current today, the standardized notes are sa-ri-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni-sa, taking their sounds from the names of different birds and animals: sadja, peacock; rishabha, bull; gandhara, ram; ma-dhyama, crane; panchama, cuckoo; dhaivata, horse; and nishada, elephant). These are set forth in the Narada Siksha (1st century ce), where the presumed author, Narada Rishi, explains how these seven notes were determined from the three Vedic accents: udatta into Ni and Ga, anudatta into Ri and Dha, and svarita into Sa, Ma and Pa.

Complex rules and standards for scales, rhythms and instrumental styles of Gan-dharva music were gradually codified in a number of texts which came to be known collectively as the Gandharva Veda, an auxiliary text attached to the Sama Veda. Several of these works have been lost; but the oldest surviving texts of Indian music–the Natya Shastra by Bharata Muni and the Dattilam by Dattila (both ca. 200 bce) and the aforementioned Narada Siksha–provide glimpses into the evolution of Gandharva Sangita. Bharata’s work in particular was foundational. It was he who classified musical instruments into four categories based on the Gandharva instruments: vina (chordophones), drum (membranophones), flute (aerophones) and cymbals (idiophones). Based on these four divisions (given in parentheses), the famous Sachs-Hornbostel system–used today in the academic field of ethnomusicology–was established in the early twentieth century. Also, the term raga ( “musical mood or flavor “) as a type of scale or melodic formula, first mentioned in the Narada Siksha, was derived from the parent jati enumerated in Bharata’s work.

Gandharva music soon developed into the principal style of music performed in Hindu festivals, court ceremonies and temple rituals in honor of the great Gods and Goddesses, like Siva, Vishnu, Brahma, Ganesha and Devi. The ancient epics and Puranas describe temple musicians and dancers who performed for the pleasure of these Deities and contain numerous references to temple music in ancient times. Music was also associated with sacred dramatic performances-, as clearly evidenced in Bharata’s Natya Shastra.

Evolving vernaculars

Special songs used to propitiate the Gods, called Dhruva, were rendered not in Sanskrit but in Prakrit, a derivative language with less rigid grammatical construction, which led to the evolution of several vernaculars. The Dhruva form was the prototype of the medieval Prabandha, from which arose the classical devotional forms sung in vernacular and known as Dhrupad (Dhruvapad) in the North and Kriti in the South. The rapidly developing music of India also enlarged itself with materials from outside the original repertoire.

Nada-Brahman

By the period of the early Bhakti movements in South India (7th to 10th centuries ce), Indian musicological treatises such as Matanga’s Brihaddeshi began to incorporate the theory of sacred sound as Nada-Brahman, the principles of Nada-Yoga and the Tantra traditions, interpreting all music as a direct manifestation of Nada-Brahman–and therefore as a means of access to the highest spiritual realities. Music was viewed not only as entertainment but as a personal vehicle toward moksha, liberation.

Subsequent musicological authors influenced by Matanga discussed Nada-Brahman in relation to the Gods and as present throughout the cosmos, including all living beings. For example, the Sangita Ratnakara of Sarngadeva (ca. 1200-1250 ce), arguably the most important musicological treatise of India, opens with the salutation: “We worship Nada-Brahman, that incomparable bliss which is immanent in all the creatures as intelligence and is manifest in the phenomena of this universe. Indeed, through the worship of Nada-Brahman are worshiped Gods (like) Brahma, Vishnu and Siva, since they essentially are one with it.” Thus by this time there was a full conflation of the tradition of sacred sound (the Nada-Brahman principle) with the art of music in all its phases, including religious, secular, classical and folk.

Bhakti-Sangita

Celebrated by many as a distinct doctrine and mode of religious life superior to jnana (knowledge) and karma (works), bhakti–initially propounded in the Bhagavad Gita by Krishna–became the primary motive for religious music from the early medieval period. As early as the sixth century ce in South India, bhakti emerged as a powerful force that favored a devotion-centered Hinduism, with songs composed not only in Sanskrit but in vernacular languages. Leading this trend were two main groups of poet–singer–saints in South India whose devotion to Siva and Vishnu lives to this day: the Saivite Nayanars and the Vaishnava Alvars. The collections of their devotional poetry in Tamil–the Saivite Tevaram and the Vaishnavite Naliyar Prabandham–represent the oldest surviving verses in Indian vernaculars. These two books are the first hymnals of Bhakti-Sangita or devotional music.

Directly related to the word bhakti and to Bhagavan (a word for Supreme Being) is the term bhajan, which means musical worship. These three words arise from a single Sanskrit root: bhaj, “to share, to partake of ” (as in a ritual). Bhagavan refers to the Lord who possesses bhaga, good fortune and opulence. Bhajan, a somewhat generic term for religious or devotional music other than Vedic chant and Gandharva Sangita, is directly linked to the rising Bhakti movements. In bhajan, God (Bhagavan) is praised, worshiped or supplicated in a mutual exchange of loving affection, or bhakti. The Bhakti traditions contained various styles of bhajan or Bhakti-Sangita, ranging from formal temple music to informal group or solo songs. Hindu music incorporated a simple aesthetic, reflecting back to these emerging Bhakti movements and their perspectives on music as a means of immediate communion with a chosen Deity.

The Upanishads describe Brahman, the Supreme Truth, as full of bliss and rasa ( “emotional taste, pleasure “). In theistic Vedanta, Brahman as supreme personal Deity–whether worshiped as Vishnu, Siva, Sakti or in any other form–was believed to be the source of all rasa and extremely fond of music. The emotional experience produced by music in the minds of the listeners (bhava) was thus also linked to God.

Raga and tala

It is said that the musical scales or melody formulas of Indian music, known as raga, are as timeless as the law of gravity and must be discovered, much like the Vedas themselves. Each raga embodies a particular rasa (mood or flavor) and can thus generate those same feelings within both the listener and the performer when properly invoked. When those feelings are directed towards God as Brahman or Ishvara, the result is higher attachment (also called raga). And if the music is both understood as Nada-Brahman and performed properly

in the spirit of bhakti or bhakti-rasa, then the musician and the listener are said to gain release and the association of Ishvara (Supreme Controller) in both this life and the next. Musicians in India have a saying: “through svara (musical notes), Ishvara (God) is realized.”

Tala (rhythm) is also of great importance in Indian music. Vedic ritual chants were punctuated by metrical divisions. Besides aiding memorization, these divisions–when chanted–were believed to generate distinct units of merit that accrued to the priest or sacrificer, leading to afterlife in heaven. This connection of music to Vedic merit was explained in classical music texts such as the Dattilam. Since Vedic chanting was metrical, religious music also required a distinct rhythm or division of musical time sequence in order to yield the same benefits. In Gandharva music, similar metrical units were marked by the rhythmic playing of drums and metal hand cymbals (kartal or jhanjh).

Emphasis on devotion

The ancient theory held that performing or hearing music hastened one’s liberation solely through the marking of ritual (musical) time. But in the emerging Bhakti traditions, it was recognized that moksha depends also on one’s emotion or feelings–the depth of one’s personal relationship with the Deity, including the proper rasa and feelings of bhava.

Bhakti literature saw a rapidly expanding assortment of song-texts in regional vernacular languages. Many of these were stimulated by Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, a Sanskrit work of 12th-century Bengal. This text contained linguistic innovations in Sanskrit meter which influenced the development of vernacular musical composition in Prakrit, including special dialects like Braj Bhasha and Brajbuli. The 14th century saw a magnificent outpouring of devotional poetry addressing almost every Deity of the Hindu pantheon, with nearly every region of India producing its own composer of songs to a favored Deity.

In the North, Sur Das wrote about Krishna as Sri Nathji in Braj Bhasha; Tulasi Das addressed Lord Rama in Avadhi; Tukaram and Namdev wrote devotional songs in Marathi to Krishna as Vitthala; Mira Bai addressed Krishna as Giridhar Gopal in both Raja-sthani and Hindi; Vidyapati praised Radha-Krishna and Siva in Maithili and Brajbuli; Chandidas composed songs to Radha and Krishna in Bengali; Govinda Das lauded Radha-Krishna and Chaitanya in Brajbuli; Ramprasad praised Goddess Kali in Bengali; and Shankaradeva venerated Krishna in Assamese. In the South, Purandaradasa expressed his worship of Vishnu in Kannada, and several composed devotional songs in the Telegu language–Syama Shastri to Goddess Kamakshi, Annamacharya to Lord Venkateshvara, and Tyagaraja to Lord Rama. These and many other composers are believed to have attained eternal liberation through their songs.

Classical music, East and West

Just as Christian church music has strongly influenced the development of Western classical music, these various traditions of Indian religious music in India, which developed in specific sacred places and within religious lineages, have been a rich source of material for Indian classical music. “Classical ” music in India–as in the West–refers to music performed primarily as a form of art, for entertainment, by professional, skilled artists. Therefore, the development of this music is influenced by the preferences of patrons, individual improvisation and even foreign influences. This type of music tends to place great emphasis on virtuosity, creativity and “art for art’s sake.” The distinct northern and southern classical music traditions gradually developed from this background some time after the thirteenth century.

Carnatic music

Southern Carnatic music is grounded upon the devotional music performed by Vaishnava and Saiva saints in the temples and shrines of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. A major influence was provided by Purandaradasa (1480-1564), a Vaishnava musician said to have written nearly half a million songs known as Kirtanas. Hailed as the father of Carnatic music, Purandaradasa was the main inspiration of Tyagaraja (1759-1847), whose devotional Kritis (compositions) in Telegu to Lord Rama dominate the current repertoire of South Indian music. Tyagaraja is recognized as part of a trinity of great musician-poets from Tiruvarur which included Syama Shastri and Muttuswami Dikshitar, composers of songs to the Goddesses Kamakshi and Minakshi.

Hindustani music

The Hindustani music of the northern regions stems from the temple music, especially Dhrupad, that was performed by Vaishnava musicians in Mathura, Vrindaban and Gwalior as well as Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Bengal and Uttar Pradesh. The Persian and Islamic Sufi influences in the North also affected the development of Hindustani music.

The musical style of Dhrupad provided an ideal vehicle for the vernacular Bhakti lyrics. Several new related genres of music emerged, including Haveli-Sangit, Samaj-Gayan and Padavali-Kirtan. Dhrupad, linked to the Prabandha songs of earlier Sanskrit treatises, refers to the formal, slow, four-section vocal rendition of a poem using the pure form of a raga, along with the rhythms of mainly Cautal (12 beats) and Dhamar (14 beats). Most of these new devotional poems contained at least four lines, so there was a natural division into the four parts of Dhrupad–sthayi, antara, sancari and abhog. Dhrupad spread as a classical form wherever it was patronized by the ruling elite, in temples as well as the Hindu and Mughal courts.

A famous name in Hindustani music is Sur Das (16th century), a blind musician-poet associated with the Vallabha Sampradaya (Pushtimarga tradition) who spent his entire life singing to Krishna. In his Braj Bhasha work Sur Sagar, he praised singing as the most viable means of spiritual liberation. Sur Das was a member of the Ashta-chap, a group of poets considered foundational by some historians in developing and refining the Dhrupad style later known as Haveli Sangita–a form of temple music which is believed to be one of the forerunners of Hindustani music. In fact, many songs in the Hindustani vocal classical repertoire are drawn directly, or else paraphrased, from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Braj Bhasha lyrics that describe the pastimes of Krishna, including especially the festival associated with Holi in the spring season and the Rasa Dance in autumn. Originally established in the Braj area, Haveli Sangit is now more widely practiced in the Vallabha headquarters in Nathadvara in Rajasthan. Many musicians known as kirtankars, attached to Vallabha or Pushtimarga temples and centers in Rajasthan, Gujarat and Mumbai, continue to perform Haveli Sangit.

Swami Haridas (ca 1500-1595), the founder of a Vaishnava lineage in Vrindaban, was another expert singer and musician of the Dhrupad style. Considered the father of Hindustani music, he was the teacher of the legendary Tansen, who sang at the court of Akbar in the 16th century and whose disciples were almost solely responsible for the transmission of Hindustani classical music through the Mughal period and thereafter. The various gharanas of Hindustani music today trace their lineages back to Tansen, or else to Swami Haridas or Baiju Bawra, both Hindu devotional singers. Beside the Seniya (direct from the family of Tansen), some of the famous gharanas are Gwalior, Agra, Patiala, Rampur, Kirana, Jaipur and Indore.

Although Akbar and his immediate successors, Jehangir and Shahjahan, were generally supportive of Indian music in their courts, music was banned after the rise of the puritanical Aurangzeb. Many musicians fled the Delhi area to take up work in outlying regions like Tirth Raj Prayag (Luck-now), Varanasi, Vishnupur in Bengal and ultimately Kolkata, where British colonials had become increasingly interested in Indian music by the mid 1750s. We owe a debt of gratitude to the Muslim families of many musicians who carried forth and preserved the art of classical music through those troubled times. It was not until the early twentieth century that, due to the efforts of pioneer scholar-musicians like V.N. Bhatkhande and V.D. Paluskar, Indian music was “relearned ” by many Hindu musicians and began to receive due recognition on the concert stage and from general educational institutions. Modern music academies like the ITC Sangeet Research Academy in Kolkata (founded in 1978) are doing yeoman service in the preservation and dissemination of Hindustani music. Likewise, the Music Academy in Chennai has carried forth the Carnatic tradition in the south.

Pan-Indian musical tradition

The musical texts and traditions cited above provided a common root for a pan-Indian musical tradition, setting standards of scale and rhythm systematization. This allowed Indian music to develop along very similar lines regardless of context or sectarian affiliation. Whether they believed in Nirguna (Absolute without qualities), Saguna (Absolute with qualities), Vaishnava, Saiva, Sakta or other Deities, all musicians drew from the same evolving corpus of musical genres, raga patterns, tala structures and assortment of instruments.

Music for religious purposes

Indian music performed for religious purposes focuses closely on the text and its clear pronunciation, at the same time maintaining established patterns of performance over many generations. Although melody and rhythm are important, musical virtuosity for its own sake is normally discouraged, as a distraction from the devotional purpose of the music, in Hindu temples and religious gatherings, unlike the developing classical traditions which place great emphasis on improvisation and technical mastery.

Religious musical sessions are usually observed as group enterprises, with participants seated on the floor. Generally a particular area in the home or temple, facing or adjacent to a Deity or picture, is designated for music. The lead singer reads from a hymnal–many of which have been published by various religious groups–with the group repeating afterwards in unison. The leader may also sing solo or with occasional refrains by the group.

Lead singers often accompany themselves on the harmonium. This is a floor version of the upright, portable reed organ used by 19th century Christian missionaries; but its metal reed is South Asian in origin, linked to the pungi or snake-charmer’s instrument, and is the basis for the Western harmonica and accordion.

Other instruments used in bhajan may include pairs of hand cymbals called kartal or jhanjh, drums such as the tabla, pakhavaj, dholak or khole and occasionally bells, clappers or tambourines. Bowed chordophones, such as the sarangi or esraj, may accompany the singing, but the harmonium has tended to replace these. A background drone may be provided by a tambura, harmonium or shruti box, a small pumped instrument used in Carnatic music.

Modern bhajan

Nearly every Hindu religious gathering includes chanting or music; but in both India and the Hindu Diaspora, many earlier forms of devotional music are being supplanted by a looser style of bhajan. In the Bhakti tradition of class egalitarianism, bhajan sessions continue to stress openness to people of all social strata and are a frequent component of congregational rites in which there is a sharing of bhakti experiences.

Bhajan gatherings–whether male, female, or mixed–tend to be flexible regarding attendance and may take place anytime. Some bhajan sessions last continuously (24 hours) for several days, particularly in Bengal, where intensive akhanda ( “unbroken “) sessions of Nam-Kirtan are regularly held. The atmosphere of the bhajan session fosters intimate and informal social relationships where all participants sit, sing, and eat together regardless of caste, gender or religious viewpoint.

Beginning with the chanting of Om, a bhajan session proceeds with invocations in Sanskrit in honor of a guru, master, or Deity, followed by sequences of bhajan songs that reflect the group’s distinct or eclectic religious outlook, sometimes punctuated by short sermons or meditative recitations of Sanskrit verses from scriptures. Toward the closing, an arati (flame-waving) ceremony is conducted as part of the puja (worship service), which includes offerings of food, flowers, incense, lamps, and the blowing of conches. The puja concludes with the passing of the flame and distribution of food, flowers and holy water to the devotees.

Bhajan can also be part of one’s private worship, in conjunction with chanting on rosary beads, singing to oneself during personal puja activities and the chanting of scripture. The rosary chanting of mantras, called japa, is not done in a singing style with a melody but normally rendered in declamatory fashion in one or two monotones. Indeed, from Vedic chanting to classical singing to bhajan, the power of the sustained musical tone or note within the Indian consciousness cannot be overemphasized.

As musical compositions, bhajan songs in the current context range from complex structures to simple refrains or litanies containing divine names. Most have their own distinctive tune and rhythm that is easily followed by the public, though some are based on classical ragas and talas and require musical skill. The most common talas are up-tempo, such as keherva, eight beats roughly corresponding to a Western cut-time in 4/4. This rhythm, along with the use of the harmonium and the dholak drum, became prominent in the Muslim Sufi singing tradition known as Qawwali. The sixteen-beat tintal tala serves as a variable straight 4/4 time sequence with an accent on the first beat. Another common rhythm is dadra, a six-beat tala corresponding to Western 3/4 or 6/8.

One of the most refined forms of devotional music in India is the Padavali-Kirtan of Bengal. This form extends back almost 500 years to the time of Chaitanya Maha-prabhu, who is viewed as an incarnation of Krishna. It combines recitation of religious narratives with songs composed by Bhakti saints in Bengali or Braj-buli language. The songs include short improvisatory phrases called akhar added into the song-texts by the singers themselves in order to interpret or reiterate the meaning in colloquial language for the benefit of the audience. The performers usually include one or more vocalists, a khole player (drummer), a hand cymbal player and sometimes a violinist or flautist.

The public or group singing of the names of God, as in Sita-Ram, Hare Krishna, Hare Rama, Radhe Shyam, Om Namah Sivaya, Jai Mata Di, etc., is very popular everywhere in India and is called Nam-Kirtan, Nam-Sankirtan or Nam-Bhajan. In the South, the Nama-Siddhanta tradition of Bodhendra, Sri Venkatesha and Sadguruswami developed a distinctive Advaitic tradition of Nam-Bhajan. Many South Indian bhajans are adaptations of these original songs. Sung to simple melodies accompanied by drums and cymbals, Nam-Kirtan or Nam-Bhajan expresses fervent devotion and serves as a means of spiritual release.

Religious and devotional music permeate the modern movements of Hindu leaders such as Swami Sivananda, Satya Sai Baba, Anandamayi Ma, Sri Aurobindo, Swami Rama, Srila A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and many others. Bhajans are also widely performed, even among non-Indians and non-Hindus. A new style of improvised solo bhajan has entered the classical concert stage. The “Pop Bhajan ” has achieved great success, along with devotional songs sung by playback singers in Indian films. Film aratis such as “Om Jaya Jagadish Hare ” (heard in the Hindi film Purab aur Paschim) are now widely used in both home and temple worship ceremonies all over the world.

Conclusion

Indian music remains an extraordinarily significant component of all aspects of secular life and religious practice wherever Indian culture is present. It aids in maintaining cultural ties, religious faith and moral discipline. Performed by skilled musicians or lay enthusiasts, Indian music continues to serve as both a vehicle for entertainment and a source of spiritual renewal and ecstasy. Alongside the modern popular, film and bhajan forms, the traditional religious and devotional music endures in temples, shrines and domestic chapels throughout India and the Hindu diaspora. And India’s classical music is steadily gaining world attention on a serious scale.

HINDU MUSIC, NOW AND INTO THE FUTURE

GUY BECK IS ONE OF THE FIRST AMERICANS TO BECOME PROFICIENT IN THE TRADITION OF NORTH INDIAN HINDUSTANI VOCAL MUSIC AND THE FIRST TO APPEAR IN AN ALL-INDIA MUSIC CONFERENCE (TANSEN SANGIT SAMMELAN, 1977, 1979, 1992). HE HAS PERFORMED AT THE INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF VEDANTA (1994), THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF RELIGION (1998) AND AT OXFORD UNIVERSITY (2001). HE HAS PERFORMED ON RADIO NEPAL (1980) AND ON INDIAN TV DOORDARSHAN- (1993).

DR. BECK, WHAT IS THE CURRENT STATE OF TRADITIONAL HINDU MUSIC?

INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC HAS SLOWLY EVOLVED INTO A POLISHED ART FORM THAT IS BEING DISSEMINATED THROUGHOUT INDIA AND ABROAD BY A RAPIDLY DEVELOPING COTERIE OF CELEBRITY PERFORMERS ON RADIO, TELEVISION, CONCERT STAGES AND ON RECORDED MEDIA.

PRIOR TO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, THE PRIMARY MEANS OF LEARNING NORTH INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC WAS TO BE BORN INTO A GHARANA OF MUSICIANS THAT WERE PATRONIZED BY THE ROYAL COURTS, MANY OF WHICH WERE MUSLIM. UNDER BRITISH RULE, THE GHARANAS DETERIORATED RAPIDLY. BEGINNING AROUND 1910, A NUMBER OF BOLD AND AGGRESSIVE PIONEERS AMONG THE HINDU INTELLIGENTSIA, WHO HAD TAKEN TRAINING FROM MANY OF THE MUSLIM USTADS (MAESTROS), SET OUT TO ESTABLISH OPEN-ENROLLMENT MUSIC SCHOOLS THAT WOULD ALLOW STUDENTS FROM ALL BACKGROUNDS TO LEARN CLASSICAL RAGAS AND TALAS IN VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. THE NAMES OF PANDIT V.D. PALUSKAR AND PANDIT V.N. BHATKHANDE STAND OUT IN THIS REGARD, AS THEY WORKED HARD TO BRING HINDUSTANI CLASSICAL MUSIC TO THE GENERAL POPULATION. ALL-INDIA MUSIC CONFERENCES WERE SOON HELD THAT SHOWCASED GREAT ARTISTS BEFORE THE GENERAL PUBLIC AND PAVED THE WAY FOR THE CONCERT HALL RECITALS OF TODAY. DURING THE PERIOD FROM 1930 TO 1950, AFTER THE ESTABLISHMENT OF DEMOCRATIZED LEARNING FACILITIES, CLASSICAL MUSIC ALSO BECAME A SOURCE OF PATRIOTIC PRIDE AMONG THE INDIAN POPULATION, AS IT SUPPORTED THE FREEDOM MOVEMENT TOWARD INDIAN INDEPENDENCE. CLASSICAL RENDITIONS OF ANTHEMS LIKE VANDE MATARAM ( “GLORY TO MOTHER INDIA “) BECAME WIDELY POPULAR, AND THERE DEVELOPED A CLOSE RAPPORT BETWEEN HINDU AND MUSLIM MUSICIANS AS THEY PERFORMED TOGETHER AND LEARNED FROM ONE ANOTHER.

THE GHARANA SYSTEM IN THE NORTH AND THE GURU-SHISHYA SYSTEM IN THE SOUTH MAINTAINED THE TRADITIONAL FOCUS WHEREBY A STUDENT WOULD LEARN, PERFECT AND PERPETUATE A DISTINCT STYLE OF MUSIC. THIS IS STILL OBSERVED BY CONSERVATIVE ARTISTS; BUT THERE IS A GROWING TENDENCY, ESPECIALLY AMONG YOUNGER MUSICIANS, TO MIX TRADITIONS AND TO GIVE EMPHASIS TO CREATIVITY OF EXPRESSION. IN MANY MUSIC SCHOOLS, HOWEVER, ADHERENCE TO THE PURITY OF ONE’S SPECIFIC TRADITION REMAINS THE NORM AND GUIDELINE FOR THE TRANSMISSION OF MUSICAL EDUCATION, ESPECIALLY IN THE CONTEXT OF ONE-ON-ONE MUSIC LESSONS.

HOW DO YOU SEE THIS MUSIC FIFTY TO A HUNDRED YEARS FROM NOW?

WHEN WESTERNERS FIRST ENCOUNTERED INDIAN MUSIC, THERE WAS MUCH POTENTIAL FOR MISUNDERSTANDING AND MISINTERPRETATION. TO THE WESTERN EAR, HABITUATED TO SOOTHING HARMONIES AND CHORD RESOLUTIONS, THE MODAL SOUNDS OF THE RAGA STRUCTURES WERE UNFAMILIAR; AND THE RHYTHMS SEEMED TOO COMPLEX TO GRASP, AS THEY VENTURED FAR BEYOND THE 4/4, 3/4, OR 6/8 TIMING TO WHICH EUROPEANS HAD BECOME ACCUSTOMED. IN TERMS OF THE VOCALIZATIONS, THERE WERE VERY UNFLATTERING RESPONSES TO THE LONG ALAPS AND VISTAR (DEVELOPMENT) CHARACTERISTIC OF DHRUPAD AND KHAYAL PASSAGES, WHICH SOUND LIKE LONG EXTENSIONS OF VOWELS WITHOUT MEANING. BUT AS EUROPEAN MUSICOLOGISTS BEGAN TO STUDY THE THEORY OF INDIAN MUSIC, THEY WERE ASTONISHED TO FIND GREAT PROFUNDITY AND DEPTH OF RELIGIOUS MEANING. DESPITE THE FACT THAT MANY OF THE MUSICIANS WERE MUSLIM, THOSE EUROPEANS WHO KNEW SOME HINDI COULD DETECT THE PRESENCE OF NAMES AND PASTIMES OF HINDU GODS IN THE LYRICS.

WITH THE FALL OF THE COURTS OF THE HINDU MAHARAJAS AND MUSLIM NAWABS TOWARD THE END OF THE 19TH CENTURY, INDIAN MUSICIANS GRADUALLY MADE THE TRANSITION TO THE CONCERT STAGE, RADIO STATION AND RECORDING STUDIO AS THESE MAESTROS BECAME KNOWN TO THE GENERAL PUBLIC. IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY, THE HARMONIUM WAS INTRODUCED FROM THE WEST AND RAPIDLY BECAME A STAPLE IN TEACHING INDIAN MUSIC TO NEW STUDENTS. IT WAS WELL SUITED TO THAT USE, ALLOWING RAGAS TO BE PLAYED IN ACCOMPANIMENT OF VOICE WITH GREATER EASE THAN ON THE VINA OR SARANGI. ALTHOUGH USED IN MAJOR MUSIC CONFERENCES SINCE THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY, FOR MANY YEARS THE HARMONIUM WAS BANNED BY THE ALL INDIA RADIO AS UNSUITABLE FOR INDIAN MUSIC. THAT BAN WAS FINALLY LIFTED DURING THE 1990S. THERE CONTINUES TO BE OPPOSITION FROM CONSERVATIVE FACTIONS SUCH AS PURISTS OF RABINDRA-SANGIT (THE MUSICAL RENDERING OF THE POEMS OF NOBEL LAUREATE RABINDRANATH TAGORE).

SINCE THE MIDDLE OF THE 20TH CENTURY THERE HAS BEEN A CONSENSUS AMONG TEACHERS AND INSTITUTIONS OF INDIAN MUSIC TO STRICTLY MAINTAIN THE INTEGRITY OF THE MUSIC ACCORDING TO THE GHARANA AND GURU-SHISHYA SYSTEMS, WHICH HAVE PRESERVED THE PURITY OF THE VARIOUS SINGING AND PLAYING STYLES OVER MANY GENERATIONS. INDIANS WERE ALSO, SINCE INDEPENDENCE, DEVELOPING A NEW-FOUND PRIDE IN THEIR HERITAGE AND CULTURE. WITH THE CLASSICAL RENDERING OF VANDE MATARAM, INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC EVEN BECAME A SYMBOL OF THE STRUGGLE FOR SELF-RULE.

NEW TYPES OF INDIAN MUSIC ARE BEING CREATED ALL THE TIME. WESTERN JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSICIANS HAVE SHOWN A GROWING FASCINATION WITH INDIAN CLASSICAL SOUNDS, ALTHOUGH MANY OF THESE MUSICIANS DO NOT TAKE THE TROUBLE TO GET FORMAL TRAINING. THERE HAVE BEEN MANY EXPERIMENTS IN NEW AGE AND JAZZ FUSION THAT HAVE CAUGHT PUBLIC ATTENTION. HOWEVER, NONE OF THIS HAS HAD MUCH IMPACT ON THE COURSE OF INDIAN CLASSICAL TRADITIONS. THERE REMAINS A SOLID GROUP OF PLAYERS AND LISTENERS DEDICATED TO THE SURVIVAL INTO THE FUTURE OF THE RICH TRADITIONS OF THE CLASSICAL MASTERS.

HOW WOULD YOU ASSESS THE EXPERTISE AND EDUCATION OF YOUNG INDIAN MUSICIANS?

TODAY’S YOUNGER MUSICIANS HOLD A GREAT DEAL OF RESPONSIBILITY IN PRESERVING AND TRANSMITTING INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC TO THE NEXT GENERATION. FROM WHAT I HAVE HEARD, THERE ARE MANY OUTSTANDING YOUNGER MUSICIANS VERY SUCCESSFULLY DELIVERING THIS PRODUCT. FOR EXAMPLE, PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR’S DAUGHTER ANOUSHKA IS A FINE SITAR PLAYER WHO HAS RECENTLY PERFORMED AT CARNEGIE HALL AND IS CAPABLE OF ATTRACTING MANY NEW WESTERN LISTENERS. PANDIT AJAY CAKRAVARTI’S DAUGHTER KAUSIKI IS AN OUTSTANDING VOCALIST WHO IS CARRYING ON THE AUTHENTIC TRADITION OF THE PATIALA GHARANA. AJAY CAKRAVARTI IS ALSO TRAINING A GROUP OF YOUNGER VOCALISTS AT HIS NEW SCHOOL, ABHINANDAN, IN KOLKATA. THIS COMPLEMENTS THE GREAT WORK OF THE SANGEET RESEARCH ACADEMY IN KOLKATA THAT HAS BEEN TRAINING YOUNGER VOCALISTS SINCE 1978 UNDER THE ORIGINAL DIRECTION OF PANDIT VIJAY KICHLU, AND NOW UNDER PANDIT AMIT MUKHERJEE. SO, I SEE A VERY BRIGHT FUTURE FOR INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC AND ITS TIMELESS MESSAGE OF PEACE AND SERENITY.

HOW STRONG IS ENTHUSIASM FOR INDIAN MUSIC TODAY?

THERE ARE MORE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONFERENCES TODAY THAN EVER BEFORE. THERE ARE ALSO MANY MORE NEW VENUES FOR CLASSICAL MUSIC THAN WHEN I WAS STUDYING IN THE 1970S. THERE HAS BEEN A CORRESPONDING RISE IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY AND IN THE NUMBER OF RETAILERS OF CLASSICAL MUSIC. PREVIOUSLY, BESIDE HMV GRAMOPHONE, FEW RECORDING COMPANIES WERE WILLING TO RISK EXPANDING THEIR CATALOGS OF CLASSICAL ARTISTS. TODAY THERE ARE MANY MORE LABELS, WITH NEW ONES ON THE RISE. ONE NEW LABEL, BIHAAN MUSIC BASED OUT OF KOLKATA, HAS BEEN RELEASING CDS OF MANY LESSER-KNOWN CLASSICAL ARTISTS, SUCH AS MYSELF, AS WELL AS YOUNGER PERFORMERS SEEKING A CONSUMER MARKET. WHEN IN KOLKATA IN 2004, I WAS TOLD BY THE MANAGERS OF BOTH MUSIC WORLD, INC. AND PLANET M, TWO OF THE BIGGEST NEW CHAINS OF MUSIC AND MEDIA RETAILING IN INDIA, THAT THE SALES OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC HAS RISEN SO SHARPLY THAT THEY HAVE BEEN OVERWHELMED WITH CUSTOMERS. THIS ALSO INCLUDES MANY VARIETIES OF RELIGIOUS AND DEVOTIONAL MUSIC. THE MUSICAL GENRES IN INDIA ARE SO FINELY DIVIDED THAT THERE REALLY ISN’T A GENERIC CATEGORY KNOWN AS “FOLK ” MUSIC AS UNDERSTOOD IN THE WEST. THERE ARE TYPES OF LOK-SANGIT, MUSIC WITH LIMITED REGIONAL OR LINGUISTIC OUTREACH, THAT MAY BE CONSIDERED AS FOLK, BUT MOST OF THIS REMAINS LARGELY UNRECORDED TODAY.

IS THERE ENTHUSIASM FOR INDIAN MUSIC IN THE WESTERN AUDIENCE?

MANY RECALL THAT BEFORE THE POPULARIZATION OF PT. RAVI SHANKAR AND USTAD ALI AKBAR KHAN IN THE WESTERN MUSIC SCENE IN THE 1960S, HARDLY ANYONE IN THE WEST HAD HEARD OF HINDUSTANI CLASSICAL MUSIC. THEN IT BECAME SOMETHING OF A FAD THAT WAS COMBINED WITH THE EMERGING HIPPIE SUBCULTURE. I REMEMBER SPEAKING WITH PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR IN KOLKATA IN 1979, AND HE SINCERELY REGRETTED THAT HIS MUSIC WAS STILL ASSOCIATED WITH THE DRUG CULTURE IN THE US AND HAD BEEN STEREOTYPED AS A KIND OF SOUNDTRACK FOR THE PSYCHEDELIC EXPERIENCE. I HAD ATTENDED SEVERAL OF HIS US CONCERTS IN THE 70S, AND HIS STATEMENTS RANG TRUE. BUT AS I STUDIED THE TRADITION FURTHER IN INDIA, I QUICKLY REALIZED THAT IT HAD NOTHING TO DO WITH ARTIFICIAL INTOXICATION, BUT HAD ITS OWN EUPHORIC DIMENSION COMPLETELY UNRELATED TO REBELLIOUS UNDERGROUND CULTURES. LISTENING TO SITAR MUSIC WAS ACTUALLY KIND OF AN “ELITE ” OCCUPATION.

IN ORDER FOR INDIAN MUSIC TO RECEIVE THE RESPECT AND ACCLAIM THAT IT DESERVES IN THE WEST, THESE STEREOTYPES ASSOCIATED WITH HIPPIE CULTURE MUST BE BROKEN THROUGH PROPER MEDIA ATTENTION. SADLY, AS OF TODAY, I HAVE NOT SEEN OR HEARD ANY CONCERT OR INTERVIEW BROADCAST ON NETWORK (OR CABLE) TV IN RESPECT OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC OR ITS HISTORY. WE ARE LONG OVERDUE IN THIS COUNTRY FOR A PROPER DOCUMENTARY ON PUBLIC TELEVISION, A&E OR THE HISTORY CHANNEL. THERE ARE MANY GREAT MASTERS OF INDIAN MUSIC WHO ARE STILL ALIVE AND PERFORMING. WHY HASN’T PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR APPEARED ON ANY FEATURE TALK SHOWS OR INVESTIGATIVE REPORTS? I NOMINATE HIM FOR THE KENNEDY CENTER AWARD.

HOW HAVE INSTRUMENTS EVOLVED THROUGH THE YEARS?

THE SAME BASIC INSTRUMENTS THAT HAVE BEEN PROMINENT IN THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS ARE STILL THE MOST IMPORTANT IN HINDUSTANI AND CARNATIC MUSIC. HOWEVER, INNOVATIVE MUSICIANS HAVE SUCCESSFULLY BROUGHT IN THE VIOLIN, GUITAR, SAXOPHONE AND EVEN PIANO (TO A LIMITED EXTENT), TO THE CONCERT STAGE AND RECORDING STUDIOS. EVEN HYBRID INSTRUMENTS ARE GAINING A FOOTHOLD. I RECENTLY PERFORMED A CONCERT AT THE SNUG HARBOR JAZZ BISTRO IN NEW ORLEANS WITH ANDREW MCLEAN ON TABLA AND TONY DAGRADI ON SAXOPHONE. WHILE I WASN’T USED TO WORKING WITH SAXOPHONE, THE MUSICIAN WAS CAPABLE OF BLENDING WITH THE MOOD OF THE RAGA, AND THIS INNOVATION CREATED MANY NEW EFFECTS. ANDREW ALSO PLAYED ELECTRIC SITAR BY PLACING AN ELECTRONIC SITAR PICK-UP ON HIS FENDER STRATOCASTER! THE CROWD WAS DELIGHTED.

WILL SYNTHESIZERS HAVE IMPACT?

WHILE THERE HAS BEEN THE SUCCESSFUL ADOPTION OF MUSIC SYNTHESIZERS IN POP MUSIC AND TO SOME EXTENT IN FUSION, I DON’T BELIEVE THAT THEY WILL ALTER INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, WHICH REQUIRES ITS OWN PARTICULAR BLEND OF ACOUSTIC SOUND TO CREATE AND SUSTAIN THE IDEAL LISTENING EXPERIENCE. MUSIC TECHNOLOGY HAS ADVANCED THE ACCESS TO GOOD INDIAN SOUND BEYOND THE NEED TO ACQUIRE TRADITIONAL INSTRUMENTS, HOWEVER. THE TANPURA SOUND CREATED BY ELECTRONIC DEVICES LIKE “RAGINI PRO ” AND THE TABLA SOUNDS OF “TAL TARANG ” ARE EXCELLENT, AND REMOVE THE NEED OF CARRYING AROUND THE LARGER INSTRUMENTS FOR INFORMAL USE. THOUGH NOTHING CAN SUBSTITUTE THE REAL THING ON THE CONCERT STAGE, ELECTRONIC INSTRUMENTS ARE USEFUL FOR PRACTICING AND SMALL GATHERINGS, AND THUS HELP TO SUSTAIN THE INTEREST AND ACCESSIBILITY OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC. THE ALI AKBAR KHAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN SAN FRANCISCO, BESIDES PROVIDING LESSONS AND INSTRUCTION, IS PERFORMING AN IMPORTANT TASK IN STOCKING AND SELLING ALL TYPES OF ACOUSTIC AND ELECTRONIC INSTRUMENTS.

WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER THE MOST RELIGIOUS MUSICAL EXPRESSION?

THERE IS MUCH FOLK MUSIC IN INDIA THAT APPEARS NON-RELIGIOUS, SUCH AS WEDDING SONGS, WORK SONGS, RECITATIONS OF VILLAGE LIFE, LOVE SONGS, ETC. SEEN IN THE CONTEXT OF THE HINDU WORLD VIEW, THESE ALSO CAN BE CONSIDERED “RELIGIOUS.” HOWEVER, AS MOST OF THE CLASSICAL SONG LYRICS ARE DIRECTLY BASED ON THEOLOGICAL THEMES (I.E., KRISHNA’S PASTIMES, PRAISE OF SIVA OR THE GODDESS, ETC.), THEN I WOULD PLACE THESE COMPOSITIONS SQUARELY WITHIN THE RELIGIOUS CATEGORY.

HOW DO YOU SEE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IMPACTING THE MUSIC?

THE RAPID RISE IN TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATIONS HAS MADE MUSIC MUCH MORE AVAILABLE (ON THE WEB, IPODS, ETC.), MAKING IT POSSIBLE FOR MANY INDIVIDUALS, WHO OTHERWISE WOULD HAVE NO EXPOSURE, TO LEARN ABOUT AND LISTEN TO INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC. MANY NEW CD RECORDINGS OF THE OLD MASTERS HAVE BEEN RELEASED, OR RE-RELEASED, PROVIDING AN UNPRECEDENTED OPPORTUNITY FOR COLLECTORS AND CONNOISSEURS, AS WELL AS NEWCOMERS, TO GAIN FREE ACCESS TO MANY TREASURES. THE WORLD COMMUNITY IS THUS MUCH MORE INTERCONNECTED THAN EVER BEFORE; HOWEVER, SOME RELIGIOUS IDEOLOGIES REJECT TECHNOLOGY AND MUSICAL DEVELOPMENT. I THINK THAT MAJOR CHANGES MUST BE MADE IN THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF HUMAN VALUES WORLDWIDE IF INDIAN MUSIC IS TO REACH THOSE SEGMENTS OF THE POPULATION. FURTHERING THE GOAL OF MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING, 2006 SAW THE PUBLICATION OF MY SECOND BOOK, SACRED SOUND: EXPERIENCING MUSIC IN WORLD RELIGIONS (HTTP:/WWW.WLU.CA/PRESS/CATALOG/BECK.SHTM [http:/www.wlu.ca/press/Catalog/beck.shtm]).

LIFE STORY

MY CONTINUING JOURNEY INTO THE WORLD OF INDIAN MUSIC

MY PERSONAL JOURNEY INTO INDIAN MUSIC BEGAN IN CHILDHOOD WITH A FASCINATION FOR YOGA AND THE STORIES OF RUDYARD KIPLING. DURING MY TEENAGE YEARS, AS I STUDIED CLASSICAL PIANO, I NOTICED THAT SEVERAL WESTERN COMPOSERS, SUCH AS LISZT, SAINT-SAENS, RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, ETC., UTILIZED ORIENTAL OR MIDDLE-EASTERN SOUNDING SCALES OR MODES IN THEIR MUSIC, PRODUCING DIFFERENT EMOTIONAL EFFECTS THAT CONJURED UP EXOTIC LANDS AND CULTURES.

WHEN THE MUSIC OF PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR AND USTAD ALI AKBAR KHAN BECAME POPULAR IN THE 1960S, I FELT SIMILAR EFFECTS IN THEIR RENDITIONS OF CERTAIN RAGAS AND IMPROVISATIONS, DRAWING ME INTO THEIR ENCHANTING WORLD OF TONE AND RHYTHM. I HAD A NATURAL URGE TO LEARN TO PLAY THE SITAR, AND I EVEN CONTEMPLATED ORDERING ONE FROM A SHOP IN NEW YORK. HOWEVER, SINCE I WAS ALREADY A PIANIST, AND TO SOME EXTENT A SINGER IN SCHOOL CHOIRS AND ENSEMBLES, I DECIDED TO EXPLORE THE VOCAL TRADITION OF NORTH INDIAN MUSIC, AIDED BY THE HARMONIUM, A REED-DRIVEN PORTABLE ORGAN OFTEN USED TO ACCOMPANY INDIAN DEVOTIONAL AND CLASSICAL SINGING. I HAD FIRST HEARD THIS INSTRUMENT IN THE HARE KRISHNA TEMPLES OF NEW YORK AND LOS ANGELES, AS WELL AS AT THE YOGA ASHRAMS OF THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY AND MAHARISHI MAHESH YOGI. HEARING THE DEVOTIONAL SINGING AND HARMONIUM PLAYING OF HIS DIVINE GRACE A. C. BHAKTI-VEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPADA IN 1972-1974 INTRODUCED ME TO THE POTENCY OF THE VOICE IN RENDERING A VERNACULAR DEVOTIONAL LYRIC. FURTHERMORE, VISITS TO SWAMI NADABRAHMA-NANDA AT THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY IN NEW YORK, IN 1975 AND 1976, FIRST EXPOSED ME TO THE CLASSICAL NORTH INDIAN MUSIC TRADITION OF SINGING WITH HARMONIUM AND TABLA ACCOMPANIMENT.

SWAMI NADABRAHMA-NANDA DESCRIBED MUSIC AS “NADA-BRAHMAN, ” OR CAUSAL SOUND, AND TAUGHT THAT IT WAS MEANT FOR MUCH MORE THAN MERE ENTERTAINMENT. IT WAS SUPPOSED TO BECOME A VEHICLE FOR ATTAINING RELEASE FROM REBIRTH AND FOR REALIZATION OF BRAHMAN. THAT WAS ALL I NEEDED TO KNOW TO EMBARK ON A TRIP TO INDIA IN SEARCH OF A MUSICAL GURU IN 1976. I INITIALLY TRAVELED FAR AND WIDE–TO HARDWAR, RISHIKESH, MATHURA, VARANASI, JAIPIR, ETC.–BUT IT SEEMED MOST PRUDENT TO SETTLE IN A LARGE CITY AND SEEK OUT A REPUTABLE MUSIC ACADEMY. JUST AS IF I WERE AN INDIAN NATIVE, I ENROLLED AS A BEGINNING STUDENT AT THE TANSEN MUSIC COLLEGE IN KOLKATA IN JUNE 1976, FELL IN LOVE WITH INDIAN MUSIC AND REMAINED THERE IN INTENSIVE TRAINING UNTIL OCTOBER, 1980, WHEN I CAME BACK TO AMERICA–MAKING RETURN VISITS IN 1988 AND 1992. MY TEACHER AND GURU, SRI SAILEN BANERJEE, PRINCIPAL OF TANSEN MUSIC COLLEGE, PATIENTLY TRAINED ME IN THE SENIYA TRADITION ( “TANSEN “) OF KHAYAL SINGING IN VARIOUS RAGAS. EARLY IN 1978, HE PERFORMED THE NARABANDAN CEREMONY IN HIS HOUSE, IN FRONT OF AN IMAGE OF THE GODDESS SARASVATI, WHICH OFFICIALLY INITIATED ME AS HIS DISCIPLE IN THE TRADITIONAL MANNER.

THE LEGACY OF TANSEN IS IMPORTANT FOR THE PERFORMING TRADITION OF HINDUSTANI MUSIC. TANSEN WAS THE PRINCIPAL SINGER IN THE COURT OF EMPEROR AKBAR DURING THE 16TH CENTURY. HIS STYLE OF DHRUPAD SINGING PLAYED A PIVOTAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE VOCAL TRADITION OF KHAYAL AS WELL AS INSTRUMENTAL STYLES. MOST HINDUSTANI MUSICIANS TODAY, INCLUDING PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR AND USTAD ALI AKBAR KHAN, TRACE THEIR MUSICAL HERITAGE TO TANSEN. PROF. BANERJEE OF THE TANSEN MUSIC COLLEGE CONTINUED THIS VOCAL TRADITION, AS HE WAS A DISCIPLE OF USTAD DABIR KHAN, A VOCALIST AND VINA PLAYER DESCENDED FROM THE FAMILY OF TANSEN. AS HIS STUDENT AND DISCIPLE, I PRACTICED VOCAL EXERCISES FOUR TO SIX HOURS DAILY AND REPORTED TO HIM TWICE A WEEK FOR LESSONS. AFTER AN INITIAL PERIOD OF ONE AND ONE-HALF YEARS, HE JUDGED AND EVALUATED ME AS READY TO PERFORM IN A RECITAL BEFORE THE PUBLIC. HE ARRANGED FOR MY CONCERT AS PART OF THE ANNUAL TANSEN SANGIT SAMMELAN (TANSEN ALL-INDIA MUSIC CONFERENCE) IN DECEMBER OF 1977 AT THE MAHAJATI SADAN IN KOLKATA. MANY FAMOUS ARTISTS SUCH AS USTAD BISMILLAH KHAN, USTAD SHARAFAT KHAN, PANDIT JASRAJ AND SUNANDA PATNAIK PERFORMED AT THIS CONFERENCE. I WAS NERVOUS, BUT I RENDERED RAG KEDAR IN SLOW VILAMBIT AND IN FAST DRUT STYLE TO A LARGE AUDIENCE–AND WAS GIVEN A STANDING OVATION! THERE WAS WIDE NEWSPAPER AND RADIO PUBLICITY, AS THIS WAS THE FIRST TIME THAT AN AMERICAN HAD PERFORMED KHAYAL VOCAL MUSIC IN AN ALL-INDIA CONFERENCE.

AFTER THE INITIAL SUCCESS AT THE TANSEN MUSIC CONFERENCE, I BEGAN TO SUPPLEMENT MY MUSIC TRAINING BY LEARNING SONGS FROM OTHER MAESTROS IN KOLKATA, ESPECIALLY SRI ASHISH GOSWAMI, WHO ALSO SANG IN THE TANSEN AND OTHER LOCAL CONFERENCES. GOSWAMI HAD BEEN A SERIOUS STUDENT OF A VERY FAMOUS MUSICIAN, THE LATE USTAD BADE GHULAM ALI KHAN, FOR SEVERAL YEARS, AND WAS WILLING TO TEACH ME HIS STYLE AND COMPOSITIONS. WEEKLY JOURNEYS OVER THREE YEARS TO HIS RESIDENCE IN A REMOTE AREA OF NORTHERN KOLKATA FOR THIS TRAINING HELPED ME TO DEVELOP MY VOCAL STYLE. SRI GOSWAMI ALSO COACHED ME FOR THE STATE EXAMS IN MUSIC, WHICH I PASSED IN 1980.

ALSO IN NORTH KOLKATA, FROM 1978-1980, I STUDIED DHRUPAD AT THE CHHANDAM DHRUPAD ACADEMY AND STUDIED THE PADAVALI KIRTAN OF BENGAL FROM PROF. MRIGANKA CHAKAVARTI OF RABINDRA BHARATI UNIVERSITY. AND DURING A VISIT TO NEPAL IN 1980, I WAS INVITED TO SING ON RADIO NEPAL AND AT THE PALACE OF KING VIKRAM.

IN 1978, I HAD SPENT FOUR MONTHS IN NEW DELHI, STUDYING VOCAL MUSIC UNDER THE DAGAR BROTHERS OF DELHI, TWO RENOWNED ARTISTS OF DHRUPAD. I ALSO LEARNED DEVOTIONAL BHAJANS FROM THE SANGEET KALA AKADEMI. DURING THIS TIME I LEARNED OF A NEW MUSIC ACADEMY TO BE INAUGURATED SOON IN SOUTH KOLKATA, IN TOLLYGUNGE, CALLED THE ITC SANGEET RESEARCH ACADEMY. RETURNING TO KOLKATA IN MAY, I QUICKLY APPLIED FOR ADMISSION AND WAS ACCEPTED IN THE FIRST CLASS OF STUDENTS.

THIS ACADEMY, FORMALLY INAUGURATED IN SEPTEMBER OF 1978 AND DIRECTED BY PANDIT VIJAY KICHLU, HAD AN EXCELLENT FACULTY WHICH INCLUDED SUCH FAMOUS MUSICIANS AS PANDIT A. KANAN, USTAD NISSAR HUSSAIN KHAN, USTAD LATAFAT HUSSAIN KHAN, SMT. HIRABAI BARODEKAR AND SMT. GIRIJA DEVI. SCHOLARS LIKE PANDIT AJAY CAKRAVARTI AND PANDIT ARUN BHADURI HAD BEGUN THEIR SUCCESSFUL CAREERS THERE.

I STUDIED FOR A TIME WITH BOTH PANDIT KANAN AND PANDIT KICHLU; AND FOLLOWING THE DEMISE OF SRI BANERJEE, I HAVE HAD THE HONOR OF TAKING LESSONS FROM PANDIT ARUN BHADURI, MY PRESENT GURU. WHENEVER I VISIT INDIA, I CONTINUE TAKING LESSONS FROM PANDIT BHADURI, A SENIOR GURU AT ITC, A CLASS A RECORDING ARTIST ON ALL INDIA RADIO AND A SINGER OF OUTSTANDING ABILITIES.

THE CAREFUL FOUNDATION THAT WAS LAID BY SRI BANERJEE PROVIDED THE SOLID BASIS UPON WHICH I HAVE BEEN ABLE TO GO ON LEARNING NEWER STYLES AND COMPOSITIONS. HIS AXIOM WAS THAT ONCE ONE HAD LEARNED A FEW RAGAS THOROUGHLY, THE SKY WAS THE LIMIT.

YET THE POLITICAL CLIMATE OF THAT TIME IN INDIA HAD ITS OWN LIMITS. IN THE SEVENTIES, THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA, UNDER PRIME MINISTER INDIRA GANDHI, WAS AWARDING ONE-YEAR VISAS TO AMERICAN STUDENTS WHO WISHED TO STUDY INDIAN CULTURE. I AVAILED MYSELF OF THIS OPPORTUNITY, BUT HAD TO RENEW THE VISA EACH YEAR FOR THE DURATION. MY STAY WAS FINALLY EXHAUSTED WHEN THERE WERE RUMORS THAT I WAS A CIA AGENT IN DISGUISE! DESPITE LETTERS FROM MY MUSIC TEACHER AND OTHER SUPPORTERS, I WAS UNABLE TO CONVINCE THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA HOME MINISTRY OF MY INNOCENT DESIGNS AND WAS ADVISED TO RETURN TO THE USA. I AM VERY THANKFUL THAT BEFORE MY FORCED RETURN, I HAD REACHED A LEVEL OF COMPETENCY TO HAVE PERFORMED IN SEVERAL ALL-INDIA MUSIC CONFERENCES AND ON RADIO NEPAL AND TO HAVE SUCCESSFULLY PASSED THE THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL EXAMS FOR THE FIVE-YEAR SANGIT BIVAKAR DEGREE OF INDIAN MUSIC AWARDED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL.

ON MY RETURN TO AMERICA, I ENROLLED IN GRADUATE STUDY IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA AND STUDIED MUSICOLOGY AND RELIGION AT SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY, RECEIVING A PH.D. IN 1989. DURING THIS PERIOD, I BEGAN GIVING LECTURE DEMONSTRATIONS ON INDIAN MUSIC TO FELLOW STUDENTS AND FACULTY. I STARTED MY TEACHING CAREER AT LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY IN 1990 AND HAVE SINCE TAUGHT AT LOYOLA UNIVERSITY, THE COLLEGE OF CHARLESTON AND TULANE UNIVERSITY, WHERE I AM CURRENTLY AFFILIATED (ALTHOUGH THIS YEAR I AM TEACHING AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA-WILMINGTON).

IN EACH PLACE, I PERFORMED A SERIES OF CONCERTS AND LECTURES, WHICH LED TO THE RECORDING OF TWO CD’S: SACRED RAGA, RECORDED BY PROF. SANFORD HINDERLIE OF THE COLLEGE OF MUSIC AT LOYOLA UNIVERSITY UNDER THE STR DIGITAL RECORD LABEL IN 1999 AND SANJHER PRADIP, RECORDED AT PLUS GOOD STUDIOS IN BATON ROUGE, LA, BUT RELEASED IN KOLKATA IN 2004 BY BIHAAN RECORDS. I REMAIN DEDICATED TO SPREADING THE ART OF INDIAN MUSIC. (SEE HTTP:/WWW.STRDIGITAL.COM/BECK.HTM [http:/www.strdigital.com/beck.htm] AND HTTP:/WWW.BIHAANMUSIC.COM/GUY-BECK.HTM [http:/www.bihaanmusic.com/guy-beck.htm])

FOR CENTURIES, THE INTELLECTUAL, COGNITIVE AND SPIRITUAL DIMENSIONS OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE HAVE POSITIVELY INFLUENCED THE SLOW BUT GRADUAL RISE OF WORLD CIVILIZATION. I BELIEVE THAT INDIA’S VAST CULTURAL STOREHOUSE, ESPECIALLY ITS CLASSICAL AND DEVOTIONAL MUSIC, WILL COME TO PLAY AN INCREASINGLY IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE WORLD’S MUCH-NEEDED EVOLUTION TOWARD PEACE AND HARMONY. FROM ITS SACRED ORIGINS IN VEDIC SACRIFICES AND HINDU TEMPLES, INDIAN MUSIC IS ALREADY CONSIDERED ONE OF THE GREAT ARTISTIC CONTRIBUTIONS TO WORLD CULTURE.

SINCE THE ARRIVAL IN THE WEST OF PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR AND USTAD ALI AKBAR KHAN IN THE 1950S, SEVERAL AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN PERFORMERS HAVE TAKEN UP INSTRUMENTS LIKE THE SITAR AND SAROD AND HAVE BECOME WELL REGARDED. YET, THE SCARCITY OF AMERICAN VOCALISTS OF INDIAN MUSIC HAS PRECLUDED THE PROCESS OF DEEP CULTURAL ASSIMILATION, SINCE THE UNDERLYING BASIS OF INDIAN MUSIC IS THE VOCAL OR SINGING TRADITION.

AS ONE OF VERY FEW AMERICAN-BORN STUDENTS OF HINDUSTANI OR NORTHERN INDIAN VOCAL MUSIC, I HAVE BEEN WORKING TO EXPAND AND FURTHER THE AIM OF DEEPER CROSS-CULTURAL FERTILIZATION THROUGH LECTURE/DEMONSTRATIONS OF INDIAN MUSIC AT AMERICAN COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES, POINTING OUT THAT INDIAN VOCAL MUSIC CAN BE EFFECTIVELY LEARNED AND APPRECIATED BY NON-INDIANS AND WESTERNERS. BY TRAVERSING CULTURAL BOUNDARIES AND HELPING TO OVERCOME THE INITIAL OBSTACLES OF LANGUAGE AND INTONATION DIFFERENCES, SUCH PRESENTATIONS MAY HELP TO FOSTER GLOBAL HARMONY AND WORLD PEACE THROUGH PROMOTING A MUCH WIDER AND DEEPER APPRECIATION OF VEDIC AND HINDU IDEALS AND CULTURAL TRADITIONS.

E-MAIL DR. BECK AT BECKG@TULANE.EDU.

EAST MEETS WEST

RAVI SHANKAR, BORN APRIL 7, 1920, IN VARANASI, IS THE MOST FAMOUS SITARIST IN RECENT HISTORY, RENOWNED FOR COMPOSITIONS OF VARYING MUSICAL STYLES AND TECHNIQUES. HE IS BEST KNOWN FOR HIS PIONEERING WORK IN BRINGING THE INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC TRADITION TO THE WEST. THIS WAS AIDED BY ASSOCIATION WITH THE BEATLES (NOTABLY GEORGE HARRISON) AS WELL AS HIS OWN PERSONAL CHARISMA. WITH A CAREER SPANNING SIX DECADES, HE HOLDS THE GUINNESS RECORD FOR THE LONGEST INTERNATIONAL CAREER.

RAVI SHANKAR RENOUNCED A DANCE CAREER TO LEARN SITAR AND BEGAN PERFORMING IN 1938. IN THE 1950S, HE BECAME MUSIC DIRECTOR OF ALL INDIA RADIO. HE HAS WRITTEN TWO CONCERTOS FOR SITAR AND ORCHESTRA; VIOLIN-SITAR COMPOSITIONS FOR YEHUDI MENUHIN AND HIMSELF; AND MUSIC FOR FLUTE VIRTUOSO JEAN PIERRE RAMPAL, FOR HOZAN YAMAMOTO, MASTER OF THE SHAKUHACHI (JAPANESE FLUTE) AND FOR KOTO VIRTUOSO MUSUMI MIYASHITA. HE HAS COMPOSED EXTENSIVELY FOR FILMS AND BALLETS IN INDIA, CANADA, EUROPE AND THE UNITED STATES, INCLUDING CHAPPAQUA, CHARLY, GANDHI AND THE APU TRILOGY. CLASSICAL COMPOSER PHILIP GLASS ACKNOWLEDGES SHANKAR AS A MAJOR INFLUENCE, AND THE TWO COLLABORATED TO PRODUCE “PASSAGES, ” A RECORDING OF COMPOSITIONS IN WHICH EACH REWORKS THEMES COMPOSED BY THE OTHER.

SHANKAR MARRIED ANNAPURNA DEVI, DAUGHTER OF HIS GURU, BABA ALLAUDDIN KHAN, AND SISTER OF ALI AKBAR KHAN, IN ALMORA. THE MARRIAGE PRODUCED ONE SON, SHUBHENDRA SHANKAR, BUT ENDED IN DIVORCE. HE BECAME INVOLVED WITH AMERICAN CONCERT PROMOTER SUE JONES; THEY DID NOT MARRY, BUT THEIR UNION PRODUCED ONE DAUGHTER, NORAH JONES. HE LATER MARRIED AN ADMIRER, SUKANYA KOTIYAN (BORN RAJAN), WITH WHOM HE HAD A SECOND DAUGHTER, ANOUSHKA.

ANOUSHKA AND NORAH ARE ALSO MUSICIANS. ANOUSHKA IS A SITARIST WHO PERFORMS FREQUENTLY WITH SHANKAR, IN ADDITION TO HAVING HER OWN RECORDING CAREER. JONES HAS ACHIEVED CONSIDERABLE PROFESSIONAL SUCCESS, INCLUDING SEVERAL GRAMMY AWARDS. SHANKAR IS ALSO THE UNCLE OF LATE SITARIST ANANDA SHANKAR.

JOHN MCLAUGHLIN, ALSO KNOWN AS MAHAVISHNU JOHN MCLAUGHLIN, IS A HIGHLY ACCOMPLISHED GUITARIST FROM DONCASTER, YORKSHIRE, ENGLAND, WHO CAME TO PROMINENCE WITH THE MILES DAVIS GROUP DURING THE LATE 1960S. HE HELPED FORM THE THE MAHAVISHNU ORCHESTRA IN THE 1970S. THE BAND WAS RESPECTED FOR THEIR TECHNICAL VIRTUOSITY AND COMPLEX FUSION OF JAZZ AND ROCK WITH A STRONG INDIAN INFLUENCE. MCLAUGHLIN WAS INFLUENCED IN HIS CONCEPTION OF THIS BAND BY HIS STUDIES WITH HIS GURU, SRI CHINMOY, WHO ENCOURAGED HIM TO TAKE THE NAME “MAHAVISHNU.” MCLAUGHLIN LATER WORKED WITH SHAKTI, WHICH COMBINED INDIAN MUSIC WITH JAZZ. IN ADDITION TO AMALGAMATING WESTERN AND INDIAN MUSIC, SHAKTI ALSO BLENDED THE HINDUSTANI AND CARNATIC MUSIC TRADITIONS, SINCE DRUMMER ZAKIR HUSSAIN (SEE LEFT) IS FROM THE NORTH AND THE OTHER INDIAN DRUMMERS USED WERE FROM THE SOUTH. IN RECENT TIMES SHAKTI REINCARNATED AS REMEMBER SHAKTI, FEATURING EMINENT INDIAN MUSICIANS SUCH AS U. SRINIVAS, V. SELVAGANESH, SHIVKUMAR SHARMA AND HARIPRASAD CHAURASIA.

USTAD ALLA RAKHA AND ZAKIR HUSSAIN

USTAD ALLA RAKHA WAS BORN IN 1919 IN THE VILLAGE OF PHAGWAL, NEAR JAMMU, INDIA. HE BEGAN STUDYING TABLA AT THE AGE OF 12. THE COMBINATION OF GOOD TRAINING AND HOURS OF DISCIPLINED PRACTICE CULMINATED IN SKILLS THAT WOULD MAKE HIM ONE OF THE GREATEST TABLA PLAYERS OF ALL TIME. HE BEGAN HIS MUSICAL CAREER AS AN ALL INDIA RADIO PERFORMER IN MUMBAI, PLAYING THE STATION’S FIRST TABLA SOLO. FROM 1943 THROUGH 1948, HE COMPOSED MUSIC AND PERFORMED; BUT IT WAS DURING THE 1960’S, WITH THE LEGENDARY RAVI SHANKAR, THAT HE ACHIEVED HIS GREATEST FAME IN THE WEST. HE WAS NOT ONLY A MASTERFUL ACCOMPANIST WITH FLAWLESS TIMING AND SENSITIVITY, HE WAS ALSO A UNIQUELY CREATIVE SOLOIST AND AN ELECTRIC SHOWMAN. ALLA RAKHA PASSED AWAY ON FEBRUARY 3, 2000 AT THE AGE OF 80.

FOLLOWING FAMILY TRADITION, ALLA RAKHA’S SON, USTAD ZAKIR HUSSAIN, HAS BECOME A MOST RENOWNED TABLA VIRTUOSO. ZAKIR HAS WON MANY AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS FOR HIS MUSICAL CONTRIBUTIONS. HIS PERFORMANCES HAVE GAINED WORLDWIDE FAME.

TRILOK GURTU WAS BORN INTO A HIGHLY MUSICAL FAMILY IN MUMBAI. HIS GRANDFATHER WAS A NOTED SITAR PLAYER AND HIS MOTHER, SHOBHA GURTU, IS A FAMOUS CLASSICAL SINGER. TRAINED CLASSICALLY ON TABLA FROM THE AGE OF FOUR AND, TODAY, EQUALLY PROFICIENT IN BOTH EASTERN AND WESTERN PERCUSSION TECHNIQUES, TRILOK IS RECOGNIZED AS THE INDIAN TABLA MAESTRO WHO HAS MOST SUCCESSFULLY BRIDGED THE GAP BETWEEN EASTERN AND WESTERN PERCUSSION TO MERGE THE BEST OF BOTH.

A BOND BORN OF MUSIC

TY BURHOE, A DISCIPLE OF THE GREAT TABLA MAESTRO USTAD ZAKIR HUSSAIN (SEE PAGE 33) SINCE 1990, WORKS WITH A BROAD RANGE OF ARTISTS INCLUDING ART LANDE, KRISHNA DAS, BILL DOUGLAS, KAI ECKHARDT, CURANDERO, USTAD SULTAN KHAN, BELA FLECK, KITARO AND MANY MORE. TY ALSO TEACHES DRUMMING AT MUSIC AND YOGA RETREATS AROUND THE WORLD, COMPOSES SOUND TRACKS AND PERFORMS FOR FILM AND VIDEO.

WHAT ATTRACTED YOU TO THE TABLA AND HOW DID YOU GET TO KNOW ZAKIR HUSSAIN? I FIRST HEARD ABOUT TABLA WHEN I WAS 27 YEARS OLD AND JUST GRADUATING FROM COLLEGE WITH A PSYCHOLOGY DEGREE. I WANTED TO LEARN SOME KIND OF DRUMMING AND AND HAD TRIED SEVERAL THINGS, INCLUDING PLAYING IN A BALINESE GAMELAN; BUT IT WASN’T UNTIL I HEARD USTAD ZAKIR HUSSAIN THAT I FELL IN LOVE WITH THE TABLA. I COULDN’T BELIEVE HOW DEEP THE FUSION OF MELODIC AND RHYTHMIC EXPRESSION COULD BE WITHIN A SINGLE INSTRUMENT, ESPECIALLY A DRUM. INSPIRED BY USTAD ZAKIR HUSSAIN’S VIRTUOSITY, LEARNING THE TABLA BECAME AN OBSESSION FOR ME. ALTHOUGH MOST INDIANS WOULD NEVER CONSIDER STARTING CLASSICAL MUSICAL TRAINING AT MY AGE, I HAD A GUT FEELING THAT THIS SINGLE PURSUIT WOULD REDIRECT MY ENTIRE LIFE. IT DID. I BECAME FOCUSED ON PRACTICING AND LISTENING TO EVERYTHING I COULD GET MY HANDS ON. I NEVER THOUGHT I WOULD EVER HAVE THE BLESSING OF STUDYING WITH USTAD ZAKIR HUSSAIN, BUT I DID. MY TRAINING WITH HIM BEGAN IN 1990. I WOULD DRIVE 1,400 MILES FROM BOULDER, COLORADO, TO HIS HOME IN MARIN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, FOR A SINGLE LESSON–THEN TURN AROUND AND DRIVE HOME. I WAS LIVING VERY SIMPLY IN A CABIN IN THE MOUNTAINS. BECAUSE I WAS A SINGLE FATHER, I COULD ONLY MAKE BRIEF TRIPS. MY DEVOTION TO TABLA AND ZAKIR WAS DIFFICULT TO EXPLAIN, EVEN TO MY FRIENDS AND FAMILY. I WAS PRETTY MUCH READY TO DO ANYTHING TO MAKE SURE I WAS PRACTICING EVERY DAY. I NEVER MISSED MY LESSON-PILGRIMAGE. I FELT TRULY BLESSED–AS IF A GREATER FORCE THAN MY OWN WAS AT WORK. IN THIS WAY MUSIC BECAME THE GUIDING FORCE IN MY LIFE, AND HAS REMAINED SO TO THIS DAY.

WHAT ARE THE DIFFERENCES FOR YOU BETWEEN ACCOMPANYING KIRTAN (DEVOTIONAL SINGING) AND OTHER MORE FORMAL FORMS OF MUSIC? IN MOST EVERY MUSICAL ENVIRONMENT, AN ARTIST GENERALLY WORKS TO REFINE AND EXPAND HIS ABILITY TO EXPRESS HIMSELF ON HIS CHOSEN INSTRUMENT. A SOLOIST WHO CAN EXPRESS THE INSPIRED COMPLEXITY AND MULTIPLICITY OF HUMAN FEELING IS CONSIDERED A MAESTRO. IN KIRTAN, HOWEVER, COMPLEXITY BECOMES A DISTRACTION. KIRTAN IS A CALL-AND-RESPONSE BETWEEN THE DIVINE AND OUR SPIRIT. IT CAN BE A VERY INTIMATE AND SPIRITUAL PRACTICE. I LOVE THE ENVIRONMENT OF THE KIRTAN BECAUSE THERE IS NO REAL SEPARATION BETWEEN BEING A PERFORMER AND LISTENER. ALTHOUGH KIRTAN IS GROUP SINGING, EACH PARTICIPANT IS DIRECTLY INVOLVED IN HIS OR HER OWN PERSONAL SPIRITUAL PRACTICE. I FEEL BLESSED TO BE A PART OF THIS PROCESS, AND THE BEST WAY I CAN SERVE IS TO UNDERSTAND HOW MY ROLL AS A TIMEKEEPER IS LIKE A GLUE. THE DRUM PROVIDES THE PULSE WHICH KEEPS EVERYONE IN SYNC. MY MAIN DUTY IS TO LAY DOWN A SOLID AND GOOD-FEELING HEARTBEAT. I AM ALSO A GREAT LOVER OF TRADITIONAL AND WORLD MUSIC. I FEEL THAT BOTH OF THESE WORLDS ARE VERY IMPORTANT.

CAN YOU SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THE RELATIONSHIP OF MUSIC, IMPROVISATION AND SPIRITUAL LIFE? I WOULD SAY THAT “SOUND ” IS CERTAINLY A KEY WAY IN WHICH I RELATE DIRECTLY TO THE DIVINE. FOR MANY YEARS I HAVE BEEN FASCINATED WITH THE PHYSICS OF SOUND, THE IMPLICATIONS OF SEMANTICS AND THE MORE ESOTERIC PATH OF NADA BRAHMA. SINCE I WAS VERY YOUNG, MUSIC HAS BEEN A MAJOR SOURCE OF INSPIRATION. MUSIC BECAME A KIND OF “MEDICINE FOR MY HEART.” I’VE BEEN FINDING THAT REALLY LISTENING TO SOMETHING CAN BE A TYPE OF “YOGA ” IN AND OF ITSELF. SIMPLY DROPPING OUR PREFERENCES, IN ORDER TO LET THE ARTIST SHOW US NEW LANDSCAPES, BECOMES A PROCESS OF STRETCHING AND EXPANDING OUR PERSPECTIVES AND INNER EXPERIENCES. THIS IS ESPECIALLY TRUE WHEN AN ARTIST IMPROVISES. IT IS AMAZING TO LISTEN TO AN ARTIST WHO PUSHES THE BOUNDS OF HIS OR HER PERSONAL EXPERIENCE AND VISION. THIS “RISK TAKING ” DEMANDS BEING IN THE MOMENT.

DO YOU STILL STUDY WITH ZAKIR HUSSAIN? ABSOLUTELY, I WILL ALWAYS BE TAKING LESSONS WITH GURUJI. TO ME, THE FREEDOM AND POWER HE HAS DEVELOPED SEEMS TO HAVE NO LIMIT, EITHER IN THE OUTWARD MUSICAL SENSE OR IN THE INWARD SPIRITUAL SENSE. MY RELATIONSHIP WITH HIM IS ONE OF DEVOTION AND THUS HAS NO SENSE OF BEGINNING OR END. EVERY TIME I SIT WITH HIM, I BECOME A BEGINNER AGAIN. AS A TEACHER, HE IS ABLE TO POINT OUT WEAKNESSES IN A STUDENT’S PERFORMANCE THAT THE STUDENT CANNOT SEE. THIS KIND OF IN-DEPTH TEACHING IS INVALUABLE FOR THE SINCERE STUDENT. MY 15 YEARS OF TRAINING WITH ZAKIR HAVE COMPLETELY CHANGED MY LIFE. IT IS BECAUSE OF HIM THAT I STARTED PLAYING, AND IT IS HIS GUIDANCE THAT INFLUENCED MY DECISION TO MAKE A PROFESSION OUT OF MY PASSION FOR MUSIC. I FEEL VERY BLESSED TO HAVE BEEN TAKEN IN BY HIM. IN MY MIND, WE’VE ONLY JUST BEGUN OUR JOURNEY TOGETHER.

THE INSTRUMENTS OF HINDU MUSIC

VINA

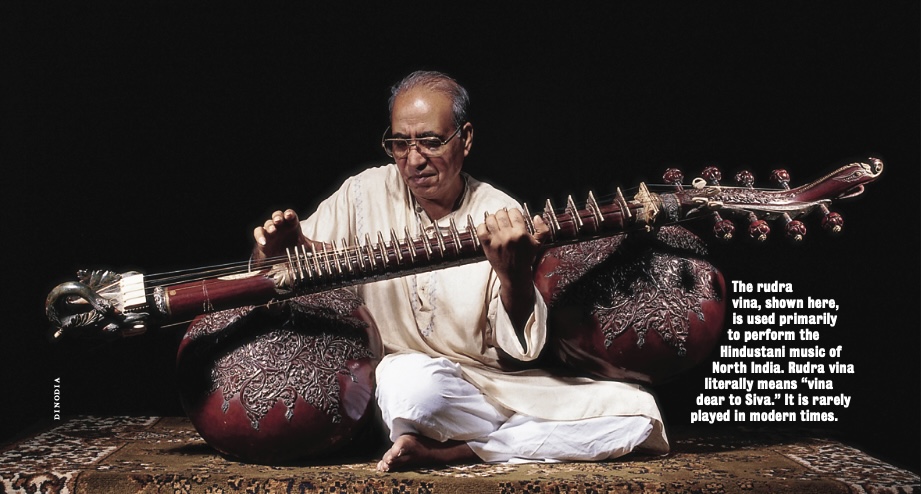

THE VINA (ALSO SPELLED VEENA), A STRINGED INSTRUMENT OF THE LUTE FAMILY, IS USED IN CARNATIC MUSIC. VINA DESIGNS HAVE EVOLVED OVER THE CENTURIES; VARIATIONS INCLUDE THE RUDRA VINA, MAHANATAKA VINA, VICHITRA VINA AND GOTTUVADHYAM (CHITRA) VINA. CURRENTLY, THE MOST POPULAR DESIGN IS KNOWN AS THE SARASVATI VINA. THIS HAS TWENTY-FOUR FRETS; FOUR MAIN STRINGS WHICH PASS OVER THE FRETS AND ARE ATTACHED TO THE PEGS OF THE NECK; AND THREE SUPPORTING STRINGS, WHICH PASS OVER AN ARCHED BRIDGE MADE OF BRASS AND ARE USED AS SIDE STRINGS FOR RHYTHMIC ACCOMPANIMENT. THE VINA IS PLAYED BY SITTING CROSS-LEGGED AND HOLDING THE INSTRUMENT IN FRONT OF ONESELF. THE SMALL GOURD RESTS ON THE LEFT THIGH, WITH THE LEFT ARM PASSING BENEATH THE NECK OF THE INSTRUMENT AND THE LEFT HAND CURVED AROUND SO THAT THE FINGERS CAN PRESS THE STRINGS AGAINST THE FRETS. THE VINA’S MAIN BODY IS PLACED ON THE FLOOR, PARTIALLY SUPPORTED BY THE RIGHT THIGH. SARASVATI, THE GODDESS OF LEARNING AND THE ARTS, IS OFTEN DEPICTED WITH VINA IN HAND, SEATED UPON A SWAN OR PEACOCK.SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.SWARSYSTEMS.COM/INSTRUMENTS/VOLS1.HTM [http:/www.swarsystems.com/Instruments/VolS1.htm]

SITAR

THE SITAR IS PROBABLY THE BEST-KNOWN INDIAN INSTRUMENT IN THE WEST. THIS STRINGED INSTRUMENT HAS BEEN UBIQUITOUS IN HINDUSTANI CLASSICAL MUSIC SINCE THE MIDDLE AGES. THE SITAR BECAME POPULAR IN THE WEST WHEN PANDIT RAVI SHANKAR INTRODUCED INDIAN MUSIC TO THE MASSES, AIDED BY POPULAR ROCK GROUPS SUCH AS THE BEATLES. THE SITAR IS DISTINGUISHED BY ITS CURVED FRETS, WHICH ARE MOVABLE (ALLOWING FINE VARIATION IN TUNING) AND RAISED, SO THAT RESONANT, OR SYMPATHETIC, STRINGS CAN RUN UNDERNEATH THE FRETS. IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE GOURD RESONATING CHAMBER, THIS PRODUCES A LUSH, DISTINCTIVE SOUND. A TYPICAL SITAR HAS 18, 19 OR 20 STRINGS, DEPENDING ON THE STYLE. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.SWARSYSTEMS.COM/DOWNLOADS/INSTRUMENTS/SITAR.MP3 [http:/www.swarsystems.com/Downloads/Instruments/sitar.mp3]

TABLA AND MRIDANGAM

THE TABLA IS A POPULAR INDIAN PERCUSSION INSTRUMENT USED IN THE CLASSICAL, POPULAR AND RELIGIOUS MUSIC OF THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT, PRIMARILY IN HINDUSTANI CLASSICAL MUSIC. IT CONSISTS OF A PAIR OF HAND DRUMS OF CONTRASTING SIZES AND TIMBRES. LEGEND HAS IT THAT THE 13TH-CENTURY MUSLIM PERSIAN POET AMIR KHUSRAU INVENTED THE TABLA BY SPLITTING THE MRIDANGAM INTO TWO PARTS. THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE TABLA FROM A RELIGIOUS-FOLK INSTRUMENT TO A MORE SOPHISTICATED INSTRUMENT OF ART-MUSIC OCCURRED IN THE LATE EIGHTEENTH OR EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY, WHEN SIGNIFICANT CHANGES TOOK PLACE IN THE FEUDAL COURT MUSIC OF NORTH INDIA. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.CHANDRAKANTHA.COM/ARTICLES/INDIAN_MUSIC/TABLA_MEDIA/TABLA.RAM [http:/www.chandrakantha.com/articles/Indian_music/tabla_media/tabla.ram]

THE MRIDANGAM IS A PERCUSSION INSTRUMENT FROM SOUTH INDIA. IT IS THE PRIMARY RHYTHMIC ACCOMPANIMENT IN A CARNATIC MUSIC ENSEMBLE. THE WORD MRIDANGAM IS DERIVED FROM THE TWO SANSKRIT WORDS MRID ( “CLAY ” OR “EARTH “) AND ANG, ( “BODY “). ALTERNATE SPELLINGS INCLUDE MRIDANGA, MRUDANGAM, AND MRITHANGAM. THE MRIDANGAM IS A DOUBLE-SIDED DRUM MADE FROM A PIECE OF JACKFRUIT WOOD, HOLLOWED OUT SO THAT THE WALLS ARE ABOUT AN INCH THICK. THE TWO APERTURES OF THE DRUM ARE COVERED WITH PIECES OF GOATSKIN LEATHER WHICH ARE LACED TO EACH OTHER WITH LEATHER STRAPS. IN ANCIENT HINDU SCULPTURE, ART AND STORY-TELLING, THE MRIDANGAM IS OFTEN DEPICTED AS THE INSTRUMENT OF CHOICE FOR A NUMBER OF DEITIES, INCLUDING LORD GANESHA. NANDI, LORD SIVA’S BULL MOUNT, PLAYS THE MRIDANGAM DURING LORD SIVA’S TANDAVA DANCE. THE MRIDANGAM IS THUS ALSO KNOWN AS DEVA VAADYAM, THE “INSTRUMENT OF THE GODS.” SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.SWARSYSTEMS.COM/DOWNLOADS/INSTRUMENTS/MRIDANGAM.MP3 [http:/www.swarsystems.com/Downloads/Instruments/mridangam.mp3]

SHEHNAI

THE SHEHNAI IS A TUBULAR INSTRUMENT OF PERSIA, SIMILAR TO THE NAGASWARAM BUT SMALLER, THAT GRADUALLY WIDENS TOWARDS THE LOWER END. IT USUALLY HAS BETWEEN SIX AND NINE HOLES AND EMPLOYS TWO SETS OF DOUBLE REEDS, MAKING IT A QUADRUPLE REED WOODWIND. BY CONTROLLING THE BREATH, VARIOUS TUNES CAN BE PLAYED ON IT. THE SHEHNAI WAS CREATED BY IMPROVING UPON THE PUNGI (OR BEEN), THE MUSICAL INSTRUMENT PLAYED BY SNAKE CHARMERS. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.CHANDRAKANTHA.COM/ARTICLES/INDIAN_MUSIC/SHEHNAI.HTML [http:/www.chandrakantha.com/articles/indian_music/shehnai.html]

TAMBURA

THE TAMBURA (SOUTH INDIA) OR TANPURA (NORTH INDIA) IS A LONG-NECKED INDIAN LUTE, UNFRETTED AND ROUND-BODIED, WITH A HOLLOW NECK. THE WIRE STRINGS (FOUR, FIVE OR, RARELY, SIX) ARE PLUCKED ONE AFTER ANOTHER IN A REGULAR PATTERN TO CREATE A DRONE EFFECT. THE LARGER TANPURAS ARE CALLED “MALES ” AND THE SMALLER ONES “FEMALES “. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.SWARSYSTEMS.COM/DOWNLOADS/INSTRUMENTS/TANPURA.MP3 [http:/www.swarsystems.com/Downloads/Instruments/tanpura.mp3]

NAGASWARAM

LOUDER THAN ANY OTHER NON-BRASS INSTRUMENT IN THE WORLD IS THE NAGASWARAM (ALSO CALLED NADASWARAM), ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR CLASSICAL INSTRUMENTS OF SOUTH INDIA. IT IS A LARGE WIND INSTRUMENT WITH A HARDWOOD BODY AND A LARGE FLARING BELL MADE OF WOOD OR METAL. THE NAGASWARAM IS CONSIDERED TO BE HIGHLY AUSPICIOUS, AND IT IS THE KEY INSTRUMENT WHICH IS PLAYED IN ALMOST ALL HINDU MARRIAGES AND TEMPLES IN SOUTH INDIA. THE INSTRUMENT IS USUALLY PLAYED IN PAIRS AND ACCOMPANIED BY A DOUBLE-HEADED DRUM CALLED TAVIL. SOUNDCLIPS: HTTP:/WWW.SAWF.ORG/AUDIO/KALYANI/KARAIKURICHI.RAM [http:/www.sawf.org/audio/kalyani/karaikurichi.ram]

SANTOOR

THE SANTOOR IS A TRAPEZOID-SHAPED HAMMERED DULCIMER OFTEN MADE OF WALNUT, WITH SEVENTY STRINGS. THE LIGHTWEIGHT, SPECIALLY SHAPED MALLETS (MEZRAB), ALSO OF WALNUT, ARE HELD BETWEEN THE INDEX AND MIDDLE FINGERS. A TYPICAL SANTOOR HAS TWO SETS OF BRIDGES, PROVIDING A RANGE OF THREE OCTAVES. LIKE OTHER FORMS OF THE HAMMERED DULCIMER, THE SANTOOR IS DERIVED FROM THE PERSIAN SANTUR; SIMILAR INSTRUMENTS ARE FOUND IN IRAQ, PAKISTAN, ARMENIA, TURKEY AND OTHER PARTS OF CENTRAL ASIA. THE INDIAN SANTOOR IS MORE RECTANGULAR AND CAN HAVE MORE STRINGS THAN THE ORIGINAL PERSIAN COUNTERPART, WHICH GENERALLY HAS 72 STRINGS. THE SANTOOR IS PLACED ON THE LAP WITH ITS BROAD SIDE CLOSEST TO THE BODY. USING BOTH HANDS, THE MUSICIAN LIGHTLY STRIKES THE STRINGS WITH THE MALLETS, SOMETIMES IN A GLIDING MOTION. THE PALM OF ONE HAND CAN BE USED TO GENTLY MUFFLE STROKES MADE WITH THE OTHER. THE RESULTANT MELODIES RESEMBLE THE MUSIC OF THE HARP, HARPSICHORD OR PIANO. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.WORLDMUSICALINSTRUMENTS.COM/UPLOADED/SNTR.WAV [http:/www.worldmusicalinstruments.com/uploaded/sntr.wav]

SARANGI

IN THE HINDUSTANI MUSIC TRADITION, THE MOST IMPORTANT BOWED STRING INSTRUMENT IS THE SARANGI OF NORTH INDIA AND PAKISTAN. OF ALL INDIAN INSTRUMENTS, IT IS SAID TO BEST APPROXIMATE THE SOUND OF THE HUMAN VOICE. CARVED FROM A SINGLE BLOCK OF WOOD, THE SARANGI HAS A BOX-LIKE SHAPE, USUALLY AROUND TWO FEET LONG AND AROUND HALF A FOOT WIDE. THE LOWER RESONANCE CHAMBER IS HOLLOWED OUT AND COVERED WITH PARCHMENT AND A DECORATED STRIP OF LEATHER AT THE WAIST WHICH SUPPORTS THE ELEPHANT-SHAPED BRIDGE–WHICH IN TURN SUPPORTS THE PRESSURE OF APPROXIMATELY 40 STRINGS. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.WORLDMUSICALINSTRUMENTS.COM/UPLOADED/SRGI.WAV [http:/www.worldmusicalinstruments.com/uploaded/srgi.wav]

BANSURI AN VENU

THE BAMBOO FLUTE IS ONE OF THE OLDEST INSTRUMENTS OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC. DEVELOPED INDEPENDENTLY OF THE WESTERN FLUTE, IT IS SIMPLE AND KEYLESS; SLIDING THE FINGERS OVER THE HOLES ALLOWS FOR THE ORNAMENTATION SO IMPORTANT IN RAGA-BASED MUSIC. THERE ARE TWO MAIN VARIETIES OF INDIAN FLUTES: THE BANSURI, WITH SIX FINGER HOLES AND ONE BLOWING HOLE, IS USED PREDOMINANTLY IN HINDUSTANI MUSIC; AND THE VENU OR PULLANGUZHAL, WITH EIGHT FINGER HOLES, IS PRIMARILY USED IN CARNATIC MUSIC. SOUNDCLIP: HTTP:/WWW.CHANDRAKANTHA.COM/AUDIO/BHAJANS/SHIVA_SHANKAR.RAM [http:/www.chandrakantha.com/audio/bhajans/shiva_shankar.ram]