BY GAJANAN NATARAJ

I am a Saint Lucian citizen. i was born in the US Virgin Islands and lived briefly on the mainland (USA), but for the better part of 23 years I was raised on the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia. I am roughly two-quarters Indian and two-quarters Negro–meaning both my parents were themselves of mixed heritage. This is common in Saint Lucia. We are called dougla–which comes from doogala (“two necks”), a demeaning label meaning mixed race or half-caste in Bhojpuri and Hindi. In Saint Lucia, the term is sometimes used affectionately, sometimes not so affectionately.

Though many on the island are of Indian heritage, I am one of the very few Hindus. I have a Hindu name, perform daily puja to Lord Ganesha and consider the cow a sacred creature. I believe in karma, dharma, reincarnation, the divinity of the Vedas and in the need for a satguru to guide my spiritual journey. Of all the Indian families who came to Saint Lucia from Kolkata as indentured workers in the 19th century, mine is one of the few to reclaim our Hindu heritage. In being Hindu, I am almost unique among the fifth generation of Indian immigrants. Even among my close relatives, almost all are Christians.

How did I come to be a Hindu in a land where Christianity reigns supreme, even among Indians? I attribute my discovery of this beautiful religion to the interplay of my soul’s natural calling and God’s blessing of being born to parents who are ardent seekers of spiritual truth. Indeed, my growth from non-religious, Christian-influenced spiritual confusion can only be credited to the marvelous journey of my parents.

It was really my mother, Toshadevi (Mangal) Nataraj, who never gave up her search for her spiritual roots and who eventually led my entire family back to the Sanatana Dharma. She is half Indian, in the fourth generation; her Hindu ancestors came to the island in 1862 on the second ship of indentured laborers. Raised by her Indian father, Reese Mangal, she was exposed to those few Indian traditions that were still practiced on the island in the 1960s. She remembers her grandfather, Gaillard Mangal, as tall and dark, always singing bhajans, even though he had a Christian name. Most Indians of the time were at least nominal Christians, a result of coercive strategies by the churches [see sidebar opposite].

Gaillard spoke the local French Creole, but also spoke some Hindi, as his parents were first-generation Indians. His wife, my great-grandmother, was given the Christian name Charlotte. She is remembered as a strict, light-skinned woman, quite serious about following tradition, especially the funeral rites. On the one-year anniversary of a relative’s transition, she would make sure the family did the shraddha ceremony. A shrine was set up to the departed, their favorite foods cooked and left for them. Separately, the family would have food served on banana leaves on the floor, eating with the fingers–apparently the only time they would eat in this Indian fashion. My mother says the locals of African descent would sometimes mock these Hindu rituals.

One of my mother’s vivid memories about her grandmother was the shrine she kept on the family land, with an oil lamp, a statue of the Virgin Mary and a small murti of Ganesha. My great-grandparents may have been devotees of the Goddess Durga, worshiping the Divine Mother through the image of Mary–an eclectic blend of Hindu religion and the imposed practices of Christianity. Every family member had an Indian name, my mother says, but these could not be used in school. Consequently the European names, such as Gaillard and Charlotte, stuck with them.

At age 11, my mother had to be baptized as a Catholic to enter the only all-girls secondary school on the island–the top performing academic institution, not only then but to this day. She says she never felt any connection to the Christian teachings. She often asked herself, “Why was I born half Indian–in a sort of limbo between the quite-different cultures of St. Lucian’s Indians and Africans?” She committed herself to finding the root of her Indian heritage. She was encouraged by the example of my grandfather’s sister “Joyce,” who had returned to India, settled and raised a family, and was living as a Hindu.

My mother left home at age seventeen to live in the US Virgin Islands with her mother, a strong woman of African descent. Even though a Christian, her mother had many books on yoga and Indian philosophy. Reading those tomes, my mother slowly gained a new perspective and began to realize the beauty of the culture that her people in Saint Lucia had virtually lost. But it was difficult to find a path back to pure Hinduism. Again and again she was told the myth–even by some Hindus–that “you have to be born a Hindu to be a Hindu.” She eventually joined a universalist religious group, attracted by their worship–albeit Christian in nature–of Lord Ganesha, Krishna, Siva and the Divine Mother. Their core teachings included karma, reincarnation and yoga.

Meanwhile, my father, whose background had more influence from the African side, was on his own spiritual journey. In his search for truth, he joined a raja yoga group in Trinidad where he learned more about Hinduism. He and my mother eventually ended up in the same universalist movement, where their paths merged. Several years after they got married, they left the group and continued their spiritual search on their own.

Because of my parents’ continuing quest, my two sisters and I were raised with an inherent acceptance of the basic Hindu beliefs, such as the laws of karma and reincarnation, as well as an understanding of the Supreme God’s ability to manifest in multiple forms. Therefore, we were never limited by the Abrahamic concept of “only one way” that pervades Saint Lucian society, in particular the education system.

In 2002, my mother discovered the teachings of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami through his book Loving Ganesha. The truths of Saivite Hinduism appealed to us all and were easily understood and accepted. We had found our spiritual path, Hinduism, the Eternal Faith.

Satguru Subramuniyaswami had attained Mahasamadhi in 2001, but we contacted his monastic order at Kauai’s Hindu Monastery (home of Hinduism Today) and sought the advice of his successor, Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami. We then began formal study under his guidance.

In 2010 Bodhinatha briefly visited Saint Lucia and came to our home. The local Hindu community turned out in large numbers to greet him. Consisting primarily of Indians who had come to the island in the last thirty to fifty years, the Hindu community has always been welcoming and supportive of my family. They have assisted with our home ceremonies, including my youngest sister’s coming-of-age ceremony, the ritu kala samskara.

In 2011, after several years of study, I formally entered Hinduism through the namakarana samskara, the name-giving rite, on Kauai island in Hawaii.

In 2012, I came back to Kauai for the monastery’s six-month Task Force program, which includes helping the staff of Hinduism Today. That is how I came to be writing this article, with the blessings of Lord Ganesha, to shed some light on the status of Hinduism in Saint Lucia and possibly many other Caribbean Islands.

Today I continue my studies of Saiva Siddhanta. I am working hard to become a formal shishya of Satguru Bodhinatha. My family practices Hinduism, and we adhere as best we can to all of the traditions.

Richard Cheddie said it well: “Imagine that the last shipload to arrive was only 112 years ago. There are still St. Lucians alive today whose parents came from India. There are a few that still speak some Hindi (Oudh/Bhojpuri dialects), some that still sing the old songs and some that still have knowledge to pass on. In my visits to Africa, the Middle East, Europe and North America I have seen much of the strength of many people who have held on to their culture, some for thousands of years, despite what conquerors have tried to do to strip them of their beliefs.”

My name is Gajanan Nataraj, and I am proud to be a Hindu. I am proud to be Saint Lucian. And I am exceedingly grateful to be a Hindu man in Saint Lucia, with profound truths of culture, faith, philosophy and selfless devotion to pass on to the next generation of Saint Lucian Hindus.

SAINT LUCIA’S HINDU HISTORY

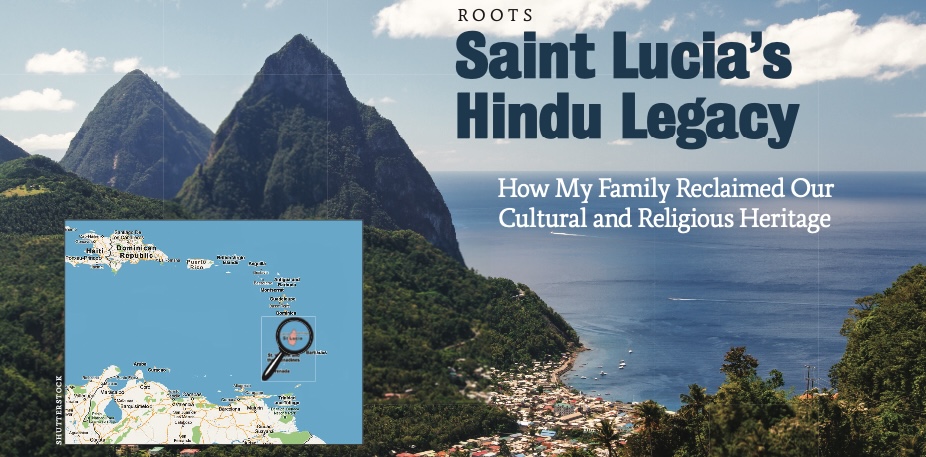

Saint lucia is a volcanic caribbean island of just 238 square miles, originally inhabited by Amerindian tribes. In the 17th century both France and England coveted its natural harbor, Castries. They fought fourteen battles over it, the island changing hands after each one. The British won final control in 1814. Today Saint Lucia is an independent nation with a population of 176,000 and is a member of the British Commonwealth.

The Europeans had established sugar cane plantations in the 17th century, using slave labor. When slavery was abolished in 1838, the freed slaves refused to work the plantations. The British responded by bringing indentured workers from India.

According to Saint Lucian genealogist Richard Cheddie (whose name is likely derived from Chedi), thirteen ships carrying indentured laborers were brought from East India, with the first ship, the Palmyra, arriving in 1859. The Indians who came on these ships called themselves Jahajis (seafarers) and developed significant bonds during their journey to the Caribbean. Many of their decendants remain close to this day.

Cheddie’s research indicates that when the Indians first came to British-ruled Saint Lucia, they were able to continue their traditions without much opposition from either the Christian British authorities or the Africans who had been converted to Christianity. The Indians wore traditional clothing, celebrated Deepavali and settled disputes using the Indian village panchayat system.

In the late 19th century, the local Christian churches began work to convert the Hindus. They realized, however, that Hinduism was deeply ingrained. It was more than just religious practice; it pervaded all customs, values and traditions of the Indians. A cunning and effective strategy was therefore crafted.

The Catholics ran most of the schools. They decreed that in order for Indians to enroll, they first had to convert to Christianity. Initially, this was resisted, but eventually many gave in. Securing work away from the sugar plantation required a formal education.

The convert was pressured to use his “Christian” name exclusively. As a result, there are many Indian clans on the Island with surnames like Joseph, MacDoom and Ragbill. Many names also became Anglicized or Gallicized (made to sound French). As a result, Bihari became Beharry. Shripal, a name of Vishnu, became Cepal; Kanhaiya, a name of Krishna, became Canaii. Some names suggest a place of origin. Ajodha, for example, is from Ayodhya, the birthplace of Lord Rama. Other names retained their Indian spelling but were pronounced in an English way. So, a name like Kadoo was pronounced, “Kay-Doo.” For a long time, a Christian priest was required for the name-giving process. As recently as the 1990s, some refused to register names associated with Hindu Gods and Goddesses.

Even more critically, according to Cheddie, “A couple married in the Hindu custom had no rights as far as the law was concerned”–the same policy Gandhi protested in South Africa. Moreover, those who had converted to Christianity were told it was now their duty to marry another Christian–a task complicated by the sectarian divisions within the Christian community itself! Even clothing was a target, with Indians being required to dress “appropriately” for work, which meant no traditional clothing. Among those who remained Hindus, Cheddie tells us, traditions such as the telling of stories from the epics were discouraged. Eventually many Indians joined the Seventh-day Adventist Christian church, since its family- and community-oriented approach to religion reflected their own cultural values. Many remain members today.

Not only the English but also those of African descent scorned Indian culture in the early years. They ridiculed Indians as weak and uneducated–and continued to do so even after many had become wealthy and their children excelled in school.

Most Indians who came to Saint Lucia during plantation times either went back to India after their five-year contracts were up, or moved to other Caribbean islands with larger Indian populations. Now, 152 years after the first Indians arrived, the religion and culture have been largely eroded. There is little racial tension, mostly because nearly everyone is a Christian. A recent new influence is the arrival of many students from India to attend the local medical universities, as well as Indian entrepreneurs, doctors and technicians.

HINDUISM IN SAINT LUCIA TODAY

By Gajanan Nataraj, Saint Lucia

It’s a sad thing when little Ravi and Nalini Gajadhar have no clue as to the significance of their beautiful names. They likely never heard the words mandir, Sanskrit, Bharat, shanti, dharma or even the sacred syllable Aum. They may have been told that their names are of Indian origin, but the Hindu element of this part of their identity has been virtually lost. This is the lamentable cultural condition of at least one hundred of Saint Lucia’s present-day Indian clans.

Many Saint Lucians of African descent have come to realize that, while nothing is wrong with practicing Christianity, they were actually robbed of their African heritage, culture and most importantly, religion. Many have re-embraced whatever remains of African culture within and around them and now seek to bring back the ancient values and traditions of their motherland to their Western home in the Caribbean. Our Saint Lucian Indian families have yet to catch on to the realization that our heritage is more than just a racial or ethnic concept. It is also a spiritual wealth that all descendants of India should at least know of.

In spite of the apparent absence of Hinduism in its splendor on our little island, the Sanatana Dharma is still present in enticing glimmers here and there. Indians on the island are still very family-oriented at their core and generally take care of their own. Businesses are often handed down from father to son, just as was done in India before the infiltration of modern, individualistic Western thinking. The Indians have integrated quite well in society, overcoming the racial tensions between themselves and the Africans. Many “black” people can trace their roots back to at least one Indian ancestor, a major factor in the virtual absence of racial tension on the island.

In recent years, some descendants of the original Indians, myself included, have shown a growing interest in reclaiming their heritage and reconnecting with Indian traditions. My friend and fellow Indo-Caribbean history enthusiast, James Rambally, has done a lot of work on the island to raise awareness of an “Indian Identity.” He has independently educated himself in long-lost traditions.

Recently a young local Indian couple opted to have a traditional Hindu wedding [see photo right] in addition to a Christian ceremony–possibly launching a new trend. It was inspiring to see none other than Lord Ganapati Himself on the wedding invitation.

An even more inspiring story is that of a local Indian woman who told me she had a vision of Lord Krishna telling her that He was God. She was deeply inspired, and although her friends and family members ridiculed her, she would not be deterred. She returned to India as a third- or fourth-generation Indian, studied and learned the beauty of Vaishnava Hinduism, then came back to Saint Lucia and married. She and her husband, of African descent, opened a Jaganatha Temple affiliated with ISKCON in the south of the island. Their story has always served as a source of inspiration for me.

There are a few other Hindu groups on the island. Devotees of Sri Satya Sai Baba have a local satsanga group that meets monthly, embracing all Hindus and even non-Hindus. The Sanatan Hindu organization recently brought a Hindu teacher from Europe, but it’s rare for any Hindu leaders to visit our small island. The main way one can learn more about Hinduism is by drawing close to the small community of practicing Hindus–mostly recent arrivals from India.

The government is starting to take notice of this resurgence in Hinduism. In 2010, with the aid of the Brahma Kumaris of Trinidad, my family, along with two other families from India and Guyana, represented Hinduism at a government-sponsored “National Day of Prayer” interfaith event.

In exploring one’s Hindu roots, one encounters the question of how to re-enter the religion. In school we’re taught that Hindus don’t accept converts, and even some Indian teachers have said the same. I know now it is possible. In fact, organizations such as the VHP and the Arya Samaj actively convert people to Hinduism–especially those like us who come from Hindu ancestors.

I look forward to seeing more Indo-Saint Lucians courageously reconnecting to their Hindu roots. Maybe in the years to come, the large Indian settlements like Forestiere will be home to one or two Hindu temples for future generations who are drawn to the beauty of their Indian/Hindu heritage.

Love this article. Would love to connect with writer and others.

Ramji.

Thanks for St. Lucia connection.

Read details of Hindu history in St. Lucia.

Hope to connect.

Thanks.

I was born in st. Lucia but live in NYC. I had an Indian girlfriend in st. Lucia in the 90s that I lost touch with but after over 20 years I can’t get her out of my head. Her name was Mandy and I swear she is the one that got away. Glad you held on to your traditions. I swear I will come home to find my indian wife. O happen to be black but fascinated with the culture and beauty of Indian women.