INFLUENCE

CHAMPIONS OF NONVIOLENCE

______________________

How men and women committed to Gandhian tactics changed our world for the better

______________________

BY MARK HAWTHORNE, CALIFORNIA

THERE ARE IN THE WORLD MANY PEOPLE who have fought great battles for social or political justice using the principles of Mahatma Gandhi. Five among them stand out strongly: Martin Luther King, leader of the American civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s; Nelson Mandela, who brought an end to apartheid in South Africa; the Dalai Lama, who seeks a peaceful resolution on Tibet; Aung San Suu Kyi, who fought for democracy in her native Myanmar (Burma); and César Chávez, who struggled to reduce exploitation of farm workers in California. Four of these—King, Mandela, the Dalai Lama and Suu Kyi—were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. All proudly acknowledged their debt to Gandhi.

To be equated with Mahatma Gandhi is to be instantly aligned with a distinct set of ideals, for the name resonates for anyone who believes in truth, independence and nonviolence. Although ahimsa literally means “noninjury,” Gandhi’s use of the word encompassed universal love. According to the Mahatma, to follow the doctrine of ahimsa means you may not offend anyone; you may not harbor an uncharitable thought, even of your enemy. Indeed, the man who follows ahimsa has no enemies. “A man cannot then practice ahimsa and be a coward at the same time,” he wrote. “The practice of ahimsa calls forth the greatest courage.”

Gandhi died at the hand of an assassin in 1948, the year after India gained its independence from Britain, largely due to his efforts. His achievements had become known around the globe, encouraging world leaders that, yes, nonviolence could indeed be effective in creating change, if you had the courage and fortitude to follow such a path.

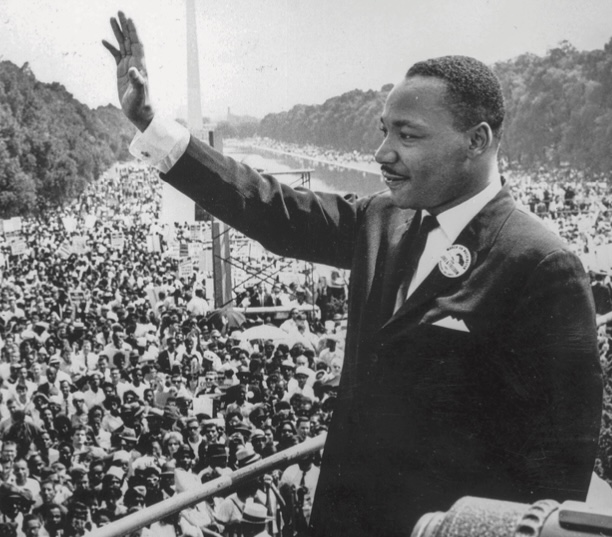

Martin Luther King, Jr.

One leader to heed that call was Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. This young Black minister rose to prominence in America during the civil rights movement in the 1950s, when racial tensions had escalated and demonstrations swelled for voting rights and school integration. America was segregated, with African Americans and other groups of color subjected to political and economic disenfranchisement. Violence against them was commonplace, especially in the South.

In the 1940s, King was a seminary student who despaired that love could ever be an effective tool for social reform. Then Gandhi’s writings changed his thinking. He learned how Gandhi had used ahimsa to help India gain independence from its British oppressors. Why, King thought, couldn’t this same policy work for the African American in his struggle to abolish segregation and be treated as an equal among whites?

King was able to put his newfound philosophy to the test in 1955 when he was elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association and began leading the city’s bus boycott against segregated buses where the Blacks had to sit in the back. As the nonviolent protest took root, and bus ridership in the city dropped 90 percent, King’s home was bombed and he suffered many of the same abuses Gandhi had. King rallied the protesters with the words of Mahatma Gandhi: “Rivers of blood may have to flow before we gain our freedom, but it must be our blood.” The eleven-month struggle led all the way to the US Supreme Court, which declared segregation on buses unconstitutional.

King’s victory brought him international recognition, and he was called “the American Gandhi.” Now filled with hope, the reverend made a pilgrimage to India in 1959 to speak with those who knew and worked with Gandhi. King, his wife Coretta and educator Lawrence Reddick landed in Bombay on February 9, arriving in New Delhi the following day. He told reporters at the airport: “To other countries I may go as a tourist, but to India I come as a pilgrim.”

At a state dinner with India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, King was full of questions about Gandhi’s philosophy and adherence to ahimsa. Nehru’s answers focused on Gandhi’s political acumen, leaving King to seek out Gandhi’s spiritual successor, Vinoba Bhave, an ardent Gandhi follower who carried on the Mahatma’s efforts for a just and equitable society. Born into a devout brahmin family, Vinoba appreciated the spiritual dimension of Gandhi’s vision. He understood that Gandhi aimed at more than independence from Britain—he envisioned a wider goal: Sarvodaya, a nonviolent society dedicated to “the welfare of all.” In 1940, Gandhi selected Vinoba to initiate a great campaign of civil disobedience in his struggle against the British. He was arrested and spent five years in prison. When King caught up with him in 1959, Vinoba was engaged in a campaign he called the Bhoodan (“gift of land”) movement, traversing India on foot, asking rich landowners to donate one-fifth of their land to the poor. By 1954 the donations had grown to 2.5 million acres, far exceeding any land reform achieved by the government.

During his time in India, King felt very much at home. Their overlapping experiences with racism and common philosophy of liberation sparked numerous conversations between King and the Indians he met. He spoke before university groups and at public gatherings, which were always well attended. “We were looked upon as brothers, with the color of our skins as something of an asset,” he later said. “But the strongest bond of fraternity was the common cause of minority and colonial peoples in America, Africa and Asia struggling to throw off racism and imperialism.”

Indian papers had carried news of the Montgomery bus boycott, and Gandhians praised King for his adherence to ahimsa. To them, as to King, it suggested that nonviolent resistance could effectively work even under a totalitarian regime, such as in South Africa. King and a group of Gandhians even found themselves arguing this point with a group of African students who were studying in India. The students believed that nonviolent resistance could only work if the opponent had a conscience. King, along with others, explained the differences between passive resistance and nonresistance. “True nonviolent resistance is not unrealistic submission to evil power,” King said. “It is rather a courageous confrontation of evil by the power of love, in the faith that it is better to be the recipient of violence than the inflicter of it, since the latter only multiplies the existence of violence and bitterness in the universe, while the former may develop a sense of shame in the opponent, and thereby bring about a transformation and change of heart.”

It had taken India almost half a century to gain independence, and therefore it was unrealistic to expect immediate gains in the US. King returned to America with an appreciation for Gandhi’s patience and a greater determination to achieve freedom for African Americans through nonviolent means. From the pulpit in Atlanta, King cited Gandhi’s denouncing the practice of untouchability to illustrate it is better to criticize ourselves than our enemies. Martin Luther King, Jr. received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and continued his nonviolent struggle until 1968 when, at 39 years old, like Gandhi, he was shot dead by an assassin.

Dalai Lama

The same year King went to India, 1959, a Tibetan uprising was brutally suppressed by the Chinese, and Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, fled to India. The Dalai Lama had been to India three years earlier to celebrate the Buddha’s 2,500th birthday. Like Martin Luther King, Jr., he had sought out Gandhians to learn how India had achieved independence through nonviolence. Concerned about the survival of Tibetans and the country’s unique heritage, the Dalai Lama has not called for the outright independence of Tibet or its separation from China. His “Middle Way Approach” seeks genuine autonomy for Tibet, eliminating direct rule from Beijing and giving it the right to maintain its culture, language and religions while remaining part of China.

The Dalai Lama’s Middle Way Approach and lifelong dedication to nonviolence were recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. In his speech to the Nobel committee, the Dalai Lama said, “I accept the prize as a tribute to the man who founded the modern tradition of nonviolent action for change—Mahatma Gandhi—whose life taught and inspired me.”

Nelson Mandela

The Dalai Lama acknowledges Gandhi as his mentor but calls fellow Nobel Laureate Nelson Mandela of South Africa the Mahatma’s successor as a savior of humanity through his struggle for peaceful change. “The [21st century] should be one of dialogue and peace,” he said after meeting Mandela. “In the past Mahatma Gandhi was a very good example of this and now you [Nelson Mandela] are a great successor of that person.”

Nelson Mandela, then a young and successful lawyer, became active in the anti-apartheid movement in the 1940s. He warned demonstrators of the difficulties they would face and urged them to refrain from violence. When Mandela and another lawyer opened their own practice in 1952, the first black legal firm in the country, they were inundated with African clients, many of them victims of the apartheid system. Mandela used the courts to good advantage, challenging white authority and building his reputation in the fight against discrimination.

As the 1960s approached and South African authorities used more and more violence to crack down on the anti-apartheid movement, Mandela shifted his approach from civil disobedience to sabotage. “I followed the Gandhian strategy for as long as I could,” he later wrote, “but then there came a point in our struggle when the brute force of the oppressor could no longer be countered through passive resistance alone. Even then, we chose sabotage because it did not involve the loss of life, and it offered the best hope for future race relations.”

Mandela was arrested in 1962 and later sentenced to life imprisonment for sabotage, making him an international symbol of struggle against apartheid. After 27 years, he was released from prison in 1990, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 and became the first president of post-apartheid South Africa the following year.

Aung San Suu Kyi

About the time that South African politicians were transforming racial discrimination into apartheid, Burma, part of British India for a century, was granted independence. But the transition proved violent, and in a short time Burma (now Myanmar) was ruled by a military junta.

Aung San Suu Kyi, a graceful and slight woman of 68, has become the symbol of nonviolent protest in Myanmar. Struggling against a tide of brutal suppression of pro-democracy campaigns, she has remained true to the ideals of Gandhi who, she said, “demonstrated to the world the supremacy of moral force over force based on the might of arms or empire.”

Born in Burma, Suu Kyi is the child of assassinated Myanmar independence hero General Aung San, who led the struggle for the country’s independence. Suu Kyi spent much of her youth in New Delhi, where her mother was serving as Burma’s Ambassador to India. It was there that Suu Kyi learned about Mahatma Gandhi. In 1964 she enrolled in Oxford University, where she studied philosophy, politics and economics.

When she returned to Burma in 1988, she spoke out against the military rule. As the daughter of a national hero and an ambassador, she was not someone the junta could simply lock away in prison. She was put under house arrest until 1995.

Aung San Suu Kyi has built a platform on four themes: 1) The restoration of human rights, 2) Nonviolent means to achieve these rights, 3) The problem of human rights has arisen because the military usurped power from the government, and 4) All opponents of the military dictatorship must not actively provoke the military to do anything except lay down its arms.

The military still ruled with an iron fist until a constitutional referendum was held in 2008, resulting in elections in 2010 and dissolution of the junta the following year. Today, Suu Kyi holds office in the Burmese lower house and leads the National League for Democracy, which she helped found.

César Chávez

The most unlikely of our Gandhians is César Chávez. At age 21, he watched the newsreels announcing that Gandhi had defeated the British Empire without the use of force. He wondered how Gandhi could have accomplished such a feat. Born in Arizona in 1927 to a family of migrant farm workers, Chávez saw firsthand how Mexican Americans were segregated and treated differently from whites. Chávez read Gandhi’s autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Chávez went on to read everything he could find about Gandhi, whose belief in self-sacrifice and self-discipline were values Chávez could understand. He was especially impressed by Gandhi’s commitment to ahimsa.

Leadership: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in his home town of Porbandar, Gujarat, in August of 1942

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Chávez found in Gandhi’s life hope and encouragement for his own struggle against the exploitation of Mexican, Mexican-American, Filipino and African-American migrant agricultural workers, who comprised the majority of farm laborers in the United States. Performing backbreaking work in harsh conditions, these workers were sometimes thought of—and treated—as slaves by growers.

With Gandhi as his guide, Chávez began a workers’ rights movement that used marches, boycotts, strikes and civil disobedience to bring attention to farm-work conditions. Chávez told volunteers and picketers during a strike against grape growers in California: “If someone commits violence against us, it is much better—if we can—not to react against the violence but to react in such a way as to get closer to our goal. People don’t like to see a nonviolent movement subjected to violence, and there’s a lot of support across the country for nonviolence. That’s the key point we have going for us. We can change the world if we can do it nonviolently.”

In 1962, Chávez established the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW). Chávez traveled from camp to camp organizing the workers. He felt the growers’ use of pesticides was one of his strongest and most critical platforms, and one that would also concern the consumer. The union began a boycott of table grapes in 1965, picketing farms and disseminating information about pesticide use. The growers hired illegal workers and brought in strikebreakers to beat up the strikers. Union members, Chávez included, were jailed repeatedly.

Again taking a cue from Gandhi, Chávez went on fasts to gain attention for the cause, going without food for 25 days in 1968 when he saw the grape boycott losing ground. He would fast for 36 days in 1988. Sympathetic to Chávez and the union’s cause, religious leaders, public officials and others from across America traveled to California to march in support of the farm workers. After five years of protests, some grape growers signed agreements with the union, and they lifted the grape boycott.

By the early 1980s, the tens of thousands of farm laborers working under UFW contracts enjoyed higher pay, family health coverage, pension benefits and other contract protections. Chávez died in his sleep in April, 1993. Having never earned more than $6,000 a year and never owning a house, Chávez could only leave behind his legacy of nonviolence and commitment to human rights. As he put it: “Once people understand the strength of nonviolence—the force it generates, the love it creates, the response it brings from the total community—they will not easily abandon it.”

Gandhi’s example transcended color and politics. Dedicated to human rights and not willing to debase themselves through violence, leaders like King, the Dalai Lama, Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi and César Chávez saw that ahimsa is more powerful than armed protests. In a tribute to his mentor in a 1998 edition of Asiaweek, the Dalai Lama eloquently characterized Gandhi’s gift to the world. “If we are to think of the 20th century as one of Asian liberation,” he wrote, “Mahatma Gandhi naturally stands out as a beacon of inspiration. Drawing on the thoughts of India’s great teachers of the past, he employed the ancient but powerful idea of ahimsa, or nonviolence, in a fresh, dynamic and effective way. A great man with a deep understanding of human nature, Mahatma Gandhi made every effort to encourage the full development of the positive aspects of our human potential and to reduce or restrain the negative. Consequently, he showed by example that personal liberation is integral to the successful achievement of national liberation.”

GANDHIANS ON GANDHI

______________________

Five leaders who prevailed with the spirit of nonviolence

______________________

His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet: “The place of Gandhi’s cremation was a calm and beautiful spot. I felt very grateful to be there, the guest of a people who, like me, had endured foreign domination, grateful also to be in the country that had adopted ahimsa, the Mahatma’s doctrine of nonviolence. As I stood praying, I experienced simultaneously great sadness at not being able to meet Gandhi in person and great joy at the magnificent example of his life. To me, he was—and is—the consummate politician, a man who put his belief in altruism above any personal considerations. I was convinced, too, that his devotion to the cause of nonviolence was the only way to conduct politics.”

Nelson Mandela, first president of post-apartheid South Africa: “Gandhi remains today the only complete critique of advanced industrial society. Others have criticized its totalitarianism, but not its productive apparatus. He is not against science and technology, but he places priority on the right to work and opposes mechanization to the extent that it usurps this right. Large-scale machinery, he holds, concentrates wealth in the hands of one man who tyrannizes the rest. He favors the small machine; he seeks to keep the individual in control of his tools, to maintain an interdependent love relation between the two, as a cricketer with his bat or Krishna with his flute. Above all, he seeks to liberate the individual from his alienation to the machine and restore morality to the productive process.”

Aung San Suu Kyi, founder of Burma’s National League for Democracy: “The life and works of Gandhiji, as I was taught to refer to him even as a child, are both thought-provoking and inspiring for those who wish to reach a righteous goal by righteous means. I would like to focus on two short comments by Gandhiji on compulsion and discipline. In the April 17, 1930, issue of Young India he wrote: ‘We may not use compulsion even in the matter of doing a good thing. Any compulsion will ruin the cause.’ Gandhiji further wrote in the December 20, 1931, issue of the same publication, ‘We cannot learn discipline by compulsion.’ These simple statements reach to the very heart of our attempts to build a strong and united Burma based on the consent and goodwill of the people.”

César Chávez, founder of United Farm Workers: “Gandhi is an example. He showed us not by talking, not by what he wrote as much as by his actions, his own willingness to live by truth, and by respect for mankind and accepting the sacrifices. You see, nonviolence exacts a very high price from one who practices it. But once you are able to meet that demand then you can do most things, provided you have the time. Gandhi showed how a whole nation could be liberated without an army. This is the first time in the history of the world when a huge nation, occupied for over a century, achieved independence by nonviolence. It was a long struggle, and it takes time.”

Martin Luther King Jr., minister and civil rights activist: “Gandhi was inevitable. If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, thought and acted, inspired by the vision of humanity evolving toward a world of peace and harmony. We may ignore him at our own risk.”