Mirabai’s Soulful Love of God

The Life and Legacy of a Poet-Saint

BY LAKSHMI CHANDRASHEKAR SUBRAMANIAN & MARIELLEN WARD

“It is extremely difficult to find a parallel to this wonderful personality, Mira, a saint, a philosopher, a poet and a sage. She was a versatile genius and a magnanimous soul. Her life has a singular charm, with extraordinary beauty and marvel.” Swami Sivananda

The most popular songs of Mirabai speak of her unflinching love for Lord Krishna, attempts to poison her, the miraculous escape and her blissful merging with God. Mirabai (c.1498–c.1557) was a remarkable Hindu devotional poet-saint in 16th-century India. She was a princess born in the town of Merta and married to a king in the Mewar region, both in the northwestern Indian state of Rajasthan. Twentieth-century Indian cinema has portrayed this in several accounts. Mirabai, also known simply as Mira, is a favorite among Hindu poet-saints, particularly in the North Indian bhakti tradition, and thousands of poems have been attributed to her. Saint Nabhadas of the early 17th century praised her in his hagiography, “Renouncing respect in society and all family ties, Mira worshiped Lord Krishna in the form of the divine mountain-lifter Giridhari.” Entitled Shribhaktamal (“garland of devotees”), Nabhadas’ anthology, comprising descriptions of numerous bhaktas and one of the oldest Indian vernacular hagiographies, contains six meaningful lines about Mirabai. The central message is that of her fearless devotion to Giridhari in the face of familial and societal obstacles. This early mention of Mira, in addition to her large poetic corpus, carves a well-defined place for the saint in the “bhakti movement,” a spiritual revolution in India lasting several centuries during which there was a fervent attempt to make religion accessible to all, irrespective of language, gender or caste. A Google search fetches numerous popular Mirabai songs translated into English by Hindu organizations, secular poetry websites and academic scholars. The Western interest in Mirabai started with British colonialists in the early 19th century; and since then there have been several translations of her songs. Immigrant communities as well as academicians carried the baton forward. Today Mira’s songs are found everywhere, from well-attended Mirabai Festivals to informal music sessions at yoga studios. In the 21st century, Mira has surpassed her standing as a pan-Indian devotee to become a global poet-saint revered by an international audience. In the pages to follow, her dramatic life story is unraveled and the path she took in life is documented, along with temples and museums that honor her life. Her linguistic genius and depictions of her life in film and the digital world are also explored.

Mira’s Bhakti Poems

By Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian

DEVOTIONAL POETRY IS NOT ISOLATED LITERATURE; IT IS CONNECTED to systems of spiritual practice, or sadhana, such as singing, chanting, prayer—undertaken individually or as a community. These practices evoke devotion in the heart of a spiritual aspirant. The uniqueness of Mira’s poems is that they have traveled throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond, not as texts but as songs traveling on the tongues of people performing various types of personal sadhana. Mira sang:

I have obtained the precious wealth that is the Lord!

This invaluable treasure is from my true guru.

Out of compassion, he has given this to me.

I have obtained the asset of many lifetimes

and lost everything of this world.

Doesn’t reduce with spending, that which no thief can steal.

It increases day by day (by a quarter).

On the boat of truth, with my true guru as the boatman,

I have crossed the ocean of endless births and deaths.

Mira’s Lord, the clever mountain-lifter

With much happiness I sing his glories.

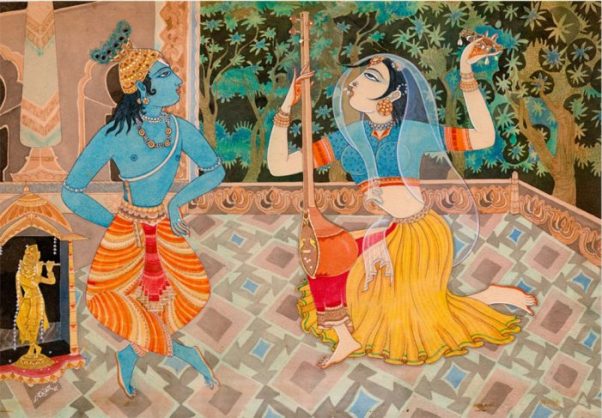

Vibrant today: Krishna (Giridhari) lifts Mount Govardhan to protect His gopis from Indra’s wrath

Mirabai composed sagun poetry, songs about a personal God with particular attributes and personality traits (sagun: sa “with,” guna “attributes”). In her case, divinity is embodied in Giridhari, the heroic form of Krishna as mountain-lifter. Based on signature line (chhaap) and the oral tradition that this song has passed through over the centuries, we can be confident that Mirabai composed this poem. Sentence structure is confusing. The base lyrics, paayoji maine, is the starting point, which gets transformed into a musical piece with context-specific elements such as melody, tempo, orchestration and performance setting. The underlying emotion (bhava) in this poem is ecstatic devotion and contentment; Mira joyfully sings about having obtained the greatest wealth, which is the Lord. Over time, countless musicians have performed this poem—at temples, concert halls and home altars. More recently, it has been featured in a Bollywood film. “The base lyrics, paayoji maine, is the starting point, which gets transformed into a musical piece with context-specific elements, including melody, tempo, orchestration and performance setting.”

Bhakti, or devotion, comes in many flavors and causes a devotee to completely forget herself. According to some Hindu schools of thought, five kinds of emotions 00can arise in bhakti: shanta, dasya, sakhya, vatsalya and madhurya. These bhavas arise in one’s heart subconsciously, and one should go towards whatever resonates with his or her temperament. Mirabai’s poetry falls under madhurya bhava, as she thought of the Lord as her beloved. In Swami Sivananda’s words, “The lover and the beloved become one. The devotee and God feel one with each other and still maintain a separateness in order to enjoy the bliss of the play of love between them. This is oneness in separation and separation in oneness. Lord Gauranga, Jayadeva, Mira and Andal had this bhava.”

With madhurya bhava comes viraha vedana, the agony of separation from the beloved. A recent PhD dissertation by Holly Hillgardner compares the expressions of viraha in the poetry of Mirabai and Hadewijch, a 13th-century Christian mystic: “Each woman’s respective longing for the divine not only takes her on an inward journey but also opens her up into an entangling involvement in the beauty and sufferings of the world.” Viraha bhakti transcends the poet’s internal sphere of consciousness and connects them to the external world. In this poem, Mira shares this feeling with a bird:

Hey, love bird, crying cuckoo,

Don’t make your crying coos,

For I who am crying, cut off from my love,

Will cut off your crying beak

And twist off your flying wings

And pour black salt in the wounds.

Hey, I am my love’s and my love’s mine.

How dare you cry love?

But if my love were restored today,

your love call would be a joy.

I would gild your crying beak with gold

and you would be my crown.

Hey, I’ll write my love a note,

crying crow, now take it away

and tell him that his separated love

can’t eat a single grain.

His servant Mira’s mind’s in a mess.

She wastes her time crying coos.

Come quick, my Lord,

the one who sees inside;

without you nothing remains.

Hawley and Juergensmeyer 2004

In her poem, Mira addresses not just any bird, but a cuckoo, a love bird. Like Mira who is cut off from her Krishna, the bird is a legendary symbol of anguish, said to be crying due to love’s separation. In this instance, viraha gives the lover agency. Mira threatens the bird that if it continues to cry, she would cut off its crying beak, twist off its flying wings and pour black salt in the wounds. These threats challenge the gentle demeanor that traditionally surrounds the figure of Mirabai, a royal princess, wife and devotee. If we transpose the image of the rebellious Mira who broke all family ties onto this poem, it starts making more sense. My translation of a line from Nabhadas’s Bhaktamal is as follows: “Unrestrained, totally fearless, she enjoyed singing the fame of her lord.” This unstrained image of Mirabai resonates with the harshness of the first stanza.

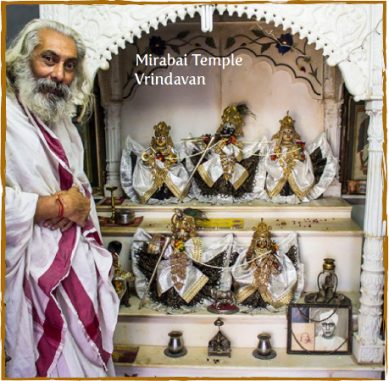

Precious legacy: Praduman Pratapsingh, priest of the Mirabai Temple in Vrindaban. Enshrined here holding two cymbals, Mira has been elevated to equal status with Radha.

The second stanza begins with strong possessiveness, a quality often found in the lovelorn gopika. “How dare you cry love?” she challenges. In the next line, her stance softens and she promises to reward the bird and cherish its love call if her own love is restored. The sudden change in temperament reveals the unstable mind of a virahini, unrestrained in love. Mira then asks the crow a favor: to deliver a note to her Lord. Crows are traditionally known to deliver messages. Mira urges the bird to tell her beloved that because of his distance she can’t eat a single grain. This speaks to the urgency of Mirabai’s love; she cannot stay apart forever and may starve to death. The bird serves as a lady friend (sakhi), confidant and messenger, which reflects Mira’s entanglement with nature. The body-mind connection is apparent: Mira “can’t eat a single grain,” as her “mind’s in a mess.” She then decides that all this cooing is a waste of time as her beloved makes her long in separation. The phrase “the one who sees inside” refers to the Hindi word antaryami, connoting that Krishna knows of Mira’s suffering, and places the onus on him to respond to her urgent coo. Mira finally pleads with her Beloved, “without you nothing remains.” Here is my translation of a Mira bhajan that I often sing.

Manmohan Kanha Vinati

Mind-captivating Kanha, I make just one request:

All day and night

My eyes are constantly watching the path.

Give me your darshan right now,

O Kunjbihari,

My mind is restless and impatient!

The thread of love binds us together.

This bond cannot be broken.

Hey, flute-bearer Krishna Murari,

I don’t have any peace.

My eyes are constantly watching the path.

Give me your darshan right now,

O Kunjbihari,

My mind is restless and impatient!

This song can be considered on multiple levels: lover to beloved, devotee (bhakta) to God (Bhagavan), and individual consciousness (soul; jivatma) to supreme consciousness (Paramatma). The poem would interest a person whether they are inclined towards the path of devotion (bhakti marga) or the path of knowledge (jnana marga). One who enjoys devotional literature reflects on their personal relationship with Lord Krishna, while someone who enjoys philosophy gets intellectually inspired by the jivatma-Paramatma dynamic.

Mira’s poetry also satiates the spiritual seeker who may not be of Indian origin or identify with Hinduism. Nancy Martin, scholar of devotional Hinduism and gender, describes in a 2010 article how Mirabai comes to the US: “Americans begin looking for figures for inspiration and canonization within an emerging non-institutionalized global spirituality and women around the world mine the past to find their spiritual foremothers.” Universalized metaphors of love and longing, union and separation, allow the poems to transcend time and space. Not only can the metaphors in Mirabai’s poetry be universalized, but her turbulent life story also carries the universal message of hope, courage and triumph in the face of adversity. This makes the historical Mira a powerful female character that serves as an inspiration for novelists, filmmakers, philosophers, social activists and feminists, says Martin. Thus, diverse people around the globe find cultural and spiritual relevance in Mira’s 500-year-old poems.

My Mirabai Expedition

By Mariellen Ward

IN OCTOBER OF 2014, I UNDERTOOK THE MIRABAI EXPEDITION, A cultural journey in the footsteps of Mirabai, a 16th-century poet and Krishna devotee, traveling to all of the primary sites in India associated with her amazing life. It was made possible by an Explorer’s Grant from Kensington Tours, as part of the Explorers-in-Residence program. Mirabai’s life has relevance today because her story parallels the struggle many women have attempting to live a fulfilled, creative life while society pressures them to settle down, marry and devote themselves to domestic obligations and duties.

My First Stop: The Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan

It is the first day of my journey and I’m a 54-year-old feeling very vulnerable. India can cut you open. The early morning taxi to Nizamuddin train station, leaving behind friends, leaving behind Delhi and festival time, leaving behind Ajay. Last night we walked in the park at dusk with the sounds of Ravanna burning, and bursting fireworks all around us. Trees filled with unseen birds making a roof of noise. Sikh taxi driver in a black van with yellow stripes, the kind of Delhi taxi I know so well. Then the first early morning India train in a long time. Very skinny people on the side of the road, wrapped in fabric, noisy chai stalls, shantis, broken pavement, a stream of litter, everything tinged in red sandstone and pink sunrise.

Arriving at the station, I’m greeted by a porter who demands way too much money, and I don’t have very much fight in me. He seems nicer than most, less hard, so I capitulate at an exorbitant Rs 150, two or three times what I should be paying. But he is going to wait with me for the train, find my car, my seat and put my bags on the rack. It’s convenient and frankly worth the money. The train arrives on time and I find my seat beside a large and assertive couple. I sense they would like to spread out and take all three seats and feel I have to fight for my space, as first her elbow, and then his (after they change seats) appears in front of my face.

I try to read my book about Mirabai but it’s hard to concentrate on the flowery language, full of descriptions about her devotional fervor. I don’t feel this kind of spiritual intensity, so it’s hard to imagine or grasp. Is belief an act of faith? Is it a feeling, like falling in love?

As I set out to trace her route, her journeys and try to get a sense of her life, I wonder how similar we are, and how different. I was born into a kind of freedom she could never have imagined as a woman in traditional India. But I cannot imagine her religious ardor, and her courage in striking out on her own to travel the dusty roads of this ancient land.

The train ride from Delhi to Mathura Junction is just two hours, and it arrives pretty much on time. I’m hungry, as I have only munched on some fruit, an Indian milk drink and some railway chai—which comes in a small cup with milk, sugar and tea bag for seven rupees. I forgot to pack my thermos.

The Taj Express stops in Mathura only for three minutes, and a large group has piled up their suitcases in the door. They notice my concern and make way for me to move to the next door. After I get down, I notice someone has been calling me on the phone, and before I can answer, a smiling young man says my name—actually a word that sounds enough like Mariellen for me to know it’s Pupendra, the person I am supposed to meet. He takes my bags and we walk a long distance down the train platform to the car park, where masses of green-and-yellow autorickshaws are waiting.

Pupendra tells me Vrindavan is “a special place, best place in India, most sacred city.” Then he hands me over to his friend, whose name sounds like Sagar, and whose auto is somewhat less smart than the others. Sagar is going to take me to Gopinath Bhavan in Vrindavan, where I’m staying.

It’s a long, hot, dusty, bumpy ride—first out of Mathura and then through a stretch of countryside and into Vrindavan, which does seem a bit different than your typical Indian town. We drive down narrow cobbled streets, and everything is dry and dusty and a kind of pale ochre color that reminds me of Italian Renaissance paintings.

Finally, the river Yamuna appears on our left and we drive along a narrow road with a line of intricately carved temples and ashrams on the right, facing the water. Some of the buildings are quite lovely, with cupolas and spires and carved facades. We stop at one of the loveliest, a large three-story building made of deep rose sandstone and carved in traditional haveli style. This is Gopinath Bhavan, a ladies ashram in Vrindavan that looks old but is actually quite new. Out front, cows are gathering to drink. I see monkeys above in the single tree, and a group of devotees walking barefoot.

Inside, the courtyard is cooler and rosy-hued. I am met by Tungavidya Dasi, whom I know only from Facebook, and she signs me in and shows me my room. I’m happy to meet her in person; she is a warm and sweet-faced Dutch woman in a pale sari with white hair. I’m on the top floor with a view of the river and Parikrama Road—the road the devotees walk along as they do their circle of the town.

After failing to buy an umbrella and finding only empty ATMs, I go back to the ashram with almonds, water and Limca. Happy to see my room cleaned, I promptly fall sound asleep, which seems like the sensible thing to do between 2 and 4 pm, when the sun is baking hot.

At 5 pm, the scene outside my window seems milder, the long slanting rays adding a picturesque quality to the Indian version of Canterbury Tales. It’s time for me to find the Mirabai Temple, so I grab my camera bag, make sure I am monkey proof and head out into the melee.

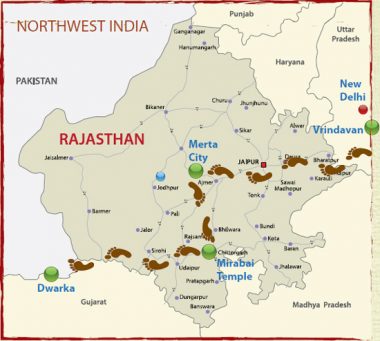

In Mira’s footsteps: A map of the author’s travels to the cities most central in Mira’s life. 1. The Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan, Uttar Pradesh; 2. Merta City, Rajasthan, Mirabai’s birthplace (Mirabai Temple & Museum); 3. The Chittogarh Fort with its Mirabai Palace and nearby Mirabai Temple; 4. Dwarka, Gujarat, the Dwarkadesh Krishna Temple in which Mira merged with Krishna.

After walking for about 15 minutes and asking many people, I find myself in a narrow, ancient street. A sewage drain runs down the side of the cobbled lane, brick shows through the crumbling ochre-tinged plaster, scalloped door frames surround heavy, wood doors, and again I am reminded of medieval Europe—except with monkeys and Eastern architecture. Finally, a small sign, and a door to an even narrower lane. Another false start, another tribe of menacing monkeys, and I find it. Through a rusty gate and I’m in a small, cool, serene, blue-and-white courtyard. Charming, fresh and modest, the Mirabai Temple is more like a home. A small group of Indian pilgrims sit in front of a grate where a white-bearded man is talking to them. They are all very engaged. Unfortunately, it’s Hindi and I understand only a fraction. However, the man also speaks English and agrees to repeat what he’s said.

He explains that his ancestor built this home for Mirabai five centuries ago, and she lived here in this spot for 15 years, before going to Dwarka. I am absolutely delighted to find such a charming spot and such an articulate, open and fascinating man. I can’t believe that I have been so lucky on the very first day of my pilgrimage expedition.

I take photos and a short video and realize I have not brought a notebook. I tell the man I will be back tomorrow to interview him and I leave at sunset. As I walk back along the busy road, I take a detour along the riverbank, avoiding the monkeys but putting myself in the way of the river boat touts. It’s worth it to take some stunning photos of the huge orange ball of the sun sinking into the river, and the colorful small boats gliding along the surface. A boy rides a huge black water buffalo across the river and as I take a video they suddenly emerge right in my path and I run.

Everywhere, there are animals and people in this dry landscape. A manic, naked holy man suddenly appears and runs down to the boats. He is wearing only a Brahmin’s thread. He doesn’t surprise me at all.

I pick my way carefully back to the ashram and dive into the quiet and safety of my room—which luckily, and surprisingly, has an A/C unit—to think about my day. I realize that I desperately need a sanctuary to be in India. I can only expose myself to the heat and the crowds and the challenges and the noise for so long. It’s hard on my nerves, and it’s emotionally draining.

In the bhakti tradition: The Mirabai Temple in Merta City, Rajasthan

During lunch at Govinda’s, I listened with bemusement to the Russian woman’s talk about Vrindavan, and the mythical lore of this place—where Krishna and his gopis cavorted on the river bank. The classical image of pastoral, lush and harmonious Vrindavan is so far removed from the dirty, polluted, over-crowded, dry, monkey-menaced, scorched-earth reality of today that it’s shocking.

I read that Mirabai was also shocked when she arrived in Vrindavan in the mid 16th century, because she didn’t expect any buildings. She, too, was expecting a pastoral paradise. Is this what faith is all about? That we hold up an ideal to hang onto in the face of the disappointments of reality?

Anyway, I’m here, and I’m lonely, and I don’t love Vrindavan, I don’t feel I have found a sanctuary, and I’m not sure what I’m doing here, except dedicating myself to the discipline of the pilgrimage, to stick with it and go through whatever ups-and-downs, emotional roller coasters and life lessons are in store for me. Perhaps this is my first glimpse into what it may have been like for Mirabai to leave the comfort and safety of home to follow her heart and the call of her soul.

Finding My Way in Vrindavan

I awake in Vrindavan with two problems on my mind: money and food. I slept without dinner, and no breakfast is available; and the day before, I tried two ATMs and both were out of money. So, with a mixture of hope and trepidation, I haggle for an auto and go straight to the ATM. The sound of the money dispensing is more delightful to me than all the temple bells in this moment. Even in a holy city like Vindravan, money is necessary.

From there I go directly to Govinda’s Restaurant at the ISKCON Temple for breakfast. As it is an “ekadasi day” (a day without grains), I have a strange breakfast of fruit, juice, a mango lassi and kind of potato dosa. Then I have their thick herbal tea and a coconut laddu. With money in my wallet and food in my tummy, I feel so much better about life and about the day. I hail a bicycle rickshaw outside ISKCON and fall into the usual negotiations over the price. They say 100 rupees, which is two or three times the price that Indians pay. A young woman joins in and bargains one driver down to 50 rupees to take me to the Mirabai temple.

We ride through a long, narrow market area. It’s fascinating to see the stores, the old buildings, some carved, and the crazy traffic jams. Bullock carts, a camel cart, every type of vehicle, all vying for space in a narrow street. We pass tiny children playing and open-air barbers and groups of devotees walking parikrama in their bare feet. Finally we get there. Because of the distance and the heat, and the man’s advancing age, I decide to give him 100 rupees after all. He isn’t sure whether I mean for him to keep it. I feel his sweetness and humility in my heart; I feel humbled.

Immediately on stepping through the old rusty gate and entering the small residential temple, I feel cooler and calmer. I love the feeling in this shady, airy house, full of light and greenery, painted pale blue and white. The bearded man appears, this time in a more priestly garb, a white robe trimmed in red, and we sit down to talk. He gives me a piece of paper with information about Mirabai, tells me it’s at least 45 years old, and that I should have it translated and copied. On it he has carefully printed his name and address: Praduman Pratapsingh, Mirabai Temple, Govind Bagh, Vrindaban. Praduman tells me, in simple English, what’s written on the paper, which is in Hindi. He goes through the main details of Mirabai’s life, and how she was rejected by her husband’s family because of her devotion to Krishna, her dancing and singing. This is why she came to Vrindavan—to find peace and devote her life to Krishna.

Praduman’s ancestor built this temple for her to live in, and she lived here for about 15 years. Apparently she wrote many poems here. He continues to tell me her life story. Mirabai went from Vrindavan to Dwarka. While she was living in Dwarka, when she was about my age (around 50), there was a drought in Rajasthan. Some of her family members traveled to Dwarka to entreat her to return, but she refused. That night, according to Praduman, she dissolved in Lord Krishna—and the drought ended.

Praduman talks about Mirabai with conviction and enthusiasm, and though he must do this several times every day, he seems passionate. He has an open face, large eyes, and is very expressive. He shows me around the temple, poses for me and even opens the altar grate so I can photograph the statues. He tells me he is the ninth generation of his family to be born here, and to maintain the temple. He has a son and daughter—they are the 10th generation (but his son is an artist and animator in Mumbai).

“People come here for peace, love and spiritual strength,” Praduman says. “This is the real place of Mirabai. She lives in this temple. People who come here can feel Mirabai and Gopal (Krishna) in their hearts.” Though I am not a Krishna devotee, I do feel a light, happy atmosphere in this temple.

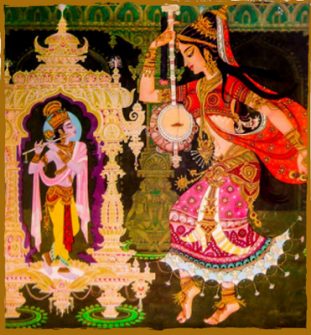

Otherworldly: Mirabai dances and plays music with Krishna in a Rajasthani-style painting

Onward to Rajasthan

I wake up on the third day feeling satisfied. Meeting Praduman and basking in the delightful energy of the Mirabai Temple is such a great start. Vrindavan in myth and legend is a fecund place of peace and harmony, a kind of Garden of Eden where Krishna and his gopis (milk maids) cavorted in innocence, bathed in love. Vrindavan in reality cannot be further from this image. It must take enormous faith for the many devotees who flock here to feel the spiritual energy of this place. I feel a bit bad about not feeling Krishna’s energy here. But when I was discussing the Mirabai expedition with a woman I met at Gopinath Bhavan, she said it’s great that I am giving attention to one of the female players in the Krishna story. So be it. I am happy to move on.

I have to be in Agra to take the train to Rajasthan at 5pm, so I make plans for a taxi to drive me there in the late morning. I consider seeing the Taj Mahal (for the third time), and decide to stop at the ITC Mughal hotel, taking me on an unplanned detour into luxury, and it feels right. Mirabai was a princess who lived in a sumptuous palace before striking out on her own, both to escape the cruelty of her husband’s family and to follow the voice of her soul, the call of her devotion to Krishna. There is synchronicity in this visit, too, as the ITC Mughal celebrates the era of Emperor Akbar—who visited Mirabai in disguise and praised her talent and devotion, bestowing upon her a valuable necklace.

So, as Mirabai left her palace home, I have to leave the comfort of the ITC Mughal to brave the chaos of the Agra train station.

A Broken Heart, a Spiritual Journey

The train is late, but eventually it arrives, I find my berth and settle in for the journey to Ajmer in Rajasthan. I’m in a lower berth in the second-class compartment. Somehow I like taking the train in India. I like the gentle movement and knowing I am going somewhere fascinating—plus I like it better than driving. The roads in India are a chaotic obstacle course and you really do feel you are taking your life in your hands. The movement of the train makes me philosophical. In Pushkar, Avtaar meets me and we walk together through town to meet someone that Anoop, owner of Inn Seventh Heaven, suggests I talk to about Mirabai. So we walk out of the haveli, around the corner and we are in the busy market that wraps around most of the lake. We go straight to meet Ravi, of Roots of Pushkar music store. Luckily he’s there and happy to chat.

The amazing Chittorgarh Fort, stronghold of the proud Rajput rulers, whose exploits are the stuff of legend

As a music lover, Ravi knows Mirabai primarily through the songs and bhajans she wrote, or that were written about her. He brings out three CDs, two beautifully produced (by Roots of Pushkar) with great cover art and booklets, and I buy them all. Then he calls his brother-in-law Milap, in Merta City, and arranges for me to have a tour of the Mirabai temple the next day.

I have come to expect this kind of over-the-top helpfulness in India, but I hope I never take it for granted. India can be challenging and frustrating in so many ways, but the people usually make up for it. I have never met more warm and helpful people anywhere.

Finding Mirabai in Merta City

Avtaar and I meet the next day for our drive to Mirabai’s birthplace. I’m really excited to explore the second stop on the Mirabai Expedition, and the unknown journey that awaits. We drive out of Pushkar and past the vast desert-like fields that host the annual Pushkar Camel Fair. Within an hour we are in Merta City and look to meet our guide.

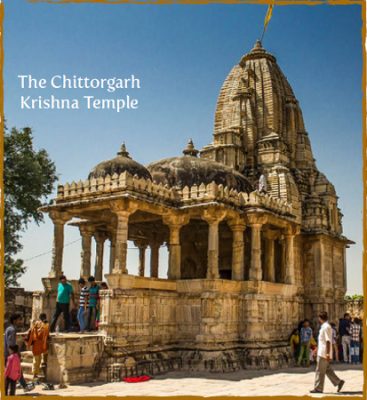

In Rajasthan: The Mirabai Krishna Temple in Chittorgarh, built for Mira by her father-in-law, who was initially pleased with her devotion

We park in a narrow lane beside a temple and find Milap and his young son waiting for us. They escort us upstairs to their home, a spotlessly clean, light-filled, spacious flat over an electronics store. We meet his wife and daughter, too, and enjoy chai together.

Milap, his son and his daughter accompany Avtaar and me to the Mirabai Temple. I started as one, and now I am part of a five-person entourage. After walking for about 10 minutes along a narrow road through a busy market in the hot sun, suddenly, in the midst of all the bustle, we are at the Mirabai Temple.

I am immediately impressed with the place—by the size, the design, the beauty of the temple The atmosphere inside is tinged with green light because of the green plastic roof. A serene statue of Mirabai faces across a checkered tile courtyard towards the inner sanctum, the Krishna Temple. She is frozen in an adoring gaze of love and devotion.

A group of women sit in the courtyard playing music and singing Mirabai songs. After darshan in the Krishna Temple, I join them on the floor to experience the camaraderie of women and the music of Mirabai. It’s a wonderful and exhilarating experience. I feel warmly welcomed by them. One woman hands me a pair of cymbals while others move aside to make room for me. The woman leading the singing catches my eye and signals for me to join in.

I am beginning to get an idea of Mirabai—the joy and love she engendered, and the femininity of her creativity and devotion. And I am delighted to see that she is still honored today in her birthplace, in a very real and kinesthetic sense.

Leaving the temple, I feel full, satisfied with my Mirabai experience. But much to my surprise, Milap tells me we are going to the Mirabai Museum next door. This is news to me. I had no idea. The Mirabai Museum never came up in my research.

Striking Gold at the Mirabai Museum

I discover it’s a fairly new museum in a very old building, housed in the former palace that was her home. I am dumbstruck, because I thought her house was in ruins. It turns out the house she was born in is in ruins, but the red sandstone building I am entering is where she grew up.

Women gather to sing Mira songs inside the Mirabai Temple in Merta City

We enter through a thick, medieval-looking gate into a sizable courtyard. At the back of the courtyard is the palace. It is not big, but it is impressive enough. Most impressive is the care and thought that went into preserving the name of Mirabai here. Her life is plotted with signboards, portraits and paintings throughout the lofty rooms. In the main room (perhaps the throne room?), there is a beautiful gold-colored life-size statue of Mirabai behind a railing in front of a portrait of Krishna.

I am really impressed with this display; it evokes the quality of devotion and reverence that Mirabai represents. As I’m standing at the barrier, paying homage to Mirabai and also trying to imagine her actually living within these rooms, I am introduced to two local journalists. It seems like a coincidence they are at the museum at the same time as me.

I continue to walk slowly, enjoying the spacious rooms, naturally cool even in the heat of the day, and filled with delightful images of feminine beauty and heartfelt devotion. My entourage continues to grow as I walk, with the journalists and several young local people joining us.

As I walk out through the massive, medieval museum gate into the glare of the noonday sun, I remember the story about how Mirabai stood in this same spot with her mother and watched a passing marriage procession. “Where is my groom? Whom will I marry?” she innocently asked her mother, who pointed to an image of Krishna and said, “Krishna is your groom.” This idea stuck with Mirabai for the rest of her life. Milap’s 10-year-old daughter and I take pictures of each other posing as “strong women,” with our hands on our hips, and I hope she takes the attitude with her for the rest of her life.

Chittorgarh Fort: in the Footsteps of Royalty

Rajasthan is literally “the land of kings,” a desert state with a rich history of chivalrous rulers, silk-road trade routes and romantic tales. Fantastical palaces and sand-castle forts, loping camels and screeching peacocks, women in neon-bright saris and men in bulbous turbans. Rajasthan is all your fantasies of India writ large, and the setting for many of India’s epic stories, including the improbable tale of Mirabai.

Mirabai was born a Rajput princess in Rajasthan around 1500. Her father, Ratan Singh, was the second son of Rao Duda ji, a descendent of Rao Jodha ji Rathor, the founder of Jodhpur. She was a renowned beauty known for her sweet voice and devotional nature, and was sought in marriage by a powerful Rajput family. She married Bhojraj, the son of Rana Sangram Singh of the Sisodia Dynasty, the powerful King of Mewar and ruler of the Chittorgarh kingdom.

Mirabai’s Royal Connections

I read that after marrying Prince Bhojraj, Mirabai moved to Chittorgarh to live with her husband’s family, as all Indian brides did, and most still do. But now I’m in Chittorgarh Fort, near Udaipur, and seeing the remains of the fort, the crumbling palaces and well-maintained temples, her story is becoming real. It’s becoming real because I am walking where she walked and prayed; it’s becoming real because I can see for myself the prestige and power of her husband’s family.

As Avtaar and I drive into a Chittorgarh on this hot, sunny day, I’m struck by the vast size of the fort, which covers the mountain plateau, and how it towers over the modern town below. We head straight for the Castle Bijaipur hotel, about 25 kilometres outside of town, by far the top hotel in the vicinity; and it’s well worth the drive.

Partially still occupied by the royal family, Castle Bijaipur is the most evocative heritage hotel I’ve ever stayed in. They managed to modernize the rooms without losing the original character, and wisely left the patina of age. I feel like a princess in my large room with private balcony overlooking the town below, with its warren of medieval streets.

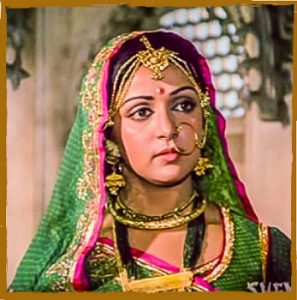

Remembering Krishna’s devotee: A scene from the 1979 film, Meera

Arabian Nights’ Castle in Rajasthan

At dusk I walk the grounds of the hotel, going up onto the roof to take photos from among the turrets. I sit on a cushioned window seat overlooking the inner courtyard, and also try out a swing seat. Before sunrise I walk through the quiet empty grounds to the massive gate to await my friend Ajay, who’s arriving by train from Delhi. I feel lost in time, as if I’ve stepped into the pages of the Arabian Nights. In the morning I’m awakened by devotional music coming from a nearby Hindu temple, and the call to prayer from an equally nearby mosque.

Castle Bijaipur has put me into exactly the right frame of mind to spend the day in Chittorgarh Fort. It’s a hot day, but we set out early and drive directly to the fort, engaging a guide at the entrance who travels with us. Far too big to walk—the circumference of the walls is 16 kilometres—we drive from place to place. Our first stop is the 15th-century Kumbha Palace, a vast site of crumbling walls and clambering monkeys. While the guide wants to give us every word of his memorized spiel, I entreat him to just show me the Mirabai Palace. To my surprise he takes me directly there, to a small building in the corner, with a sweeping vista. Though it is in ruins, the effect is still very much as if we’re in a palace in the clouds. I’m absolutely charmed.

Mirabai Escapes Three Attempts on Her Life

Our next stop is the Mirabai Temple, built for her by her father-in-law, the King of Mewar, who was initially pleased with her religious devotion. It is, of course, a Krishna temple, a small, intricately carved building on the grounds of a much larger Vishnu Temple. The temple is a well-maintained, sacred pilgrimage destination. A woman sits in the entrance singing Mirabai songs, and inside I see a beautiful white statue of Mirabai in front of the Krishna murti.

It’s a delightful temple and I’m thrilled to be here; however, I am very surprised to see a stall set up inside selling books and souvenirs. A signboard inside reads: “Meera Temple. This is the temple where Mira worshiped Lord Girdhar Gopal—chanted hymns and danced. Here is the place where poison was turned to nectar.”

Mirabai’s in-laws did not accept her ecstatic devotion, feeling that her behavior was not seemly for a Rajput princess. After her husband died, and word got out that Muslim Emperor Akbar—the sworn enemy of the proud and independent Hindu Rajputs of Chittorgarh—had visited her in disguise, they attempted to kill her. Three times they tried, and three times she was miraculously saved.

The first time, she was given a basket of flowers with a poisonous snake hidden inside. The second time, she was given a cup of poison to drink. The third time, she was asked to drown herself. Lord Krishna was credited with the divine interventions that saved her, by turning the snake to a stone, the poison to nectar, and by lifting her out of the water. According to the sign, the third attempt on her life happened at this temple. It was after these incidents that Mirabai left her royal home forever, to wander as a sadhvi in North India.

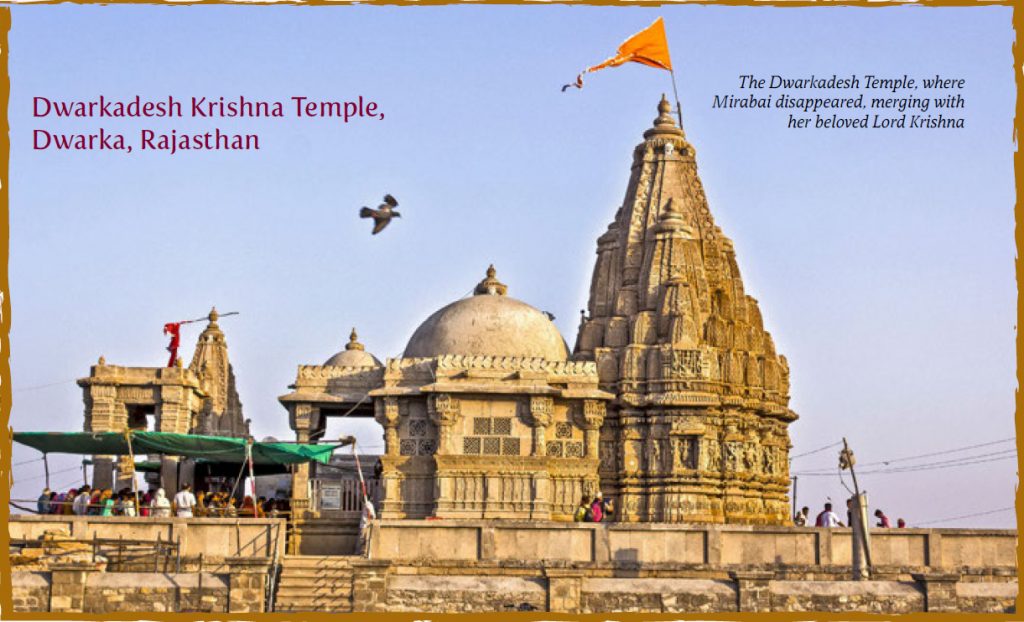

Dwarka: Releasing the Bonds of Love

Crossing the desert, we reach the remote seaside town of Dwarka. This is where Mirabai’s story ends, where she mysteriously disappeared in front of crowds of people while singing in the temple to her beloved Krishna, when she was about my age. And this is where I wonder how my own story will end.

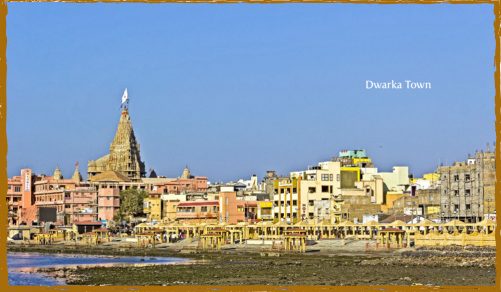

Dwarka is a flat place, barren, washed by sun and sea. But the light here has a crystal clarity, and the colors are few: beige sand, blue sky, silver sea. I feel calm here, and obviously Indians do, too, because the frenetic pace of most Indian towns is almost non-existent here.

Though a small town, Dwarka is awash in temples, new and old, grand and modest. The 5,000-year-old Dwarkadesh Temple in the center of town towers over all of them. Everything revolves around this temple, which emanates an ancient feeling and evokes deep reverence. Otherwise, Dwarka is a modest place of narrow, winding, colorless streets and the usual conglomeration of shops, stalls, cows, sadhus, beggars, cyclists, two-wheelers, autorickshaws and the like. But the pace is slower and the sea air gives it a special quality.

The sacred town of Dwarka, on the embankment of the Gomati River, with white flag atop the Dwarkadesh Temple

Miracles Begin to Happen

I like Dwarka instantly, though it is far from beautiful. My hotel faces the sea; otherwise it has nothing special to recommend it; a characterless box with awkward young men working behind the desk and in the restaurant. The sea front here is lined with concrete, dotted with temples and smattered by cow dung. It is not what a Westerner would call picturesque. It was just down this coast, in Porbandar, about 43 miles away, that Mahatma Gandhi was born.

After checking in, the first thing I do is ask one of the young men behind the counter if there is a local guide who can help me learn about the temple. He says there is one priest who speaks English and he will call him. I go back to my room with my expectations in check. After five minutes, I get a call from the front desk. The priest has arrived. The first miracle.

To say I am surprised to find a handsome, charismatic young man in a crisp, clean silk dhoti, who speaks almost perfect English, waiting for me is a gross understatement. If I had planned ahead, I would never have met a better guide than Hardik Dwarka. Not only does he speak English, he has a sophisticated understanding of the world and he is from the Googly Brahmin caste that has served the Dwarkadesh Temple for hundreds of years. I immediately sense that Hardik is a special person, and my short association with him proves this to be true. Hardik and I arrange to meet at 5pm, when the temple reopens, and he is right on time. The second miracle.

Meeting Mirabai at the End of Her Story

My driver, Gopa, drives Hardik and me first to the Mirabai Temple in the center of Dwarka. It is a modest temple in the market area, and you would never find it without a guide. Hardik tells me it is quite new, and built by Sadhri Devi and her followers from Nagor, Rajasthan. While I am pleased to find the Mirabai Temple, I don’t get any particular feeling from being there. Mostly, I am pleased to see women celebrated—Sadhri Devi also seems to be a musician.

From there we drive through the dusty streets to Dwarkadesh Temple, as Hardik explains that Krishna lived for 100 years in Dwarka. He came here for the quiet, and there is still a sense of quietness about this sacred town. Krishna built Dwarkadesh Temple 5,000 years ago. Dwar means “gate or entrance,” and ka indicates “moksha.”

Gopal drops us outside the temple compound where people are gathering. Beggars line the outside wall, flower and tulsi sellers walk around with garlands, hawking their wares, and large groups of pilgrims arrive with anxious excitement. We walk slowly through the crowd, and as Hardik speaks, I become aware only of his presence and his words. He completely holds my attention, even in the madding crowd.

“Krishna is awareness,” Hardik says, “He teaches us that the past and future is not real. Only now is real.” For the first time, I feel like I have found a way to understand Krishna. Maybe someone said this to me before, but at the Dwarkadesh Temple, I finally heard. All the many years I studied and practiced Gestalt and then yoga, I was also trying to understand this teaching. Hardik makes Krishna accessible and real to me. I ask him about Mirabai. “Mirabai shows us a different way to love. In her love for Krishna, she didn’t want anything. In reality, lovers are always givers and takers. Mirabai’s love for Krishna was amazing. There were no boundaries; she forgot herself. The saints told her that her love was very powerful.” Krishna is awareness and Mirabai is love.

We drop our shoes and my camera at a counter and enter the temple. I immediately feel I am surrounded by ancient, sacred energy and know this is a special place. The spire of the temple towers above us, covered in ornate carvings, topped by a bright silk flag fluttering in the sea breeze. Hardik takes me directly to the heart of the temple, the inner sanctum, to see the black figure of Krishna, bedecked in colorful garments, deeply set in a recess and surrounded by several frames of gold and silver. Two queues of anxious people, male and female, corralled by metal gates, are pressing against the barrier for darshan, to see the figure of Krishna.

I find the darshan a bit overwhelming and am happy to move out of the main temple and walk around the compound. As we talk about Krishna, Mirabai, Hinduism, spirituality, religion and our own lives, we make our way around the temple and to the back of the darshan lineup. On a raised marble platform in front of the temple dedicated to Krishna’s mother, I can see above the pilgrim’s heads into the inner sanctum. I am completely surrounded by the womb of the temple and stand happily, imbibing a feeling of calm, and imagining Mirabai singing her love for Lord Krishna on this very spot. Here was the place she disappeared.

I ask Hardik about the disappearance, and he says that only a small square of her sari was left and that it was placed on the Krishna statue. In my research, I learned she was drawn to Dwarka by the extreme sanctity of the Krishna Temple, and she was perhaps running a soup kitchen for the poor at the time of her disappearance. The spiritual tradition is that she dissolved into love for Krishna. But others, less mystically inclined, say she fled from her fame. Apparently, a delegation was sent to Dwarka to persuade Mirabai to return to Chittorgarh because of either a political situation or drought. By this time, she was about 50 and famed for her ardent devotion and beautiful poems and songs. She may not have wanted to return to Chittorgarh, for obvious reasons—her in-laws had tried to kill her. Perhaps she decided to leave her identity behind and run away. Or perhaps she did undergo a spiritual miracle.

The Key to the Mirabai Story

It’s my second morning in Dwarka. I meet Hardik again, at 6:30am, and we go back to the temple. We go into the temple compound where I join the queue for darshan. A woman in a mauve sari pushes me several times, though I motion for her to stay calm, to wait her turn. She pushes again and I say in English, knowing she will not understand, “Where do you think God is? You think God is only up there?” She ignores me, but the woman behind her understands, and makes room for me. So I let the pushy woman go ahead, and then enjoy the space created by the understanding woman, recognizing that I am experiencing the flow of consciousness.

Afterwards, I go back to the spot at the back of the queue, on the raised dais, and stand again feeling the subtle energy. I feel a kind of buoyant joy undulating through me, from where my bare feet touch the smooth, cool marble floor all the way up through my body to the top of my head. It is a pleasant feeling, like bobbing on a summer lake.

Walking to where Gopal is waiting by the car, an old, bent woman in colorless rags holds out a cup towards me, begging for money. This happens all the time in India, and I have learned to harden myself against it. But this time, my heart is open and I want to give her something. I have no money with me, but Hardik gives me a small bill and I hand it to her. Our eyes meet and hers are filled with love.

I am stopped in my tracks. I feel overcome with emotion, and start to cry. Hardik asks me if I am okay. “I saw my mother’s eyes in hers,” I blurt out.

I can barely move. Waves of love, longing and grief wash over me. I lost my mother 16 years ago, and all the pain, and all the love, come rushing back. I have to stop and lean against a wall, letting the masses of cows and pilgrims pass in a blur. An eternity of time opens up. I am in distant Dwarka and I am at home in Canada. I am here and now and with my mother in the distant past.

And then, all of a sudden, I have the key to the Mirabai story, and the mystery of what happened to her doesn’t matter to me anymore.

I know what Mirabai’s essence was, what the key to her story is, and what I am meant to learn from this expedition. And I can say it in one word. Love. Love is all that matters. Krishna is awareness and Mirabai is love, and together they merged. This is our higher self. This is the story of Mirabai.

ABOUT MARIELLEN WARD

Mariellen Ward is an award-winning professional travel writer based in Toronto and Delhi. Inspired by her extensive adventures in India, she launched a travel service, Breathedreamgo, in August, 2009. Her passion, exploring India, is the theme underlying all of her “meaningful adventure travel” writing. Canadian by birth, she considers India to be her muse and her “soul culture.”

Enjoy Mariellen’s blog at breathedreamgo.com

Four of Mira’s Songs

THE FOLLOWING ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS COMPRISE COMMONLY sung Mira bhajans as well as texts of her poetry. The first three songs were translated by Nancy Martin in 2007. The fourth is Lakshmi’s work.

Mhārā re giridhar gopāl

Mine is the mountain-lifting Gopal, there is no other.

There is no other, O Sadhus,

though I have searched the three worlds.

Mine is the mountain-bearing Gopal, there is no other.

Brother, friend, relative, kin—all I left behind.

Sitting in the company of sadhus,

I abandoned the world’s expectations.

Mine is the mountain-bearing Cowherd, there is no other.

Watching devotees, I was delighted;

looking at the world, I wept.

The vine of love grew, watered by the river of my tears.

Mine is the mountain-bearing Gopal, there is no other.

Churning the milk, I extracted the ghee

and discarded the buttermilk.

Drinking the poison the rana sent, I attained bliss.

Mine is the mountain-bearing Cowherd, there is no other.

Mira has bound herself to love;

what was to be has come to pass.

Mine is the mountain-bearing

Gopal, there is no other.

Make me your servant, dear Mountain Bearer

Your servant, I’ll plant a garden.

Arising each day, I’ll come before you.

In the groves and lanes of Vrindavan,

I’ll sing of your love play, Govind.

Let me serve you, dear Mountain Bearer.

In serving you, our eyes will meet.

Remembrance will be my wages.

The land-grant of loving devotion my payment—

Desire of birth after birth.

Make me your servant, dear Mountain Bearer.

Peacock-feather crown,

yellow silk at your waist,

jeweled garland adorning your chest.

Enchanting flute player, Vrindavan’s grazer of cows,

Let me serve you, dear Mountain Bearer.

O Lord, I’ll plant new groves

with fragrant gardens beneath them.

Dressed in a red sari,

I’ll come to meet my Dark Love.

Make me your servant, dear Mountain Bearer.

At midnight, Lord, reveal yourself,

on Yamuna’s shore!

Mira’s Lord is the gallant Mountain Bearer—

A terrible restlessness fills her heart.

Let me serve you, dear Mountain Bearer.

Come, Lord Kanha. I have enchanted the Renouncer!

Come, friends, come and see Lord Kanha.

I have enchanted the Renouncer!

In a brand new pot, I’ve churned curds;

Come as a milk-seller to taste them.

In the green garden, I’ve gathered beautiful flowers;

Come as a gardener’s wife to enjoy them.

I’ve made a spinning wheel of sandalwood;

Come as a carpenter’s wife to admire it.

A needle of gold and silk thread I have;

Come as a tailor’s wife and take them.

Mira says, I sing of the Mountain Bearer;

Come and meet my guru Ravidas.

Pyāre darshan dījo āye

Come my beloved, allow me to see you.

Without you, I cannot exist.

Lotus without water; night sky without moon

is the state of a lover without seeing you.

Restlessly I roam day and night,

separation eating my heart out.

No hunger in the day, no sleep at night,

Tongue-tied with grief, no words.

What shall I say? I am unable to speak.

Now come, extinguish my pain.

Why make me thirst for you, knower of my inner self?

Come meet me by way of

compassion, O Lord

Mira, servant-devotee of many lifetimes,

forever remains at your feet.

Popular Mira Bhajans

Kenu Sang Khelu Holi by Lata Mangeshkar

Mharo Pranam by Kishori Amonkar

Aisi Lagi Lagan by Anup Jalota

Mat Ja Jogi by Anuradha Paudwal

Mira’s Music & Spirit Live On

MUSIC IS AN INTEGRAL PART OF UNDERSTANDING A POET-SAINT’s message, because it physicalizes his or her emotions in a tangible, “heard” way. Singing makes the emotions in Mira’s poems more accessible and immortalizes her poetry in the Indian devotional space.

Mira bhajans are popular in many Indian music genres, including classical, folk and devotional. Certain famous vocalists are known for their beautiful, heartfelt renderings of Mira bhajans, including Bharat Ratna recipients Lata Mangeshkar and M.S. Subbulakshmi. In North Indian (Hindustani) classical programs, singers often complete their concert with semi-classical devotional music. This usually consists of poetry by Mira, Kabir and other popular poet-saints. Folk artists who sing Mira bhajans include the Manganiyar and Langa communities, who are hereditary Muslim musicians in the desert regions of Rajasthan bordering Pakistan. They sing a rich repertoire of Hindu and Sufi spiritual music which includes Mirabai’s poetry. These highly skilled artists, who usually have Muslim or Hindu patrons, play traditional instruments that are specific to those communities. Musicians specializing in sacred music, either professionally or as a hobby, typically include Mira bhajans in their repertoire as well. Along with Kabir, Tulsidas and Surdas, Mirabai is among the most loved of the Hindi poet-saints, and, being the only woman in this pantheon, is one that female vocalists often choose to sing about.

Mirabai’s legacy continues not only through music, but also through historical temples. The Mirabai temple in Vrindavan, constructed by the minister of Bikaner state in the mid-nineteenth century, revolves around the story of Mira drinking and remaining unaffected by the cup of poison sent by her in-laws. Legend has it that they sent not only a cup of poison, but also a live snake that transformed into a black shaligram stone, a symbol of God universally worshiped by Vaishnava devotees. Hence the temple is popularly known as the Shaligram Temple. The arrangement of Deities at the temple corresponds to Nabhadas’ conception of Mira as a “latter-day gopi.” Krishna is in the center, with Radha on His left and Mira on His right. The symmetry suggests that Mira’s status is elevated to that of Krishna’s most beloved gopi, Radha. This temple is not only known for its historical significance as the temple Mira visited, but is an abode for current-day Mirabais.

In her article “Mirabai: Inscribed in Text, Embodied in Life,” Dr. Martin describes two modern-day women who identify with Mira. The first, a young woman living at the Shaligram Temple, regards herself as a Mirabai, devoting her life to Krishna. With a well-respected public persona, she sometimes dresses in sparkling golden clothes as Krishna, and other times in the saffron of a renunciate. Another, older, woman, called Lakshmi Bai but commonly known as Mira Mataji, also lives a life of service and devotion to Krishna in Vrindavan. Despite being a householder earlier in life, she lives today as a saint with a following of devotees, whom she treats as equals. She, too, is a composer, and her hymnal of three hundred and five compositions, called Sri Radha Krishna Bhajanavali, is used at daily satsangs.

Mirabai in Modern Media

WE CAN UNDERSTAND HOW THE LIFE AND IMAGE OF Mirabai has been adapted by studying South Asian popular culture. For instance, we can see how Indian cinema has constructed her story at different points in time, with corresponding regional and linguistic sensibilities. The shifts in social circumstances change the methods of transmission and target audiences, and the type of media affects the way certain stories are told. For example, in films and comic books, the visual is highly relevant. While traditional hagiographers didn’t need to ponder how to illustrate Mirabai, directors and authors must. Moreover, let us consider the different audiences that print comics and movies reach. Mira is portrayed as an ideal Hindu wife in the postcolonial illustrated comic series Amar Chitra Katha. The story stresses her dharma, followed by her bhakti. The comics served as “culture-makers” intended for a young Indian audience, while the films portray a strong and graceful Mira that women could relate to. The primary focus of both genres is the story of Mirabai and her bhakti and dharma, rather than her poems. These depictions play with the idea of radical bhakti as demonstrated by a female poet whose love of God supercedes the duties she shirks as daughter and wife.

Mira Films

Two popular films are available on YouTube, both portraying Mirabai as the paradigmatic Hindu female saint who maintains her devotion despite life-threatening obstacles, thus raising issues about bhakti, gender and a woman’s traditional dharma. The first is a 1945 Tamil movie produced in South India, and the second is a 1979 Hindi movie filmed in Mumbai. Both are stories of a devotee’s triumph. The latter film can be read as a nationalist discourse depicting a woman’s victory over power and patriarchy.

“Meera,” the Tamil language film directed by American filmmaker Ellis R. Dungan, features the renowned Carnatic vocalist M. S. Subbulakshmi. The decision to have an American director on a project that carried religious and cultural ideas is surprising. Dungan had moved to India only in 1935 and knew little Tamil. But his innovative videography and the prominence he gave to female characters in his previous work may have influenced this decision. The film was unique in that it starred a professional musician rather than an actress, and M.S. Subbulakshmi chose Mira’s role precisely because it carried a universal message of devotion. Her husband Sadasivam, seeking to advance his wife’s career, produced the film, replete with songs in Tamil rendered by M.S. Subbulakshmi. A few semi-classical songs in Sanskrit find a place in the film. Amazingly, none of the songs featured in the Tamil film are taken from the collection of Hindi poems popularly attributed to Mirabai; instead, they were specifically composed for the film by Tamil lyricists Papanasam Sivan and Kalki. Many of the compositions contain the word giridhari or the phrase mira prabhu giridhara gopala.

In terms of narrative, the film begins with a happy-go-lucky Mira who sings and dances with her friends. Mira is the granddaughter of Dudha Rao, a Rajasthani ruler. One day a swami (whom we later learn is poet-saint Rupa Goswami, a follower of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu) visits and brings with him a murti of Lord Krishna in the form of Giridhari. Little Mira is enraptured and imagines herself to be Radha. The film presents a scene with the young Mira as Radha dancing with Krishna in Vrindavan. Mira’s mother encourages her divine love, and the goswami, moved by Mira’s devotion, leaves his Giridhari murti with her. By age ten, Mira has lost both parents. Just a few years later, around 1516, at the insistence of her grandfather, she marries Kumbhaji Rana, the king of Mewar, despite her belief that she was already married to Giridhari. King Rana is portrayed as a devoted husband, encouraging Mira in her devotion to Krishna, building a temple at her behest, but ultimately regretting having allowed Mira to leave his kingdom. This is similar to Priyadas’ portrayal of Mira’s husband in his early 18th-century text Bhaktirasabodhini. In Gulzar’s 1979 Meerabai film, too, Bhoj Raj Singh is a devoted husband, exemplifying bhakti in the form of unconditional love for his wife. Mira’s devotedness, on the other hand, is focused entirely on Giridhari. Despite her best intentions, Mira is emotionally unable to live as queen and wife to Rana. In the Tamil film, Mira’s brother-in-law Vikraman tries to poison her via Rana’s sister Udha, but Mira is unaffected by the drink, a miracle that inspires Udha to becomes a devotee of the Lord. This is a famous story found in many Mira poems and legends.

Another prominent incident in the Tamil film is that Mira starts living in the temple that Rana built for Lord Krishna, singing with people of all castes including peasants and laborers, which the king disapproves of. This is also mentioned in Priyadas’ Bhaktirasabodhini. Rana’s frustration increases when he learns of a necklace that the Mughal emperor Akbar sends for Mira out of respect for her devotion and singing. A turning point in the film is when Mira leaves the palace, informing her husband that she doesn’t belong in the kingdom but in Vrindavan and Dwarka, where Lord Krishna lives. We see the transformation of Mira’s physical appearance when she leaves the kingdom, from a queen in royal finery to a devotee in a simple sari, no jewelry and with a vina in hand. She wanders on foot and finally reaches Rupa Goswami’s ashram in Vrindavan. Then they travel to Dwarka together, where she merges with Giridhari. In the film we see Mirabai’s physical body fall, but her soul is shown leaving her body and entering the murti of Giridhari. Rana arrives in Dwarka at the same time that this happens, and he too becomes a devotee of Krishna.

Gulzar’s Meera is different from Dungan’s. Most notably, there is an interpretation of Indian history running throughout the movie. Gulzar’s Krishna is the heroic Krishna from the Mahabharata, while in the Tamil version, M.S. Subbulakshmi is soaked in devotional love for the youthful, intimate Krishna called Giridhari. Gulzar’s social and political agenda may be deliberate. As scholar Heidi Pauwels states in her article “Who Is Afraid of Mirabai? Gulzar’s Antidote for Mira’s Poison,” “He [Gulzar] is aware that his interpretation is not “the truth” but a creative adaptation of the story as passed on to him” in order to make the film look real as well as adhere to Bollywood standards. The film begins with a conversation between Mira’s father and brother about the current political landscape. This sets the tone for the rest of the film, which heavily relies on the relationships between the various rulers. Mira’s character is introduced a few minutes into the film, where she is shown singing the popular Mira bhajan “Mere to Giridhar Gopal”. Her devotion to Krishna is apparent, though not the focus of the film yet. Mira has a cousin sister named Krishna in the movie, a character that we do not come across in historical or bhakti sources. As for Mira’s brother Jaimal, however, he is mentioned in hagiographies and political documents as Mira’s cousin brother. However, while in the movie he demonstrates enmity towards the Sisodiyas (Mira’s in-laws), Heidi Pauwels points out in her work that there is historical evidence to suggest that Jaimal “found a protector in the Sisodiya Rana Udai Singh of Mewar.”

ABOUT LAKSHMI C. SUBRAMANIAN

Lakshmi is a California based vocalist-scholar who brings devotional music and scholarship onto one platform. She holds an M.A. in Religious Studies from Stanford University, and writes on the great Indian vernacular poet-saints. Originally from Singapore, she has several devotional album credits with her mother and guru Padmini Chandrashekar. Lakshmi performs shows of contemporary devotional music with her husband Aks under their company Eclipse Nirvana (www.eclipse-nirvana.com).