By M.P. MOHANTY

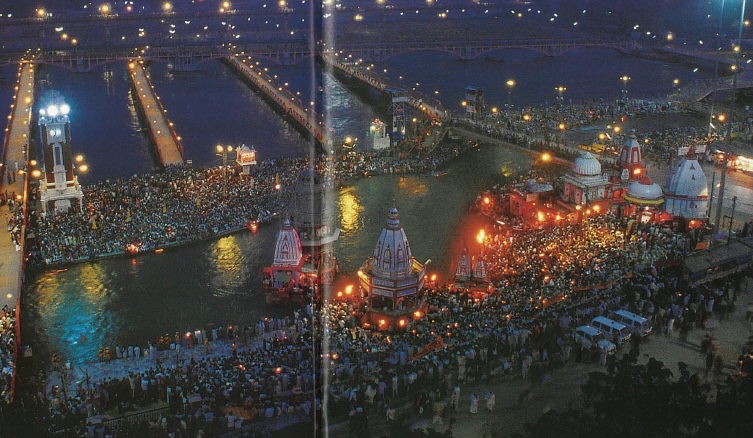

These pilgrims had come from all over India; some of them had been months on the way, plodding patiently along in the heat and dust, worn, poor, hungry, but supported and sustained by an unwavering faith and belief. It is wonderful, the power of a faith like that.” So stated American author Mark Twain, who witnessed the Kumbha Mela of 1895 in Allahabad, India. Now, in 1998, the same scene is repeated–almost–in the holy city of Haridwar, 180 kilometers north of New Delhi. Newspaper reports state 25 million pilgrims participated in the four-month-long festival, with ten million on the single day of April 14. The Kumbha Mela originates from a traditional story that drops of amrita, the divine nectar of immortality, fell at four holy places, including Haridwar. To share in this blessing, devotees bathe in the sacred rivers at each site on auspicious days in a twelve-year cycle [see pages 32-35 on the Mela tradition].

I was apprehensive as we departed Delhi on April 9, as a fight among the sadhus on March 25 which left some dead and a hundred injured [page 39] had only enhanced the very real danger of disastrous stampedes in the incredible crowds. “But what is there to fear?” Uday Kumar Singh of Uttar Pradesh asked to solace me. “Life is given by Him. One who dies in a holy place attains salvation.”

As soon as we boarded the Shatabhi Express, a religious calm settled upon me. The compartment was full of saints and pilgrims, some discussing the Kumbha Mela, others chanting “Jai Ganga Ma”–“Hail Mother Ganga”–while devotional music played over the train’s sound system. Upon arrival, we found Haridwar neat and clean, much better than normal. The cool evening river breezes were a relief from Delhi’s hot polluted air.

Every form of accommodation was crowded, hotels were charging outrageous rates, and most devotees were ensconced in vast tent cities scattered between Rishikesh and Haridwar, or sleeping under makeshift tarp shelters. Everyone was here, from Rajasthan, Orissa, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Nepal, and a smattering of nonresident Indians and nationals from dozens of countries [see page 7 interviews]. They came mainly to take a bath in the holy river at this auspicious period for the betterment of their spiritual selves. They could see and even meet some of the tens of thousands of saints and sadhus who converged here for the event.

Reporter Nikki Lastreto of California described the scene: “Everywhere were flashes of orange cloth, wooden sandals, jata (matted hair) and malas (recitation beads) made of rudraksha or tulsi. As I strolled down the muddy lanes where the akharas, or distinct clans of sadhus, pitch their camps, I caught glimpses of a lifestyle that dates back in time. Past millennia mingled with the almost-21st century as devoted chelas gently and lovingly massaged their guru’s feet while television sets glared and radios blared in the background.” One submission to modernity was the daily posting on the Internet of Mela events [see page 56].

With no vehicles allowed within Haridwar, pilgrims found themselves trekking ten to twenty kilometers a day. “My wife could not walk,” said Singh. “She got tired and started crying. The lack of transport has caused us a lot of inconvenience. Still, with so many people, vehicles would create a problem.” Singh praised the overall organization. “The arrangements were so systematic. We could easily bathe without hassle, and there were special ghats for women. Unlike the last Mela, there was no pickpocketing. We loved meeting people from all over India and the world.” Singh was obviously not a wealthy man, and complained the high food prices had caused his group to spend Rs.700 (US$17) each for their entire pilgrimage. Fellow Hinduism Today correspondent Rajiv Malik observed, “The pilgrims who flocked to Haridwar were of two categories–very rich and very poor. The middle class Hindus are indifferent to the occasion.”

A major boon for less wealthy pilgrims was the numerous langars, free feeding tents set up across the Mela area. Ram Swarup Shastri, for example, traveled 700 kilometers from Jodhpur in Rajasthan to set up the Ram Snehi Annakshetra which fed 3,000 pilgrims a day. Radheshyam Sharam of the Guru Nanak Annakshetra Bhandara was feeding 10,000 people a day with a staff of twelve cooks, and Shiv and Satish Kumar from the Punjab had 35 cooks serving 30,000 people daily. “We do not bother about money,” Shiv said. “By doing this, we get peace and satisfaction. We have become richer, not poorer.” By an intricate combination of langars, restaurants, ashrams and open-air cooking by devotees, tens of millions of pilgrims are adequately fed.

I would have thought local merchants were making great profits. But Ved Prakash of Shiv Ratan Kendra admitted, “There is not much difference in business. People are coming to take the bath, and with the police barricade, they are not able to stay long. So it is really business as usual.” Anil Gupta of Navaratan Kendra has four shops in Haridwar well stocked with religious items, but he too said, “It is mostly the ordinary, poor people who come to the Mela. We have more business, but you cannot call it substantial.”

Some of the pilgrims seek out their family panda, a local Haridwar priest. One, Kuldeep Gautam, said, “We maintain a record of devotees that is 300 years old, going back to the time of the Moghuls.” These priests assist with and record the rituals, especially the samskaras (rites of passage) for children such as head shaving.

Initially criticized as unprepared for the huge event [see page 41], the government administration won high praise for their handling of the Mela. More than 25,000 police were deployed throughout the area, and a larger number of army personnel stood by in the event of an emergency. The police worked 12-hour shifts, but found time to take their own bath in the Ganga each day. Said Deputy Superintendent of Police Harbans Singh, “We keep our fingers crossed that everything passes peacefully. In the evening when people turn up in large numbers at Harki Pauri for arati [offering of lamps–see photo opposite page], there are real challenges.” Constable S.P. Sharma said, “We perform our duty with namrata [easy-goingness]. We know these people have come from far-off places for their religious rites, so we do not use force to maintain law and order here.” The most common emergency was people swept into the swift waters. One of the 300 river police, Prabesh Yadav, said he had rescued 20 people, most of them women.

Getting lost was another very real hazard, and a huge system of information centers dealt with the missing. The lost–thousands a day–go to the centers and make an announcement in their own language which is broadcast on 18,000 loudspeakers covering an area of ten square kilometers. The one or two left at the end of the day are helped with accommodations by certain groups, and even given bus fare home.

Despite early fears, the final bathing day of April 14 passed without mishap, and we were on the train back to Delhi the same evening. There was so much to see, people in different dresses, different colors. While taking their bath, they looked heavenward with such sincerity, so much faith and trust! Hundreds of thousands were assembled here, still it was so very peaceful. As I was leaving, in everything I saw–people, shops, temples, roads, billboards–I saw the imprint of God.

I have also attended 1998 Maha Kumbh Mela with my mother. I was only 13 years old and studying in eighth class. We lived in Normal Bag Ashram, Kankhal during 12-04-1998, Sunday 1400 Hrs. To 15-04-1998, Wednesday 0800 Hrs. After Maha Kumbh Mela we went to Deoband to my Mama Jo’s Home.