Ongoing threats to life and property in Pakistan, compounded by the abduction, conversion and forced marriage of girls, continue to drive thousands to India

To say Hindu roots in Sindh—now in Pakistan—are deep is an understatement: a large part of the Indus Valley civilization, including Mohenjo-Daro, was located here. Hindus lived in harmony with their Muslim neighbors until the horrors resulting from Partition, which spared few. Those who remained—many too poor to flee—made the best of an uneasy situation, but an increasingly hostile environment is steadily forcing their descendants to escape to the safety of India. Once across the border, though, they endure an uncertain life for years in Rajasthan and other states. Here we tell two stories: of those who settled last century in Bhopal and those who have come since to Jodhpur.

BY LAVINA MELWANI, JODHPUR & BHOPAL

Lavina Melwani is a journalist who writes for several international publications. She blogs at Lassi with Lavina.

Web: http://lassiwithlavina.com

Follow: @lavinamelwani

WHEN YOUNG HINDU GIRLS GO TO school each morning in Sindh, Pakistan, their parents do not know whether they will ever see them again. Two Hindu sisters in Daharki in Sindh’s Ghotki district, both minors, were not even safe in their own home. According to a March, 2019, report in the New Indian Express, a group of “influential” men kidnapped 13-year-old Raveena and 15-year-old Reena Meghwar from their home while they were playing Holi. They were converted to Islam and forced into marriage with Muslim men. The same report says 1,000 Hindu girls are converted to Islam in Pakistan every year. They vanish, then reappear with Islamic names, married to Muslim men. Legislation to outlaw forced conversion was shelved by the Sindh legislative assembly in 2015 after protests from conservative Muslim groups.

A Los Angeles Times article from 2012 detailed the process: “Hindus say the forcible conversions follow the same script: The victim, abducted by a young man related to or working for a feudal boss, is taken to a mosque where clerics, along with the prospective groom’s family, threaten to harm her and her relatives if she resists. Almost always, the girl complies, and not long afterward, she is brought to a local court, where a judge, usually a Muslim, rubber-stamps the conversion and marriage, according to Hindu community members who have attended such hearings. Often the young Muslim man is accompanied by backers armed with rifles. Few members of the girl’s family are allowed to appear, and the victim, seeing no way out, signs papers affirming her conversion and marriage.” (bit.ly/Pakistan2012)

Gut-wrenching experiences like these have caused thousands to leave home in search of spiritual freedom, security and justice for their daughters. It is estimated that at least 10,000 Hindu Sindhis have fled to India in just the last seven years.

Even 72 years after Partition, daily life remains traumatic for many Hindu Sindhi families in Pakistan. Their religious freedom and their ability to embrace their spiritual culture and traditions remain in jeopardy. They endure persecution, scarce ways to earn a living as a minority in an Islamic country, and the danger of their young daughters being kidnapped and pushed into forced marriage and conversion to Islam.

For Hindu Sindhis, Partition has never ended. Even today they struggle for their basic human rights to pray to their God and bring up their children in the ways of their forefathers. As Meera Bai, a Hindu who fled Pakistan, told the media, “Muslims in Pakistan will never treat Hindus as their own. For them, we will always remain the ‘other.’ We escaped religious and cultural persecution when we came to India. We are happy here. At least here we know that no one will steal our cattle or our daughters.”

Professor Satya Narayan of Jodhpur echoes. “The growing religious radical fundamentalism is so widespread that there seems to be no safe room left for minorities, particularly in Pakistan. Minorities are facing forced conversions and marriages, abductions, land grabbing, rapes, murders, kidnapping for ransom, fake blasphemy cases leading to minority settlements being set on fire and people being burned alive, disgracing dead bodies of Hindus and attacking, setting fire to and demolishing of Hindu temples.”

For These Lucky Children, a Chance at a Good Life—Eventually

As Narayan points out, not only are Pakistan’s minorities unsafe as nationals in Pakistan, they have no basic rights as migrants in India. The latter was not a signatory—for geopolitical reasons—to the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees. India nevertheless accommodates the refugees and provides them a path to citizenship, albeit a very long one.

This topic has always been central to my life because I, too, am the child of Sindhi refugees who fled from Pakistan at the time of Partition. All our lives, the Partition narrative has been a part of our existence. I particularly remember a photograph of my father, who was a jeweler, standing grimly besides his sealed shop. His shop and home were confiscated and he received no compensation. He came to New Delhi as a refugee with five children. Fortunately, he had good friends and was able to restart his business and a new life in the new India.

Over the years, Sindhi refugees have continued to come by train, bus or on foot to areas near the border in Rajasthan and Gujarat where they try to start a new life. I proposed to HINDUISM TODAY that I visit to get a first-hand report on how these newest and youngest survivors are faring as they walk the tightrope of refugee life between Pakistan and India. I also visited in Bhopal the community of Sindhis formed by those who fled Partition in 1947.

Human Rights Work

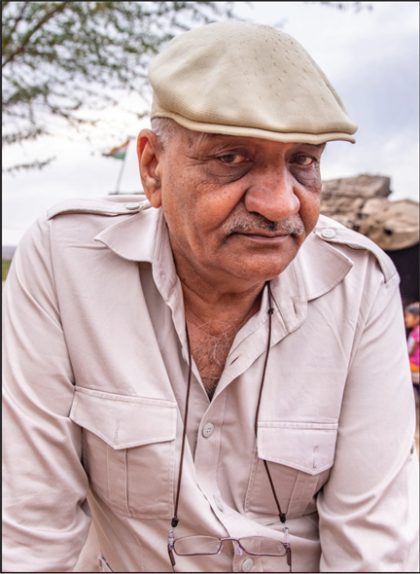

For most, the Hindu Sindhi refugees are a forgotten people for whom the fast-moving world does not have time. Yet they have a friend in Hindu Singh Sodha, who himself fled from Chachro in Tharparkar, Sindh, to Jodhpur, India, just before the 1971 Indo-Pak war. A law graduate from Jodhpur University, he has spent two decades in the city, greeting many of these first arrivals who had neither a place to stay nor food to eat. From the 90s he has worked as a human rights activist, and he founded Seeman Lok Sangathan and Universal Just Action Society (SLS/UJAS) to help rehabilitate the Pakistani minority migrants. One media article has referred to the gentle yet determined Sodha as “the god of small people.” He and Ashok Suthar, also a refugee and social activist (whom we will tell more about later), served as my guides in Jodhpur.

According to Kavita Tekchandani, a lawyer and community activist who works with UJAS from California, there are currently 85,000 Pakistani Hindu refugees who have crossed the border into Rajasthan, India, due to the recent instability in Pakistan. Most come from Sindh, Southern Punjab and Balochistan. She says, “Like other religious minorities, they have become soft targets for crime, and many have faced issues with discrimination, kidnapping for ransom and kidnapping for marriage, forcing a trickle migration.”

In his book Fence without Fencing, which he has coauthored with Ashok Suthar, Tekchandani mentions how 13,000 migrants succeeded in getting Indian nationality through UJAS support.

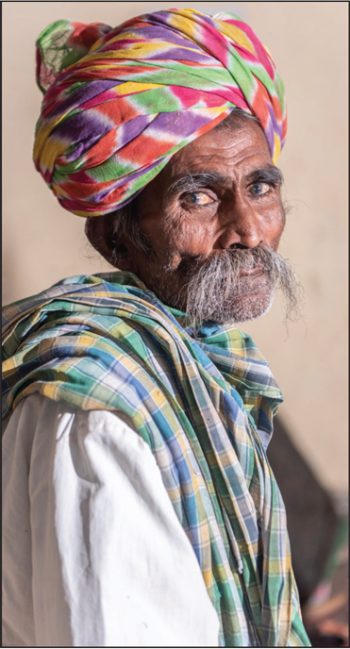

According to Sodha, most of the migrants coming into western Rajasthan are Hindus of different castes, such as Mehwals, Bhils, Kolhis, Odhs, Rajputs, Brahmins, Suthars, Sonars, Prohits, Jats, Nais, Darzis and others. Most are low on the economic scale, with scant resources at their disposal. Many come to India on pilgrimage visas. Sodha estimates in his book that the current total population of recent Pakistani minority migrants in India, increased through births, is nearly one million. Most are staying in Rajasthan, then Gujarat, followed by Madhya Pradesh and some other states. The new migrants go through many difficulties—they have to wait at least years before they can be eligible for citizenship, and during a least part of that period they cannot leave the city where their visa was registered. They have difficulties in obtaining homes or driving licenses, among other problems. A recent article from Aljazeera new service quotes Sodha as saying, “[Indian] government officials often pose unwarranted questions, such as who do they call up in Pakistan and how many times they call.” Such actions add to the refugees’ sense of insecurity.

“This group is not helped by the government, and none of the national and international human rights organizations have yet shown an interest in taking care of their agonies,” stated Sodha. “They are deprived access to basic rights, including the right to justice, the right to self-recognition, the right to work, education and healthcare.”

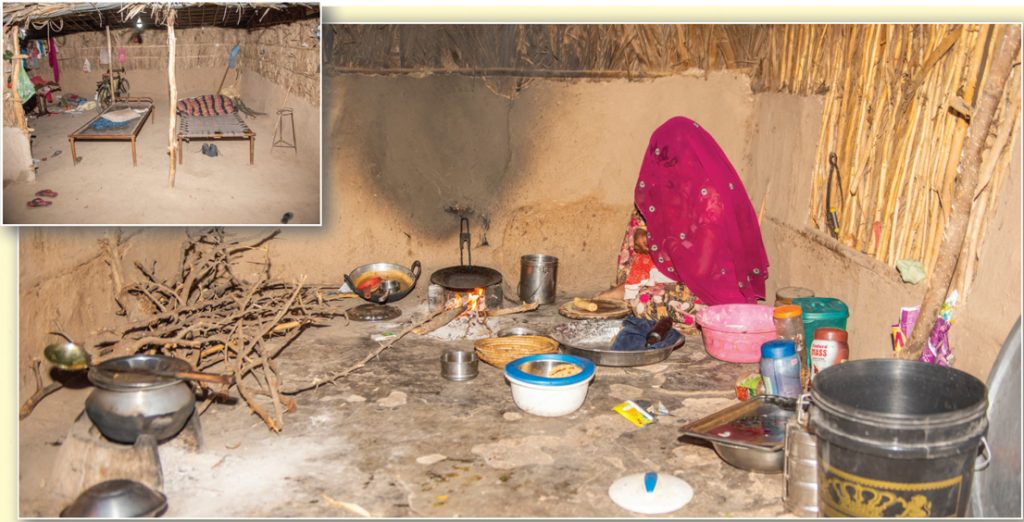

They come to India for the intangible concepts of religious and economic freedom; but settling into camps in the Rajasthan border areas, these refugees have almost no electricity, no clean drinking water, limited food, no shelter and very few resources. Many are being treated for malnutrition in addition to other conditions.

“Currently it is estimated that about 250 to 500 people are coming into the Jodhpur temporary camp grounds every two weeks due to the rise of violence across the border,” stated Tekchandani. “Without proper work permits and legal status, they are living in a no-man’s land. They feel unsafe to return to Pakistan, yet they cannot easily earn their livelihood in India.” According to Sodha, they are engaged in street vending or working as day laborers on farms, in rock quarries, in the handicraft industry or other such arduous work.

The refugees can only gain Indian citizenship after living in India for 11 out of the preceding 14 years. They wait in makeshift camps, without the means to work and legally live in India. Sodha claims that some give up, return to Pakistan and convert to Islam simply to survive. If India were to sign on to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, Pakistani Hindu migrants and others who are victims of violence, or who have a well-founded fear of persecution based on their religion in their home countries, would be given the opportunity to gain legal residence permits on an as-needed basis.

Mud Huts and Sparse Belongings Define Refugee Life

At a bare minimum, Tekchandani recommends, India should provide basic resources for the Pakistani Hindu and other persecuted refugees upon arrival, including tents, clean water, medical care, and means for children to transition into local schools to avoid disruption in education. Further, these migrants should be subject to less wait time for legal work permits, in order to more quickly become self-sufficient and less vulnerable to exploitation.

According to UJAS, which works with migrants, these families are poverty stricken. Many have the status of scheduled castes and tribes, and they become more susceptible to discrimination and exploitation when they are further stereotyped as women and children of Pakistani migrants. UJAS is working with local government organizations to help get the rights, visas and citizenship of these migrants addressed.

Aanganwah Refugee Camp

It was heart-wrenching to visit the dusty wasteland of Aanganwah refugee camp about nine miles outside of Jodhpur with Singh and Sodha, and meet the refugees face to face. The squalor here, in the midst of sparsely occupied farmland, was in stark contrast to the lovely city of Jodhpur we had just left. Here the small community of refugees live in mud dwellings with thatched roofs, tending their cattle. It is a nowhere land with no electricity, no nearby stores or medical facilities. Seventy percent of the refugees have lived here five years or more; others are as recent as two months. Rough and hot, with rocky, dusty ground and no paved roads, this is their new home. There are about 300 households in this area with a total population of 1,550 people, nearly half of them children. Currently four NGOs are working in the community with the government, assisting with schooling, midday meals and health camps.

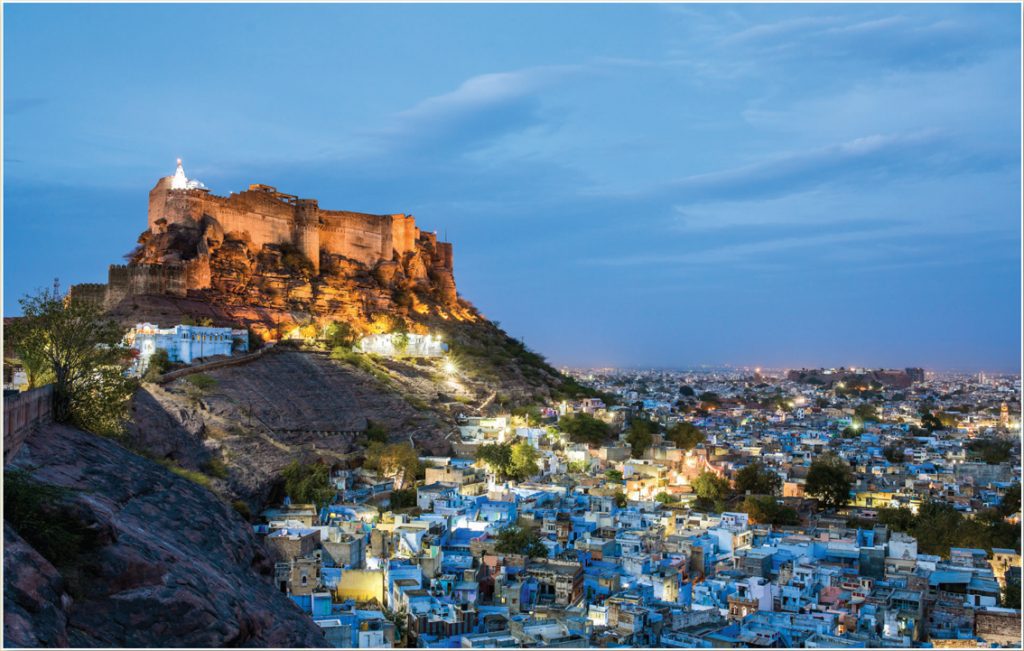

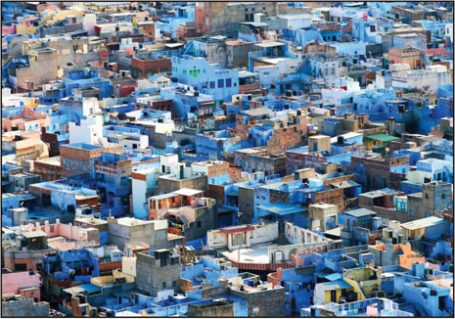

Jodhpur, the “Blue City”

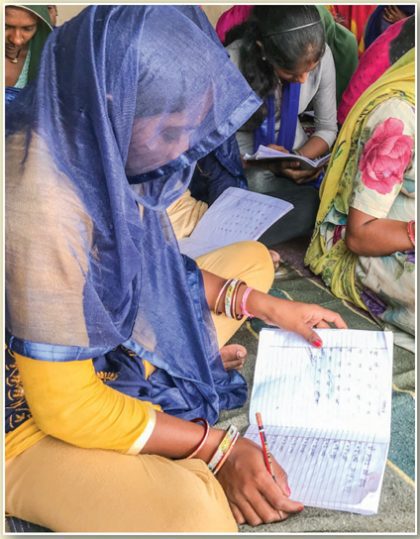

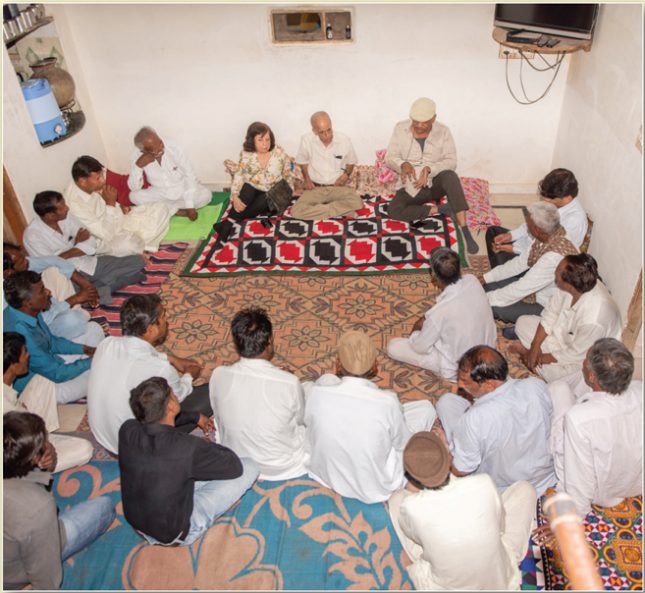

We had an open-air panchayat, community gathering, sitting on spread-out dhurries—the thick carpets which are a speciality of Rajasthan. Hot tea was passed all around as men, women—many with ghunghats veiling their faces—and children gathered around us and discussed their concerns. On request, the young girls came forward and told us about their new lives. They spoke about being enrolled in high school, and one of them happily shared her plans to study medicine. But overall this was a very subdued group of people, the adults quiet and withdrawn and the children abnormally reserved. We walked around the area with them and were taken inside some of the humble mud homes, which were furnished with the most basic of necessities—string charpoy beds, for example, wood for cooking and metal trunks for their few possessions.

One of the first structures built by the refugees in the Aanganwah refugee settlement was a temple to bless their new endeavors in a new country. They had traveled hundreds of miles and faced dangers to gain this basic right. Here they can worship freely with no restrictions. It is here that they celebrate all Hindu rituals and festivals, without fear of reprisal or abduction.

At the UJAS office, which is some distance from the camp, we met the small, dedicated staff and ate a vegetarian meal with them. One of our guides, Ashok Suthar, is himself a recent refugee who left Mithi, Sindh, to safeguard his young daughters. A graduate in sociology from the University of Sindh, he has authored several books on social development and devoted himself to working with migrants. He mentioned that most of the refugees are tribal families and their children have great needs, as many are illiterate or can only communicate in Sindhi.

As we spoke, Neha, his lovely daughter, now in her teens, returned from high school, smiling radiantly in her white school uniform and talking excitedly about a career in fashion design. I knew Sodha had made the right decision to risk the unknown to come to India. Had they stayed on in Pakistan, there is a strong chance she would have had a very different life.

A Family Celebrate Their New Citizenship

Later we visited another camp in the heart of the city where Sindhi migrants were also housed. This camp had more conveniences, such as furniture and modern cooking equipment. It was a solid brick-and-mortar building where the migrants weren’t at the mercy of the elements as were the refugees in Aanganwah. Here they had proper kitchens, bathrooms and electricity. Still, they looked shell-shocked and grim, and the children didn’t laugh and play in the carefree way children normally do.

Gradually, life does get better for the refugees. We visited a private home in the city where many of the earlier Sindhi migrants had gathered to meet us. They were boisterous and happy, as some had just got their citizenship papers after many years. We were served hot tea and samosas; there were garlands for us and a fancy turban presented to Hindu Singh Sodha to honor him for the work he does with the migrants.

Our host was a successful refugee who had been here for several years. His home was a comfortable three-floor apartment. His three sons had set up several shops in the area, and the children, even the little daughters, were playful and confident. They all attended school in the area. It was as good a life as it can get—and there were unexpected bonuses too. I was pleasantly surprised to see that one of the stores which sells fabrics and women’s clothing was run totally by women—the daughters and daughters-in-law of the house. Their heads were covered in decorous Sindhi small-town fashion, but they were clearly independent, making a living and being the boss—something which would never have happened in Pakistan.

Preserving Language and Culture

In an attempt to help safeguard the refugees, the Hindu faith and the fast-fading Sindhi language, supporters in New York as well as the UJAS and other NGOs in India are helping these latest refugees establish a community center and school in Jodhpur. As we went to press, I received the first photographs of the launch of the UJAS Asha Kendra being funded by Children’s Hope India, a New York organization I am affiliated with. It was satisfying to see the ribbon cutting of the temporary school building as the permanent structure is being built. The teachers have already been hired. Now these children will not have to walk many miles to school; they will travel by school bus, for which the funds are being raised in New York. Here they will learn Hindi, the national language, which will make them a part of their new homeland of India. They will also learn English. Sewing machines are available for the women; there is a new skills-training center and there are plans to help them market their creations.

On my last day in Jodhpur, I visited the famous Clock Tower open market. This is a big tourist attraction and is also a vital market for the locals. It has everything from groceries to clothing at reasonable prices. Some 80 percent of the businesses are run by former Sindhi refugees, who with their perseverance and enterprise have literally cornered this market. One of the most popular businesses is a spice chain run by seven young sisters, the daughters of a former Sindhi refugee. They are known as the Spice Girls, and so successful is their business that tourists flock to their three bustling stores. Even the tourist bible Lonely Planet has written about their famous spices.

The business of the seven sisters had its origin in the fresh spices their refugee parents used to grind in the camps back in 1947—the only work they could do in the desolate camps. Like most Hindu refugees, they have taken a difficult time in their lives and turned it into the foundation of their future.

Seventy Years Later, Bhopal’s Sindhis Have Made Good

Bhopal, Where Sindhis Have Thrived Since 1947

THE RIGHT TO PRAY TO ONE’S GOD IS FUNDAMENTAL. Rather than lose this right, many Hindus, faced with the bloody, traumatic partition of India in 1947, chose to flee what became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan for the freedom of the new secular India. In the mayhem that followed, hundreds of thousands of Hindu families lost their homes and livelihood, their properties and their loved ones. They arrived in India as refugees, dazed and broken, often not knowing how they would survive. Yet they had come to a place where they could breathe free and practice the faith of their forefathers openly. Spreading all over India, the Sindhi refugees struggled and made new lives for themselves.

They settled in large numbers in Bhopal, the capital of Madhya Pradesh, where today there is a thriving Sindhi community—an inspiration to the new refugees languishing in and around Jodhpur. Among the original refugees was Paramhans Sant Hirdaram Sahibji (1906–2006), who founded the Jeev Sewa Santhan (JSS) to look after the needs of the community. A spiritual head to the Sindhi community, Sant Hridaram worked to help the needy and infirm. He believed in the power of education for strengthening a new generation—especially women. He saw to it that all Hindu holy days, including the Sindhi festival of Cheti Chand, were celebrated joyously and in the open. Bit by bit, he rehabilitated and gave spiritual sustenance to the Sindhi community.

Many of the Partition survivors have passed on, but I met with several—now quite aged—to hear of the ordeals they encountered in order to retain their Hindu dharma. Most, I was told, first took shelter in rough refugee camps in Rajasthan, then moved on to Bhopal where they were given land in Barrackpore. Like Barrackpore in West Bengal, the city was named for its large numbers of British army barracks. The abandoned barracks became home for the refugees

Some, like Hazari Mal Bacho Mal Khubchandani and his family, still live in these barracks, where in railroad fashion one room leads into the next. He is a youthful 95 with a yellow turban and a bristly white mustache. His wife, now 85, cannot walk much and likes to sit on a chair beside her home shrine and pray. The couple have 14 children, many grandchildren and a thriving number of businesses, including footwear factories.

Khubchandani was just 23 when he came to India. Even today he is ramrod straight, and he credits that with his job of milking the family cows and looking after them. He still continues to work as a bidi (tobacco) entrepreneur. In a very millennial way, he has built his brand around himself: his turbaned profile appears on every pack of bidis!

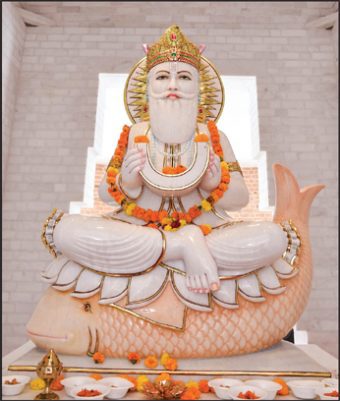

Educational and Medical Facilities Benefit Entire Community

Why did he leave Pakistan? He recalls life in his homeland: the Hindus were a small minority but had lived side by side with Muslims, who were often their barbers, their weavers and their cleaners. They each worshiped their own Gods, and harmony prevailed. He feels it all changed when politics entered the picture. Doubts and suspicion set in at the time of Partition. They could not sell their properties at any price, because everyone knew it would all eventually belong to the Muslims. Leaving home with very little, the Hindus put their faith in Jhulelal, the ishta devata of the Sindhi people, and set out into the sands of Rajasthan.

Khubchandani spoke wistfully of their lost homeland: “I miss that. It was a simple life where family and community was everything. When guests wanted to depart, we would confiscate the reins of their horse carriage because we did not want them to leave and would insist they stay on!” Such was the love and hospitality among the Sindhis, a heartfelt and pure way of life and belief which is hard to duplicate in a fast-changing India.

In Bhopal, too, of course, the Hindu Sindhi hospitality is a given. Our meeting was joined by an ever-expanding circle of Khubchandani’s extended family—sons, grandsons and great-grandsons, sons-in-law and daughters-in-law. They plied us with thick, sweet, milky tea and snacks concocted by Sindhi entrepreneurs—chickpea or besan murmula, Sindhi chikki sweets and peanuts. Later we met the matriarch around whom the family revolves, including seven daughters-in-law. All live together in the sprawling, renovated barracks which now house their businesses too—fabric stores, grocery stores and other small retail businesses. On the apex of the building is a sculpture of Lord Krishna.

The family told me of Khubchandani’s great devotion to cows and his one favorite cow that he called Amma or Mother. All 14 of his children were nurtured on her milk. He feels his cows have kept him fit over the years as he has looked after them personally and milked them all. When his beloved Amma cow died, he built a memorial to her, and on every death anniversary they hold prayers for her.

The Sindhi community showed me a few other barracks which have survived. In one, the sole occupant is a 90-year-old woman. We did not meet her, as she was traveling to see relatives. Her family have done well in government jobs, but she refuses to move in with them, so independent and attached is she to her dilapidated barracks home.

After 72 years, she still does not have possession of this home. The family is fighting the case. Khubchandani, too, has no papers to his home, and he, too, is waiting for reparation from the government, 72 years after Partition. Many refugees have died, still waiting to get justice and the title deeds for the property in exchange for all the land and property they had to abandon when they left Pakistan. Yet, it is a positive community which moves on and is involved in the present, not the past.

We next visited Gobindram Kewlani, who at 90 is more articulate than many of us and heads the Sindhi Panchayat, which works with the local government in seeing to the welfare of the Sindhi community. He also collects and donates wedding attire, jewelry and home products to help young Hindu girls from needy families get married. He is known to the whole town as Mama or Uncle because he continues to look to the interests of the community. When we met him, the elections were around the corner, and he was busy organizing the Sindhis for a Congress rally so the community would get their rights. As we left, the aroma of hot fried samosas was in the air. Crowds swirled and loudspeakers blared out the life of current-day India—and 90-year-old Mama Kewlani was a cheerful, vibrant participant.

Hindu Sindhis are part and parcel of Bhopal and have greatly enhanced its economy. Starting from scratch, they have given life to Bhopal’s famous Market of Utensils and Market of Fabrics. The earliest refugees rolled papads, made pickles and sorted spices in the camps, and the manufacturing of food products became a practical way of making a living. This enterprising and quick-witted community sells everything from street food to packaged goods.

Few restaurants offer Sindhi food, but one Sindhi entrepreneur has started a chain called Manohar Restaurant—three famous restaurants with vegetarian food and special mithai sweets. Now the third generation is getting into white-collar jobs, with many holding government jobs.

A local stalwart, Mr. Babani, says that today there is no city in India where Sindhis are not present or have not made an impact. They have become doctors, engineers and are also in public service. The Sindhis have organized panchayats, grassroots organizations across Bhopal so that they can have a say in the political and civic life.

With the Bhopal Sindhis every Hindu festival and holy day is celebrated boldly, joyfully, the most natural thing to do—a hard-won right for these devotees who trudged across the deserts, lost their ancestral land but never gave up their faith or their God. Unfortunately, many younger Sindhis have gradually lost their language, which is not taught in the mainstream schools. Language is often lost by migrants as they try to assimilate into a new culture. Vigilant parents have tried to keep it alive at home, and activists try to inculcate the language and writing skills in the young people both in India and the diaspora.

In the busy marketplace I met Raj Kumar Mangtani, a Sindhi entrepreneur whose grandparents were refugees from Sindh. Along with his father and brothers, he presides over a bustling three-floored shoe emporium. He said that in spite of their business success, for the last decade their interest has primarily focused on the education of their children and ensuring that they succeed in whichever profession they choose.

The work of JSS has continued through the years, aided by an unheralded army of supporters—successful Sindhi Indian entrepreneurs who had sought their livelihoods in far-off countries and are now ready to give back. Many of these Sindhi benefactors are themselves refugees or the children of 1947 refugees, and with their financial help JSS has built several institutions for the poor and middle-class people in Bhopal.

Over the years JSS has built a large campus with seven schools, five colleges and an eye hospital, all created by donations from Indians of the diaspora, from Hong Kong to the US, Singapore and Dubai. Every institution has a temple and celebrates the values of the Hindu faith.

Due to the enterprising efforts of this small Sindhi community, the town once known as Barrackpore has come to be known as Sant Hirdaram Nagar. Today Hridaram’s successor, Hotchand Dhanwani, named Siddh Bhau by his guru, runs this massive network of hospitals, schools and colleges. Siddh Bhau is the spiritual and social champion of the Sindhi community who continues the legacy of Sant Hirdaram through JSS. He is assisted by Mahesh Dayaramani, who is the catalyst who connects overseas donors to the projects and makes things happen.

The majority of the local Sindhi children are graduates of the schools and colleges founded and created by Jeev Sewa Sansthan, where Hindu Sindhi spiritual teachings are a part of the education. A large number of local non-Sindhi children also attend. Respect for elders is part of the curriculum, and touching the feet of teachers every day is part of the routine. Every school has a small Hindu temple. The morning begins with a 20-minute assembly with prayers and the national anthem, followed by classes including everything from science to computer education.

On our final day we visited Siddh Bhau. He lives in a simple cottage in the shadow of a Hindu temple dedicated to the saint who gave Bhopal Jeev Seva Sansthan. At that moment it was crystal clear that the Sindhi community in Bhopal had prospered due to the spiritual strength and moral fiber offered by JSS. The network of schools, colleges and hospitals as well as the familial caring for widows and children had set the moral compass of the community.

Far from Home, But Holding Strong

The name of Sindh is sung in the national anthem, Jana Gana Mana, but Sindh is no longer part of India. The Indus River itself—source of the words Hindu and India—was partitioned from India. The Sindhis are the only people in India without their own state. Their beloved homeland may be thousands and thousands of miles away in an alien country, but the heartbeat of the Sindhi ethos and culture remains strong in these migrant people. They have internalized Sindhyat, the distinctive features of the Sindhi community, and all that it stands for.

For Sindhis and Others, a First-Class Education

Very Sweet Success for this Sindhi Family