The scented wood, precious since Vedic times, becomes more rare and expensive year by year. Two decades ago Australian firms began planting what are now massive groves in their northwest territories, where conditions are ideal. Now economics, not nature, have bankrupted their largest plantation due to the long pay-back period. In this article we explore the art, science and financial perils of the legendary substance.

HINDUISM TODAY found itself in the unusual position of revising this article days before our press deadline: Quintis, the company we profiled in depth, unexpectedly went bankrupt after failing to meet a us$30 million loan obligation. It wasn’t a failure of forestry expertise—they are growing sandalwood trees by the square mile—but of business management and financing. While the company is now in receivership and investors stand to lose money, the plantation will likely survive. But let us first tell the rather glowing Quintis tale we collected in 2017 before discussing the details of a promising company’s travails.

It’s only mid-morning in kununurra in Western Australia’s far north, but the air is already heavy with the promise of the heat to come. Andrew Brown knows the importance of starting the day early up here, so he’s been at work for hours, walking up and down the sprawling stands of Indian sandalwood he’s here to inspect—just one small section of the 5.4 million trees spread over the immense 47-square-mile Quintis company plantation. In his role as Head of Research and Development, Brown has spent ten years caretaking this precious tree, from its planting to the extraction of the golden oil.

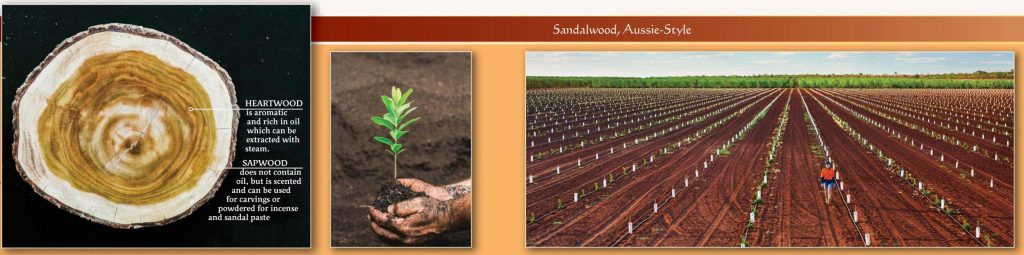

World’s largest sandalwood plantation: (counter-clockwise from below) cross-section of a mature log; seedling ready for setting in the field; a new multi-acre planting; just one section of Quintis’ 47 square miles of trees; (inset) plantation location in Kununurra

Harvest of this section is only three weeks away, so to find any signs of damage now would be a hard blow. Indian sandalwood (Santalum album) is an endangered species, one of the rarest tree crops in the world, and takes 15 years to reach harvestable size. Its precious oil, highly prized since ancient times for its healing properties and rich fragrance, commands thousands of dollars per liter. The trees once grew throughout South and Southeast Asia, but overharvesting and unscrupulous black-market trade have taken a heavy toll. This plantation which includes hundreds of individual growers under contract and nestled in the lush, tropical Australian northwest—if it survives bankruptcy—would be the only commercial, sustainable sandalwood enterprise of its size anywhere in the world.

Ideal Site, Unmatched Expertise

Australia’s Ord River Irrigation Area was developed in the 1960s and 70s, first for cotton and sugar, later for fruit and vegetable crops. Rich with water and fertile soils, the region is reminiscent of India’s sandalwood plains. Drawing upon decades of research from India, the state’s forestry department conducted successful plantation trials of Indian sandalwood. Quintis was formed in 1997 and began planting seedlings in this remote corner of the county almost 20 years ago.

“Album is a true tropical species. It loves hot, moist, monsoonal summers and cool, dry winters, and those are exactly the conditions we have across northern Australia,” says Ken Robson, the head of forestry research.

The early years proved challenging as foresters gradually discovered the secrets to growing the hemiparasite sandalwood tree. It requires a complex ecosystem of host plants (up to four) during its growth. Working from experiments by experts in India, growers identified and incorporated into the plantings host plants suitable to local conditions. Survival rates improved in a matter of years, and the trees began to flourish.

Early on, the company set about selecting genetically superior material. “Everything is about maximizing heartwood, so you want to create straight, thick trees. This means you want to be breeding trees that have these characteristics,” says Andrew Brown.

“Especially in the early years you could easily see the difference between the trees that had good genes, and those that didn’t. Now we have the luxury of being able to select the better trees to create more productive and vigorous plantings, but the real results of this won’t be seen for many years.”

The long-term outlook is key, explains researcher Robson. “My role is to continually look for new and innovative ways to improve our plantation.” A recent trial, for instance, was designed to identify host trees that use less water, in a move set to generate environmental benefits. Patience, Robson explains, is key to such research. “They’ll get planted out in field trials, and we’ll run those for a minimum of three years before we can actually start to see their true potential as a host,” he states. “Sandalwood is important for billions of people across the world, for spiritual and cultural reasons. I’ve spent almost all of my working career with sandalwood, one species or another, so I’m very familiar with it, For me—personally—it’s like an old friend.”

A Rich History

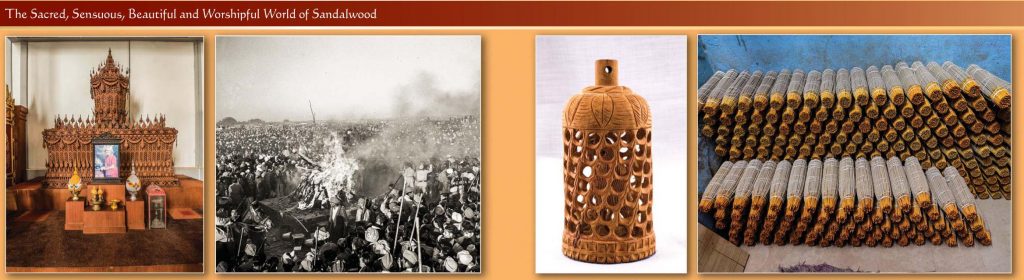

In ancient times sandalwood was as prized as jade or gold, and said to elevate its owner to godly status. In Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine it was prescribed for everything from curing stress to achieving enlightenment—and recent scientific research has lent some weight to these claims. Its intoxicating fragrance is as lusted after today by modern French perfumers as by ancient Indian royalty. Indian sandalwood oil is arguably one of the most coveted liquids in history.

“Anyone who was anyone had to possess some and to use it,” says historian James McHugh. “No king could be a king without it, and it was essential adornment both for important people and for the Gods in temples.” In ancient Egypt, the oil was used in burning rituals to venerate their Gods, while Hindus use an Indian sandalwood paste made by priests to decorate the murtis of Deities. The first known statue of Buddha was made from Indian sandalwood.

“Even within India it was seen as somewhat exotic, from far-away places, dangerous mountains in the South, or magical distant islands,” says McHugh. “Many references in poems and proverbs mention the idea that the sandalwood trees are infested with snakes—and thus both beautiful and lethal.”

While modern scientists have found sandalwood no more or less favored by snakes than other trees, it’s still a fitting metaphor. Movies have been made of the infamous sandalwood thief Veerappan, who terrorized parts of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu during a decades-long career that included killing 20 police at once with land mines, and kidnapping for ransom Rajkumar, one of India’s most popular actors. As recently as 2015, 20 people died in a furious struggle between Indian police and sandalwood smugglers, as did Veerappan himself in 2004 police action.

Even Australia is not immune to sandalwood theft, though without the bloodshed. Acting in stealth, thieves attack stands of native Australian sandalwood. A 2013 report by ABC’s “Bush Telegraph” news service states, “Hundreds of tons of Australian sandalwood are stolen by brazen thieves in Western Australia each year.” A 2017 ABC report quotes a government spokesperson as saying, “We have anecdotal evidence that there are millions of dollars worth of illegal sandalwood and oils being sent out of Australia every year.” This is not Santalum album, the Indian sandalwood grown by Quintas, but a close relative native to Australia, Santalum spicatum, which can pass for Indian sandalwood and from which good oil can be extracted.

The present situation with sandalwood in South India can be traced back to 1792, when the Sultan of Mysore made sandalwood’s kingly ties official by declaring it a royal tree, meaning no individual could grow it. That law stood in India until 2002, with all sandalwood owned by the government. The sandalwood tree growing in someone’s back yard was government property, and the landowner was held responsible if the tree was stolen. Unfortunately, this policy produced unintended results: to avoid liability, landowners would cut down small sandalwood trees as soon as they were identified and before the government became aware of them. Under present law, the individual owns the tree, but it can only be cut and sold with government oversight.

As the gap between supply and insatiable global demand grew ever wider, prices surged since 1960 and very much from the 1990s. A black trade worth millions of dollars was born. It’s been estimated more than 80 percent of Indian sandalwood in the marketplace is sourced from illegally harvested wood. Often trees are axed well before their time, and the market is flooded with inferior products. According to conservationist Susan Leopold from United Plant Savers, sandalwood has been teetering on the edge of extinction, though it is now recovering.

Harvesting, Australian Style

In their own best interests, the Quintis company carefully documents the production and harvest of their trees and the extraction of oil. This not only insures a uniform product but also assures buyers they are not contributing to the illegal trade. As well, these records assist with Quintas’ research into breeding more productive trees. At present, they harvest after 15 years of growth, which is really the minimum. After 30 or 45 years the trees would contain a great deal more heartwood. But business investors can’t wait that long for a return on their money, so the company must do the best they can in a shorter time span. The trees are long-lived in the wild, 500 to 800 years.

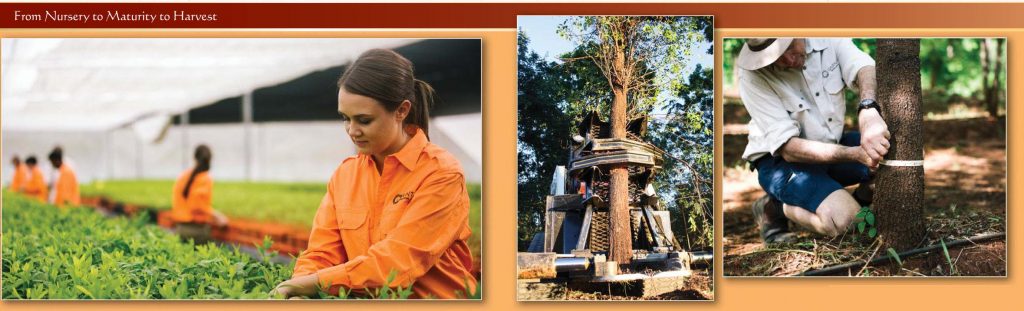

Plantation harvesting is a meticulous process. To preserve the precious heartwood, a “feller buncher” machine grasps the tree and cuts it off at the base. The attributes of each harvested tree are recorded for quality assurance and research purposes. A separate machine cores the rich, oil-bearing heartwood from the stumps. The wood is then transported to a processing center where it is finished and treated, readied for distillation into oil, or sale as finished heartwood used for carvings, handicrafts and worship.

The process: (left to right) tending the tens of thousands of seedlings for the next planting; a “buncher feller” grasps the tree and cuts it off at the base; measuring the tree’s girth, a standard marker of its growth

The Oil: Part Art, Part Science

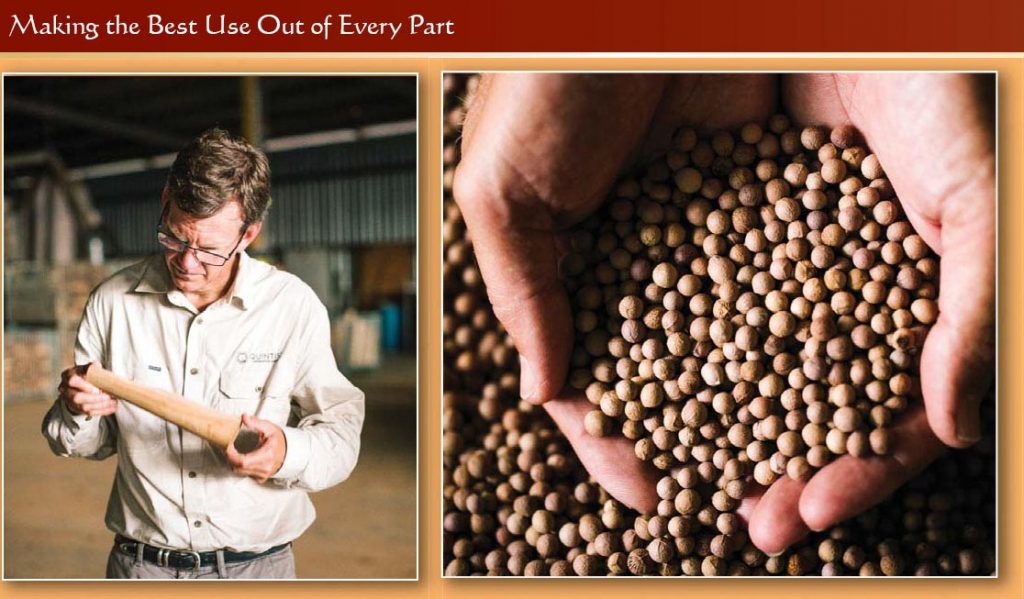

Each ton of heartwood will produce just 32 kilograms of oil. With its powerful fragrant and medicinal properties, the oil can be used in thousands of products including cosmetics, lotions and fragrances.

Familiarity with the subtleties of scent—and the language used to describe them—is an important skill the company’s team is required to possess. Andrew Brown, head of research and development, explains: “You have to be able to interpret the oil; there’s an artistic component in determining if it’s going to meet the specification of the client. If it doesn’t, then you need to know what to blend with the oil so that it does.”

Just like wine, the production of a high-quality oil requires a deft touch; a mistake at any stage can compromise the output. “After the harvest, you can stuff things up [that’s Aussie for “make a foolish error resulting in failure”] by not handling the wood appropriately,” says Brown.

Products and processes: Andrew Brown, head of Quintis’ research and development, inspects a billet of sandalwood; fresh wooden beads made for religious use; part of the steam distilling process by which oil is extracted

Blending is another delicate process, one taken into consideration from the very beginning. Sandalwood harvested from the base of the tree has different characteristics from that grown near the top. “You also get inter-tree variation, but that’s not such a problem,” says Brown. “After the wood is processed, we test the chips to get the oil information, then mix them in order to create a standard product.”

The oil is extracted in a four-day process in which steam is passed through the wood chips, causing the oil to rise to the top where it is collected. “Steam distillation is one of the least invasive methods of extracting oils from plant material,” explains Brown. “It is a physical process, not chemical, so the nature of the product doesn’t change. You need to distill the essence that you want, without also producing molecules that you don’t want. The art is in creating an oil that smells the way it should.”

Meditation and Medicine

“There’s nothing quite like Santalum album in terms of its effects on the mind and the skin,” states aromatherapist Robert Tisserand, who wrote The Art of Aromatherapy. “We know it has a calming, sedative affect, with sedative constituents finding their way into the bloodstream in tiny amounts.”

Other studies show Indian sandalwood oil can induce a feeling of well-being, triggering the feel-good neurochemicals dopamine and serotonin. It also inhibits delta opioid receptors in the brain, which are linked to major depressive disorder. “This suggests the possibility of an anti-depressant, mood-uplifting effect—much like the desired effects of meditation,” says Tisserand.

Practitioners of reiki, a Japanese form of healing developed in 1922 by the Japanese Buddhist Mikao Usui, use sandalwood oil to help clients tap into a higher plane of consciousness. Says one, “It works on this energetic field—almost as if the oil is dissolving and going onto a new level. It smooths out the chakras if they’re out of balance.”

The pharmaceutical-grade standardized oil is producing important developments in health care as modern physicians discover the wonders of sandalwood. In 2010, dermatologist Dr. John C. Browning of San Antonio, Texas, was approached by the biopharmaceutical company Santalis (a subsidiary of Quintis) to develop prescription skin-care medication from this high-grade oil. In Dr. Browning’s practice he had treated people of all ages suffering from eczema. Frustrated with the current steroid-based treatments, he was eager to find something better. After reviewing the data on sandalwood oil’s anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial and anti-viral properties, he concluded that “it would be a great treatment modality for atopic dermatitis.”

Browning conducted an eight-week clinical trial with 32 children suffering from mild, moderate or severe eczema. He had them soak in a sandalwood oil cleanser bubble bath and apply a sandalwood-oil based moisturizer to the affected areas. At the end, they reported a 68 percent reduction in severity—a result comparable to steroid creams, with fewer risks.

“We don’t know the full mechanism of action, but we do know that it demonstrates anti-inflammatory benefits, so it seems to inhibit the inflammation and the itching,” reports Dr. Browning. Data also suggest the oil can inhibit pro-inflammatory pathways like the enzyme PDE4, thought to play a role in eczema and other inflammatory skin conditions, and has antiseptic properties that prevent and treat secondary infections. “People with eczema often have staph or strep on their skin, and it helps to remove that—without requiring the use of oral antibiotics,” he says. “A lot of patients are looking for a natural-based product—they’re really drawn to using an organic extract as opposed to a chemical manufactured in a laboratory.” Currently, Quintis’ oil is part of five clinical trials, including a larger phase 2 clinical trial for eczema and other skin conditions.

What Led to Bankruptcy?

As recently as February 2017, Bloomberg Business News painted a rosy future for Quintis in its article, “This Sandalwood Plantation Is About to Make Its Owners a Lot of Money.” They wrote: “The trees are maturing just as prices soar amid a production shortfall from the biggest producer in India and rising demand from China. A kilogram of Indian sandalwood oil now sells for about $3,000, and prices are rising by at least 20 to 25 percent a year, according to the South India Sandalwood Products Dealers & Exporters Association. Global demand for sandalwood is set to gain five-fold by 2025. The company plans to increase output 30-fold to 10,000 tons of timber a year.”

Bloomberg’s report quotes Frank Wilson, the largest shareholder and managing director of Quintis speaking optimistically about the future. But just a month later, Wilson quit the company to join a competitor looking to take over Quintis—an attempt that ultimately failed. The same week Wilson left Quintis, Glaucus Research Group, an American short-seller (investors who bet a company’s stock is going to fall) published a savage report on Quintis likening it to a Ponzi scheme. They said the company had borrowed large sums of money over the years and continued to borrow to repay earlier investors, as income from the trees was nearly nil.

Quintis stock plummeted and trading was halted on May 12. Also in May, Quintis’ board was forced to reveal that the dermatology company Galderma, a subsidiary of Nestlé and expected to be a major customer, had not bought any oil from them since 2015. Similarly, a Chinese buyer, Shanghai Richer Link, had not ordered any wood for 2017.

On January, 7 2018, shareholders called a meeting to express lack of confidence in the present board of directors. The company’s financial obligations looked impossible to meet. On January 20th, according to the Australian Financial Review, Quintis declared bankruptcy, and “The company-appointed administrators and shareholders stand to see nothing in return.” On January 22, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission announced an investigation.

Out of all of this, however, did come voices of hope for the future, one from Teague Czislowski of the Sandalwood Growers Co-op. He estimates the planation will ultimately yield returns of $100,000/acre. A market report cited by AFR predicted the Chinese market alone for Santalum album will grow 18 to 34 percent per year and reach 7,400 metric tons by 2025. Local Kununurra farmer Robert Boshammer is quoted in a January 7th Reuters report as saying, “Sandalwood has a bright future in the region no matter what.”

India’s Sandalwood Scene

As Australia’s vast plantations falter, can India moderate its overzealous regulations and contain black market corruption to make a comeback?

BY RAJIV MALIK, DELHI

SANDALWOOD HAS BEEN AN INTEGRAL part of India’s and Hinduism’s religious and cultural moorings from times immemorial. Each newborn child is welcomed by applying a sandalwood tilak on the forehead. Sandalwood paste is presented as a sacrament for every Hindu ritual, and the final funeral pyre has at least some sandalwood pieces or powder placed on it. Scripture extols its qualities.

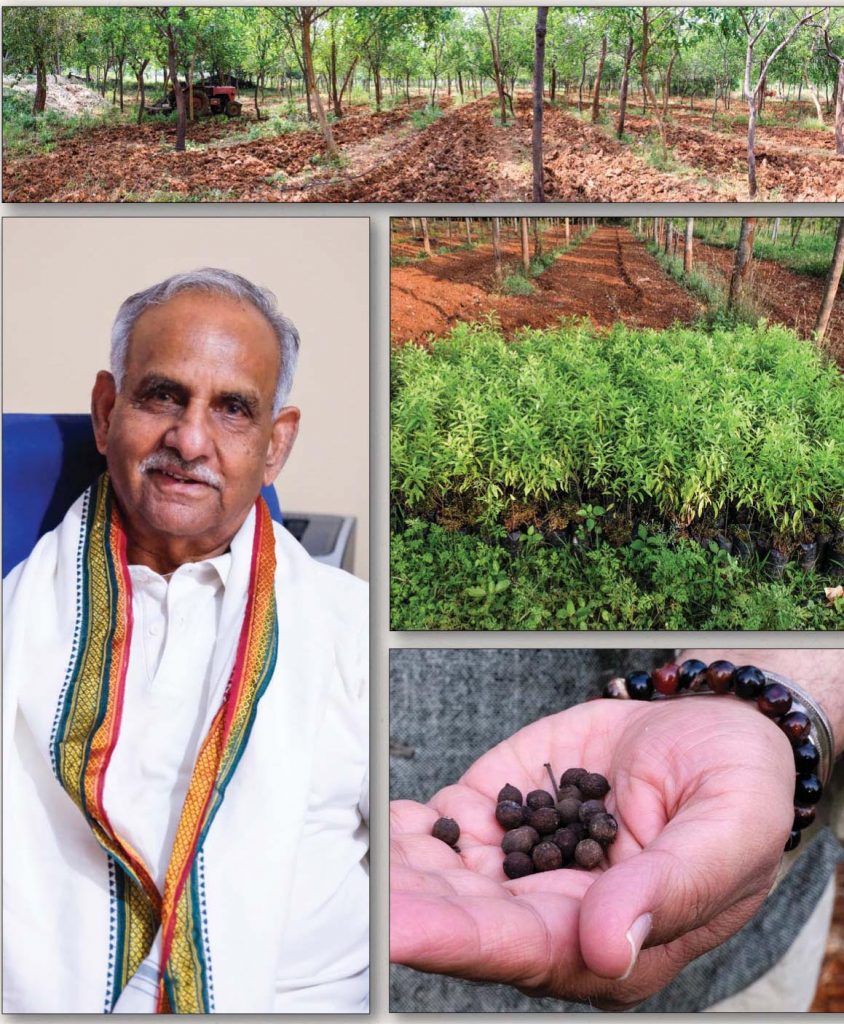

Sandalwood is—or was—most common in the south of India, in what is now Karnataka State, an area known in ancient times as Gandhada Gudi, the mountain or temple of sandalwood. This one state alone contains more than half of India’s sandalwood growing regions. The adjoining states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala also are traditional areas of sandalwood supply; but Karnataka, specifically Bengaluru, is today the center of the sandalwood trade. And it is in Bengaluru that HINDUISM TODAY sought out Dr. H. S. Anantha Padmanabha, the acknowledged world expert in sandalwood. Now retired, Dr. Padmanabha devoted his entire professional life, starting in 1954, to research on sandalwood.

His living room, where I interviewed him over two days, is a virtual sandalwood museum, displaying wood samples, oils and various other products. He has traveled to over one hundred countries promoting and helping sandalwood projects by sharing his wealth of knowledge through participation in seminars and symposiums. Two of our Kauai staff met him at a 2012 conference in Hawaii. He has published several books on the topic and over 150 scientific papers. He makes himself available to anyone who wants help with growing sandalwood, with a special focus on creating viable sandalwood plantations in India.

Karnataka, he bluntly told us, was once number one in sandalwood cultivation but now lags behind Tamil Nadu and Kerala. He told us of the main factors involved. There is a high level of corruption in the forestry department; the government’s policies are lopsided and directionless; and sandalwood mafia and poachers have looted, plundered and smuggled Karnataka’s sandalwood reserves.

Dr. Padmanabha related that at a recent auction held at Shivamogga, central Kerala, sandalwood was sold by the ton for about $196/kilogram, including taxes running over 30%. This, he said, is the prevailing rate, and it can only continue going up. The Australians, whose labor rates are much higher than India’s—and who harvest their trees at just 15 years of age, are selling sandalwood for $283/kilo, and the oil for $4,718/kilo. India’s trees yield a higher-quality oil, since they are not harvested until age 30. In spite of the quality difference, India’s sandalwood oil sells for just $2,830/kilo. At the retail level, one can buy pure sandalwood billets at Cauvery Emporium in Bengaluru for $422/kilo.

(Clockwise from above) Sandalwood Ganesha on display at Cauvery Emporium, Bengaluru; Namdhari Seeds plantation; seedlings ready to plant; seeds from the trees—they’re edible and a favorite with birds; Dr. Anantha Padmanabha, world’s foremost expert on sandalwood

There is also fake sandalwood, created by sprinkling synthetic sandalwood oil on wood that looks like sandalwood. Padmanabha can tell if the wood is real, and even estimate the oil content, by chewing on a piece—but that requires an educated tongue. The non-expert is best off buying at reputed sellers, such as Karnataka Soaps and Detergents Limited. There has been research in both Australia and Kolkata to artificially duplicate genuine sandalwood oil. This has met with some success, but the such oil would cost ten times as much as natural oil.

Sandalwood oil has long been used in Ayurveda to treat skin conditions, and other pharmaceutical applications are being explored in India. Currently, major uses of the oil in India include soaps, mouth fresheners (gukta or pan) in very small quantities, and chyawanprash, an Ayurvedic preparation of amla fruit and many other ingredients. One of Dr. Padmanabha’s projects is an advisor to a 250-acre sandalwood plantation for Dabur India, a major producer of chyawanprash.

Padmanabha told us sandalwood trees have been state property since the time of Tipu Sultan in the 17th century. Only recently has this been changed in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. In these states, trees can now be the property of the land owner. But still, each tree has to be registered and can only be cut and sold at auction by the forestry department. None of these restrictions exist for the rest of India. Recently the Central Government in Delhi has ordered the states to change their laws again so that any tree grown as an agricultural product (as opposed to wild trees) is not only the property of the owner, but may be sold by him as agricultural produce. Those laws have yet to come into force.

There are sixteen species of sandalwood worldwide, according to Padmanabha. The Indian variety, Santalum album, is the most productive and has the best quality wood and oil. Highly adaptable, the species grows in many areas of Southeast Asia and other places, including Africa. Some claim it is indigenous to Indonesia, but Padmanabha believes that its home is India, due to the long historical record.

The trees require a host plant throughout their life, but can adapt to many different hosts—some 400 have been identified. The tree absorbs nutrients from its host very selectively, taking in only those it needs and rejecting what might be harmful. Dr. Padmanabha’s research has identified about 30 short- and long-term host plants most suitable for conditions in India. Several of these have commercial value themselves, including the drumstick tree (moringa), amla, betel nut, chikoo, ginger, turmeric and pomegranate. Plantations can also be intercropped with onions, garlic and potatoes, making use of the space between trees for cash crops. As sandalwood must grow at least 15 years before harvest, such secondary crops can pay the farmer’s yearly bills. Sandalwood trees also benefit from the attention paid while the farmer is caring for the other crops in the plantation. Padmanabha said the Australians, faced with high labor costs, did not consider it profitable to plant cash crops between their trees, which then forced them to finance the entire project for at least 15 years. In India, such intercropping can be done profitably, a major advantage avoiding a cash drain to the farmer.

India’s official production is 250 tons a year, explained Padmanabha, but eight times that much passes through the black market at a price of about $160/kilo, with illicit oil selling for $283/liter. This is genuine sandalwood, he points out, but the black market has no overhead and pays no taxes. The dealers pay the tree cutters just $15/kilo. Smugglers actually have more control over the sandalwood trade than the government. Because of smuggling, India’s legitimate commercial sandalwood trade has nearly vanished.

Sandalwood in the Perfume Industry

SANDALWOOD HAS BEEN ENJOYED FOR ITS AROMATIC QUALITIES for over four thousand years. Due to its unique fragrance, sandalwood remains prevalent in perfumery to this day. Sandalwood is especially prized for its distinctively soft, warm, smooth and creamy scent. It has two unique properties: it can blend easily with any natural essential oil, even those with a much stronger fragrance such as jasmine, lavender and peppermint; and it has a high boiling point of some 300°C, which means it is very long-lasting in perfume. Synthetic sandalwood oils are usually alcohol based. Even if they initially smell similar, they rapidly evaporate and disappear. They also do not mix well with other essential oils.

Sandalwood oil is considered in the perfume industry as a neutral oil, suitable for perfumes for men or women. It is used in Indian perfumes, attar, where its presence is easily recognizable. Western manufacturers use it as a featured scent, or with stealth to create a more subtle interaction of complementary scents. Quintis company refuses to reveal any of the perfume manufacturers who purchase their sandalwood oil.

CASWELL MASSEY

Prized scent: (left) Indian attar made with sandalwood oil ($11 for 1/2 ounce); (right) sandalwood cologne ($44/3 ounces) by America’s oldest perfume maker, Caswell Massey, founded in 1752

“Once I was interviewed by a media channel on sandalwood, and immediately thereafter the same channel interviewed a famous sandalwood smuggler by phone,” recounts Padmanabha. “He offered to deliver any quantity of sandalwood to any place. If such people can talk openly with a TV channel, why cannot the government catch them? All this is happening because they are working hand in glove with the forestry department people. I have witnessed this myself.”

Two issues must be solved, he says: the corruption in the forestry department and the theft of trees by the sandalwood mafia. The first is a government issue; the second, he believes, can be prevented through technology, such as microchipping the trees, and by proper investment in security by the farmers once the trees are mature enough to be vulnerable to theft. A 15-year-old tree is worth one lakh rupees ($1,600). By spending just a small percentage on security, the farmer can realize the full value of his efforts.

India’s Top Sandalwood Company

Enlisting Dr. Padmanabha’s help with this report brought the boon of his high-level contacts within every near-by business dealing in sandalwood. He instantly arranged for us to meet Hari Kumar Jha, managing director of Karnataka Soaps and Detergents Limited, the largest company in the world dealing in sandalwood products. We also secured appointments with three leading plantation owners, all of whom freely shared their experiences and opinions with us.

KSDL, founded in 1916 under the Maharaja of Mysore, maintains a forty-acre campus in the heart of Bengaluru. To enter this place is to enter another world. The scent of pure sandalwood is overwhelming, energizing—intoxicating even. It pervades the modest office where we met with Jha and is even more potent in the building where their famous Mysore sandal soaps are manufactured and packaged. Each bar contains two percent sandalwood oil. Everything in the factory, save the final packaging is completely automated. Yearly the company produces 13,000 metric tons of soap worth us$71 million.

Their soap is popular with the older generations, Jha stated, but the youth prefer the more heavily advertised and cheaper multinational soap brands. He hopes they will eventually switch as they come to realize sandalwood’s benefits for their skin health.

Jha told us the company now deals in sandalwood oil in “very reduced quantities than we used to.” Previously they could count on a certain allotment of the wood production, but now they must compete with others at the government auctions. Supply was not an issue until 1964, when the Karnataka Forest Act came into effect with its many restrictions. Only in 2003, with the threat that sandalwood might actually go extinct, did the government take action.

Government restraints on the industry still exist. As an example, KSDL is the only company in India licensed and permitted to extract sandalwood oil. These constraints are a legacy of India’s “license raj,” the attempt instituted under Nehru to control the economy by requiring companies to have a government license before manufacturing and selling just about any product—with the government even setting the selling price. Reform of the license system was undertaken in earnest in 1991.

The government appears to have realized that such laws have been a major obstacle for the industry. Jha is encouraged by recent signs that the rules and regulations still throttling the industry in Karnataka will be relaxed. In anticipation, KSDL has entered into agreements with thousands of 0ne- and two-acre farmers to help them grow sandalwood, providing seedlings and supplying advice on growing methods.

Meeting the Cultivators

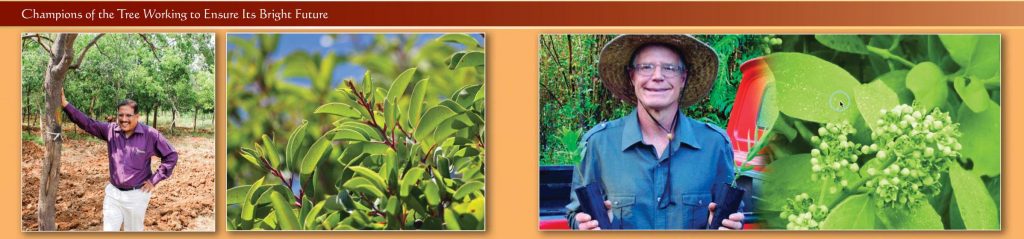

We were able to visit three sizeable sandalwood plantations, each within a 200-km radius around Bengaluru. None were anywhere near the scale of the Australian plantations. The first, in Tumkur district, is run by Namdhari Seeds, one of the largest vegetable seed companies in India. It is owned by members of the Namdhari religious sect, a branch of Sikhism. They started their plantation under Dr. Padmanabha’s guidance in 2002 and now have 7,000 trees growing on 40 acres of land.

Some of the trees are now harvestable. They would be much more valuable in another decade; but the manager, Ramesh, explains that due to fears of theft, they are harvesting now rather than wait for the sandalwood mafia to steal the trees in the dead of night. He says this is the biggest problem cultivators face, and the government must enact and enforce far more stern laws against smugglers. If that were done, he could confidently plant more acreage. He also recommends that the license permit system be liberalized. It is presently so cumbersome it discourages people from getting into the business. They must have impeccable proof of land ownership and must register every single tree with the government.

Wood and Soap: (upper left) raw billets selling for $422/kilo are Cauvery Emporium’s most popular sandalwood item; (directly below) KSDL’s popular sandalwood soaps—the one at right, with its fancy packaging, is aimed at the current generation

On another day we visited the farms of cousins Chinalu in Chamraj Nagar District and Nanje Gowda in Mandya Taluk. Chinnalu’s farm has 50 acres in sandalwood with 10,000 trees, and Gowda has 7,000 trees on 25 acres. Gowda carefully selects income-producing host trees and otherwise makes good use of the open land between trees for cash crops. The initial host is red gram, or pigeon pea, followed by gliricidia or stick plant. This nitrogen-fixing plant is used as cattle fodder when young and fence posts when more mature. A third host is Wrightia tinctoria, a type of oleander that produces an indigo-like dye. Its fine, white wood is used for carving, and it also has a number of uses in Ayurvedic medicine. Other cash crops used as hosts at different stages of growth include black pepper vine, silver oak and drumstick trees. All were implemented under the advice of Padmanabha and are still being evaluated by the farmers.

UNKNOWN

SHUTTERSTOCK

SUNDER RAJ

The various uses: (counter-clockwise from below) Sandalwood sepulcher of the late King Bhumibol of Thailand, in which he was cremated; Gandhi’s funeral pyre was made with 1,200 pounds of sandalwood and 320 pounds of ghee—today a token billet is commonly used; parrot carved inside a cage; incense; carver Sumitra at work

As their trees are less than ten years old, Chinalu and Gowda do not yet face the problem of theft, but they share exactly the same concerns as Ramesh of Namdhari Seeds.

Carvers and Sellers

Carvers in this area obtain wood legally only from the Karnataka Handicraft Board. At each government auction, ten percent of the wood—usually the larger pieces—is sold for carving at a subsidized rate. The artisans are mainly in Mysore and Shivamogga areas. Originally they were mostly of the Gudikar jati, but others have entered the craft and now Gudikars are perhaps 30 percent of the total.

Finished carvings must be sold back to the Board. Padmanabha says the carvers get only a small part of the profit, with most going to the Board. The situation is the same in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, but other states allow the free purchase and sale of sandalwood as long as it is grown in their state. Depending on the piece, 30 to 70 percent of the value of a carving is in the cost of the wood.

Padmanabha estimates only 20 percent of the carvings in Karnataka come from legal sources; the remaining 80 percent do not and are sold through shops opened by the carvers themselves. The difficulty in getting a legal supply has caused many artisans to switch to stone carving, especially in Shivamogga.

Two of the top names in carving in Bengaluru are Vaijinath G. Ganeshpur and his son Vishwanath V. Ganeshpur. They manage an NGO, Karakushala Kaigarika Sahakar Sangh Ltd, which employs 400 carvers, and maintain the KKSS showroom in central Bengaluru. Before coming to Karnataka, I had visited the top emporiums selling sandalwood sculptures in Delhi, but none came anywhere near the quality and price of what this company offers.

The most expensive piece we found in Delhi was 40 lakh rupees (US$63,000). Here a spectacular six-foot-tall sculpture of Radha and Krishna’s ras leela in Braj (photo page 32) which is solid sandalwood and took four artisans two years to complete, goes for one crore rupees ($157,000)! The economic reality of sandalwood figures very much in this pricing. With the wood accruing in value twenty to thirty percent a year, the company can patiently wait for an art lover willing to shell out a high price for such unique pieces of art.

KKSS’s Vaijinath is frustrated by the red tape surrounding sandalwood. He must keep track of every ounce of wood bought from the auction, and he is subject to government audits. He said he has often wanted to quit the business, but has not done so because he feels responsible for the 400 artisans and wood carvers working for their NGO. He is concerned for the future, however. Few of the carvers’ children are taking up the trade, finding better jobs elsewhere. “At one point of time,” stated Vaijinath, “there were 1,500 high-level fine art carvers in this industry. Now the number has shrunk to less than around 150.” He estimates KKSS has trained six to seven thousand artisans over the years.

Son Vishwanath told us that besides dealing in high-value items, they also make small carvings of Hindu Gods, key rings, incense and many other products which cost just a few hundred rupees or less. The business is lucrative, as there is no waste. Every bit is utilized in products such as incense sticks, which are in good and regular demand.

KKSS supplies Cauvery Emporium with high-value carvings and incense alike. The state-run shop, considered the premier source for sandalwood in all of India, carries a huge range of products. Its manager, Mainak Mandal, takes special interest in selling expensive sandalwood Deities and shrines to rich customers building new homes.

Until around 2000, KKSS supplied hundreds of carvings a month to Japan, Taiwan and China. But as the wood became dramatically more costly, this business dropped off.

Equal in scale to KKSS is the Shilpa Trust, with 400 carvers, run by M. Bhupathy. He and his brother, M. Ramamurthy, who runs Wood Mantra, are sixth-generation award-winning carvers. Both are happy their sons have joined them in the business. They are of the Viswakarma community, which also includes temple carvers and architects. They shared the same complaints about government policy and poaching, and also said the government emporiums are not properly promoting the woodcarving art, but just looking after their business interests. Both brothers run training schools for young artisans, but, like KKSS, do not find many youth interested in the profession, even though they pay students’ expenses as well as a stipend for the entire three years of training.

Whither India’s Sandalwood?

“We see the future of sandalwood as bright,” stated Padmanabha. “Once it was listed as an endangered species, and it is still listed as ‘under threat.’ I want this removed and sandalwood to be freely available in the world. Here in India, if farmers grow sandalwood along with cash crops, they will stop committing suicide due to financial problems. I am happy to share all the knowledge I have with any farmer, big or small.”

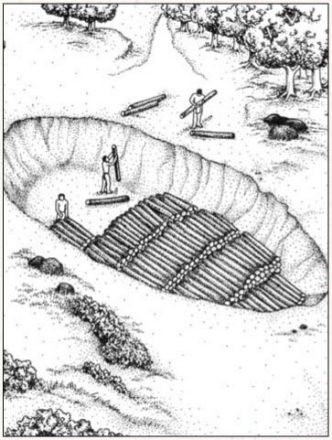

Past, present and future: (clockwise from above); KKSS’s Vishwanath V. Ganeshpur with the $157,000 carving of Radha and Krishna; Hawaiians pack a mountain pit the size of a ship’s cargo hold with sandalwood before hauling it down to the docks; Mark Hanson works to preserve Hawaii’s native sandalwood species; leaves and buds of the sandalwood tree; C.V. Ramesh, manager of Namdhari Seeds

Sandalwood, it could be said, has been too treasured for its own good. Modern transportation has allowed its easy shipment from places of plenty to the rest of the world, fueling a demand which drove the tree to near extinction. Growing abundantly in sparsely inhabited forests, it was easy pickings for those beyond the law. Today, organized, secured plantations provide a viable path forward for one of nature’s most fragrant creations. India’s government must take strong measures to vigorously protect the trees against theft and corruption and to eliminate the vestiges of the license raj inhibiting production. Then the sandalwood which has served the Hindu community well for thousands of years will do so for the next thousand.

Hawaii’s Piteous

Sandalwood Tale

It took just 40 years to exhaust the originally abundant native species

KAUAI, ISLAND HOME OF HINDUISM TODAY MAGAZINE, WAS once, briefly, a major source of sandalwood. The Hawaiian island chain is home to six of the world’s 18+ species. The Hawaiians knew the tree as iliahi and used it for scenting kapa cloth and as a medicine. Hawaiian species, such as Santalam paniculatum, are not as large or straight as their Indian cousin, and the wood is less desireable. Until the early 18th century, the remote islanders were unaware of its great value in the global market, especially in China.

However, when King Kamehameha I learned of its high demand—caused then, as now, by low supply from India—he ordered the entire able-bodied population to harvest the trees, everyone from chiefs to common people. Workers would uproot the trees to get at the oil-rich stumps, saw up the logs and transport them on their backs, down the mountains through challenging terrain. Pits were dug to the same dimensions as a cargo ship’s hull (see right) to measure a shipload. Wood was stacked in the pit until full. Then the logs were transported to the beaches. The conditions were unpleasant for these workers, who were already plagued by diseases brought by the Europeans. Even worse, the king’s greed for sandalwood resulted in reduced agricultural production of food, and famine ensued. Kamehameha finally placed a kapu (ban) on the harvest of iliahi in order to bring island life back into balance.

In 1819 he died and his son Liholiho took the throne as Kamehameha II. Shortly there after, he abolished the kapu system, sending the iliahi harvest back into overdrive. By 1821 the kingdom of Hawaii was $300,000 in debt for foreign goods, ships and liquor. The abuse of credit was fueled on both sides. The Hawaiian chiefs indulged in lavish commodities, while foreign traders, eager for the sandalwood, pushed the credit system on the islanders. As the iliahi got harder to find, workers resorted to burning forests to locate the trees by their powerful smell. The older trees survived the fires—only to be cut down—but the younger saplings were eradicated in the process.

By the time Kamehameha II passed away in 1824, the next heir to the throne inherited a debt of $500,000 owed to American traders—a fortune in those days. In 1827 the new king enacted Hawaii’s first written law, the sandalwood tax, to pay this debt. This tax required every man to deliver 70 pounds of sandalwood, or pay four Spanish dollars, to the district governor each year. Women of age 13 and older were required to weave a 12 foot by 6 foot mat, or to pay one Spanish dollar. By 1830, the forests were exhausted, and Hawaii’s sandalwood trade ended.

Today one can find a tree on the Hawaiian Islands only with great difficulty. A few commercial-scale efforts are being made, but the primary interest is in simply preserving the native varieties. In fact, planting of anything other than indigenous species—especially India’s Santalum album—is discouraged, as unwanted hybrids would result.

Everywhere sandalwood is found, its history has been filled with a reverence for the tree’s qualities and insatiable greed for the profits it can bring. Hawaii, the Aloha State, has been no exception.