There are many ways to conceptualize 240 million people: 3.2% of the world’s population or 72% of the US; 200 times the population of Paris; enough to be the fifth largest country in the world. On January 15th alone, fourteen million—some say 20 million—joined the Royal Bath at the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and celestial Saraswati Rivers adjacent to the host city of Prayagraj (population a mere 1.5 million). It was the largest gathering of humans for one event in history. In attendance were India’s foremost religious leaders, hundreds of thousands of sadhus and millions of Hindus, from India’s great cities to her smallest villages. They were there to take a holy dip in the sacred rivers, have darshan of the saints and enjoy each other’s company in grand celebration. Come with us as we describe the event and our encounters there.

BY RAJIV MALIK, FROM PRAYAGRAJ

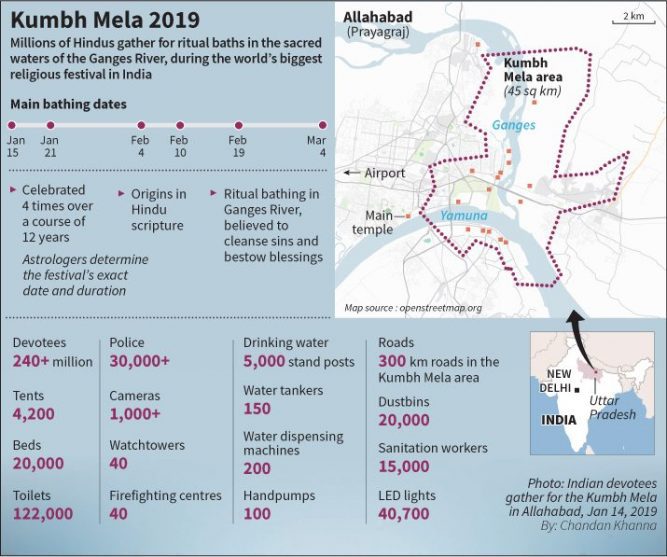

THE 2019 KUMBH MELA WAS AN EXtraordinary event, far surpassing any in history. Credit for the scale and the superb organization must go to the host state government of Uttar Pradesh—itself led by a sadhu, Yogi Adityanath—and to India’s central government for its strong support. One can get a sense of professionalism applied by visiting the superb Kumbh website (in Hindi and English) at kumbh.gov.in/en. This website and the smart use of social media were major factors in promoting the event, not only in India but worldwide. The festival commenced on Makar Sankranti, January 15, 2019, and concluded on the holy day of Mahasivaratri, March 4.

According to UP’s finance minister, Rajesh Agarwal, the government allocated us$588 million for the festival, compared with $182 million for the 2013 event. The contrast is even greater when one considers the 2013 celebration was a “maha mela,” one occurring every 12 years, while this year’s Kumbh was the in-between, six-year event, called ardha (half) mela, which is usually on a smaller scale. One can only imagine what the 2025 maha Kumbh here will be like!

The Confederation of Indian Industry, a nation-wide NGO founded in 1895, estimated the festival created 600,000 jobs and generated business worth $16.8 billion. Fortune India magazine called that an “astounding return” on the government’s investment of a half billion dollars. The Kumbh has been a special boon for Uttar Pradesh, one of India’s poorest states, with 30 percent of the people below the poverty line.

Grasping the Kumbh’s Extent

The event’s infrastructure development extended well beyond the official area. Highways leading into Prayagraj were improved and parking areas were created for 500,000 vehicles. Five hundred shuttle buses and thousands of auto rickshaws, running on compressed natural gas, were mobilized to ferry pilgrims to the grounds. Both the airport and railway station were upgraded. The huge influx was controlled by police and paramilitary forces from UP and adjacent states.

The festival area was immense—13 miles from north to south and half that on average east to west—17 square miles of land in all, double that of 2013. Within this area, 186 miles of roads were built, mostly of large steel plates laid on the sand, along with 22 pontoon bridges to reach the far side of the Ganga. Vehicles were allowed inside the area on normal days but were heavily restricted during the main bathing days.

The numbers describing the facility are phenomenal: 122,000 toilets, 15,000 sanitation workers, 20,000 trash bins, 40,700 LED street lights, 2,000 electronic display signs, 2,000 volunteers just to clean the river banks, 40 fire-fighting posts, 40 police stations, 40 watch towers, 1,000 surveillance cameras and a loudspeaker announcement system that reached every corner of the area. All of this was overseen from a high-tech command and control center to manage safety and security (see sidebar on page 22). Last but not least were a dozen hugely popular selfie points where pilgrims could take photos with the Kumbh Mela logo and a grand scene behind them.

Implementing someone’s brilliant idea, tea counters were set up next to the waste bins. Deposit waste in the bin and you get a free cup of tea! Such bins were everywhere and helped accomplish an unprecedented level of cleanliness. Savita Gupta, of Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, here with her son Shubham, 22, reported, “Such cleanliness was never seen in a Kumbh in the past. We heard so much about the good arrangements through the media, and it was absolutely true. The event is even better organized than what we’ve seen on TV. With so many police, we feel quite safe and secure. They are so cooperative and polite.”

Some of the 4,200 top-level accommodations here cost as much per night as a five-star Delhi hotel. We encountered pilgrims who apparently thought their expensive thin tent would have hotel-like accoutrements, such as hot water (no), secure locks (no) and a leak-proof roof (not that either). Experienced pilgrims brought their own coffee pots to have at least some hot water.

According to the organizers, there was a capacity of 20,000 beds within the grounds, but practically speaking, people slept wherever they could. This presented a difficult challenge during the cold and rainy first few weeks of the 48-day event.

The huge Ganga Pandal for cultural, spiritual and official events had a capacity of 10,000. Smaller halls spread through the grounds could hold a few thousand apiece. More than 600 cultural programs featured over 2,000 artists from all over India. These included musical performances, classical and traditional dance and more. At night the halls served as safe places to sleep.

The entire city of Prayagraj was part of the festivities. Buildings, pillars and any surface facing a street became murals to highlight the religious, historical and cultural aspects of the world-renowned fair. Highly decorated gates on specific themes graced the 25 main entrances to the grounds. Tours were set up to bring people to the important temples and places of the city.

A key initiative was the Kumbh Sevamitra, a program fielding 5,000 volunteers per day, increasing to 8,000 on peak days. These volunteers proved to be the face and backbone of the event. They offered their services in the areas of crowd and traffic control, especially near the bathing ghats. They served as tour guides for pilgrims and helped reporters at the huge government-run media center. In addition, they worked at the always-busy lost-and-found stations.

Hundreds of photographers from India and all over the world jammed the elevated stands erected just for them. Security was tight, with commandos, local police on foot and horseback, paramilitary forces, and units of India’s Rapid Action Force specially trained and deputed to deal with crowd control and potential riots or stampedes.

The Immensity of the Kumbh

The Pilgrim’s Experience

The two biggest attractions for pilgrims were taking a holy bath in Ganga and seeking the darshan of sadhus and saints who were there in the hundreds of thousands, staying at the camps of their respective akharas, monastic orders. Meeting and interviewing those saints was a main objective of HINDUISM TODAY’S reporting for this event.

Ashwin Johar, 45, of Delhi summarized the experience for many: “Here at one place hundreds of thousands of people are chanting the name of God at one time. It seems that the whole universe is reverberating with the holy songs. This is something out of this world. The kind of arrangements made for this Kumbh are unimaginable and unprecedented.”

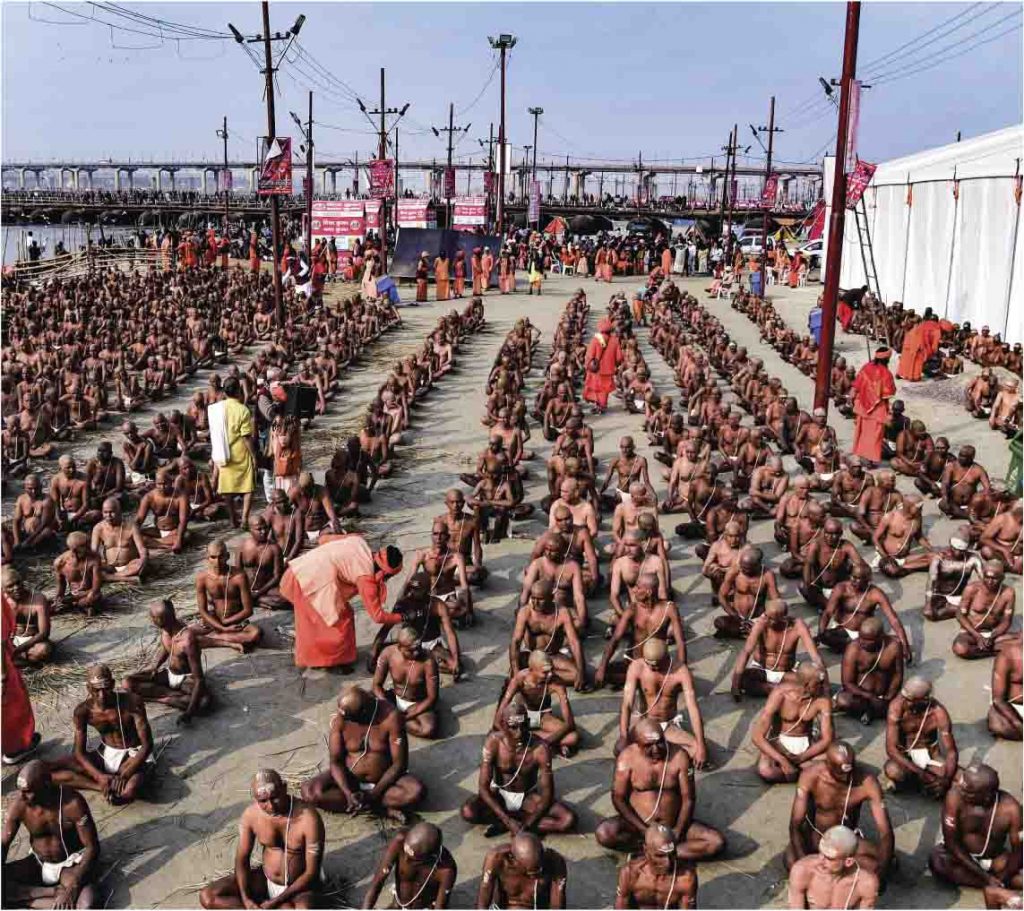

At its peak on the auspicious days of the Royal Baths (Shahi Snan), tens of millions of pilgrims followed along as the various akharas of saints took their baths, starting early in the morning following a traditional order of seniority. All proceeded toward the river in a mood of meditation and as they approached the water danced with joy, shouting “Har Har Gange” and “Har Har Mahadeva” before rushing into the icy water. This is the one time ordinary devotees get a glimpse of the renunciate naga sadhus, here in huge numbers and unclothed except for garlands around their necks. For many pilgrims, darshan of these holy men and women is as great a blessing as the river bath.

Most of the pilgrims are from the rural areas, many coming straight from the bus stands with luggage on their heads. Dressed in colorful dhoti kurtas and saris, they stand in contrast to the urbanites in their jeans, trousers and t-shirts. Whether urban or rural, all move silently toward the river.

After immersion in the icy water, most can be seen performing puja on the river banks, some with the help of priests. In a few places, even small homas, fire ceremonies, are performed. Many arrive and leave on the same day; but before departing the grounds, pilgrims give donations to the beggars and poor people lined up to receive them.

A special class of pilgrims are the kalpvasis, who come here to live for an entire month. One of these, Govind Ram Agarwal, is here with his wife, Santosh. “I will be wearing just one dhoti, and both of us will have food only once a day. Whatever the climatic condition, we have to have our holy bath every day. We spend our time attending Bhagwat Kathas and visiting the different camps of saints.”

Another type of devotee we encountered here can’t really be called pilgrims, for they live in Prayagraj itself. Arun Kumar Pandey, 65, belongs to a group of locals who come every single day, year around, to bathe at the Sangam. He pointed out that the Kumbh area was so large that the kalpvasis and the elderly had trouble negotiating the long distances to reach the confluence area.

The Transient Camps

Each of the major akharas has its own flag for their main Deity flying high above a temporary temple, where regularly scheduled worship is open to all devotees. The overall mood is one of a festival, with statues and pictures of Gods and Goddesses placed everywhere.

There are thousands of such camps, big and small, where pilgrims can meet and talk with the saints and participate in havan (fire worship), katha (storytelling presentations), lectures and bhajan, which take place all day and into the night. One small camp, Maibada, “home of the mothers,” is for women saints of the Juna Akhara. There are also individual tents with ash-smeared sadhus sitting around their fire pits, performing puja or tapas. If the sadhus appear occupied, pilgrims will just silently take their darshan (blessings) from a distance. One can also sit patiently and wait for an audience.

It is customary in all camps at all times of the day for the saints to offer tea and snacks to the pilgrims. The major camps provide bhandaras, or community meals, three times a day, which are a mainstay for kitchenless devotees. At many places there are arrangements for serving the sadhus separately.

The most magnificent and talked-about camp here was that of Swami Avdheshanand, head of Juna Akhara, which housed thousands of saints and devotees. Despite its nonpermanence, the main tent of the meticulously landscaped camp looked like a huge palace, tastefully decorated and furnished. Another hall held several thousand devotees at a time for kathas, cultural programs and talks. Though far from the main Sangam area, it was a big attraction for hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. It is believed this one camp cost around two million dollars.

Pilgrims also flocked to the camp of Swami Karshney Gurusharanananda Ji Maharaj, another eminent saint of India. Here, too, was a prodigious hall where cultural programs went on continually.

Policing the Kumbh

THERE ARE TWO MAJOR THREATS TO AN EVENT OF THIS KIND: A TERrorist attack and a stampede. In the worst-case scenario, the former causes the latter. Involved in security were police from 25 states, plus all three wings of India’s armed forces—army, navy and airforce. The navy provided water rescue training and the air force supplied ambulances and fire-fighting equipment and personnel.

According to Purnendu Singh, additional superintendent of police, the protection against terrorism involved heavy deployment of both police and armed forces on all main roads leading to the Kumbh, beginning 150 kilometers out and continuing inward through five levels of security, with checkpoints and random searches. Anti-sabotage and bomb detection teams conducted daily sweeps, while 460 closed-circuit cameras monitored the Kumbh area. Stampedes were successfully averted by paying careful attention to the flow of pilgrims, with designated entry and exit routes—avoiding the two-way traffic which in the past has led to disasters.

Theft was also a major problem, though obviously a different level of concern than terrorist attacks or stampedes. According to Singh, there are entire communities known for their criminal activity at the Kumbh. One such is the Burwar tribe from Gonda. “They do not come as individuals,” he said. “The complete village comes—men, women and children—with only theft in mind, no religious purpose. They are very organized and immediately have members depart the area with the stolen jewelry or cash, so it is very tough to recover anything. But overall, it is difficult to commit a crime in the area due to the heavy deployment of all kinds of forces here.”

Mass Bathing

Seeing the Real Mela

BY DHANANJAY Joshi

THE KUMBH I HAD HEARD ABOUT WAS very different from the Kumbh I actually saw. The Kumbh I had heard of was supposed to be stiflingly crowded, stinkingly filthy, starkly down-market and swarming with fake, unwashed sadhus. It was so unspeakable that only Indian government TV channels reported it. “Civil society” was dismissive and focused only on ridiculing the name change from Allahabad to Prayagraj. Instead, what I saw at Prayagraj was the event UNESCO calls “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.”

It took us 78 man-hours to soak in the divinity spread over 17 square miles—just a bit more than all of New Delhi. The Kumbh is sensory overload. Rising above the cacophony of sounds and sights, I saw a throbbing, vibrant mass of consciousness living the timeless ritual just as their ancestors had for eons before them. This Kumbh was about making the humblest pilgrim connect with their self, making the humblest pilgrim proud of their shared heritage. It was about giving the forgiving pilgrim a clean and safe environment. My immersion at the Triveni Sangam was an experience that connected me to every individual in the world. The oneness with the thousands around me was calming.

I saw the bogey of hygiene busted. Two thousand health workers took responsibility for their tasks with missionary zeal. Decentralized teams toiled round the clock in geographically dispersed teams to keep the 122,000 toilets squeaky clean. Tankers daily ferried sewage to the nearest treatment plant. Rodents and cockroaches were absent entirely. Everyone did their bit to be eco-friendly.

The flower sellers at the ghats had radically updated their flower baskets from plastic to handmade paper boats. These were laden with organically grown, locally sourced rose petals and soluble mud lamps with beeswax and a cotton wick. At the Triveni sangam, this age-old biodegradable offering was bestowed on the Ganga. Clear water from the Ganga was carried home by the faithful in plastic containers.

From the anchored pontoons in the middle of the sangam, the aged, the young, the differently-abled and the enthusiastic descended onto special bathing platforms under the watchful eyes of life-guards on their bobbing life rafts. Every single pilgrim was wearing a life jacket—the local boatmen ensured it! Lips sent out silent prayers, tears streamed down faces, and some shivered in the cold waters as they energized themselves with loud prayer. Hundreds of folded hands reached out to the heavens, and one pair was mine.

In the Kumbh I had heard about, sordid tales told of swirling unwashed masses jostling against each other. They warned that women were not safe and to beware of inappropriate touches. The Kumbh that I saw was full of families—men, women, children and grandparents with head-loads of their belongings, caring for each other, walking purposefully with devotion in their eyes. I roamed around at night, under the swathes of the 40,000 LED lights that dotted the riverbanks, and I felt safer here than in any city of the world. The voices of police personnel went hoarse as they patiently gave directions and repeated instructions innumerably. These handpicked teetotallers, non-smokers and trained officers, were an example of a sensitized police force. The Kumbh I saw had 22 pontoon bridges, each unidirectional and crowd controlled to prevent a stampede.

The Kumbh I had heard about was a religious gathering of Hindus. Inside would be Hindu zealots, fake babas giving fanatic talks, persistent priests pestering for puja. In the Kumbh that I saw, small crowds gathered in the innumerable akharas to listen to soothing voices that told them how to lead a simple life. Saints passed on the age-old Indic wisdom of conquering greed, relinquishing ego and looking inward for the answers. These were distributed knowledge centers providing best practices for leading a fulfilled life.

I saw Sikh monastic orders performing selfless service, young turbaned men working enthusiastically at the langars, hauling heavy cauldrons to feed the pilgrims. Guru Nanak Dev ji gave his blessings to all from the entrance to every Sikh akhara.

In the Kumbh I saw, there were hundreds of foreigners, many of whom were interested in the living, unbroken history of mankind. Others were there to see a show, a spectacle so intense that nothing in the world matched it. Many young Indians were there on a selfie spree. But there were also thousands upon thousands who were there simply because they believed in the wisdom of their ancestors. To them, continuity of a civilization was far more important than trivialities. I implore you to experience for yourself “The Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” when it repeats itself in 2022 at Haridwar. If you stand in aloof judgment, you’ll miss the exquisite layers of an ancient civilization’s wisdom that wants to shyly reveal itself. If you immerse yourself, maybe you would understand a fraction of it.

Dhananjay Joshi, dnjoshi.navy@gmail.com, is a retired Indian Navy engineer devoted to international education who pursues art, history, retelling of Indic stories, photographyand creative writing

Sadhus and Devotees

Interviewing Swamis and Sadhus at the Kumbh

BY RAJIV MALIK

Having covered India’s Kumbh festivities several times in the past (e.g., the Jul/Aug/Sep 2013 issue: bit.ly/2013Mela), our main focus this time was to interview the saints, both famed and little known. This was very much a catch-as-catch-can adventure. Some appointments were arranged months in advance, while other meetings were chance encounters. We met with great success. The interviews provide a clear demonstration of the depth of wisdom available to any Kumbh pilgrim who makes a similar effort.

Questions were prepared in advance by the editors in Hawaii, drawn mostly from suggestions solicited on our blog, Hindu Press International. The saints brought up additional issues, most often a perceived lack of unity among Hindu organizations, the adverse influence of Western culture, the training of future saints and sadhus, conversion to other religions and the shrinking of India’s Hindu population, the collapse of the joint family system and the related issue of couples having only one child.

Throughout the interviews, one term came up repeatedly: sanskar in Hindi (Sanskrit samskara). It is one of those words (like dharma) that defies easy translation to English, in part because it has two meanings. The first is “impression” or “activator,” and the second is “sanctification” or “preparation.” The saints’ use was in the first sense, formally stated in one lexicon as “The imprints left on the subconscious mind by experience (from this or previous lives), which then color all of life, one’s nature, responses, states of mind, etc.” The second meaning refers to the formal Hindu rites of passage, including name giving, first feeding, coming of age, marriage and funeral.

Sanskars in the first sense, the common person would likely tell you, are the good character qualities of a human being found in the Vedas, Puranas, Bhagavad Gita and other scriptures and passed on from generation to generation by parents, teachers, saints and gurus. The mother is the first teacher, and it is her duty, with the help of her husband, to pass on good sanskars to her child. Then it is the duty of the teachers and at some point in the child’s life, the family’s guru. Repeatedly, the saints said the youth of today do not have good sanskars, and variously blamed this on the parents, society, simple greed, Western culture, the Internet and, rarely, on the youth themselves. Here are select excerpts.

The first saint we encountered was Shri Mahant Ganeshananda Saraswati from Nashik, a revered sannyasin of the Taponidhi Shri Anand Akhara Panchayati. As with many of the saints, he congratulated the state and central government for the excellent management of the event. He appealed to Hindus to work together in a cohesive manner, and especially to better connect with the deprived sections of society, as our present inability to uplift them is making us weaker.

Youth, he said, are distracted by so many things today and influenced by Western culture, which makes them reluctant to proudly proclaim themselves Hindus. He implored them to take more interest in their religion, culture and what is happening in the country.

In response to our question, he pointed out, “To say that Hindus should build hospitals and schools and not temples is a view that is against the Hindus. Our temples are the base for our religious activities, essential for our religious lives. Hospitals, schools and colleges should be built; but at the same time, religious life has to continue side by side.”

Ganeshananda is a prominent member of the Akhara Parishad, which oversees all the monastic orders. He said the Parishad keeps an eye on unqualified people presenting themselves as saints, sometimes sending a delegation to talk to them. If nothing else works, they will oust the offender from the saints’ fraternity and recommend he or she be boycotted. In this way, they police themselves.

“I normally do not talk to journalists. I do not know why I have started talking to you,” began Shri Mahant Mai Uma Giri, one of the sadhvis of Juna Akahara at Maiwad camp. She focused her remarks on the issue of marriage. “The institution of marriage is a lifetime bond between two people. Live-in relationships are not a good development, and in this Kali Yuga, men and women are also having extramarital affairs, which is very damaging to the marriage.

“The most important role of a woman is as a mother and a wife. It is the role of the parents together to raise their children with discipline and give them proper sanskars. Today our youth want to live a life without boundaries, a life of total freedom. This mentality is causing a lot of problems for society. Absolute freedom is not available to anyone when we live in a society. We have to light the lamp inside ourselves and not focus completely on our physical demands.”

Shri Mahant Narendra Giri Ji Maharaj, president of the Akhara Parishad and secretary of the Niranjani Akhara, sat for a lengthy interview, which turned into a small satsang for all the devotees waiting for his blessings.

The biggest challenge facing Hindus today, he told the crowd, is a declining population in India, with the prospect to even become a minority in the distant future. India’s family planning programs have only been adopted by Hindus, not by the Muslim community. He is deeply concerned with the support for terrorism found within India.

He expressed appreciation for the media’s coverage of the Kumbh, especially for several months in advance, which greatly increased attendance. He sternly warned against drugs: “Drugs cannot solve the problems of the youth. They can only give a false temporary high. The true high comes when one tries to realize God. The countries that are legalizing drugs will be ruining their own forthcoming generations.” He criticized the controversial assertion that Hindus should be building schools and hospitals rather than temples: “Comparing a temple with a school, college or hospital is wrong because the school, college or hospital does not serve the purpose which is served by our temples. An upset person will go to the temple only.” Like most of the other saints, he criticized the court interference with the Sabarimala temple, pointing out that other religions in India have outright rebuffed court orders aimed at their holy places.

Swami was most animated when talking about caste discrimination. “If from the very beginning we accepted our people of the lower castes, then maybe we would not face the situations we have today. We committed mistakes, too. We practiced untouchability, leading to conversions. I appeal to the youth and all Hindus that if someone asks their caste they must simply say they are proud Hindus and not disclose their jati.”

Our next meeting was with Mahamandaleshwar Karshney Gurusharananda Ji Maharaj, one of India’s most renowned saints. Like others, he is generally reluctant to talk to the press but decided to talk to us. He explained the fundamental concept of the Kumbh, one that we were in fact fulfilling with our interviews: “The idea is that devotees would come with their unresolved problems and questions. For instance, if there is a problem in the family, the family elders should solve it. If they can’t solve it, then the village elders will; if they cannot, leaders of the district or state; and if they can’t, the problem would come here to be considered by the rishis and munis. Out of this wisdom, the problem would be resolved.”

Meeting the Gods, Braving the Elements

The Pontiff of Puri Speaks Out

It required considerable advance work to get an audience with Shankaracharya Swami Nischalananda of Govardhana Matha in Puri, Orissa. His is one of the four monastic centers founded by Adi Shankaracharya in the 8th century. He was one of the few swamis we met who criticized the state’s ruling political party for trying to use the Kumbh “to increase its own clout.” He was also unsparing of sadhus who have associated with political parties, stating they “lack an independent thought process of their own.” He warned about the efforts since Independence to declare one group after another as a religious minority, first the Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs, and now the Lingayats and tribals—saying the end result could be that Hindus will themselves become a minority.

He was also critical of the media, observing that most journalists working for newspaper and TV channels have studied in universities such as JNU where they were influenced by communist ideology. “Such people are dominating the media and mostly spreading anarchy in the name of freedom. They are unable to present the picture of Bharat in an organized manner and only highlight the country’s directionlessness.”

He is troubled by India’s current political parties: “The conspiracy that was hatched by the British to distance our society from dharma and spirituality is being followed and implemented by today’s political parties in the name of development.” Dharma and spirituality, he stated, are being presented in a distorted manner, and few have an understanding of either. In the past, he said, the temples and monasteries were centers of education, defense, Sanskrit, dharma and moksha (liberation from rebirth). Today, he argued, these institutions, including the traditional gurukul system of education, have all come under the influence of secularism. “In such a situation, there is no question of a healthy wave of dharma or spirituality. Rather they are being rubbed down, and in the name of development, only direction-less economic revolution is being encouraged. This is dangerous not only for India, but for the whole world, which even today has very high expectations of India. But India is not fully utilizing its intellectual, defense, commerce or labor power. In fact, other countries in the world are benefitting from our intellectual power, but we have failed to do so.”

Yet, he does see a brighter future. “In the present era of computers and mobile devices, the principles and philosophy of Sanatana Dharma are not just excellent, but the best in the whole world. The nature of the soul and its intellect is biased towards the truth. Even in today’s world our Sanatana principles can be intellectually victorious, which will transform the mind that has been polluted due to the strategies of the British. The principles of Hinduism will be recognized and understood on the grounds of their practicality. The world today has no alternative to the philosophy and vision offered by Hinduism. In the name of development, America and Britain have reached a situation where they see only destruction. That is the reason they have to turn to us.

Getting Lost, and Getting Found Again

On a daily basis, 200 to 300 people are lost at the kumbh; on royal bathing days, the number goes up to 40,000. But while getting permanently lost is a Bollywood plot device, the last time anyone was not reunited with their family within a few days was in 2013, according to Umesh Chandra Tewari. And even then, they were provided transport and, when needed, escorted to their home village. Mr. Tewari runs the Bharat Seva Dal lost-and-found camp, which was started by his father 73 years ago. His children help after school and will take over the camp in the future. So far, in late January when Hinduism Today interviewed him, they had helped reunite 1,100 adults and 12 children with their families. They are prepared to put people up overnight and have separate tents for men and women. Twelve smaller lost-and-found centers are spread throughout the Kumbh area, and the main announcement system covers the entire grounds.

The biggest advancement has been the advent of mobile phones, which make reuniting people much easier. But mobiles have their limits. Tewari says they encounter elders who have a mobile phone but don’t know how to use it. Batteries also go dead.

Elders and children may have a slip of paper in their pocket with a phone number to call if they are lost. “There are groups from rural areas that hold hands as they walk towards Sangam,” Tewari explained. “Some groups hold a flag to identify themselves and for everyone to follow. Even a branch of a tree could be a symbol for villagers. We see this most on the main bathing days when the rural pilgrims come in large numbers. Years back a group would be tied together with a rope, but this doesn’t happen anymore.”

One group we encounter at the camp was searching for their 81-year-old mother. They had left her with a group of other elders while they took their bath, but she was not there upon their return. Another person, a priest from Ujjain, was trying to locate a friend he was supposed to meet.

Overall it is rewarding work, states Tiwari. “Pilgrims experience blissfulness and peace after a holy dip in Ganga. In our case, we get the same kind of blissfulness and peace when we are able to connect lost pilgrims with their family and friends.”

On family, he advised: “Our Hindu identity will be maintained if our parents or elders will teach religion to their children. In the past it was our family priest who used to handle this responsibility. The Britishers, especially Macaulay, understood they needed to end this practice in order to rule us. So our good people were hired by them and became their servants. They created universities and employed our scholars. So, our leadership slipped from the hands of the highly intelligent and competent into the hands of those less so. Then a narrative was created that those associated with Sanskrit were not true scholars.

When our intellectuals were thus taken, then the sannyasins had to come into direct touch with society, even though our householder intellectuals had been the best people to deal with society, as they were married, had wives and children and understood the problems of the people in a much better manner. They were our best leaders. Society used to take care of such intellectuals and scholars.”

The question that brought the strongest response from the Mahamandaleshwar was on women working outside the home. “Today women taking jobs is not for most a compulsion but a luxury born of desire. If they do not have an expensive car or handbag, they cannot live without it. They have forgotten their duties. To become an executive is not very important. To become a real mother and a real wife is very difficult. When one is going out to a job, who will look after the children? What kind of bonding will there between mother and children? Children will not love and respect their mother, which psychologically disturbs the child. How will the children know their own identity? Children, too, are very smart. They understand if they were ignored and left when they were small. Why would they develop a bond with such a mother? So, if the trend is for the women to work, then we have to stand against this trend. Mahatma Gandhi swam against the tide, as did Shivaji Maharaj. If we cannot do so, then what is our own strength of soul or conviction?”

He related the issue to that of live-in relationships, which he finds troublesome. “Marriage is not for a physical relationship; it is for companionship. You feel that you are part of the other. When this drama of their live-in relationship ends, then they will cry and there will be no one to listen. We have to show such people what is going to happen to them ten years from now. Even sex will not make them happy beyond a point, because sex is 95% mental and only 5% physical. If you do not have a close relationship with your companion, what kind of life will you be leading? If you start discussing expenses and try to divide the electric bill and the petrol bill, what kind of companionship will it be? Both partners in such a relationship are just serving their own selfish ends. I’ve seen such relationships break, with unimaginable pain and anguish. It is the joint family system which has been the core of our society and religion, everyone taking care of everyone else. If the institution of marriage is over, then the social life of the society will be over. A lady is the center of the home, and it is she only who can manage the home. Our scriptures have said, ‘Where women are worshiped, devatas reside at the place.’ This is our basic theory. We respect our women.”

Haridwar-based Swami Hari Prakash Ji Maharaj of the Udasin Akhara spoke on the uniting power of the Kumbh. He said it works as a sutra for Hindus, meaning something which sews together (as seen also in the English suture). “We Hindus speak different languages, our dresses, eating habits and traditions are different, but still we are one. When we come here it does not matter if one be Sanatani, Shaiva or Vaishnava. There is no differentiation on the basis of caste or creed. Whatever binds in the sutra of unity is named dharma. If there is something that divides based on opinions, politics or even science, that is not dharma, for true dharma’s characteristics are to unite.”

He feels Hindus face two great challenges. The first is conversion, something which Hindus never did by force or inducement. “Conversion to other religions,” he said, “is very damaging and the government should be doing more to prevent it.” The second great challenge is population control. Hindus are following family planning but Muslims in India are not, even though there are Muslim countries which have successfully implemented such programs—Indonesia, for example. He feels India will not achieve uniform development until family planning is uniformly implemented.

He is unhappy with the self-promotion of certain sadhus, especially through association with politicians. “There was a time when the saints were known for their sadhana and knowledge. If I am craving for honor and wealth, then what was the use of my becoming a sadhu? Sadhus are supposed to be natural, calm and very simple.”

He spoke at length about the impact of the West on India and Hinduism, which he feels has disrupted the happy and contented life that was the basis of Hinduism’s refined culture. For example, he said, “Here husband and wife have full faith in each other, but there in the West, they have separate bank accounts and the marriage can fall apart anytime. Here marriages are permanent; there they are temporary. The outcome of live-in relationships is never good. Western influence weighs heavily on us and has damaged our culture badly.”

Saints of the Khumb

Sadhvi Rakesh is part of Braj Academy, founded by her guru, Sripad Baba, a famous saint of Vrindavan. She feels live-in relationships are not right and will have an adverse impact on the institution of marriage. On the topic of women working, she pointed out that in the tradition of Braj, the gopis not only did household work, but also sold milk door to door. “If they could do it, why cannot our modern women, too, carry out their household and religious responsibilities in a balanced manner. Many of our urban and rural women do help their husbands in their businesses and agricultural work. Out of love one does anything for the family. However, if there is accounting done for everything one does and life partners do small money calculations, then it becomes a different kind of game altogether.”

With regard to the Kumbh itself, she relates, “King Harshvardhan used to bring loads and loads of jewelry, clothes and food which he distributed here. He would go back in just the clothes he was wearing. The Kumbh gives us three sutras: renunciation, love and service. The whole spirit here is of renunciation. No one comes with the desire to take anything back. In the morning, pilgrims go with rice bags and other items which they distribute to the alms seekers and needy. This desire is a very peculiar thing and feeling that belongs only to our Indian culture. This is not seen elsewhere.”

Sthanapati Mahant Ghanshyam Giri is a humble and low-profile saint of Juna Akhara. “The main problem that Hindu society is facing,” he observed, “is due to the divisive politics that are being played. But this kind of churning between good and bad has been happening from time immemorial. The Kumbh itself is linked to the churning of the ocean and the struggle between good and evil. It seems this struggle will continue for all times to come. Hindus are basically united, but vested interests are dividing us.”

On youth, he pointed out, it is the duty of parents, teachers and society to give good sanskars, but the youth of today are not ready to listen to anyone. “They want no one to interfere with what they are doing, whether it is right or wrong. Mobile and TV have spoiled them and polluted their minds; if these were teaching something good, why is it not reflected in their character and behavior?”

Swami Balkananda Giri, head of Anand Akhara, is from Trayambakeshwar, Nashik. He, too, is concerned about the youth: “One of the main challenges is that our new generation lacks good sanskars without which they will not be good Hindus, nor develop spiritual powers. I think the gurukul system should be revived, including for our young sannyasins. If the quality of our sannyasins is good, then more and more educated people will get connected to our dharma.”

“While studying and before marriage, youth must live as brahmacharis. They must live a life of restraint; then they can develop into powerful personalities. I am shocked to know that live-in relationships exist; this is an absolutely worrisome development. What will happen if a child is born? More worrisome would be not having a child, which is against the laws of nature.”

As with many other swamis, he emphasized respect for elders. “We must inculcate in our youth the sanskar to touch the feet of elders, which proves one is humble and a seeker. This has to be logically explained as a means to obtain wisdom, power and confidence. All our scriptures have said that God can be seen and experienced in our mother. This is one of the reasons we touch the feet of our elders. Once understood, this will be passed on by the youth themselves to their children.”

Swami Phool Dol Bihari of the Brahm Madhva Gaureshwar Sampradaya, an elderly saint we interviewed at a Kumbh in the late 1990s, is concerned with the family planning situation, with the Hindu community adhering to having just two children but the Muslim community openly declaring they would have five or more. He warned that now young Hindu couples are having just a single child and “there will come a time when the other religion will start dominating us.” Swami is optimistic about what India can offer to the world. “No other religion which talks of the welfare of all. Only Sanatana Dharma says, Sarve bhavantu sukhina, “May all beings be at peace.” It is we who talk of harmony among all the creatures of the world. We pray for the welfare of the entire world, even of our enemy countries. What other religion has this kind of philosophy?”

Brahmarishi Shrimad Ramkrishnananda, head of Agni Akhara and based in Madhya Pradesh, observed that even under a pro-Hindu government, public schools do not offer any education related to religion. “Convent schools can teach their religion, but we cannot teach ours. That is the reason our youth are becoming atheists. It is not their fault, but due to lack of education.”

He worries about the impact of Western culture on India. “We are gradually getting so influenced by it that we are forgetting our own identity and culture.” He does not feel women working impacts their devotion toward God. “When a girl is educated, naturally she would like to use her talent for the welfare of society. Even if they work outside, they ensure that the household is not ignored or suffer in any way.” He praised the entire Kumbh experience. “See the greatness of our dharma that when one has a holy bath in the Ganga, does anyone ask to which caste, creed or community one belongs to, or whether one is illiterate or a scholar? Those who say Hinduism is losing its popularity must come and see the tens of millions who have gathered, and it increases with every Kumbh. Our Sanatana Dharma is like the sun. Because there are a few days of clouds, it should not be taken that the sun has become weak; as soon as the clouds disappear, the sun shines again in its full glory. The glory of Sanatana Dharma is like that. It has always been there and will remain forever.”

Swami Hridayananda Giri of Juna Akhara shared: “The majority of pilgrims coming to us are seeking material things. They want to attain wealth or be blessed with a child. At the same time, there are seekers of knowledge, who want to fulfill their duties and make the best of the human life they have been blessed with. There is no need to come to us for material things. Those are readily available in the world, though they may require hard work to obtain. Our people should come to the Kumbh as seekers of knowledge. We are happy to guide them on matters related to dharma and spirituality.”

Sadhvi Vidya Giri, a Mahamandaleshwar of Mahanirvani Akhara, pointed out that women have never been confined to their homes and kitchens in India. “We had eminent scholars such as Gargi and Maitri, and warriors such as Rani Lakshmi Bai, Durga Wat and Ahilya Bai. Women played a leading role in the past; today their number has increased and they have established themselves as strong personalities in many more areas of life, not only in India but all over the world.”

Spartan Accommodations

Swami Divyananda of Chitrakoot Peeth, Vrindavan, spoke, as did many of the swamis, about the Ram temple in Ayodhya: “Not being able to build the Ram temple is one of the biggest weaknesses of Hindu society today. There is so much politics around the temple, and it is in the courts also. Ram is loved not only by Hindus; even Muslims respect Him, yet He is placed in a tented accommodation in Ayodhya. We are also divided by caste because of vote bank politics. The saints should not be involved in politics but hold the interests of Hindu society uppermost. The day we are united, not only the Ram temple, but all our major issues will be resolved. “I am worried that the number of youth coming to our ashrams aspiring to be saints has gone down. The controversies related to many saints have put off the youth and made them more distant. Things are changing fast, and the saints should be changing fast as well to keep pace.”

Sadhvi Divya Giri of Juna Akhara, head of Mankameshwar Math Mandir in Lucknow, addressed the state of women today. “On the question of the role and life of women today, my views are a little different and may or may not be liked. When women become career oriented, they become more ambitious. They want to excel in their field and at the same time they have to look after their household. If they cannot manage the home front, they feel guilty; whereas men are free from household responsibilities and focused on their career only. As women become career oriented, our coming generations have started to suffer. Care of the children is left to servants. The solution is not simple, but we have to ensure that women do not have to work under pressure and also can choose an area of work close to their heart.

When women are overburdened with the responsibility of career and household, they suffer from physical and mental stress-related diseases. In the race of life they are not able to take care of their health and well-being. When women take up a career, marriage happens at a later age, they are not able to conceive children in a normal manner and opt for test-tube babies. It is also not possible for busy couples to have more than one child. If this goes on, people will miss out on a joyful and fulfilling life. We need to seriously contemplate how much we can work, how long we can work, and in certain cases whether it is needed for the women to work at all.”

Summarizing the Saint’s Views

As a whole, those we spoke with are concerned and upset about the Hindu youth being influenced in a big way by Western thought and lifestyle. Many saints are struggling to master social media techniques and know-how to connect and convey their message with youth to follow the path of dharma and righteousness. Almost all said it is high time that parents join hands with the saints, teachers and spiritual gurus to pass on the message of our Hindu heritage and traditions in a scientific and down-to-earth manner.

Varied Forms of Blessing

CONCLUSION

Overall, the Kumbh Mela 2019 was a resounding success, and not just for the record-breaking numbers who attended. The advance planning, infrastructure created, overall cleanliness and management were unmatched by any past Kumbh. There simply were no incidents beyond the occasional medical emergency, opportunistic theft or separated family member. I and my wife Renu (attending her first Kumbh) were deeply impressed and touched by the army of saints we encountered. Each worked with dedication and commitment, some almost round the clock. They made best use of the golden opportunity that the mammoth event provided them to give darshan and convey the message of our Vedas and Sanatana Dharma. We hope that through our interviews readers will get a sense of the wisdom available at the Kumbh by merely walking in the door of any sadhu camp, approaching with respect and posing sincere questions.