Over a period of 30 weeks each year, tens of thousands of children in North America, from kindergarten through grade twelve, follow a syllabus based on Advaita Vedanta to prepare them for a spiritual life

By Nimmi Raghunathan, California

All images courtesy Chinmaya Mission

It was 1965 when pujya gurudev swami Chinmayananda made his first visit to the US—to the San Francisco of social commotion of experimentation, peace, and New Age ideas. His first three-day lecture series stateside was impactful enough for him to come back every year after that.

This guru was different. He did not think his task was to just pop up, talk to a group of people, jet back to India, and forget about the seekers and the curious. He took them seriously. Decades later, Swami Swaroopananda, Global Head of Chinmaya Mission, smiles and says, “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—the whole world is one family. That’s the message of our rishis; and when Gurudev set up Chinmaya Mission West (CMW), he demonstrated commitment right then. It was a signal to the people that we are with you. It was a permanent idea.”

Flashback again. It was 1973, and Gurudev Swami Chinmayananda was in Long Island, New York. Sharada Kumar was accompanying him and chanting the Bhagavad Gita, as she had always done at his satsangs. At bhiksha one evening, he instructed her, “Start Bala Vihar.” Sharada Kumar, who had a 3-year-old at the time, was nonplussed. “What is that?” she asked softly. “When you go to Mumbai, meet Nirmala Amma,” came the reply. Some years later, Darshana Nanavaty, who today is the director of the Bala Vihar (BV) program at CM Houston, had a similar experience. “Take care of my children,” Gurudev told her. At the time, she had no idea what to do with that instruction.

The two of them did not know then that the loving directive they had been given would have far-reaching consequences. With several hundred volunteers and dynamic swamins (this term includes both men and women monks), it would balloon to touch the lives of thousands of Indian American children, laying the foundation blocks of Hindu values and shaping their perspective of life through the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta.

Sharada Kumar, who is now CM’s National BV Coordinator, says, “I had to start from scratch,” reminiscing how Nirmala Amma, who ran a BV in her apartment in Mumbai, gave her tips on constructing a curriculum. Darshana Nanavaty remembers immersing herself in writing, collating and creating small books of teaching material and taking them with her to show Gurudev at a camp at the ashram in Piercy, California, seeking his guidance and approval. She recalls a fellow devotee, the late Susheel Bibbs, who lived in Piercy and had worked on the Sesame Street TV show, pitching in ideas on how to make things appealing for kids.

Students

Of course, having teaching material is one thing—getting an audience for it is another. As every early volunteer in every center across North America reports, the children at home and their young friends become the first students.

Bala means children and vihar means play. This, even the very first homegrown teachers of CM understood. In pre-Internet days, they scrounged around for craft ideas to supplement their teaching on Diwali and Navaratri. Anyone traveling to India was tasked with bringing back animated books on the Gods. Some translated bhajans into English and had the kids mime Lord Hanuman’s power and Krishna’s playfulness. It was all fun.

Today, for many in North America, Chinmaya Mission is synonymous with Bala Vihar—a far cry from its inconspicuous beginnings, where little groups of children met once a week in Los Angeles, San Jose, Boston and Chicago, in the homes, basements and garages of their parents. The remarkable truth of this expansion is that its success has been purely driven by word of mouth. Communities will be hard-pressed to find glossy printed testimonials and television ads; but an anxious parent of a toddler has to simply utter worried words like, “culture,” or “learning about Hinduism,” at a gathering, and he or she is likely to be informed about CM and the efficacy of its BV program by a parent who has had a child attend.

Initiatives

Along with growth came more initiatives. Children began to get grouped grade-wise so instruction could be more targeted. Shlokas were incorporated to suit the age level. Sets of prayers were assembled, including those invoking the Gods Ganesha and Saraswati, and chanted at the start of class. Other sacred verses were compiled, with Shanti Path mantra at the end of the class.

Gaurang Nanavaty, the dynamic founder of CM Houston, points out that not only was chanting taught but “emphasis was laid on what the Sanskrit words meant, so children would comprehend, internalize and make it their own.” Growing up primarily with English, students were provided not only translations but transliterations of the material.

North American Bala Vihar children over the years have embraced this fully and become so precise in their pronunciation that they have gone on to shine at Gita chanting competitions in India.

Teaching

As the BV movement began to spread, the CM communities in some cities grew sizeable enough to band together and buy properties to establish centers. Today, while the newer and smaller chapters rent rooms from schools for the weekend to conduct BV, many others have constructed small and large buildings with the help of member donations. These buildings tend to have classrooms equipped with TV monitors to help in instruction, a satsang hall, an altar and resident quarters for the head monk of the center.

Other BV matters began to formalize, too. Families began to pay an annual BV donation or fee, to have their children attend. No longer homegrown, volunteer teachers are now vetted and handpicked by either the swamins or senior sevaks of a center and then trained. In Los Angeles, for instance, with an eye for quality instruction, all teachers are required to complete the online Foundation Vedanta Course administered in India by scholars and Vedantins. The year-long program is supported with in-person weekly satsangs by Swami Ishwarananda, the learned head of the center. Teachers at the various centers also attend satsangs, study groups and converse over online forums.

CM Los Angeles has also instituted an Education Council comprised of senior teachers and sevaks, whose job is to mentor teachers throughout the year and keep an eye on the prescribed curriculum.

Brahmachari Soham Chaitanya, the young head of CM San Jose, who was a BV student in India and then briefly taught BV in North America before becoming a monk, says there are advantages to a structured syllabus. “Once the teacher gets comfortable with the topic, it allows them to be creative in their presentation,” he says. “They don’t need to spend too much time thinking about what they are going to teach in the next class.”

This allows an age-appropriate curriculum which is, for example, “effective in engaging high schoolers, since they are entering a phase where they appreciate more discussion and relatable examples.” Indeed, teachers are encouraged to pique the interest of students and allow them to question freely. And children are known to demand answers to why Lord Ganesha’s head had to be cut off or Rama’s father had so many wives!

Trained in Vedanta, teachers of younger children provide answers while those of older ones encourage students to introspect further and understand their role in society, through the prism of dharma and universal values such as tolerance and compassion.

Discipline

In the event that a chapter or center has to deal with, say, a less than committed teacher, the volunteer is gently directed and reassigned to another needed volunteer task. “Whichever center it may be, there is no question they are dedicated to CM but it could be their talent lies elsewhere,” explains Swami Ishwarananda, “No one has to leave, and no one is told to leave.”

Discipline and handling truancy in the case of children, too, is sought to be done as gently and firmly as possible. Teachers and senior sevaks first try to talk to the child and after this, the parents are looped in. Again, in infrequent situations, when this action draws a blank, the request may be made to withdraw the child from the program.

Flexibility

Whether it is about incorporating new topics or tweaking teaching methods, both Darshana Nanavaty and Sharada Kumar say it comes from being open to teachers’ feedback while also keeping their ear to the ground on the needs of the children themselves.

This flexibility, as any teacher will attest, is key to being heard by the student. Brahmachari Soham Chaitanya believes that among the top three reasons the Bala Vihar program has met with success is the “decentralization of operation.” So, while CMW provides broad parameters on education, individual centers are free to study their youth and structure materials and teaching to suit.

To gain a deeper understanding of Hindu beliefs and practices, teachers bring to the class several thoughts and works that are not necessarily Chinmaya Mission publications but are within the ambit of Advaita Vedanta. They also plan field trips to observe temple rituals and include visits to other faith centers like Zoroastrian and Buddhist temples, synagogues, mosques and churches.

Some larger centers with deep teacher talent, guided by learned swamins, generate books on subjects geared to specific grades. In Los Angeles, teacher groups under the supervision of Swami Ishwarananda recently concluded a project based on the acclaimed ”Upanishad Ganga” Indian TV series that was commissioned some years prior by Guruji Swami Tejomayananda, the previous head of Chinmaya Mission Worldwide. From grades 9-12, students delve into Vedantic concepts with an eye on applicability in their impressionable lives.

Others have worked on character studies of main figures in the epics to teach values, and yet others have researched and collated information on particular Gods, like Lord Shiva. The independent and creative approach tends to be effective and beneficial for all, as the material generated is made accessible to all centers.

Distribution

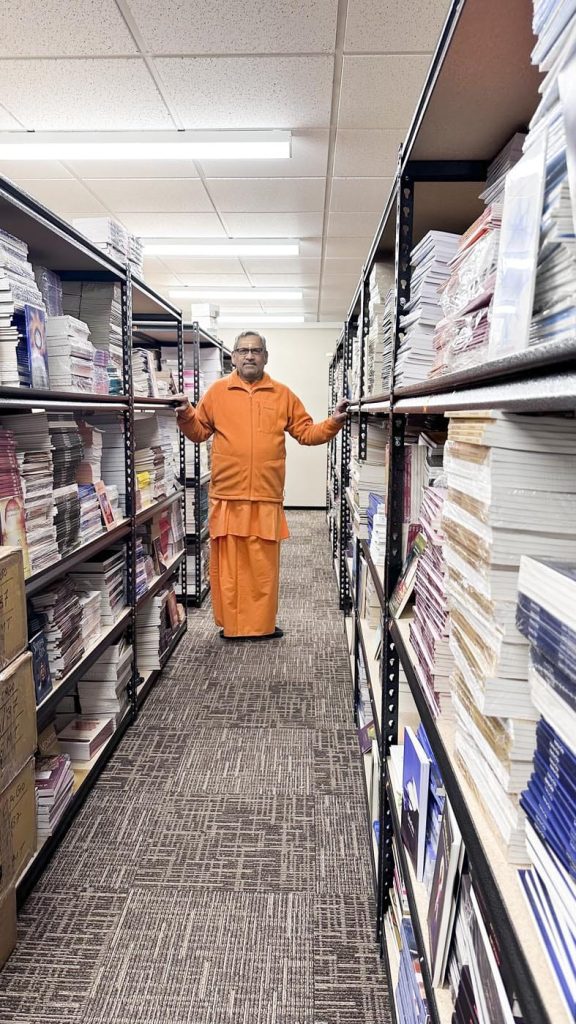

The clearing house for this is in Pennsylvania, where Chinmaya Publications West goes on overdrive at the start of a new year. Swami Siddhananda, who heads this, estimates that “in the very busy months of September and October, an average of 500 books are shipped out every day by UPS.”

Throughout the year, he says, teachers’ needs are met through smaller packages. Storybooks, gift items and audio-visual materials to supplement instruction are often requested and sent out to centers and chapters across the US and Canada.

Parents

Often in tandem, books are ordered for adults—the parents who bring their kids to Bala Vihar. While the child is busy in class, parents, too, have the opportunity to learn Advaita Vedanta from an Acharya. The Bhagavad Gita, Tattva Bodha, Atma Bodha and other texts are addressed by the teacher.

No doubt exists in the minds of Swamins, teachers and volunteers that parents are key to a successful teaching experience. A child can come weekly for instruction, but the practicing and internalizing can be nurtured only in the home environment. When adults are steeped in the same knowledge, the dissonance is absent, making them effective guides.

Many immigrant and young parents approach CM fearing that their children, growing up in North America, will alienate themselves from their roots. They tend to believe that just having them chant shlokas and sing bhajans will assuage their concerns. Attending the mandatory adult classes tends to be eye-opening for them, too! They join in learning the simple rationale behind why coconuts are broken at the altar and proceed to understand the need to joust with the ego.

Gaurang Nanavaty echoes a common sentiment while explaining why at least one parent must attend the adult class. “When everyone learns, not only the child but the entire family grows, and then the society, the nation, grows,” he says.

Adult members at different centers often recall the bonding that takes place with a simple activity like staging a play. Someone will write a script on the life of Lord Rama, another will go down a rabbit hole looking for props, others get involved in costuming, scheduling rehearsals, recording the music. Not only do parent and child spend several hours together, but participating families bond over a shared goal and philosophy.

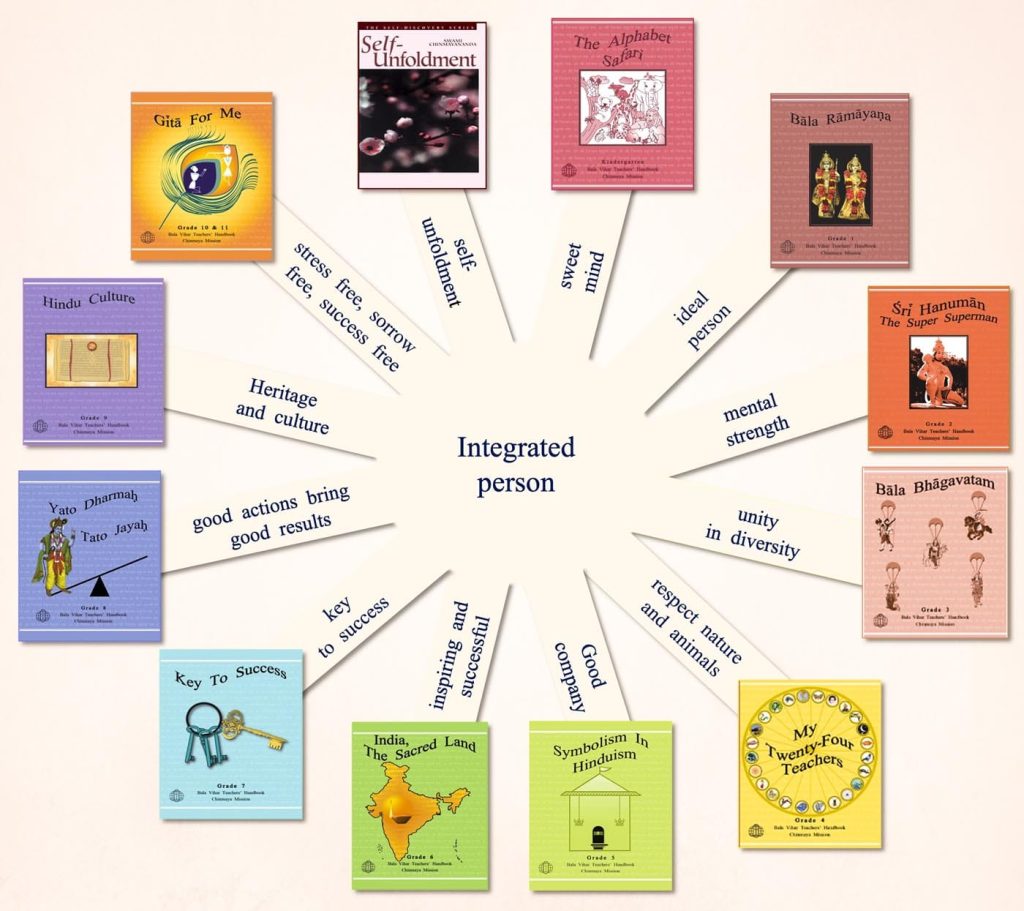

Curriculum

“Remember that values are more important than valuables,” Pujya Swami Tejomayanada has noted, and Chinmaya Mission emphasizes and prides itself on the systematic value-based education it provides for children. It starts in pre-kindergarten, where tiny tots are nurtured in play and Hindu culture, and then moves on to the celebrated Bala Vihar program for children in kindergarten through grade 12. The structured teaching is done with Advaita Vedanta forming the basis of all understanding shared in class.

Jignesh Joshi has been teaching high schoolers at BV in San Jose for over 15 years. The goal, he says, is not to have children emerge “as realized masters or little monks, but to instill the preparatory qualifications with applicability in their daily life.”

CM teachers say this is different from public education, which is aimed at increasing the standard of living, while their work is to increase the “standard of life.” They also rush to point out that this does not negate success at work and business but helps enhance self-growth, creating well-adjusted individuals who become outstanding citizens of society.

And so, spiritual values from Hindu texts are stressed. Joshi gives an example of the Shat Sampati, which is part of the Sadhana Chatushtaya as enumerated by Adi Shankara. “We have the students view the qualification of shama (tranquility) as learning to manage the mind, and dama (training) as managing actions.”

At CM San Jose, grades 10-12 study the Bhagavad Gita, with the eighteen chapters neatly divided over three years, relying on Swami Chinmayananda’s commentary, The Holy Geeta. “The Bala Vihar calendar gives us 30 weeks to get across the Vedantic concepts and values,” says Joshi, “and this is possible only because the building blocks of learning have happened in the early years. It is like an assembly line in an auto factory, where each part is put in the right place before the car rolls out, but done in a thoughtful, personal, and considered manner.”

Ameetha Ramesh, who teaches high schoolers at CM Branchburg, New Jersey, says, “The eighth and ninth grades are especially sensitive. This is the age when they get skeptical and demand to know what is so special about being Hindu.” So, she says, the work begins in grade seven, when children study the book by Swami Tejomayananda, Hindu Culture—An Introduction, which deals, among other things, with the basis of cultures, fundamentals of scriptures, role of temples, indicators of dharma and understanding the caste system. “By middle school, it’s important to have them feel pride in their culture and who they are,” she says.

The stepping stones to this moment stretch back even farther. In kindergarten, kids are familiarized with simple values initiated in an “alphabet” curriculum. While the instinct of every child is to say, “A is for Apple and B is for Ball,” the Vedantic alphabet at CM goes, “A is for Aspiration, B is for Brotherhood and C is for Cleanliness.” Truth, Devotion, Victory, Work, Kindness, Love, Yagna, Zeal…. The kindergarten tots at the end of the year can rattle them off with glee at their annual graduation presentation.

Importantly, teachers don’t teach each letter of the alphabet in isolation. Victory, for example, is explained not only by narrating the Aesop story of the hare and tortoise. Instead, the difference between competition, winning and competing is gently explained and then tied back to the first letter, A, in the context of Aspiration.

Several teaching elements accompany each letter of the alphabet. In I for Intelligence, for instance, teachers try to prod an early understanding of the mind, asking the children to think about what is different about their mind from their pet’s at home. Children also hear the story of Lord Ganesha circling His parents, and do art projects based on what the teacher judges the class can handle. With the ground set for storytelling and desirable values recognized, the elementary grades dive into learning about the Ramayana, Bhagavatam and Mahabharata. They are introduced to heroic characters and villains in each; a sort of Bollywood-like stark good and bad!

From here individual centers diverge and do what they think the student body requires. Some will have their children, by the time they are in grades four and five, studying the characters from the epics in a more nuanced manner where teachers find themselves answering questions about a “poor Sita” and an “unfair Rama” or leading animated discussions on women’s freedom as Gandhari blindfolds herself as the wife of a blind man.

Some centers move to give their students exposure to other material in Hindu literature. A year will go by delving into the lives of the saints of India, stories from the Upanishads, or studying a commentary on the Vibhishana Gita, where children essentially learn that being equipped with inner values alone brings lasting success and happiness.

At CM Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, high schoolers are now learning from Drop—A Novel. This book, initiated and seen to fruition by Chinmaya youth, has as its protagonist an Indian American character traveling to India after a painful experience. “That we are learning through an Indian American experience makes a difference,” says Raj Daswani who has been teaching here for about a decade.

He recounts how, when talking about India, its history and some geography, children would ask why that was important. “They would say, ‘I am American’ and we would have to navigate that and explain how each of us is a combination of both, American and Indian.” Bringing a more contemporary book into class along with the Gita has stemmed dropouts, he says. “They are interested. They identify with what’s going on. Some of the language sounds like them now, it isn’t esoteric anymore,” he says.

Ameetha Ramesh says they are piloting a program dubbed “BV 3.0,” which incorporates seva. Younger-grade children this year made New Year greeting cards for veterans and residents of senior homes after learning the teachings of Sanatkumaras and understanding the concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam. “Practical understanding and relatability,” reiterates Raj Daswani, are important.

The importance of relatibility is also recognized in CM Seattle, Washington. Co-teachers—past graduates who are either working or are still in college—have been assigned to grades 5-12. The aim is to identify even more of them so the younger grades can also have a Chinmaya youth in class. “Age cannot be a criterion when developing the culture of giving back. It should start now. It should start today,” says the center’s coordinator, Sujatha Aswath, pointing out another advantage.

“Honestly, this is great,” says Archish Sridhar, a BV graduate, a current senior at the University of Washington and an assigned co-teacher. “If there was anything I felt was needed when I was a student,” he says, “it was more overlap between younger and older students.” In his estimation, “The older ones learn responsibility as role models, and the younger ones will have someone to look up to.” In his ideal world, “Older kids should know the names of the younger ones and call out to them by name as they pass by in the corridors.” As part of his responsibilities as a teacher, he says he makes it a point to talk to the students about what is transpiring in their lives and to serve as a mentor of sorts.

His brother Sidh Sridhar, in 10th grade, in his youthful, experienced wisdom says that there has to be push from parents, too, for students to remain interested. “I remember not liking pujas when I was younger. But I don’t see it that way anymore, and I think I have gained,” he says. At home, there was no question of not going to BV, even if you pleaded boredom.

Ameetha Ramesh says in their pilot program they have looked into the parent angle, too, and have incorporated a “parent talk series” where the adult goes in to narrate a story or engage the kids, supervised by the teacher. “Children take pride in seeing their parents teach, and the adult gets invested more,” she says.

Reflecting on his experience, Jignesh Joshi surmises that the material that teachers bring into class is great, but what changes are the methods of teaching in keeping with student needs and the proclivity of the teachers themselves. Someone may be happy getting things across through music, someone else through slides, and yet another through games, for example.

Getting the students on board can often be accomplished only through discussions. Joshi readily acknowledges, as any good teacher, that sometimes the students can pleasantly flummox a teacher by thinking outside the box: a student once wanted to know why God couldn’t be more discerning and only remember her good karmas and ignore the bad?!

Teachers are sensitive that their classes are pan-Indian and address subjects accordingly. Ameetha Ramesh says vegetarianism “can be a sticky topic,” and emphasis is laid on not hurting anyone’s sentiments. “The point,’ Jignesh Joshi sums up, “is that what we have is a living curriculum.” And the teachings live through the lives led by students.

Shobha Ravishankar of CM Houston, who has taught children for over 20 years, says, “Bala Vihar is education for life. Once the child goes through this value-based education, you won’t see the change immediately because it is abstract.” She explains, “The child will personalize it, and then we can see the inner success that makes them happy and fulfilled.”

E-Balavihar

At the height of the lockdowns, in 2020, when children were confined at home and occasionally shepherded to outdoor open spaces for a break, Chinmaya Mission West thought an online Bala Vihar program would be a practical response to continue serving families and maintaining educational programs during this time of physical isolation and uncertainty across the globe. The swamins and brahmacharins in the US and Canada inspired sevaks and members, and together they swiftly drew up a syllabus. The response was equally immediate: 5,000 children across North America registered and made the shift to online education that summer.

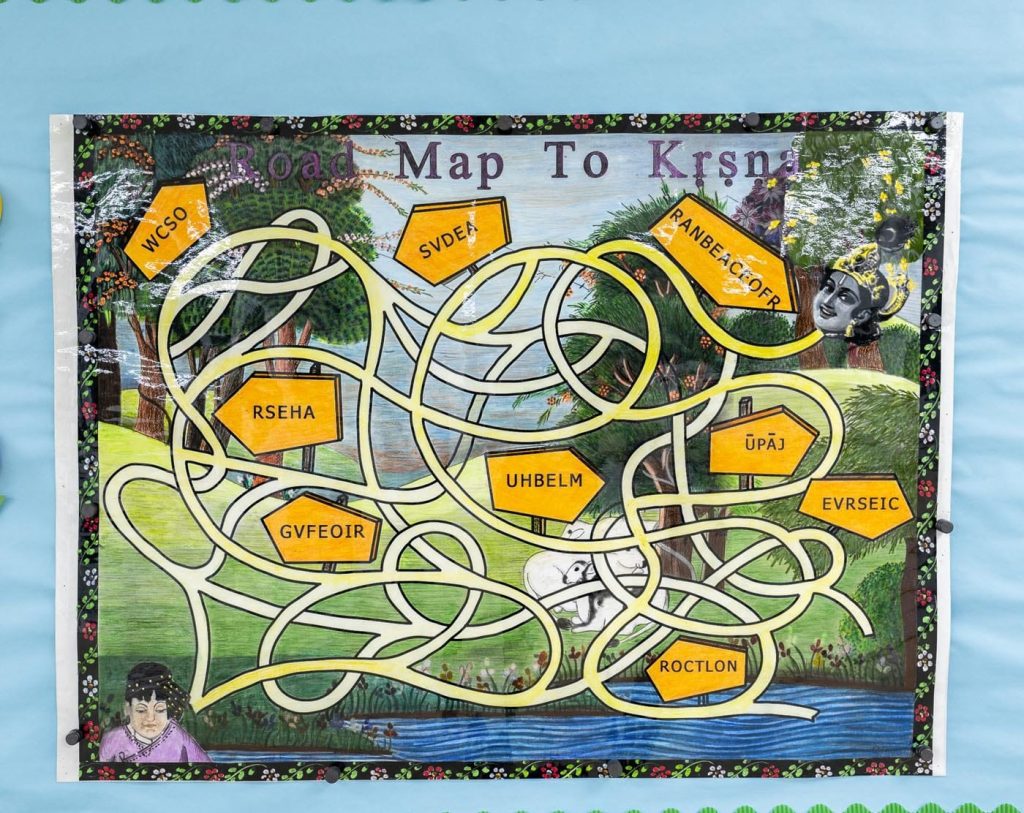

Of course, there were hiccups between conceiving and implementing the digital Bala Vihar: Teachers of younger children had to figure out how to engage without craft projects, and how to prod older children, already tired of sitting in front of computers for school, to blink their bleary eyes. Swamins, brahmacharins and youth class volunteers again showed initiative, embracing and deftly adapting to teaching the Mahabharata through song, puppetry, interactive discourses, and even virtual escape rooms and treasure hunts!

Classes were conducted daily Monday through Friday, for eight weeks, and teachers were happy to build on spiritual ideas day after day, without losing momentum. The children, even through this new form of engagement, made friends and bonded with their teachers over Hindu culture. As the e-Bala Vihar experience continued in 2021 with the teaching of the Tulsi Ramayan, some key data emerged: many enrolled students were from areas in the US that did not have a physical Bala Vihar presence.

Later, when things began to limp back to normalcy and students at the various centers made it back to in-person classes, Chinmaya Mission pondered the information gained. Could the successful digital program be geared to help children who live in smaller, more isolated communities? Guided by the CMW board, headed by Swami Shantananda in New Jersey, and without much advertising or fanfare, the decision was made to continue the e-Bala Vihar program.

Starting as a five-month pilot in 2022, it is now a year-long 2023-2024 program and is geared specifically for families who live at least 50 miles from a physical CM center or chapter. The enrollment has been from small Hindu communities in states like New Mexico, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Idaho, Mississippi and Alabama, among others. Geographically distant places in states with strong CM presence like Texas, Illinois and California joined as well, says Brahmacharini Akalka of CM Trinidad, who now guides the program with a teaching team that consists of trained Chinmaya Yuva Kendra (youth group).

And just as with in-class Bala Vihars, always recognizing that parents learning alongside their children enhances the spiritual foundation and education of the young at home, the e-Bala Vihar program also runs concurrent classes for adults led by sevaks.

Looking Forward

One who can look back with clarity on this is Sejal Shah, a proud second-generation CM teacher who teaches at CM New York, including her daughter, the third generation of the Shah family! “I didn’t realize how blessed I was until I had my own children. I was blessed to have parents who saw the value of spiritual education just like many did with other extracurricular activities such as sports, music, chess, etc., and made it a priority.” (See earlier sidebar, page 21, for more.)

Alumni like Shubani Chaitanya, Soham Chaitanya and Sejal Shah—and there is a growing, visible trend—who plunge themselves back into BV in new roles as monks, parents, teachers and volunteers, are the kind of testimonial that CM celebrates. For it seems very clear, now, that the future of the third-generation Hindu American and Hindu Canadian is rooted and stable.

Misson Numbers in North America

❃ Almost 20,000 children enrolled in Bala Vihars today

❃ Bala Vihars with more than 1,000 children are located in San Jose, Los Angeles, Ann Arbor, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Washington DC and New Jersey areas

❃ 300 teachers in Chinmaya Mission San Jose, which has over 2,000 children

❃ The region with the largest number of chapters (affiliated to a larger center and administered by the center’s board of directors) is Los Angeles area, with nine

❃ The oldest Bala Vihar was started in July, 1976, in Long Island, New York

❃ The newest center with a Bala Vihar is in Cleveland, Ohio, with 75 children

From Student to Teacher

By Sejal Shah, New York

I am a proud CM Bala Vihar alumnus. My parents joined Chinmaya Mission in 1978 after meeting Gurudev and have stayed active till the present day. We started BV by rotating from basement to basement of uncles and aunties. Our beloved Vilasini Balakrishnan (CM Washington Region) was our first teacher when I was growing up in Michigan.

Going to Bala Vihar every week during the school year was all I knew. Being Hindu was a normal part of my identity. I took chanting and singing bhajans for granted and thought that was what every Indian does. I was surrounded by a community of like-minded peers and adults who created a safe space for learning and expressing this rich Hindu heritage.

Even today I am still in contact with many I grew up with in Bala Vihar, and I consider them as family. No matter how long it’s been since we last met or spoke, the thread that connects us is still strong. When I meet alumni from other centers, there is already an underlying connection, allowing for another thread to be woven together.

As an adolescent, I started to develop a comfortable, underlying pride in having this Hindu heritage be a part of who I was. One of its expressions came out through my love of Bharatanatyam. I went to a Catholic high school, and through religion, I had an opportunity to confidently connect with my peers of other faiths.

I wanted my daughter to have this confidence and pride. And that is when I came back to CM. My parents, Krishna and Jagdish, led by example, and I want to do the same for my girls.

Of course, it is different now. Growing up, my parents allowed one TV and phone for the entire family. This limited our distractions and made it ideal for my parents to raise us with a Hindu spiritual education. It’s different today. As BV teachers and parents, we must embrace the fact that technology is a constant in most teens’ lives. We will need to learn how to use this evolving technology to build interesting avenues for Hindu spiritual education.

The Head of Chinmaya Mission on North American Youth

Swami Swaroopananda, global head of Chinmaya Mission, held a Q&A with Hinduism Today during his visit to CM Los Angeles, summer 2023.

In your global travels, have you observed differences between Indian American children and others?

Each place has its unique lifestyle, which is always in a state of flux and can be experimented with. This is not to be confused with culture, which is Sanskriti, that which improves you and is practiced for a long period. Going to bars, doing drugs, dating, etc.—even the West doesn’t call it “culture,” but people loosely do it all the time! Youth everywhere tend to be the same, but depending on whether there is a background of culture in a home, the approach of children can be different.

In America, what is happening is that there is a huge new immigrant population who have brought their culture with them and want their children rooted in it. So, there is this surge of interest in culture. In other places where there are old settlers, just like with the first generation of immigrants in America, the cultural links with India slowly begin to fade. The children reflect the predominant population of the moment.

Should the BV teacher then cater to the needs of the child?

The beauty of Hinduism and CM is that we are adaptable but remain firm in our base. Language changes and we must adapt. There is so much talk now about attention span, especially after the pandemic, that has to be addressed. Some adaptabilities take time, but we must always patiently make the effort to reach the child. Gurudev did not waver from the foundation of the teachings but was able to present the knowledge in a way that reached people. We only have to follow his example!

To help the teachers stay the course and engage with the children, we make every effort to send those swamins and brahmacharins who are flexible and with the times, to lead the North American centers.

Adaptability comes with a cautionary note. The tendency to please and cater should not be there, it cannot come in the way of learning. If that happens, then the children won’t be helped. But by recognizing the needs, the standards can be improved.

How does CM keep connected with the youth?

So many, many youngsters have gone through the program, and the expectation is that ALL of them should come back. We should not do that. Gurudev gave knowledge freely. Today also there is no psychological or other binding pressures on anyone to be with CM. Those who are here are here because of a sense of gratitude and dedication. We believe the more the people voluntarily dedicate themselves, the more we can grow our services effectively and joyfully.

When kids go away to college, the link weakens, but now with a lot more centers and online programs, we have more effective ways of being in touch. Centers also know that work should start two or three years before children leave for college, so they remain inspired to continue their connection with CM.

One thing is clear: when the whole family is involved, the rate of children coming back rises even more.

What do you wish to see happen with BV in North America?

Hindu culture should reach the maximum number of people, and our children should be ever ready to serve.

By Brahmacharini Shubhani Chaitanya, New York

Om…Om…Om…The sound of three Oms resounded in my ears. As we sat on the floor with our legs crisscrossed, we began to chant together, in a natural harmony that made it so much more vibrant and alive. This felt comfortable; I felt at home. This was Bala Vihar. Bala—child; vihar—a place where children enjoy.

I was only a child then, living in Manila, Philippines, staying in a country where almost 80% of the population were Roman Catholic. I went to a Catholic school where I was exposed to Christian values. I attended Mass at school and learned all the prayers and hymns by heart. However, deep inside, I also longed to understand my own culture and religion. Every night, I watched my dad clean the images at our mandir and close his eyes in deep prayer. Every morning, I heard my mom chant mantras and hymns in the mandir, but what did that all mean? What did it mean to actually connect to God, and who was God actually? What was this all about?

It is the sheer grace of the Guru and the wisdom of my mother that led me to Bala Vihar. Bala Vihar in Manila was just a five-minute walk from my home. It was not only a place of learning about Hindu culture and religion; it was also a safe and fun place to connect with a community of like-minded people. We had Bala Vihar every Saturday at an aunty’s home. She graciously cleared her entire living room so that we could all sit on the floor, wide-eyed, to listen to the stories of various forms of Bhagavan and Bhagavati. After that, we all went for arati and as we left her home, all of us got a chocolate biscuit sandwich as prasada. Through these weekly sessions, we got more in tune with our culture and also in tune with each other. The best friends that I have ever had were from the formative years of Bala Vihar, because our friendship was rooted in deep spirituality and connection to the Higher and not just mundane day-to-day interests.

As we all grew, we slowly entered CHYK or Chinmaya Yuva Kendra. This time, our teacher was a bit stricter, a bit more serious and she went much deeper. I remember her particularly teaching us the Hanuman Chalisa, going through the meaning of each and every verse. She even gave each of us a printed book with the verses and meaning, which I still have treasured on my bookshelf today. Since then, Sri Hanuman entered my heart, never to leave again. Slowly, this environment became everything in one—it became my home, community, family and, most of all, my deep connection to Divinity.

When I was around 16 years old, our family suddenly had to leave Manila and move to America. This was probably one of the toughest things I had to go through. The toughest thing was to leave all of these connections. Would I really ever get them back? I was going to move to a new place, a new country with a whole new set of people. What was it going to be like?

It was challenging. For years, I was not connecting deeply with any community of sorts because I was just trying to adjust to a whole new education system and find a job so I could be financially stable and secure. I was away from Bala Vihar and Chinmaya Yuva Kendra, and I just focused on getting myself established in the material world. But when I did, I noticed that I was spiritually starving. I was materially full and yet spiritually starved. And when I thought about it more deeply, I realized I missed what I had in my childhood days. I missed Bala Vihar. I needed to reconnect somehow. So, I took a sabbatical to fill my spirit. This led me to pursue the YEP (Youth Empowerment Program) and eventually led me to the portals of Sandeepany Sadhanalaya for the two-year Vedanta course. After this, I was initiated into the path of brahmacharya.

It was the seeds sown in Bala Vihar that led me to this life of brahmacharya. For that, I am forever grateful to Pujya Gurudev, Swami Chinmayananda for creating such an opportunity for people like me, who lived far away from Bharat and yet had access to our culture and religion from a very young, formative age.

As a brahmacharini in Chinmaya Mission New York, I now have the opportunity to share those very same teachings that I learned as a child with many children, youth, and even adults through our weekly satsangas. I feel truly blessed to share the joy that I have received. Bala Vihar connected me to my culture, religion, family and community. But the deepest connection it has led me to, is the connection to the Divine Self—one that can never be lost, one that cannot be gained, because it was always there all along. I just didn’t know it.

About the Author

Nimmi Raghunathan is an editor and published author living in the US. She is interested in comparative religion, exploring historical, traditional and philosophical links to Hindu thought and culture while traveling. nimmicmla@gmail.com

Great effort but current threats to the Hindu community must be taught as well.

It’s not enough to teach values.