Celebrating the life, virtues and spirituality of a few of Bharat’s remarkable Hindu women

BY LAKSHMI CHANDRASHEKAR SUBRAMANIAN

Hindu scriptures hold women in high esteem because of their ability to engage in bhakti more effectively than everyone else,” states Sri Krishnapremi Swamigal of Paranur. “Why? Because their heart, mind and body are gentle and innately devotional, a necessary quality for a devotee’s heart to melt in surrender and devotion unto the Lord.”

Our utmost gratitude to Sri Krishnapremi Swamigal of Paranur, an illustrious 20th-century saint and scholar whose works have been the cornerstone of this Insight. The idea to write about these awe-inspiring women came from Smt. Vishakha Hari’s Iconic Indian Women, an adapted English translation of Sri Krishnapremi Swamigal’s Tamil treatise Sati Vijayam. The book details biographies of 103 powerful Hindu women of India—Goddesses, celestial women, seers, queens from the Puranas and Itihasas, warriors and bhaktas—who excelled in devotion, education, art, bravery and politics.

Hindu devotees have worshiped Goddesses since time immemorial. But that isn’t all. “India doesn’t just worship women Goddesses, but women as Goddesses,” emphasizes author Vishakha Hari. Indian culture has nurtured and revered wise, progressive, spiritually advanced women throughout history.

In this Insight, we delve into the lives of seven such luminaries: Arundhati, Devahuti, Gargi, Ghosha, Vakdevi, Auvaiyar and Vasuki. Some were princesses who married great Hindu sages. Others were born to rishi parents who nurtured their interest in spirituality from childhood. A few, like Vakdevi and Ghosha, were expounders of Vedic hymns; others, brilliant philosophers like Gargi, are spoken of in the Upanishads; and still others, like Vasuki, are renowned for virtues such as chastity, loyalty, humility, compassion, and deep inner contentment. Their intense spiritual penances along with familial duties characterized their resolve to attain the ultimate Truth. Each was a shining gem in her own right.

Traditional accounts record that many women in ancient days enjoyed a high level of autonomy to undertake spiritual pursuits. Girls often had the freedom to choose their husband, based on their own temperament and life goals. We see this in the life of Devahuti, who sought marriage to a serious seeker, as she wished for a spiritually fulfilling life. These saints did not care about being “equal to men;” their goal was simply to be the best possible version of themselves, which naturally placed them intellectually and spiritually on par with any great sage or devotee. Gargi debated with distinguished male rishis, while Arundhati held a prominent place alongside the Saptarishis (seven sages). Sacred literature recounts many great women who composed Vedic hymns and attained the rank of rishika and mantra drashta.

Countless less-known women seers have been pillars of strength for their husbands and the reason for their noble children’s success. Like Auvaiyar, other spiritual giants have eschewed marriage and dedicated themselves to the service of God and people. Women are an integral part of society, and India is proud to have nurtured such empowered saints and seers who have proved their excellence in virtue, devotion to God and myriad other ways.

Arundhati, Vedic Sage

Daughter of Devahuti and Kardama Prajapati, and the granddaughter of Svayambhuva Manu and Shatarupa, Arundhati was a shining example of devotion, grace and nobility from childhood. Vedic and Puranic incidents demonstrate that she was as great as her mother in many ways, a woman of extraordinary spiritual dedication and wifely perfection.

There are various narratives about her birth. Her story is found in the Siva Purana and Bhagavata Purana. Still revered as an inspirational figure in post-Puranic Sanskrit and Hindi literature, she is featured in Valmiki’s

Ramayana as well as Sant Tulsidas’s Shri Ramcharitmanas, given her husband’s key role in the Ramayana epic. Her meetings with Rama and Sita are especially noteworthy. Arundhati was the great-grandmother of Veda Vyasa, the legendary author of the Mahabharata epic. Vyasa is the archetypal guru to whom the annual Guru Purnima festival is dedicated. Arundhati is believed to be present amongst us even today in the form of a glittering star in the night sky.

Spiritual Upbringing

Growing up in her parents’ hermitage, our luminary was trained in life skills, discipline, social grace and etiquette, building the foundation for her spiritual achievements later in life. Legends say she was groomed by the universal mothers Savitri, Saraswati and Sandhya, whom Arundhati served with humility and sincerity.

Once she was old enough to marry, the perfect groom for her was sought. This was none other than Vasishta Maharishi, one of the greatest Brahmarishis. He is famous for having been blessed with the divine cow Kamadhenu and her calf Nandini, two bovines who could grant any wish to their owners.

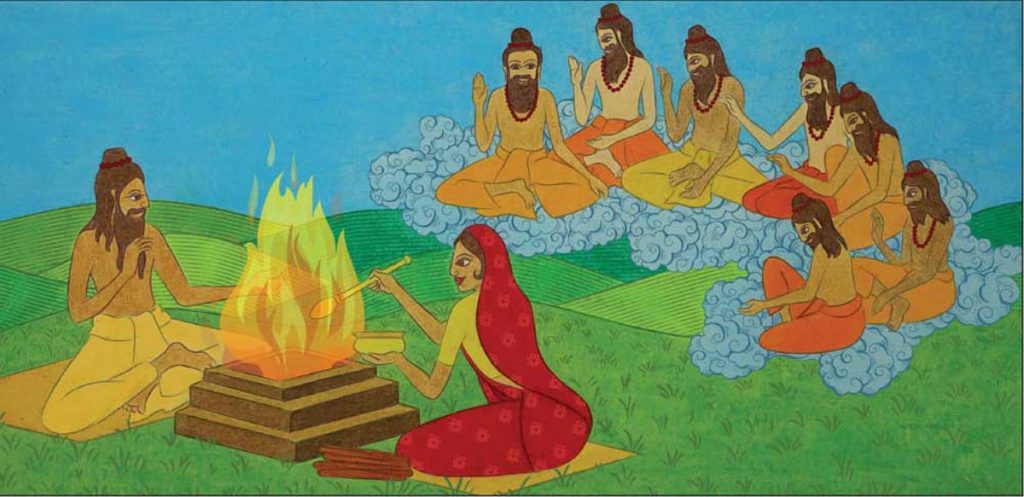

Arundhati and Vasishta were an ideal couple in following a dharmic life, complementing each other in every respect, even performing spiritual penance (tapas) together. Arundhati, possessing the same serene composure as her husband, was respected and worshiped on par with the seven seers (Saptarishis). Indeed, the Mahabharata describes her as an ascetic who gave lofty discourses to these transcendent sages. In due course, Vasishta became the spiritual master of the Ikshvaaku dynasty, to which King Dasharatha and his divine sons—Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna—belonged. This meant that Vasishta and Arundhati were prostrated to by Lord Rama himself!

One of the stories in the Puranas goes thus: One day, Vasishta needed water for his daily rituals and requested Arundhati to fetch some from the river nearby. Arundhati took a pot to the river, and, lo, behold, three devatas—Indra, Agni and Surya—appeared before her! She bowed to them in reverence and continued her duty of fetching water without a second glance. Surprised, the Divinities asked how she could remain so focused in their presence. She replied that serving her husband was like serving God, and to her that was more important than anything else in the world. Nothing could distract her attention. This ability to steady the mind and direct focus where one wants, regardless of the whims of the wandering, truant mind, is the goal of many Hindu spiritual practices.

When the three Lords offered to fill the water pot for her, Arundhati smiled knowingly. Despite their best efforts, they could not fill the vessel to the brim. Arundhati alone was suited to the task, using her spiritual powers to bring the water of River Ganga into her pot. Humbled, the Gods blessed her and Vasishta, and disappeared. It is not surprising that even the Vedas hail her as “Rishinam Arundhati,” meaning Arundhati the sage. Today devotees can visit the Vashishta Guha (cave) and the nearby Arundhati Cave, in Uttarakhand, India, located on the banks of the river Ganga enroute from Rishikesh to Devprayag. The ascetic couple are believed to have meditated in these caves.

Holy Texts

The Vedas (literally, knowledge or wisdom), dated around 3,500 years ago, are the earliest literary sources in Hinduism. According to tradition, the Vedas are divinely inspired truths that were heard by the rishis of India. A rishi (from the Sanskrit root drish , to see) is a seer of mantra, or thought, and is also known as a mantra drashta. The Vedic revelations are hence referred to as shruti , or “that which is heard,” as the rishi is simply seeing or hearing what is already there. Vedas are not associated with a single seer, but with numerous sages who discovered them over at least a 1,000-year period.

In Swami Sivananda’s words, “The Vedic rishis were great realized persons who had direct intuitive perception of Brahman or the Truth. They were inspired writers. They built a simple, grand and perfect system of religion and philosophy from which the founders and teachers of all other religions have drawn their inspiration.”

The four Vedas, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, consist of creation hymns, devotional hymns for a good life, and philosophical discussions on the Self and the Divine. Nature is revered in the Vedas, with prayers to Agni (God of fire), Parjanya (God of rain), Ushas (Goddess of dawn) and other Deities of nature. The Vedas also discuss social life, moral teachings and prevention of diseases.

The chanting of Vedic mantras continues today in several contexts. In addition to the mantras chanted by devotees in daily life such as the Gayatri mantra, Vedic hymns are recited by priests in temple ceremonies. They are also chanted during rites of passage, including an infant’s name-giving, first feeding, coming of age, marriage rituals and last rites. Scriptures state that a Hindu ceremony is considered complete only if the couple perform the rituals together, the wife being present along with her husband.

Arundhati in Indian Weddings

In ancient Indian astronomy, the Mizar star is known as Vasishta, and its fainter counterpart next to it, the Alcor star, is known as Arundhati. The Mizar is perhaps the most famous star of the Big Dipper asterism (Saptarishi Mandala). In Western cosmology, this pair of stars in the Big Dipper’s handle is called “the horse and rider”.

Orbiting one another in the Ursa Major constellation, these binary stars are considered in the Indian context to symbolize an ideal couple. In some Hindu communities, priests conducting a wedding ceremony point out the constellation to the newlyweds as a symbol of marital harmony and loyalty. This is one of the key rituals in traditional South Indian Hindu weddings. The husband holds the wife’s hand, and both look towards the Arundhati star in the sky. They take a solemn pledge of commitment in front of the sacred fire and the community of family and friends.

In Indian astronomical terminology, these stars appear in the Saptarishi Mandala (constellation of seven sages). The fact that the stars orbit each other is believed to symbolize equality in the marriage. Since Sage Vasishta was married to Arundhati, he was also called Arundhati Natha, the husband of Arundhati.

Saint Auvaiyar, Illustrious Tamil Poet

I shall offer to you, O Lord, the delicacies four—fresh milk, pure honey, cane sugar with cereals mixed—O elephant-visaged, bright-jeweled Lord of the Universe, if you will enrich me with the triple-treasured Tamil tongue acclaimed by the ancient academies.”

This famous Tamil devotional poem by Auvaiyar (“wise elder woman”) is featured in the book Loving Ganesha by Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami. Auvaiyar was also affectionately known as Auvai. Over the centuries several women have been known as Auvaiyar in Tamil Nadu, as they were torchbearers of the abundant treasures of Tamil literature. Of them, two are renowned.

Auvaiyar I lived towards the end of the Sangam period, around the 2nd century ce. She was a greatly respected poet who had royal patrons, such as the ruler Adiyaman Neduman Anji, and is likened to other Sangam poets such as Kapilar, whose benefactor was chieftain Vel Pari. Her contributions are found in early anthologies of Tamil Sangam literature such as the Akananuru, a collection of 400 love poems, and

Purananuru, 400 poems addressed to benevolent Chera, Chola and Pandya kings on themes of warfare, poverty and public life.

Auvaiyar II lived around the 12th century in the Chola empire (9th to 13th century) during the times of the poets Kambar (author of Kamba Ramayanam) and Ottakoothar. Some legends feature her as an ambassador of peace between warring kingdoms. She composed famous children’s poems such as Aathichudi, Kondrai Vendan, Nalvazhi, Moodurai, as well as devotional hymns such as the Vinayagar Agaval , appealing to kings and lay people of all ages, even today. This is the Auvaiyar whose inspirational life and contributions we celebrate here.

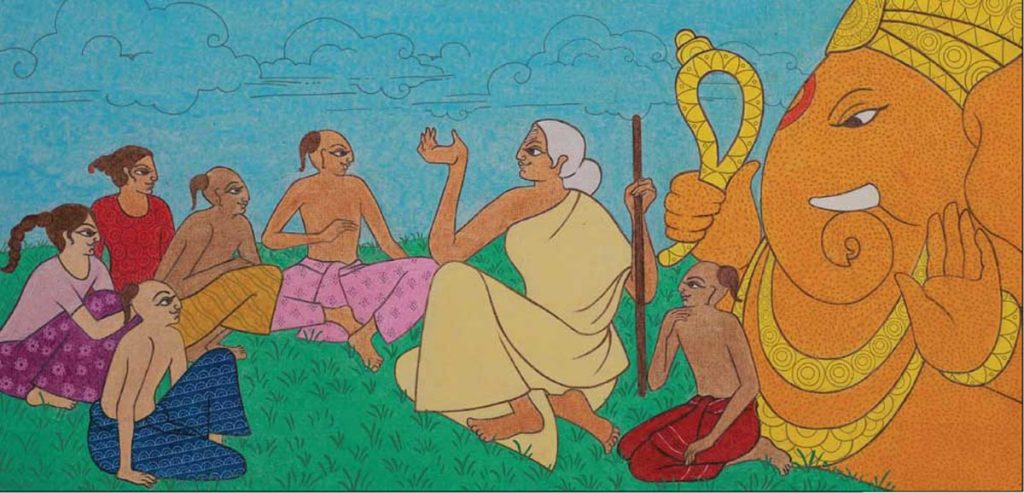

Raised by a wandering minstrel family of Pannars, Auvai displayed an aptitude for religion and literary pursuits at an early age. She grew up to become an intelligent and strikingly beautiful young woman, whom many aristocratic suitors wanted to wed. At an age when most girls prize youth and beauty, our Saivite poet-saint wept and prayed to her chosen Deity, Lord Vigneshvara, to make her body old. Her only interest was in a life of service to Lord Siva and society, and she saw the removal of her youth and beauty as the only way to avoid the unwanted duties of marriage. The young poet knew she could impart wisdom better with a mature and experienced body and mind.

Hearing her fervent prayer, Lord Vigneshvara (Ganesha) granted the wish: her hair became gray, her skin wrinkled and her eyes sunken. Thus was “born” Auvaiyar, in the form she is known and loved. She never married, but became a grandmother to all children through her writings.

Hymn of Praise to Lord Ganesha

Famous among Auvaiyar’s many beautiful devotional songs, “Vinayagar Agaval” is a soulful hymn to Lord Ganesha, sung in a trance towards the end of her life. Considered her sacred masterpiece, it remains one of the most accessible Tamil literary compositions of the period. Shortly before composing the hymn, she had a vision of Ganesha, who promised her that upon leaving her mortal form, she would be taken to Mount Kailasa, the divine abode of Lord Siva. The 72-line Agaval is a form of blank verse that begins with a contemplation on Ganesha’s majestic form and continues as an outpouring of gratitude to the Divine. The hymn is to this day sung throughout Tamil Nadu, especially during Ganesha Chaturthi celebrations.

Ratna Ma Navaratnam describes Auvaiyar’s approach to her beloved Lord in Om Ganesha: the Peace of God: Auvaiyar “views Him enjoying the triple delicious fruits and is amazed at the incongruity of Pillaiyar’s riding on His rat mount! It reminds her that life is a bundle of contradictions and contrasts. The massive elephant with His immense strength and prudence is no more important than the humble mouse.”

Inculcating Values in Children

Auvaiyar’s Aathichudi is an alphabet rhyme for children consisting of 109 single-line proverbs. In these, Auvai offers insightful guidelines for life expressed in simple yet powerful words that are easy for children to grasp as they learn the Tamil alphabet. Advocating moral values, good habits and discipline, Auvaiyar’s Aathichudi and Kondrai Vendan have long been a part of the Tamil language curriculum in schools in Tamil Nadu, India, as well as in Sri Lanka and Singapore, where Tamil is an official language. Auvai’s sayings are learned and recited by children beginning in the first grade to build their vocabulary and memory skills.

Our poet’s influence doesn’t end with children; her proverbs are a part of daily conversation in the most elite circles. Her poignant words were quoted in the Singapore Parliamentary debates on October 17, 2011, when Mr. Vikram Nair recited the proverb Kattradu Kai Mann Alavu Kallathathu Ulagalavu, meaning, “What we have learned is equal to a handful of mud; what we are yet to learn is as vast as the Earth.” Another translation is exhibited at NASA to inspire employees.

Auvaiyar’s Legacy

Blessed with the vision of the Divine, Auvaiyar is considered the wisest woman of all ages throughout Indian culture. In 1991, a crater on Venus was named the Avviyar Crater by the International Astronomical Union. (All craters on Venus are named after historic women, or are given a female first name.) The Auvaiyar statue at Chennai’s Marina beachfront is a famous landmark, standing alongside statues of Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, Sage Tiruvalluvar, Bharathiar and Kannagi. The annual Avvai Vizha, organized by the government of Tamil Nadu, commemorates the poet’s contributions to Tamil literature. Community leaders and Tamil scholars come together to discuss the wisdom poems of this beloved poet-saint.

LEARN MORE

• Watch a famous musical dialogue between Auvaiyar and Murugan from the 1967 film “Kanthan Karunai,” “By the Mercy of Kanthan” (with English subtitles): bit.ly/Auvaiyar-Muruga-Movie

• Enjoy Aathichudi as a children’s rhyme (in Tamil) at bit.ly/AuvaiyarKidsRhyme

• Hear Vinayagar Agaval by Seerkazhi Govindarajan: bit.ly/VinayagarAgavalSung

From Auvaiyar’s Aathichudi, a Rhyme for Teaching the Tamil Alphabet to Kids

அ (a அறம் செய்ய விரும்பு Desire to fulfill dharma

ஆ (ā) ஆறுவது சினம் Cool off anger

இ (i) இயல்வது கரவேல் Give as much as you can

ஈ (ī) ஈவது விலக்கேல் Do not avoid charitable deeds

உ (u) உடையது விளம்பேல் Do not brag about your possessions

ஊ (ū) ஊக்கமது கைவிடேல் Never lose motivation

எ (e) எண் எழுத்து இகழேல் Do not despise mathematics and writing

ஏ (ē) ஏற்பது இகழ்ச்சி Begging is disgraceful

ஐ (ai) ஐயமிட்டு உண் Share with the poor before you eat

ஒ (o) ஒப்புரவு ஒழுகு Live in harmony with the world

ஓ (ō) ஓதுவது ஒழியேல் Never stop learning

ஒள (au) ஒளவியம் பேசேல் Speak not with envy.

அஃ (ak) அஃகம் சுருக்கேல் Do not shortchange others.

Devahuti, Sincere Spiritual Seeker

An exemplary daughter, wife and mother, Devahuti dynamically pursued the path outlined by the

Vedas throughout her life. The Hindu scriptures remind us that every human being should cultivate and focus on the inner desire to realize the Self. Devahuti was one such sincere spiritual aspirant. She chose not to waste her life in trivial pursuits or sensory desires, but opted for liberation, as evidenced by her every decision.

Early Years

Devahuti was one of the adored daughters of Shatarupa and Svayambhuva Manu, “Emperor of the Universe,” as outlined in the Siva Purana and Bhagavata Purana. The Brahma Purana hails Shatarupa as the first woman to be created by Brahma, along with Manu. The Sanskrit word for “human being” is manava, meaning “of Manu;” in other words, we are all the descendants of Manu.

Despite growing up in an affluent family, Devahuti was spiritually mature and mentally detached from a materialistic lifestyle from an early age. She was a living example of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami’s words, “This physical world, though necessary to our evolution, is the embodiment of impermanence, of constant change. Thus, we take care not to become overly attached to it.” Her mind never swerved from devotion towards Lord Vishnu and liberation.

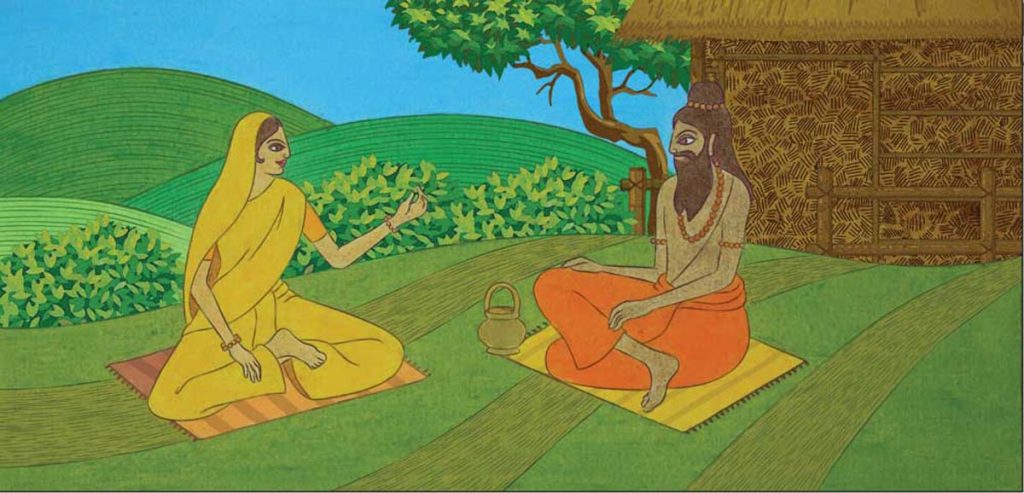

Upon reaching marriageable age, Devahuti envisioned an equally spiritual husband to grow with on the path of wisdom. Sage Narada advised her parents to have her marry Kardama, an ascetic engaged in severe penance, but who would soon embrace family life. Hearing of Kardama’s intense spiritual activities, Devahuti felt certain he was her ideal husband. Manu took Devahuti to Kardama Rishi and expressed his daughter’s wish to marry him. Kardama agreed, and the two were soon wed in a simple ceremony.

Manu and Shatarupa left their princess daughter in the forest with Kardama. Years went by, and Kardama’s austerities continued. As the young couple grew older, Kardama grew oblivious of Devahuti’s presence. Meanwhile, Devahuti continued to fulfill all her wifely responsibilities. She realized the importance of his spiritual life and never once demanded more of her husband, never once drew him away from his spiritual work.

One day, Kardama Rishi opened his eyes after a period of penance and looked at Devahuti in amazement. He expressed gratitude, and openly acknowledged her selfless service and unconditional love: “My dear wife, you are an exceptional woman, and more of an ascetic than I am! Please tell me what I can do for you in return.” Devahuti graciously replied that it was her duty to take care of her husband, especially when he was engaged in profound penance, and that she needed nothing in return.

Touched by her response, Kardama created a beautiful palace with his yogic powers. Thereafter, the couple lived in luxury and were blessed with ten gifted children; nine daughters—named Kala, Anasuya, Shraddha, Havirbhu, Gati, Kriya, Kyati, Arundhati, Shanti—and a son named Kapila Vasudeva. The daughters grew up to be great Vedic women in their own right, and Kapila, believed to be an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, became a renowned sage. Devahuti’s accomplished daughters, like their mother, married great rishis: Kala to Marichi, Anasuya to Atri, Shraddha to Angiras, Havirbhu to Pulastya, Gati to Pulaha, Kriya to Kradhu, Kyati to Brigu, Arundhati to Vasishta, and Shanti to Atharvana.

Devahuti’s Daughters

Anasuya (meaning “devoid of envy”) was the celebrated wife of Sage Atri. Like her husband, Anasuya engaged in penance. Once, using her spiritual powers she reinvigorated a forest. Severe drought had befallen the ancient sanctuary of nature. All the flora was destroyed, animals died and birds migrated to far-away lands. Even the sages were worried. Anasuya, with her meditative powers, brought heavy rains. Life in the forest was restored to its initial glory and she gained renown in the three worlds.

Kyati, another daughter of Devahuti, was married to Sage Brigu, mentor of the asuras (demons), whose cruel follies she overlooked like a kind mother. Maha Vishnu was once after the asuras. When Vishnu asked if the demons had come to Kyati’s hermitage, Kyati lied out of love for and loyalty towards the asuras. Vishnu then destroyed her as well as the asuras she protected. The infuriated Sage Brigu cursed Maha Vishnu that he, too, like Brigu, would be separated from his wife, Goddess Lakshmi. Lord Vishnu honored Sage Brigu’s pain by accepting the curse. Thus, when Maha Vishnu incarnated as Rama, Sita was abducted by Ravana and Rama suffered the pangs of separation from his wife.

Kapila Muni, Devahuti’s Son and Preceptor

Upon reaching his elder years, Kardama Rishi resolved it was time to fully embrace renunciate life. He was content that he and Devahuti had led a meaningful life and fulfilled their responsibilities. Leaving Devahuti with their son Kapila, Kardama retired into the forest in search of ultimate Truth. Devahuti was no less committed to seeking the highest; she too wanted to renounce the world of material pleasures. Regarding her son Kapila as Lord Vishnu incarnate, she accepted him as her guru. Kapila Muni taught his mother the nuances of Sankhya, one of the six classical systems of Hindu philosophy. He expounded spiritual wisdom about the reincarnation cycle of individual souls and explained the paths to liberation, namely bhakti, jnana, karma, and sankhya, emphasizing unconditional surrender. Having practiced all the teachings, Devahuti’s body, mind and soul merged in complete harmony and she lived the last years of her life abiding in the Self. The great Vedic woman Devahuti attained samadhi and consciously left her physical body behind and merged with the Ultimate, thus fulfilling her life’s purpose.

TO LEARN MORE

• Explore: the history and importance of Matrugaya at

www.matrugaya.com

• Plan Your Visit: to Matrugaya in Siddhpur by reading this traveler’s blog:

bit.ly/IndiaYatraBlog2

Matrugaya, where Devahuti Attained Liberation

Matrugaya Kshetra in Siddhpur, near Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, is a pilgrimage site where Devahuti is said to have attained liberation following the teachings of her son, Kapila Mahamuni. It is revered as an auspicious place to perform last rites for one’s mother to help her attain moksha. Thousands of Hindus perform such antyeshti rites at this holy site each year.

Matrugaya is home to Bindu Sarovar, one of India’s five most ancient and holy lakes—the other four being Manasa Sarovar in Tibet, Pushkar Sarovar in Rajasthan, Narayan Sarovar in Kutch, Gujarat, and Pampa Sarovar near Hampi in Karnataka.

Tradition says that it was at the banks of Bindu Sarovar that Kardama Rishi and Devahuti were married and did penance for several years. Here also their son, Sage Kapila, had his ashram and taught the ultimate knowledge of Sankhya philosophy to his mother. Having attained the highest spiritual wisdom, Devahuti is believed to have taken on the form of water (jal svarup), and thus the lake became the holy Bindu Sarovar, where devotees bathe before performing rites for their ancestors.

It is believed that Lord Parshuram performed Matru Shradh at the Bindu Sarovar. There is a temple for him here, alongside the temples of Sri Kapila Mahamuni, Sage Kardama and Devahuti, where their hermitages used to be.

Around the 11th century, Siddhpur was at the height of its glory under the Chalukya dynasty. The Chalukya raja Jayasimha Siddharaja built his capital here. He also built the Rudra Mahalaya, a magnificent temple for Lord Siva. Now in ruins, it was an architectural feat with a three-storied central sanctum tower, 1,600 pillars and 12 entrances. Eleven shrines for Rudra stood around the temple. Today the city is home to the ancient Arvadeswar Shiva Temple, sacred to the Natha Sampradaya.

Gargi, Renowned Philosopher

Gargi was an ancient Indian philosopher and illustrious Brahmavadini, a woman ascetic who was deeply knowledgeable about Brahman and pursued Absolute Truth, the goal of all Hindu spiritual practices. Hailing from the lineage of Garga, and as the daughter of Sage Vachaknu, she was first known as Vachaknavi, and later as Gargi. Historians surmise she lived around the eighth or seventh century bce. She showed great skill in the study of the Vedas from a young age and possessed the acumen and confidence to sit in equality with renowned scholars in royal courts for scholarly debates. Brahmavadini Gargi is famous for her dialogue about the nature of reality with the Advaita philosopher Yajnavalkya, as presented in the sixth and eighth sections of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

Let the Debate Begin

King Janaka, ruler of the Videha kingdom and a distinguished scholar, once organized an assembly of scholars in his court. During this assembly, a grand debate was to take place, and numerous intellectuals were invited. The invitees included the accomplished sage Yajnavalkya. The king offered a thousand cows to the most erudite of them all. Immediately Yajnavalkya asked his disciple to take possession of the cows on his behalf. The others were angered by his audacity to claim victory without a single argument. Challenges over the coming days came from eight illumined sages. One by one, they debated with him and were defeated, as he successfully answered their most onerous philosophical questions.

Gargi, the only female scholar in the gathering, equaled all others in intelligence, poise and knowledge. When it was her turn to face the sage, she was keen and relentless, presenting trenchant questions about quintessential knowledge and the nature of the universe. These queries served as a springboard for their debate, which soon turned to a discussion of atma, the omnipresent soul.

Gargi more than proved her profound wisdom in the way she carried the metaphysical duel with the sage. When even she was defeated in debate, she praised Yajnavalkya for his depth and mastery of knowledge, and proclaimed to the entire assembly that no one could ever defeat him in a discussion about the soul. It takes a great philosopher to know one! Yajnavalkya was glad to be appreciated by the erudite Gargi. Because of her skill, she was honored as one of the Navaratnas (nine precious gems) in King Janaka’s court.

Here are excerpts from their exchange (translation from Swami Sivananda’s Essence of Principal Upanishads ).

“Gargi said: O Yajnavalkya, that of which they say it is above the heavens, beneath the earth, embracing heaven and earth, past, present and future, tell me in what is it woven like warp and woof?

“Yajnavalkya replied: In ether (akasha).

“Gargi said: In what then is the ether woven, like warp and woof?

“Yajnavalkya said: O Gargi, the

Brahmanas call this Akshara (the Imperishable). It is neither coarse nor subtle, neither short nor long, neither red nor white; it is not shadow, not darkness, not air, not ether, without adhesion, without smell, without eyes, without ears, without speech, without mind, without light, without breath, without a mouth or door, without measure, having no within and no without. It does not consume anything; nor does anyone consume it.

“By the command of that Indestructible Being, the Sun and the Moon stand apart. By the command of that Being, heaven and earth stand upheld in their places. By the command of that Being, minutes, hours, days and nights, half-months, months, seasons, years all stand apart.

“By the command of that Being, some rivers flow to the east from the snowy mountains, others to the west, and others to the quarters ordained for them.”

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

As one of the 13 mukhya (principal) Upanishads , the Brihadaranyaka is important in many schools of Hindu thought. Part of the Shukla Yajur Veda , it is estimated to have been composed between 900 and 600 bce. It is a treatise on atman (Self or Soul) and covers metaphysics, ethics, karma and a yearning for knowledge. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is known for the major philosophical conversations that make up the core of its teachings. Two particularly famous dialogs are those between Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi and between Yajnavalkya and Gargi. Adi Shankaracharya, Ramanujacharya and Madhvacharya, founders of the three major schools of Vedanta, have written extensive commentaries (bhasya) on this Upanishad, which are widely studied by students of Hindu philosophy.

Did you know that the Pavamana Mantra is from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (1.3.28)? This is a popular shanti (peace) invocation that is chanted at prayer gatherings.

असतो मा सद्गमय।

asato mā sadgamaya

तमसो मा ज्योतिर्गमय।

tamaso mā jyotirgamaya

मृत्योर्मा अमृतं गमय।

mṛtyormā amṛtaṁ gamaya

From untruth, lead us to truth.

From darkness, lead us to light.

From death, lead us to immortality.

The Vedic Age

The Vedas are Hinduism’s earliest literary sources. The Rig Veda, the oldest of the compendium, is reckoned by 19th-century Western Indologists to have been composed around 1,500 bce, a date that began a 1,000-year period known as the Vedic Age. This dating, which is closely bound to the now largely debunked Aryan Invasion Theory, proposed and settled upon before the discovery of the Indus Valley civilization, is contested by many Indian historians. Using astronomical references found in the Vedic texts and other advanced dating methods, they place the

Vedas as far back as 4,000 bce.

Upanishad Ganga Teleserial

Episode 30 of the teleseries Upanishad Ganga, entitled “The Existence Principle,” dramatically depicts the awe-inspiring story of Yajnavalkya and Gargi, in which Gargi challenges Yajnavalkya with several questions. Upanishad Ganga is a popular Hindi television series of 52 episodes, 30 minutes each, that present ancient Vedic culture and Upanishadic wisdom. Originally premiered in 2012 as a “Chinmaya Creations” project, the concept was the brainchild of Swami Tejomayananda of the global spiritual organization Chinmaya Mission. The series was televised on Doordarshan, a channel founded by the Indian government. Upanishad Ganga episodes unravel spiritual concepts such as the human goals of life (dharma, artha, kama and moksha), life’s stages (studentship, married life, retirement and renunciation), types of yoga (karma yoga, bhakti yoga, and jnana yoga), the theory of creation, birth and rebirth, the primordial Om, and guru.

It expounds on these topics through stories of great Hindu saints and thinkers such as Valmiki, Harishchandra, Chanakya, Tulsidas, Mirabai, Arunagirinathar, Bhadrachala Ramadas and Veda Vyasa. Replete with songs and chants, the series provides a family-friendly way of learning Hindu spirituality. The complete series, with English subtitles, is available as a set of 12 DVDs in Chinmaya Mission web stores and from online providers such as Amazon and Flipkart. The set includes relevant Sanskrit verses with English transliteration and translation, and resources for further reflection on the concepts from each episode.

Women in the Vedas

By Nirmal Laungani

More than 30 of the Vedic rishis were women. Married and single women alike were acknowledged authorities on the Vedic wisdom. Gargi debated with Sage Yajnavalkya on the origin of existence. Other Vedic hymns are attributed to Vishvavara, Sikta and others. The Rig Veda identifies many women rishis; indeed, it contains dozens of verses accredited to the woman philosopher Ghosha and to the great Maitreyi, who rejected half her husband Yajnavalkya’s wealth in favor of spiritual knowledge. It also contains long philosophical conversations between the sage Agastya and his highly educated wife Lopamudra.

Rig Veda clearly proclaims that women should be given the lead in ruling the nation and society, and that they should have the same right as sons over the father’s property. “The entire world of noble people bows to the glory of the glorious woman so that she enlightens us with knowledge and foresight. She is the leader of society and provides knowledge to everyone. She is symbol of prosperity and daughter of brilliance. May we respect her so that she destroys the tendencies of evil and hatred from the society.” (1.48.8)

Atharva Veda states that women should be valiant, scholarly, prosperous, intelligent and knowledgeable; they should take part in the legislative chambers and be the protectors of family and society. When a bride enters a family through marriage, she is to “rule there along with her husband, as a queen, over the other members of the family.” (14.1.43-44)

Yajur Veda tells us, “The scholarly woman purifies our lives with her intellect. Through her actions, she purifies our actions. Through her knowledge and action, she promotes virtue and efficient management of society.” (20.84)

Ghosha, Vedic Seer

Ghosha was a great ascetic rishika and mantra darshini, a seer who brought through Vedic chants. She was the daughter and student of Sage Kakshivan and granddaughter of Rishi Dirghatamas, who coined the oft-repeated Sanskrit aphorism “Ekam Sat Vipra Bahudha Vadanti” (That which exists is One; the sages call It by various names), which appears in Rig Veda 1.164.46. Dirghatamas was the chief priest of King Bharata, according to the Aitareya Brahmana of the Rig Veda. King Bharata, the illustrious son of Shakuntala and Dushyanta, unified all of India under one rule. One of the earliest rulers, it was he after whom India was named Bharata Varsha. Ghosha’s son Suhstya also contributed to the Rig Veda. Thus, this family of seers is responsible for numerous Vedic hymns we enjoy to this day.

As a young lady, Ghosha was afflicted with ill health, and her marriage was annulled. She worshiped the Ashwini Kumaras in two hymns, praying for abundance, virtue and release from disease and misfortune. Over time, her health, beauty and youthfulness were restored. The Ashwinis (twin brothers) are Vedic Gods of ayurvedic medicine, physicians to the devas. They are invoked several times in the Rig Veda , depicted as youthful men with horse faces.

Ghosha’s two hymns to the Ashwinis appear in the tenth book of the

Rig Veda as suktas 10.39 and 40, each consisting of fourteen verses. The prayers glorify the twin healers while invoking abundance and prosperity. Ghosha’s words glow with a noble woman’s refinement and commitment to the path of knowledge. Sri Krishnapremi Swamigal offers a summary of her hymns in his Sati Vijayam: (translation by Smt. Vishakha Hari).

“Hey Ashwini Kumaras! Because of your mercy, this Ghosha has become highly blessed. Now she is going to get married. May her husband be a great farmer. Let there be adequate rains wherever he dwells. Let his cultivation be fruitful. Let him not have any enemies. Bless him that he should be handsome and youthful and that this Ghosha should lead a happy life.

“Hey Ashwini Kumaras! Just as a father teaches and guides his children, show me the true path of knowledge. Guide me in the spiritual path as well. I am helpless, and you should save me from going astray. I should live a great life and beget many children and grandchildren. Grant me the blessing that every moment I should be lovable to my husband.”

In his Vedic Experience, an Anthology of the Vedas for Modern Man and Contemporary Celebration, Raimundo Panikkar describes Ghosha’s Vedic-Age perspective toward health and disease: “Human malady is not a trifling matter, and here there is no room for lofty considerations, nor is there a way of escape. Man is totally engaged in his existential struggle for well-being and he is facing the dire reality of a power that seems to rob him of his health and even of his life. Yet he is determined to face the menace, to struggle, and in the end to win. He has in his hand a medicinal herb, on his lips a sacred mantra, in his heart a burning hope, and in his mind an unflinching faith. He is well aware of the complex web of relations which crisscrosses the whole of reality and he intends to intervene in order to restore the lost harmony and balance.”

Ghosha’s suktas highlight the necessity to lead a righteous and spiritual life, a theme echoed throughout the Vedas.

LEARN MORE

• Read Raimundo Panikkar’s Vedic Experience for English translations of, and commentary on, Vedic hymns and other sacred texts: bit.ly/VedicExperience

• Watch Part 1 of “History of Hindu India” documentary: bit.ly/2piE84n

• Enjoy a video on Vedic Ritual Practice, with recitation of the Vedas, produced by Times Living: bit.ly/VedicPractice

Quotes on Vedic Wisdom

“Karma is not fate, for man acts with free will, creating his own destiny. The Vedas tell us if we sow goodness, we will reap goodness; if we sow evil, we will reap evil. Karma refers to the totality of our actions and their concomitant reactions in this and previous lives, all of which determines our future.” Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

“By the Vedas no books are meant. They mean the accumulated treasury of spiritual laws discovered by different persons in different times. Just as the law of gravitation existed before its discovery, and would exist if all humanity forgot it, so is it with the laws that govern the spiritual world.” Swami Vivekananda

“The Hindus have received their religion through revelation, the Vedas. These are direct intuitional revelations and are held to be apaurusheya, or entirely superhuman, without any author in particular. The Veda is the glorious pride of the Hindus, nay, of the whole world!” Swami Sivananda

“All ancient Hindu Vedic gods are but functional names of the One Supreme Power, manifesting in myriad forms.” Swami Chinmayananda

“The Vedas are not authored by any individual, nor even by a group of rishis, or seers. Vedanta is Knowledge that is revealed by the Lord Himself.” Swami Tejomayananda

“Vedas are simply downloaded information. The rishis went into deep meditation, and what they saw and heard they started sharing.” Sri Sri Ravi Shankar

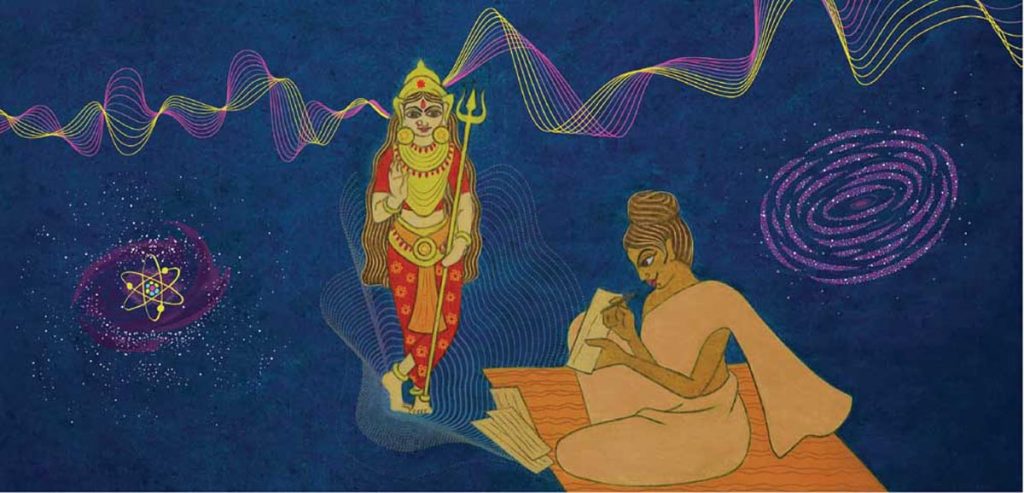

Vakdevi, Vedic Poet

Vakdevi, the daughter of Rishi Ambhruna, had a spiritual bent of mind right from childhood. Given her father’s name, she was also known as Vagambhruni. Vakdevi was a mantra drashta (seer) who composed the popular Devi Suktam, also known as the Ambhruni Suktam or Vak Suktam, consisting of eight stanzas in praise of the Mother Goddess. It is the 125th hymn in the 10th mandala of the Rig Veda, Hinduism’s earliest literary scripture.

Through advanced sadhana (spiritual austerities), Vakdevi reached a level of spiritual maturity that allowed her to identify with the Divine. She then sang this deeply philosophical hymn in a state in which she was one with the Goddess she propitiates, and then speaks as the Goddess herself. The rishika (sage who composed the hymn) and the Devata (Deity propitiated by the hymn) were one and the same. This is a unique feature of Devi Suktam. Having completely transcended her individuality and ego—a spiritual goal aspired by many through the ages—Vakdevi becomes one with the omnipresent Brahman, entering a state of non-differentiation between man and woman, human and God.

Today the Devi Suktam is chanted throughout the world during the worship of the Goddess in daily temple rituals and sacrificial ceremonies such as homa and havana. It is also chanted at the end of Devi Mahatmyam recitations.

The Vedas

The Vedas are vast anthologies of ancient Sanskrit hymns and chants envisioned by rishis and rishikas, male and female sages, that are recited in an intoned meter. The intoned chanting, with specificities in regard to meter and style, is one of the primary differences between later mantras and Vedic mantras. The cadenced recitation of Vedic verses, with four main tones, sounds almost musical. The Devi Suktam is composed in two different chandas (poetical metrics). Seven verses are in Trishtup Chandas, which has 11 syllables per line, while the second verse is in Jagati Chandas, with 12 syllables per line.

Today, Vedic chanting is popular among nearly every Hindu group worldwide. Vedic schools, called Veda patashalas, are located all across India. These are run in the traditional gurukulam format, in which students live with their teachers at the center and train in Sanskrit studies. The patashalas teach chanting and study of Hindu scriptures, rituals, traditions and religious practices to young men who aspire to be priests or pundits. Two of the largest patashalas are the Veda Agama Samskrutha Maha Patashala, Karnataka, and the Tirupati Temple Patashala in Andhra Pradesh. Some patashalas focus on specific Vedas, such as the Yajur Veda or

Rig Veda. The patashala in Bengaluru also trains students who aspire to become priests in the Saivagama tradition. (See bit.ly/BengaluruPatashalaHToday for an indepth article on this school.)

Vakdevi’s Devi Suktam

Here is Vakdevi’s Devi Suktam, “Hymn of Omniscience,”

Rig Veda 10.125, translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith:

- I travel with the Rudras and the Vasus, with the Adityas and all Gods I wander. I hold aloft both Varuna and Mitra, Indra and Agni, and the Pair of Asvins.

- I cherish and sustain high-swelling Soma, and Tvastar I support, Pusan and Bhaga. I load with wealth the zealous sacrificer who pours the juice and offers his oblation.

- I am the Queen, the gatherer-up of treasures, most thoughtful, first of those who merit worship. Thus Gods have established me in many places with many homes to enter and abide in.

- Through me alone all eat the food that feeds them, each man who sees, breathes, hears the word outspoken. They know it not, but yet they dwell beside me. Hear, one and all, the truth as I declare it.

- I, verily, myself announce and utter the word that Gods and men alike shall welcome. I make the man I love exceeding mighty, make him a sage, a rishi and a Brahman.

- I bend the bow for Rudra that his arrow may strike and slay the hater of devotion. I rouse and order battle for the people, and I have penetrated Earth and Heaven.

- On the world’s summit I bring forth the Father: my home is in the waters, in the ocean. Thence I extend over all existing creatures, and touch even yonder heaven with my forehead.

- I breathe a strong breath, like the wind and tempest, the while I hold together all existence. Beyond this wide earth and beyond the heavens I have become so mighty in my grandeur.

Meaning of the Devi Suktam

According to Sayanacharya, a 14th-century Vedic scholar and Sanskrit grammarian from the Vijayanagara empire, Vakdevi was a Brahmavidushi (one who has realized Brahman) who has eulogized herself in this suktam. The Devi Suktam can thus be thought of as an “atmastuti,” a hymn that glorifies oneself. However, the ‘I’ Vakdevi refers to in her hymn is not the ego-centric ‘I’ that we usually mean in our day-to-day speech. Vakdevi refers to the supreme, eternal, absolute Consciousness, the foundation of both the ego (subject) and the universe (object). One can interpret this suktam as an affirmation by the Goddess (Devi), who expounds on Her own glories and powers. Today, Shaktas may conceptualize Goddess as Adi Parashakti, Vaishnavas think of Her as Mahalakshmi, and Shaivas consider Her Parvati. Vakdevi’s hymn is one of the boldest (and oldest) proclamations of the realization of Advaita (non-dualist) philosophy by any seer in all of the

Vedas .

LEARN MORE

• Learn Vakdevi’s suktam with this YouTube video (lyrics and translation provided): bit.ly/VakdeviSuktam

• Watch/Hear Vedic Pandits chant the Devi Suktam: bit.ly/DeviSuktamChanting

Vedic Chanting in Daily Life

Did you know that the popular Mrtyunjaya Mantra and Gayatri Mantra are Vedic hymns?

Millions of Hindus worldwide chant parts of the Vedas in their daily religious practices. Some schools of Hinduism advocate that everyone should spend some time each day studying and memorizing sections of the

Vedas.

“Aum” is chanted at the beginning and at the end of all Vedic texts, because it is believed this one syllable is the source of creation and encapsulates the entire Vedas. The popular Ganesha invocation, Gananam Tva Ganapatim, is a mantra from the Rig Veda (2.23.1). Several temples perform annual Ati Rudram Mahayagnas where 121 priests chant Sri Rudram many times. 14, 641 times (each round taking about 22 minutes). This remarkable feat takes eleven days!

Other popular Vedic chants include several Shanti Mantras, Ganapati Atharvashirsha Upanishad, Purushasuktam, Narayanasuktam, Medhasuktam, Durgasuktam, Shrisuktam, and Shishya Anushasanam. The famous Purusha Suktam emphasizes the correspondence between the microcosm and the macrocosm. Guy Beck, an American musicologist and historian of religions, discusses this hymn in his work, saying it underscores the idea that the human body and mind correspond to the universe, and one can be experienced in the other. This is the basis of many yogic practices, including those that specifically emphasize sound.

The correspondences between microcosm and macrocosm in Hinduism have remained prominent from the earliest time to the present—for example, seeing the Vedic altar as a symbol of the universal body, seeing God as a human form that fills the universe, seeing the universe as contained within the human body, and experiencing this oneself by practicing yoga.

Vasuki, Perfect Partner

The virtuous Vasuki and her husband, the famed poet-philosopher Tiruvalluvar (or simply Valluvar), are known throughout the Tamil-speaking world. One of the great “power couples” of ancient India, they are held in high esteem for their exemplary family life and their contributions to Tamil literature and Indian society. Scholars debate about the time period they lived in, proposing anywhere between the third century bce and the fifth century ce.

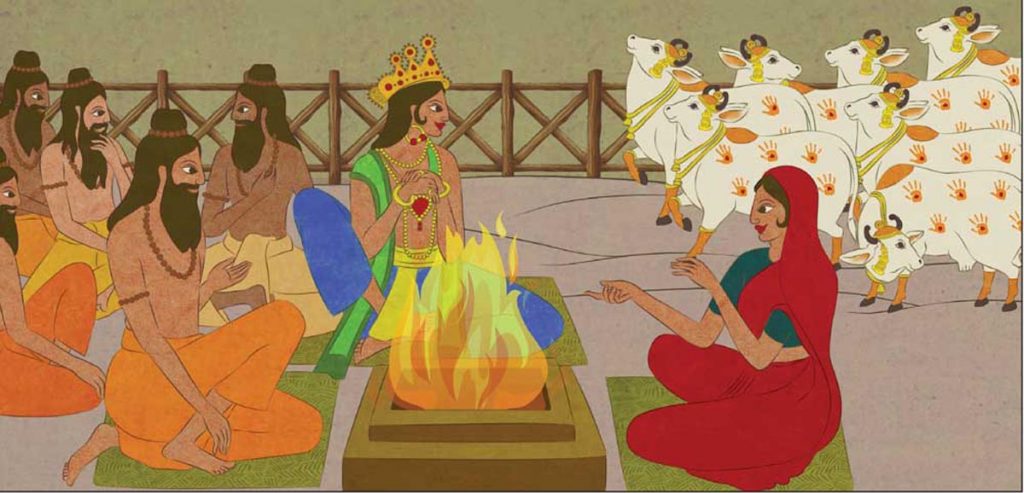

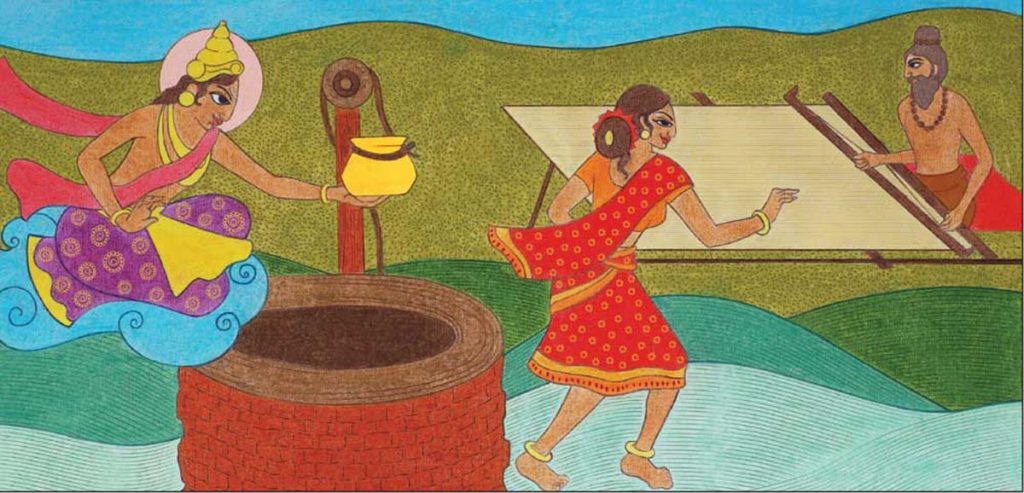

Though difficult to provide hard evidence for incidents that took place so long ago, Vasuki and Tiruvalluvar are believed to have had a strong and beautiful marriage with deep understanding. They were both ideal in their respective roles. All the villagers admired them and sought Tiruvalluvar’s advice on marriage and family life, though he was a simple weaver. Personifying Tiruvalluvar’s Kural 55, “Even the rains will fall at her command who upon rising worships not God, but her husband,” Vasuki considered Tiruvalluvar a living God. Her wifely devotion can be observed in the loving, sincere way she attended to his needs. Many stories demonstrate ways that nature obeyed her command.

One day, Vasuki was drawing water at the well outside their house. Traditional Indian wells (kineru) consist of a pulley system that is mounted at the well and a rope that moves through the pulley. One end of the rope is tied to a bucket which is dropped into the well; the other end is held by the person drawing water. Water is fetched by lowering and raising the bucket.

While Vasuki was pulling up a bucket full of water from the well, Valluvar called out to her. Narratives say that Vasuki did not wait an instant to respond. She abandoned the task with the bucket raised midway, and instantly rushed to her husband. When she came back, the bucket was still suspended midair, exactly where she had left it! Normally, it would have fallen back into the well with the rope, given the weight of the water—but Vasuki’s virtue and devotion miraculously led to defying the law of gravity.

Tiruvalluvar’s Tirukural

Regarded as a Tamil Veda and one of the greatest works in Tamil literature, the Tirukural (“holy couplets”) consists of 1,330 two-line aphorisms, or kurals, that advocate virtue and ethics in daily living. The Tamil word

tiru means holy, while kural means a brief statement or verse. The text is divided into 133 chapters with ten couplets each. The first section, entitled Virtue, has 38 chapters; the second, on the material world (wealth, polity and economy) consists of 70 chapters; and the third section covers love in 25 chapters.

Tiruvalluvar was an intellectual weaver in the Mylapore area of Chennai, Tamil Nadu. He is sometimes considered the 64th Nayanmar (saint) in the Saiva Siddhanta tradition. Western scholars have theorized that he was a Jain. His work covers the entire gamut of human experience, from love and family life, dharma, leadership and management techniques, to life’s highest attainment, Self Realization. His insightful work, highly aphoristic, is often featured in Tamil textbooks for children to enhance memory, advance language skills and imbibe the importance of value-based living.

The Tirukural has been translated into over 80 languages. Several scholarly commentaries have been written over the centuries, each offering its nuanced interpretation. Many monuments have been dedicated to the poet-saint, including a 133-foot-tall stone sculpture on an island near Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu; a park in Chennai with each verse carved in polished black granite; and a life-size granite statue at Kauai Aadheenam in Hawaii.

Vasuki’s Unswerving Dedication

Vasuki and Tiruvalluvar led a long, happy and peaceful life together, with children according to some. As Vasuki was about to leave her mortal form, Valluvar asked if there was anything he could do for her. She answered in the affirmative, and said she had one question, about his habit of keeping a small cup of water and needle by his side during meals since their first day of marriage. He had never used either of these in all those years, though she had dutifully placed them near him every day.

Valluvar replied that they had a purpose, but she never gave him an opportunity to use them. Seeing Vasuki’s puzzled countenance, Tiruvalluvar explained: “Dear wife, you serve me rice every day. If you ever spilled any, I thought I would use the needle to gather it from the floor, wash it in the cup of water, and put it back on my plate. But you never spilled even a single grain of rice! You have been so focused on serving me with full attention that I have never had to use my needle or the cup of water.”

In the words of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami, “The Tamil understanding of the husband-and-wife relationship is vastly different from modern thinking, which stresses sameness and equality. Yet, those who have seen the deepness of such a family and such a marriage would never call it antiquated. The Tamil wife is pure in thought, devoted to her duties, perfect in hospitality to guests. She is frugal, strong and modest, never bold. She adores her husband and never even looks into the eyes of another man. She is, they say, the authoress of her husband’s renown and glory, the support that lifts him high in the eyes of others.”

Subramuniyaswami also taught that we cannot attain liberation until we have properly performed the various dharmas in our many lives. Vasuki surely performed stri dharma to perfection.

The epitome of attentiveness, patience and love, Vasuki is cited as a role model for wives in Tamil Nadu. A home where the couple is likened to Vasuki and Tiruvalluvar is considered truly blessed.

LEARN MORE

• Visit the Tiruvalluvar Temple in the historic Mylapore neighborhood in Chennai, Tamil Nadu

• Read Weaver’s Wisdom: Ancient Precepts for a Perfect Life , an English translation of the Tirukural by Sivaya Subramuniyaswami: bit.ly/WeaversWisdom

Verses from the Tirukural

Sivaya Subramuniyaswami’s Weaver’s Wisdom

Chapter 1, Praising God, KURAL 1

Akara muthala eluth ellam Athi Bhagavan muthatre ulaku.

“A” is the first and source of all the letters. Even so is God Primordial the first and source of all the world.

Chapter 3, The Greatness of Renunciates, KURAL 27

Touch, taste, sight, smell and hearing are the senses—he who controls these five magically controls the world.

Chapter 5, Family Life, KURAL 45

When family life possesses love and virtue, it has found both its essence and fruition.

Chapter 7, The Blessing of Children, KURAL 66

“Sweet are the sounds of the flute and the lute,” say those who have not heard the prattle of their own children.

Chapter 10, Speaking Pleasant Words, KURAL 92

Better than a gift given with a joyous heart are sweet words spoken with a cheerful smile.

Chapter 11, Gratitude, KURAL 108

It is improper to ever forget a kindness, but good to forget at once an injury received.

Chapter 14, Possession of Virtuous Conduct, KURAL 140

Those who cannot live in harmony with the world, though they have learned many things, are still ignorant.

Chapter 20, Avoidance of Pointless Speech, KURAL 200

In your speaking, say only that which is purposeful. Never utter words that lack purpose.

Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian is a Los Angeles based vocalist-scholar who brings devotional singing, scholarship and storytelling onto one platform. With an M.A. in Religious Studies from Stanford University, she writes on the great Indian poet-saints of the Bhakti Movement and serves as a Hindu speaker on interfaith forums. She has recorded several devotional albums with her mother and guru, Padmini Chandrashekar, in her hometown Singapore. Lakshmi performs concerts of Electronic Bhakti Music with her husband Aks (www.eclipse-nirvana.com).

Thank you. Fantastic article by an Indian American young woman! May God bless you & best wishes to you.