Honoring the Life and Philosophy Of India’s Revolutionary Rishi

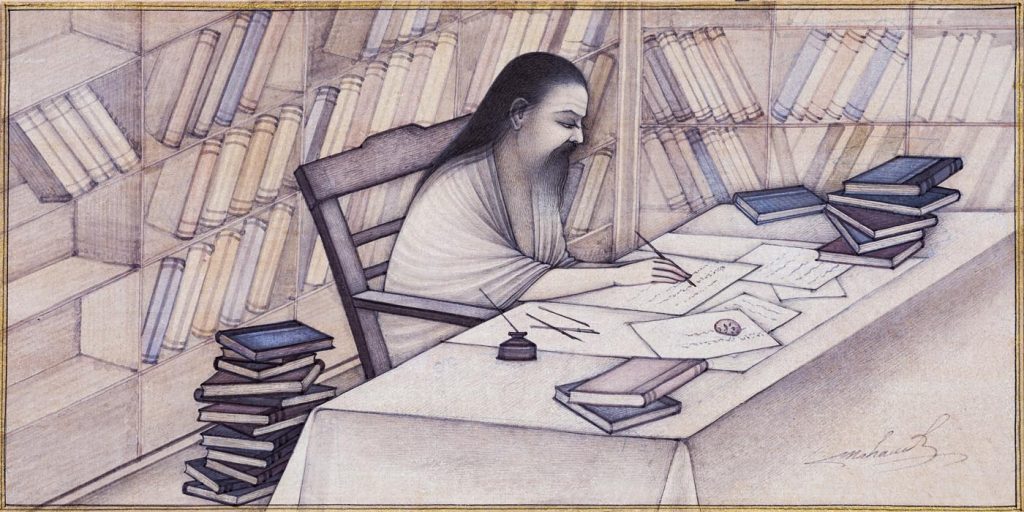

Written by Sudarshan Ramabadran • Art by Mahaveer Swami

As a civilizational nation state with hinduism at its core, India has produced seminal thinkers who have attracted seekers from around the globe. While soft power is in vogue now, these thinkers were ambassadors of the phenomenon. In their time, they drew millions to their teachings, and they do so even today. It would be an understatement to say that they have exercised the most enduring influence over seekers, cutting across ethnicity, creed and religion. This has made them truly universal in thought, word and deed. These thinkers have inculcated in humanity the thought that the world is one family, and its challenges are our own.

The year 2022 witnessed India celebrating the 75th year of independence from colonial rule, and Sri Aurobindo’s 150th birth anniversary. There have been many changes and advancements from the time the British left India until now. One thing has not changed: India’s commitment to the spiritual quest, the unifying thread of our civilizational ethos spanning countless centuries. The state of Bengal has produced more than its share of pivotal minds who have enabled the country’s brethren to prosper intellectually and spiritually. Foremost among them were Ramakrishna Paramahansa, Swami Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore and Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950).

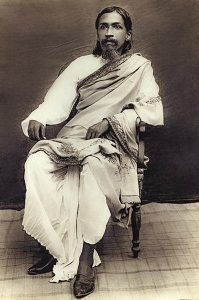

Sri Aurobindo was a multifaceted personality. Educated abroad, he returned to India to become an educationist before joining the revolutionary movement whose goal was to drive the British out of the country. He wrote extensively through his journals and newspapers, embodying true nationalism, then in midlife turned inwards through raja yoga. His life presents a wide array of accomplishments for all to observe, study and use as tools for evolving. Through his writings in the Life Divine and Savitri and concepts such as Integral Yoga, Aurobindo unveiled his spiritual discoveries, which are followed by thousands around the globe today.

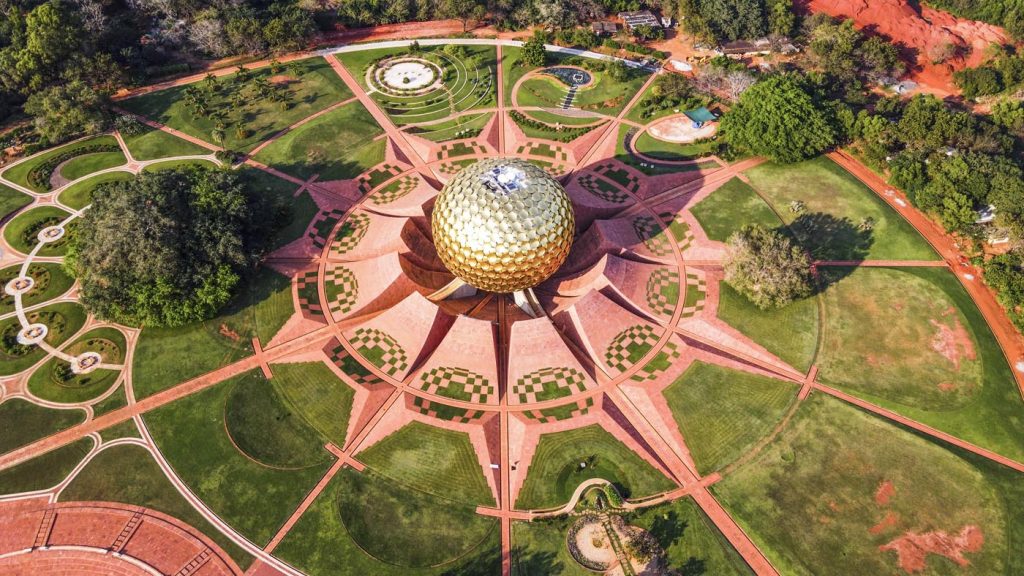

During the 200 nationwide programs organized for the annual G-20 (Group of 20 countries) summit in 2023 by the Government of India, one of the venues of the deliberations was Puducherry, where the delegates visited Auroville and got glimpses into the life of Sri Aurobindo.

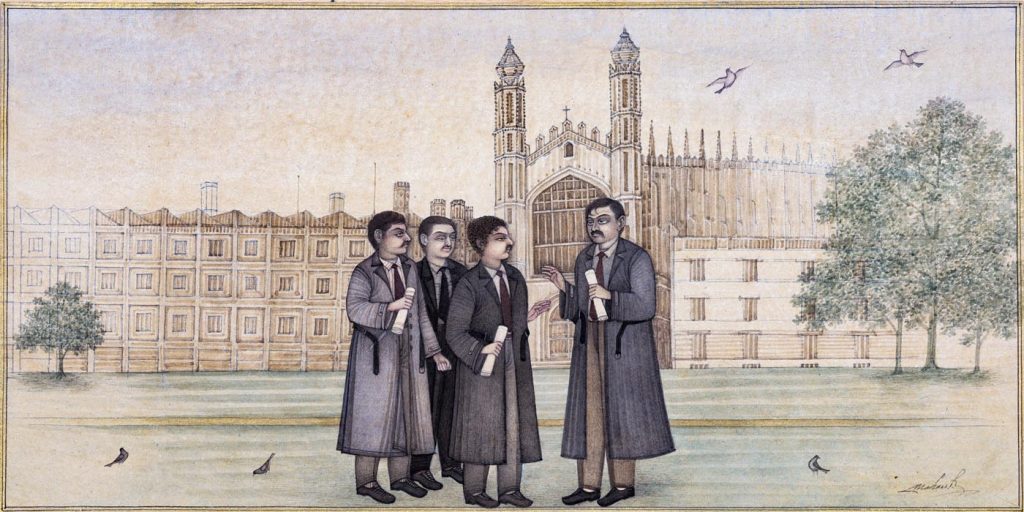

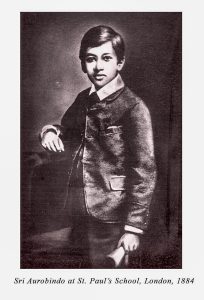

Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta (today’s Kolkata) in India on August 15, 1872, to Dr. Krishnadan Ghosh and Swarnalata Devi. He had two elder siblings, Benoybushan and Manmohan, a younger sister Sarojini and one younger brother Barindra Kumar. According to Sri Aurobindo, A Short Biography by Matthijs Cornelissen, “His father, a thoroughly Anglicized Indian doctor in British Government service, wanted his sons to have a solid, British education, and when Aurobindo was seven, he sent him, together with his two brothers, to England with the specific instruction that the three brothers should be kept free from Indian influence. . . . When he returned to India in 1893, he had an excellent command of English, Greek, Latin and French, and knew enough German and Italian to enjoy Goethe and Dante in the original, but … he knew rather little about India.”

Some accounts say his father played a key role in sensitizing his son’s mind to the struggles and ill treatment of the Indian under colonial rule. Towards this, the youth formed a group of Indians to rebel against the leadership of Dadabhai Naoroji and his moderate or pacifist brand of politics, a political approach that he was against. It is believed that while he was in the UK, a secret society by the name Lotus and Dagger was formed with the intention of overthrowing British rule, but it never acted.

After his extended time in London, Sri Aurobindo moved to Baroda (Vadodara) in West India, where he spent 13 years in state service that included assignments in the settlement and the revenue department. He served as as professor in English and as vice principal and acting principal of the Baroda College, today known as the Maharaja Sayajirao University. He also performed secretarial work for the Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda, which included writing some of the ruler’s speeches and reports. During these years, he mastered several Indian languages including Marathi, Gujarati, Sanskrit and Bengali. Author Vinayak Lohani writes that for Sri Aurobindo the first real discovery of India happened during his days in Baroda. His tryst with Sanskrit happened here, as he immersed himself in reading the works of India’s greatest poets—Valmiki, Kalidasa, Veda Vyasa and so on. Amongst his favorites was Ramayana and its author Valmiki. I have been fortunate to visit the Aurobindo Ashram in Baroda, which houses some of the master’s literature and is open to all for meditation. The calmness of the place is surreal.

Awakening to India’s Plight

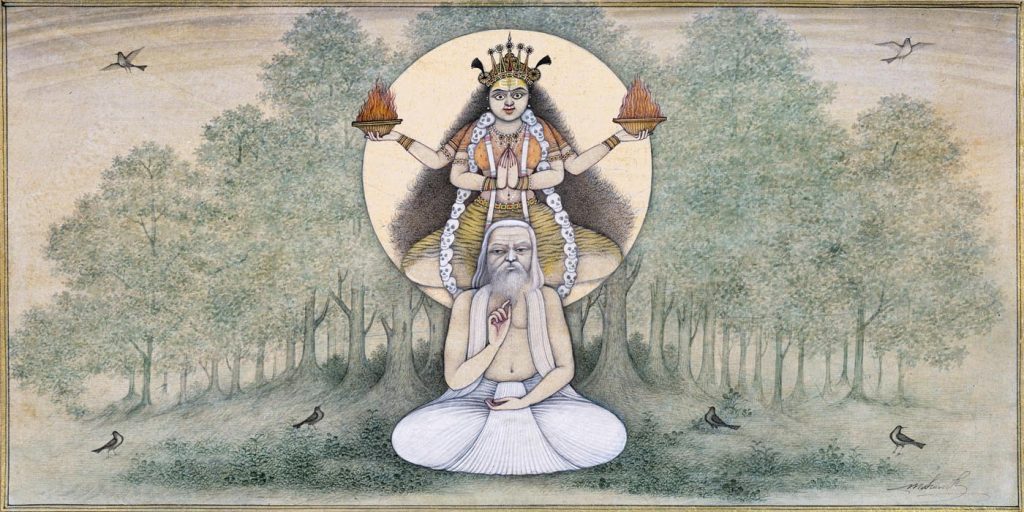

It is reported that sometime in 1905, during a seance guided by Aurobindo’s brother Barin, Ramakrishna Paramahansa called upon Aurobindo to build a temple of selfless workers for the reconstruction of India. This gave rise to the famous Bhawani Mandir pamphlet, a fascinating manifesto in which he referred to Mother India as Bhawani Bharati, Kali, Goddess of strength, whom Ramakrishna Paramahansa worshiped.

Aurobindo defined Bhawani Bharati as infinite energy and more: “In the unending revolutions of the world, as the wheel of the Eternal turns mightily in its courses, the Infinite Energy which streams forth from the Eternal and sets the wheel to work, looms up in the vision of man in various aspects and infinite forms. Each aspect creates and marks an age. Sometimes She is Love, sometimes She is Knowledge, sometimes She is Renunciation, sometimes She is Compassion. This Infinite Energy is Bhawani. She also is Durga, She is Kali, She is Radha the Beloved, She is Lakshmi. She is our Mother and the Creatress of us all.” Aurobindo’s diction was unmatched.

The message was a call to Indians everywhere to work relentlessly for the rebirth of the country. In the manifesto he went on to lay out general rules for those taking up the task of rebuilding the country, such as committing four years of service to this humongous work. Money received by them or through their work and publications would be directed towards the country that was referred to as Mother. There would be no gradations or hierarchies in this work, and the main task would be to serve the people. He aspired to make India universal through this manifesto.

Beginning the Fight for Freedom

Knowing he could not openly join the freedom movement while in government service, Aurobindo began to express his thoughts in political writings, starting with a series of seven articles in the Induprakash in 1893. The series heavily criticized the then Indian National Congress under the title “New Lamps for Old.” During his stay in Baroda, one can see how selflessness was imbued in Sri Aurobindo. He wrote not for personal recognition but to sow the seeds of uncompromising freedom in the minds of Indians.

Bipin Chandra Pal—nationalist, writer, orator, reformer and Indian-independence freedom fighter and Sri Aurobindo’s colleague during his revolutionary life—wrote of Aurobindo’s writings, especially his articles in Bande Mataram, a newspaper owned by Pal: “The hand of the master was in it from the very beginning. Its bold attitude, its vigorous thinking, its clear ideas, its chaste and powerful diction, its scorching sarcasm and refined witticism were unsurpassed by any journal in the country, either Indian or Anglo-Indian.” Sister Nivedita termed him “the real protagonist of Indian nationalism,” strongly opining that it was Aurobindo who gave Indian nationalism a “creative expression.” In turn, research shows, he respected the Scottish disciple of Vivekananda, regarding her book, Kali the Mother, as inspiring to Indians fighting for freedom.

Marriage

While in Baroda, another chapter of Aurobindo’s life would unfold. In April 1901, at age 28 he decided to marry Mrinalini Devi, age 14, daughter of Bhupal Chandra Bose, a distinguished attorney, after meeting her through a matrimonial advertisement he put out seeking to marry a Hindu girl according to Hindu rites. Dr. Kavita Sharma, former President of the South Asian University, writes that after four years of marriage Aurobindo decided to part ways with Mrinalini, saying it was due to a generational gap. Others suspect he was being drawn more into politics, revolutionary activities and the nascent stages of his encounters with yoga.

The book, Sri Aurobindo’s Letters Written to His Wife Mrinalini Devi, reveals she never came in the way of his work and spiritual practice. After Aurobindo left Bengal, he never met Mrinalini again. She contemplated receiving sannyasa diksha (monastic initiation) from the Ramakrishna Mission order. Aurobindo disallowed this but promised her spiritual support. She longed to join him in Pondicherry (Puducherry), but fate would have it otherwise. She died of influenza at the age of 32.

His famous letter to Mrinalini on August 30, 1905, in which he recounted his “three madnesses,” symbolizes his vision of God and country. He described the first madness as regarding whatever accomplishments and wealth he had gained as belonging to God. The second madness, he wrote, is his deep desire for a direct vision of God; and the third madness is that he looked at his country as a Mother while others looked at it as an “inert piece of matter.”

Deeper into the Freedom Movement

Aurobindo’s revolutionary vision took wings after an outbreak of protests following the partition of Bengal by the British in 1905. He gave up the Baroda Service in 1906 and moved to Kolkata as principal of the newly founded Bengal National College. There he urged students to explore different ways to give back to India, their motherland. His nationalism did not merely mean that one’s country came first; it meant a total rebirth of India through the prism of a civilizational ethos that would be a beacon, a guiding light, for the world.

In 1906, Aurobindo was editing the newspaper Bande Mataram. He also wrote articles in Jugantar Patrika, a Bengali weekly, focusing on the partition of Bengal. Bande Mataram was not outwardly advocating an armed end to British rule, but in several articles Jugantar Patrika clearly espoused an open, armed revolt against the British. Aurobindo was arrested in 1907 on sedition charges for some of his articles that appeared in Bande Mataram. However, the court found no evidence of sedition in the writings and he was released. This sedition case began the real unfolding of his notoriety as a revolutionary.

He drew inspiration from Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who epitomized swaraj, self-rule, and gave the famed clarion call, “Swarajya is my birthright and I shall have it.” He also championed the swadeshi movement, which called for Indians to boycott British goods and buy Indian products. Aurobindo rightfully called Tilak a “great mind, great will, and a great pre-eminent leader.”

Tilak also inspired Aurobindo’s worldview on castes. In one of his articles for Bande Mataram, entitled “Un-Hindu Spirit of Caste Rigidity,” Aurobindo wrote, “The Bengalee reports Srijut Bal Gangadhar Tilak to have made a definite pronouncement on the caste system. ‘The prevailing idea of social inequality is working immense evil,’ says the Nationalist leader of the Deccan. This pronouncement is only natural from an earnest Hindu and a sincere Nationalist like Srijut Tilak.”

Aurobindo, in his work as a revolutionary, believed in communicating his ideas for complete independence, self-reliance, self-rule and for building individuals who would carry forward this idea to the masses. He lived at a time when common minds thought independence was a far-fetched ideal. But he wanted an awakening, one spark to ignite the country. Even through a cursory look at his life, one would conclude he succeeded in communicating his political ideas in acts that ultimately shook the foundations of the British empire.

Praise from His Peers

Be it Rash Behari Bose, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Rabindranath Tagore, Bharathiyar or Sister Nivedita, they all looked to Sri Aurobindo for his inspirational vision of seeing India as a global contributor to thought and humanity purely through the strength of knowledge.

In The Transformation, a video documentary on Sri Aurobindo, Rash Behari Bose, one of the founders of the Indian National Army, said it was Sri Aurobindo who embodied “positive Indian nationalism.” Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose described him as his spiritual guru, as one of the most “popular leaders of Bengal” and a “fearless advocate of Independence.” Netaji Bose went on to add that Aurobindo was his “spiritual guru” to whom he had dedicated his mind and soul. Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore defined him as “the voice incarnate of India’s soul.” True to this, his life inspired not only the minds in the east of India but across the length and breadth of the nation.

Man-Making Through Institutions

Aurobindo foresaw that India needed men and women of steel who could help realize his vision and establish her rightful place in the comity of nations. His vision was to set up institutions with this sole purpose, and the Bengal National College was no exception. Aurobindo’s vision was that any education must be in tune with a student’s svabhava, true nature.

His stirring speech “Advice to Students,” given at the college on August 23, 1907, prior to his arrest by the British in the Bande Mataram sedition case, stands as proof of his vision for education. “What we want here is not merely to give you a little information, not merely to open to you careers for earning a livelihood, but to build up sons for the motherland to work and to suffer for her,” he proclaimed. “That is why we started this college and that is the work to which I want you to devote yourselves in future. What has been insufficiently and imperfectly begun by us, it is for you to complete and lead to perfection. I wish to see some of you becoming great—great not for your own sakes, not that you may satisfy your own vanity, but great for her, to make India great, to enable her to stand up with head erect among the nations of the earth, as she did in days of yore when the world looked up to her for light.

“Even those who will remain poor and obscure, I want to see their very poverty and obscurity devoted to the motherland. If you will study, study for her sake, train yourselves body and mind and soul for her service. You will earn your living that you may live for her sake. You will go abroad to foreign lands to bring back knowledge with which you may render service to her. Work that she may prosper. Suffer that she may rejoice. All is contained in that one single advice.”

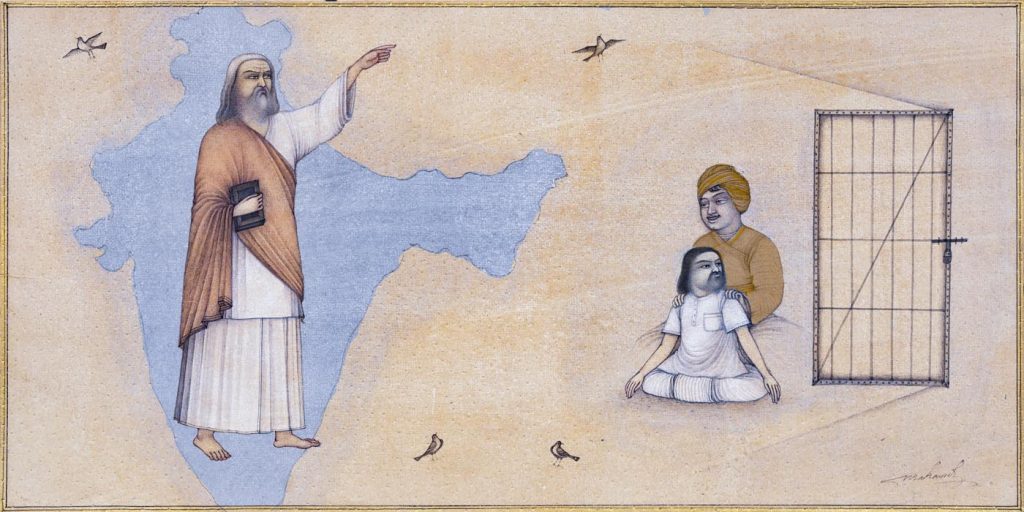

Prison’s Profound Impact

The turning point in Aurobindo’s life was the Alipore Bomb Case involving the Anushilan Samiti group in Bengal. The group, which was at the forefront of initiating revolutionary violence against the British, spent its time teaching young recruits how to make bombs. Among targets of the group was the British magistrate Douglas Kingsford. Two young revolutionaries, Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose, were sent to assassinate him. In April 1908, the duo hurled bombs at Kingsford’s carriage, but it was not he in the carriage, but another British barrister’s wife and daughter, who were killed.

While fleeing, Prafulla Chaki fatally shot himself to avoid capture. Khudiram Bose was arrested and hanged at the age of 18. Further investigation led the police to arrest Aurobindo. After exactly a year of trial, during which he was imprisoned, the court acquitted Aurobindo and others. Some faced life imprisonment, but were later released, and some received life sentences.

The lengthy trial and his year in prison had a profound impact on Aurobindo. Cornelissen documented: “His incarceration had one major effect, which the British police could not have foreseen, or, for that matter, understood. Aurobindo took his arrest and yearlong incarceration as a God-imposed opportunity to concentrate fully on his inner, spiritual development, or sadhana. While in jail, he showed remarkably little concern about the court-case, but made an in depth study of the Bhagavad Gita and realized the presence of the personal Divine in everything and everybody around him.

“In his own words, ‘It was while I was walking that His strength again entered into me. I looked at the jail that secluded me from men and it was no longer by its high walls that I was imprisoned; no, it was Vasudeva who surrounded me. I walked under the branches of the tree in front of my cell, but it was not the tree, I knew it was Vasudeva, it was Srikrishna whom I saw standing there and holding over me His shade. I looked at the bars of my cell, the very grating that did duty for a door and again I saw Vasudeva. It was Narayana who was guarding and standing sentry over me.’ ”

He spent considerable time on his spiritual practice, striving to transform himself and understand his life’s true purpose. He later compared his stay in prison to living in an ashram or hermitage where human relations ceased. He further alluded to this year as an experience of finding God and the divine presence. Aurobindo said he could “feel” Swami Vivekananda—from whom he derived great inspiration—speaking to him for a fortnight. This voice spoke of an important field of spiritual experience, higher consciousness or “truth consciousness.” In his farewell speech at Uttarpara after his release from jail, he resolutely declared his commitment to the Bhagavad Gita, urging everyone to realize Lord Krishna, as he felt it was He who was guarding and rejuvenating him.

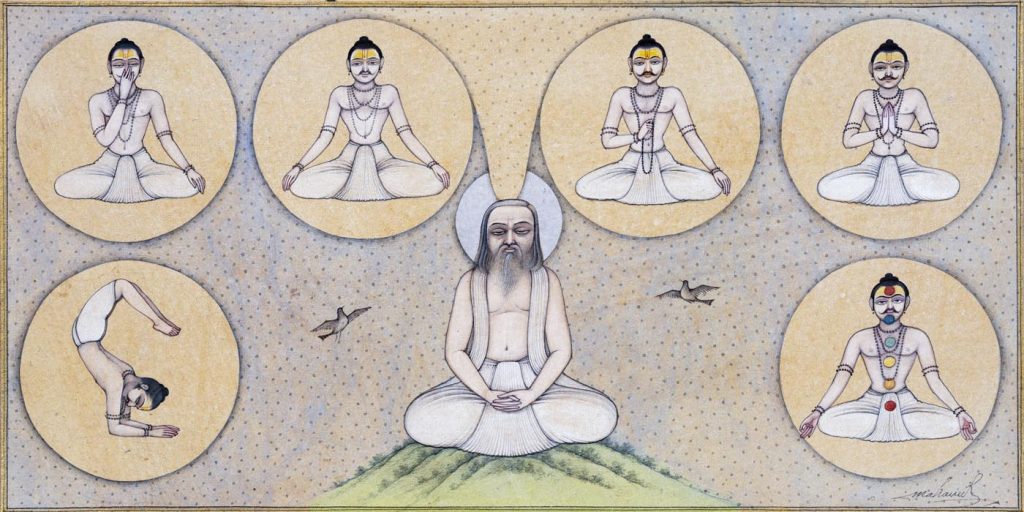

Aurobindo was largely independent, learning the basics and essence of yoga without a guru. He declared that his sadhana was not founded on books but purely on his personal experiences. By some accounts he started practicing yoga after receiving the rules of yoga from a friend and disciple of Brahmananda of Ganga Mutt. He later met with a naga sannyasi, whose powers amazed him. Subsequently, a Maharashtrian yogi, Vishnu Baskar Lele, tutored him in the fundamentals of yoga. Aurobindo wrote in a letter that he was initiated in 1904, and in 1908 was further taught by Lele. According to The Lives of Sri Aurobindo by Peter Heehs, after meeting with Lele, Aurobindo went into seclusion for three days. Following the yogi’s instructions, he had his first major spiritual experience—said to be a nirvana state of perfect quiescence, free all mental activity.

Cornelissen wrote: “Within three days he managed under Lele’s guidance to completely, and permanently, silence his mind. Soon after, he had the realization of the silent, impersonal Brahman in which the whole world assumed the appearance of ‘empty forms, materialised shadows without true substance’. . . . The presence of the silent Brahman never left Aurobindo, though it subsequently merged with other realizations of the Divine. Interestingly, all this happened during one of the busiest periods of his life while he was at the peak of his political influence, and he managed, in his own words, to organise political work, deliver speeches, edit his newspaper and write articles, all from an entirely silent mind.”

A Higher Calling

After his release from prison in 1909, Aurobindo continued writing, launching two weeklies, Karmayogin in English and Dharma in Bengali. They explored religion, literature, science and philosophy, among other subjects. He edited and wrote translations of Upanishads in Karmayogin. The British again tried to prosecute him for a purportedly seditious article in Karmayogin, but this time he fled to the French enclave of Pondicherry via Chandernagore. Sister Nivedita edited Karmayogin until it ceased publication in 1910. The Dharma weekly folded the same year.

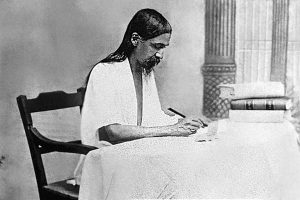

Once settled in Pondicherry, Aurobindo became fully dedicated to his spiritual and philosophical pursuits. In 1914, after four years of consistent yoga, he began expressing his wisdom on paper, launching the 64-page monthly called Arya, which for the next six years was the vehicle for his major works, in serial form, which were later published in book form—The Upanishads (1922), Essays on the Gita (1928), The Life Divine (1940), The Synthesis of Yoga (1948), The Human Cycle (1949), The Ideal of Human Unity (1949), The Foundations of Indian Culture (1953) and On the Veda (1956).

About his writing the Times Literary Supplement of London wrote: “He is a new type of thinker, one who combines in his vision the alacrity of the West with the illumination of the East. He is a yogi who writes as though he were standing among the stars, with the constellations for his companions.” Sri Aurobindo wrote in various languages, including Bengali, Sanskrit, and French, but is best known for his works in English, which he used to express his philosophical and spiritual ideas.

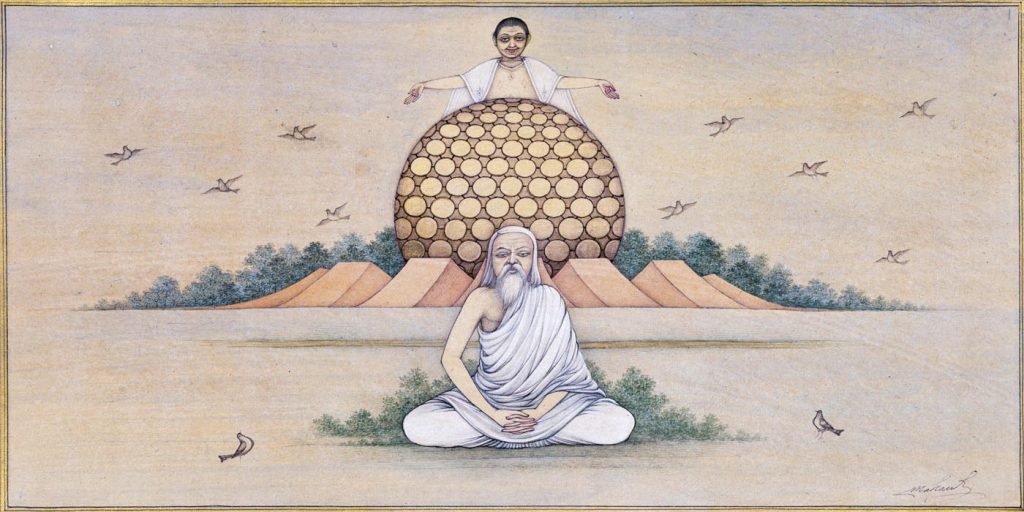

The Mother

In 1914, Mirra Alfassa, a Jewish mystic born in Paris in 1878 to Turkish and Egyptian parents, first met the rishi, who was six years her senior. She was profoundly moved by that first meeting, writing that on that day she had met Krishna: “It matters little that there are thousands of beings plunged in the densest ignorance, He whom we saw yesterday is on Earth; his presence is enough to prove that a day will come when darkness shall be transformed into light, and Thy reign shall be indeed established upon earth.” In 1920 she began to permanently reside in Pondicherry as Aurobindo’s spiritual collaborator. In 1926, they founded the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. He withdrew from active participation later that year, leaving day-to-day management and further development to Alfassa. In 1943, she started an ashram school. In 1968, at the age of ninety, she formally established Auroville, an experimental township dedicated to human unity and evolution located six miles from Aurobindo Ashram. She died on November 17, 1973, at age 95, in Pondicherry.

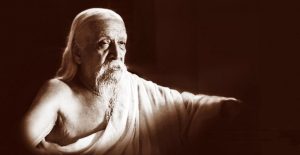

“We know relatively little about what Sri Aurobindo did during the 24 years after his retirement to his rooms,” Cornelissen chronicled. “He spoke hardly to anybody, except for a short period just before the Second World War when he needed physical assistance after breaking his leg, and he saw his disciples only three to four times a year in a silent ‘darshan.’ What we know of his inner life during this period is largely from his letters, from his poetry, and from the changes he introduced in some of his earlier writings. During the 1930s, Sri Aurobindo answered a staggering number of letters to his disciples, of which over 5,000 have been published. Most of them deal with sadhana, quite a few with literature, and a smaller number with other issues. Roughly during the same time he also took up the revision of a few of his major works like his Essays on the Gita, the first two parts of The Synthesis of Yoga, and The Life Divine.” From the late thirties onward, his primary pursuit was the 24,000-line epic poem Savitri.

Essential Teachings

Aurobindo’s essential teachings state that behind the appearance of the universe there is consciousness. Although this is united by that one Self, it is separate, but it is possible to remove that veil and become aware of the true self by virtue of psychological discipline. Evolution certainly enables this, but the process does not stop there. Life is the first step, with the next being the development of the supermind and spirit. The aim is simple, that one can discover Self and not just stay there, but evolve to a higher consciousness.

Aurobindo and the Mother worked on the descension of the supramental force on the mind. This was the ultimate transformation, according to the rishi. Aurobindo’s core philosophy is best described by A.B. Purani, one of his biographers: “Sri Aurobindo advocates the control of Matter by the Spirit, but to be able to do that, man must rise above his present state of consciousness. He must rise from his mental consciousness to the truth-consciousness, to the super-mind.”

Aurobindo was prolific, completing a huge body of work. According to Reading Sri Aurobindo, the master’s printed work exceeds 21,000 pages, almost six million words. His writings are not easily approached. I have read and re-read some of his works, as have many of today’s young readers. One has to delve deep and ponder even deeper to understand him. Dr. Frawley quipped, “For Aurobindo a sentence can be a paragraph and a paragraph can run into pages.” He also uniquely allowed contrary opinion in his works, further making it difficult to understand his philosophical scope because it is many-sided, a rare feat very few writers in Indian history managed with such aplomb. Having lived in and learned from the West, Aurobindo felt Western thought was not adequate for genuine seekers. He forecast, according to Dr. Frawley, that Western thought would degenerate into many ideologies, and its culture was in decline. In comparison, Aurobindo strongly felt independent Indian thought was strong and steady.

Heralding the Vedas

Central among Aurobindo’s teachings was his call for people to return to the philosophy and understanding of the Vedas. In his words, “The recovery of the perfect truth of the Veda is therefore not merely a desideratum for our modern intellectual curiosity, but a practical necessity for the future of the human race.” He encouraged seekers to set their sights on the truth of the Veda through revelation and experience. Aurobindo believed revelation, inspiration, intuition and intuitive discrimination are the preeminent processes of ancient inquiry.

The Sri Aurobindo Archives and Research, issues December 1985 and April 1997, record he was convinced that Hinduism sprouted into existence from the seed called the Veda. “At the root of all that we Hindus have done, thought and said through these many thousands of years, behind all we are and seek to be, there lies concealed the fount of our philosophies, the bedrock of our religions, the kernel of our thought, the explanation of our ethics and society, the summary of our civilization, the rivet of our nationality, a small body of speech—Veda. The Veda was the beginning of our spiritual knowledge; the Veda will remain its end.”

His core thoughts on interpreting the Vedas are found in the Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol. 15: “The hypothesis on which I shall conduct my own inquiry is that the Veda has a double aspect, and that the two, though closely related, must be kept apart. The Rishis arranged the substance of their thought in a system of parallelism by which the same deities were at once internal and external powers of universal nature, and they managed its expression through a system of double values by which the same language served for their worship in both aspects. But the psychological sense predominates and is more pervading, close-knit and coherent than the physical. The Veda is primarily intended to serve toward the spiritual enlightenment and self-culture. It is, therefore, this sense which has to be first restored.”

In Volume 16 he continues, “The Vedic rishis were mystics who reserved their inner knowledge for the initiates; they shielded it from the vulgar by the use of an alphabet of symbols which could not readily be understood without the initiation, but they were perfectly clear and systematic when the signs were once known.” In the same volume, he laid down processes for interpreting the Vedas. First, it must be a “straightforward rendering word by word of the text.” Second, it has to be “seen for what its actual purport and significance is,” and third, “if a symbolic interpretation is put on any part of the text, it must arise directly and clearly from suggestions and language of the Veda itself and must be brought in from outside.”

Let’s look at an example, widely cited without attribution, to illustrate this idea. Indra is the God of mind lording over the Indriyas, that is, the senses. Vayu represents air, but in its esoteric sense means prana, or the life force. So when the Rig Veda says “Call Indra and Vayu to drink Soma Rasa,” the inner meaning is to use mind through the senses and life force to receive divine bliss. Agni, the God of the sacrificial fire in the outer sense, is the flame of the spiritual will to overcome the obstacles to unite with the Divine. Thus the sacrifice of the Vedas could mean sacrificing one’s ego to the internal Agni, the spiritual fire.

Impact and Legacy

The message of Sri Aurobindo is not confined within the borders of India, but lives in followers’ hearts and small institutions on several continents, even though he never traveled to propagate his thoughts and ideals. A.B. Purani emphasized this in his Sri Aurobindo Life Divine Lectures in the United States. G.H. Langley, in his book Sri Aurobindo, Indian Poet, Philosopher and Mystic, wrote, “Sri Aurobindo is both a poet and a speculative thinker. The same is true of Rabindranath Tagore, but the thought of Sri Aurobindo appears to me more comprehensive and systematic than that of Tagore.” Dr. Frederic Spiegelberg of Stanford University wrote that he “had never known a philosopher so all-embracing in his metaphysical structure as Sri Aurobindo. None before him had the same vision. I can foresee the day when the teachings—which are already making headway—of the greatest spiritual voice of India, Sri Aurobindo, will be known all over America and be a vast power of illumination.”

Auroville was envisioned as a place for the future, especially those who seek a vision of peace, unity and knowledge. Alfassa, the Mother, was the prime mover behind the creation of Auroville, which she founded eighteen years after Aurobindo left his body. Since its inception, Auroville has received widespread coverage in Western media, positive and negative, some calling it the “capital of a spiritual empire.” It has attracted seekers from Western countries, especially France and the US, with many making it their permanent home. UNESCO has termed Auroville “Aurobindo’s city of global unity.” People from India and other countries throng there for spiritual benefit. My family and I are regular visitors to the ashram and the Matrimandir, finding Auroville an important place for pilgrims to soothe our minds. There are centers all over the world promoting Aurobindo’s thought.

In 1972, Aurobindo’s birth centenary year was celebrated. In 2022, the 150th year of his birth, the government of India released a commemorative coin and postage stamp. According to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Aurobindo’s life and message continue to inspire generations and he “left his impressions wherever he went.”

Irina Bokova, former UNESCO director general, summed up Aurobindo in today’s context, “To him we also owe the magisterial commentary of the Bhagavad Gita, the gift of sharing understanding of Hinduism’s deepest sources across all borders, the gift of drawing bridges of understanding between Western and Eastern cultures, between all societies. The life of Sri Aurobindo was inspired by a deep devotion to human dignity and freedom, guided by his vision of life as an opening of the mind. The stars might find it is no coincidence he was born on the day that India achieved independence. Aurobindo appealed for unity, peace, and concord, qualifying his great nation as a ‘helper and leader of the whole human race.’ Sri Aurobindo embodied the conviction that the ethical and spiritual dimension—the quest for self-knowledge—offered the most fertile ground for creating more peaceful, just and harmonious societies.”

It is important to understand Aurobindo’s life in a contemporary framework. He was an original thinker and a man of ideas. It will be fitting if we pick up any one of his readings, letters or speeches to explore the depths of his persona. It is also important not to de-Indianize him, nor claim that his vision was and is universal and not Indian. This is the very least one can do towards the maharishi who said, “All life is yoga.” His 150th birthday could be the perfect opportunity to strive towards a holistic, inclusive model India that can present to the world as he envisioned.

Critics may criticize Aurobindo for being an escapist because he fled the Indian freedom struggle at its peak in pursuit of higher living, or that his writings may overly adopt Victorian English, or that he professed a philosophy that is opaque and difficult to comprehend. But there is no escaping the fact that he stands tall as an author of India’s spiritual story. It is up to us, “we the people,” to read through and understand the real Aurobindo.

Early in life Aurobindo Ghose took a violent, coercive path to overthrow the British through his revolutionary writings and activities. But that is just one side of his biography. The other side, more enduring, is that he understood early on how to nurture in others a persuasive attraction to spirituality and was himself its embodiment. Today, Indian spiritual thought inspires seekers around the globe and serves as a guiding force to fight for peace. His evolution from political radical to ascetic yogi can be best understood, in modern terms of international relations, as a transition from hard power to soft power.

Final Message

In a radio broadcast on India’s independence day, August 15, 1947, his 75th birthday, Aurobindo put forth his five lifetime dreams for the benefit of India, the world and humanity at large. He felt that even though India was, after too long a time, now politically free, it needed to be united. Hence, his first dream was “a revolutionary movement that could create a free and united India.” The second dream was for the “resurgence and liberation of the peoples of Asia and Asia’s return to her great role in the progress of human civilization.” His third dream was a “world union forming the outer basis of fairer, brighter and nobler life of mankind.” The fourth was that the “spiritual gift of India to the world has begun,” and the fifth was raising “human evolution to higher consciousness to bring about solutions to problems.” Sri Aurobindo made his transition on December 5, 1950. His body was entombed without cremation in a chamber called The Samadhi located within the Aurobindo Ashram complex. It is a place of pilgrimage and worship for many of Sri Aurobindo’s followers.

About the Author

Sudarshan Ramabadran, author and researcher, is currently studying at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in the master of public diplomacy program. He was a Professional Fellow for Governance and Society, South and Central Asia Program in Washington D.C., an exchange program run by the U.S. Department of State. In April 2021, he co-authored the book, Makers of Modern Dalit History, aimed at highlighting pioneering Indians on diversity, equity and inclusion.

From His Epic Poem, Savitri

Thought falls from us, we cease from joy and grief;

The ego is dead; we are freed from being and care,

We have done with birth and death and work and fate.

O soul, it is too early to rejoice!

Thou hast reached the boundless silence of the Self,

Thou hast leaped into a glad divine abyss;

But where hast thou thrown Self’s mission and Self’s power?

On what dead bank on the Eternal’s road?

One was within thee who was self and world,

What hast thou done for his purpose in the stars?

Escape brings not the victory and the crown!

Something thou cam’st to do from the Unknown,

But nothing is finished and the world goes on

Because only half God’s cosmic work is done.

Only the everlasting No has neared

And stared into thy eyes and killed thy heart:

But where is the Lover’s everlasting Yes,

And immortality in the secret heart,

The voice that chants to the creator Fire,

The symbolled OM, the great assenting Word,

The bridge between the rapture and the calm,

The passion and the beauty of the Bride,

The chamber where the glorious enemies kiss,

The smile that saves, the golden peak of things?

This too is Truth at the mystic fount of Life.

Evolution’s Potent Momentum

Excerpted from

www.sriaurobindoashram.org/faq/yoga.php

Sri Aurobindo’s teaching states that there is a one Being and Consciousness involved here in Matter which is impelled to enlarge and develop towards a greater and greater perfection. Life and Mind are only the first two steps of this evolution. The next step of the evolution must be towards development of a greater spiritual and supramental Consciousness which will release the involved Divinity in things, after which it will become possible for life to manifest perfection.

In Sri Aurobindo’s view, Man, at present, lives mostly in his surface mind, life and body. There is an inner being within which pushes him to a constant pursuit of a greater beauty, harmony, power and knowledge. He has to awaken to the greater possibilities of this inner being and purify and orient, by its drive towards the Truth, the rest of the nature. There can follow afterwards an opening upward to the several ranges of consciousness between the ordinary human mind and the Supramental Truth-Consciousness, and their power brought down into the mind, life and body. This will enable the full power of the Truth-Consciousness to work in the nature….The process of this discipline is therefore long and difficult, but sustained effort in this direction brings the seeker ever closer to the goal of this Yoga.

Encountering Mother Kali

In 1905, during his travels around Baroda, Aurobindo visited a Goddess Kali temple in Chandod on the banks of the Narmada River. There, according to his biography, he experienced a palpable living presence of Kali manifesting before him, a life-altering experience he captured in the following poem.

The Stone Goddess

From sculptured limbs the Godhead looked at me,

A living Presence deathless and divine,

A Form that harbored all infinity.

The great World-Mother and Her mighty will

Inhabited the earth’s abysmal sleep,

Voiceless, omnipotent, inscrutable,

Mute in the desert and the sky and deep.

Now veiled with mind She dwells and speaks no word,

Voiceless, inscrutable, omniscient,

Hiding until our soul has seen, has heard

The secret of Her strange embodiment,

One in the worshiper and the immobile shape,

A beauty and mystery flesh nor stone can drape.

The Supreme Truth-Consciousness

From Sri Aurobindo’s The Life Divine

One seated in the sleep of Superconscience, a massed Intelligence, blissful and the enjoyer of Bliss. . . . This is the omnipotent, this is the omniscient, this is the inner controller, this is the source of all.

Mandukya Upanishad, verse 1

We have to regard, therefore, this all-containing, all-originating, all-consummating Supermind as the nature of the Divine Being, not indeed in its absolute self-existence, but in its action as the Lord and Creator of its own worlds. This is the truth of that which we call God. Obviously this is not the too personal and limited Deity, the magnified and supernatural Man of the ordinary occidental conception; for that conception erects a too human Eidolon of a certain relation between the creative Supermind and the ego. We must not indeed exclude the personal aspect of the Deity, for the impersonal is only one face of existence; the Divine is All-existence, but it is also the one Existent—it is the sole Conscious-Being, but still a Being. Nevertheless, with this aspect we are not concerned at present; it is the impersonal psychological truth of the divine Consciousness that we are seeking to fathom: it is this that we have to fix in a large and clarified conception. The Truth-Consciousness is everywhere present in the universe as an ordering self-knowledge by which the One manifests the harmonies of its infinite potential multiplicity. Without this ordering self-knowledge, the manifestation would be merely a shifting chaos, precisely because the potentiality is infinite—which by itself might lead only to a play of uncontrolled, unbounded Chance.”

On His Synthesis of Yoga

From Sri Aurobindo’s The Life Divine

In practice, three conceptions are necessary before there can be any possibility of Yoga; there must be, as it were, three consenting parties to the effort—God, Nature and the human soul or, in more abstract language, the Transcendental, the Universal and the Individual. If the individual and Nature are left to themselves, the one is bound to the other and unable to exceed appreciably her lingering march. Something transcendent is needed, free from her and greater, which will act upon us and her, attracting us upward to Itself and securing from her by good grace or by force her consent to the individual ascension.

It is this truth which makes necessary to every philosophy of Yoga the conception of the Ishwara, Lord, supreme Soul or supreme Self, towards whom the effort is directed and who gives the illuminating touch and the strength to attain. Equally true is the complementary idea so often enforced by the Yoga of devotion that as the Transcendent is necessary to the individual and sought after by him, so also the individual is necessary in a sense to the Transcendent and sought after by It. If the Bhakta seeks and yearns after Bhagavan, Bhagavan also seeks and yearns after the Bhakta. There can be no Yoga of knowledge without a human seeker of the knowledge, the supreme subject of knowledge and the divine use by the individual of the universal faculties of knowledge; no Yoga of devotion without the human God-lover, the supreme object of love and delight and the divine use by the individual of the universal faculties of spiritual, emotional and aesthetic enjoyment; no Yoga of works without the human worker, the supreme Will, Master of all works and sacrifices, and the divine use by the individual of the universal faculties of power and action. However Monistic may be our intellectual conception of the highest truth of things, in practice we are compelled to accept this omnipresent Trinity.

The Rishi’s Lifestyle & Habits

Excerpts from the website collectedworksofsriaurobindo.com

“The routine of his daily life was as follows: After morning tea Sri Aurobindo used to write poetry. He would continue up to ten o’clock. Bath was between ten and eleven o’clock and lunch was at eleven o’clock; a cigar would be by his side ,even while he ate. Sri Aurobindo used to read journals while taking his meals.”

“He took less of rice and more of bread. Once a day there was meat or fish. There were intervals when Sri Aurobindo took to complete vegetarian diet. He was indifferent to taste. He found Marathi food too hot (with its chilies) and Gujarati food too rich in ghee. Later, he once had a dinner at B.G. Tilak’s, which consisted of rice, puri, legume (dal) and vegetables. He liked it for its ‘Spartan simplicity.’ ”

“Desireless, a man of few words, balanced in his diet, self-controlled, always given to study, reading far into the night, and hence a late riser. . . . Aurobindo talked very little, perhaps because he believed it better to speak as little as possible about oneself. . . . It was as if acquiring knowledge was his sole mission in life.” (The Bengali tutor, Dinendra Kumar Roy)

R.N. Patkar, a student of Aurobindo: “At home he was clad in plain white sadara and dhoti and outside invariably in white drill suits. He never slept on a soft cotton bed, as most of us do, but on a bed made of coir (coconut fibers) on which was spread a Malabar grass mat which served as a bedsheet. Once I asked him why he used such a coarse, hard bed and he said with his characteristic laugh, ‘My boy, don’t you know that I am a brahmachari? Our shastras enjoin that a brahmachari should not use a soft bed, which may induce him to sleep.’ ”

“Books, books were his major preoccupation; the Bombay firms of booksellers, Thacker Spink and Radhabai Atmaram, supplied him regularly with the latest catalogs, and he then placed orders for selected books which duly arrived in bulky parcels by passenger train. His personal library thus came to include some of the latest books in English, French, German, Latin, Greek and, of course, all the major English poets, from Chaucer to Swinburne. . . . But because he liked this reading did not mean that he did not join us in our talks and chats and our merrymaking. His talk used to be full of wit and humor.”

“Beyond a nodding acquaintance with the broad ideas of certain European philosophers, he had no interest in the highways and byways of Western philosophical thought. Of the Indian philosophers also he had read only some of their main conclusions. Actually, his first real acquaintance with Indian spirituality was through the reported sayings of Ramakrishna Paramahansa and the speeches and writings of Swami Vivekananda. Sri Aurobindo had certainly an immense admiration for Vivekananda and a still deeper feeling for Ramakrishna.”

“Sri Aurobindo was loved and highly revered by his students at Baroda College, not only for his profound knowledge of English literature and his brilliant and often original interpretations of English poetry, but for his saintly character and gentle and gracious manners. There was a magnetism in his personality, and an impalpable aura of a lofty ideal and a mighty purpose about him, which left a deep impression upon all who came in contact with him, particularly upon young hearts and unsophisticated minds. Calm and reserved, benign and benevolent, he easily became the center of respectful attention wherever he happened to be. To be close to him was to be quieted and quickened; to listen to him was to be fired and inspired. Indeed, his presence radiated something which was at once enlivening and exalting. His power sprang from his unshakable peace, and the secret of his hold on men lay in his utter self-effacement. His greatness was like the gentle breath of spring, invisible but irresistible, it touched all that was bare and bleak around him to a splendor of renewed life and creative energy.”