Sign of the times: Our writer didn’t need to leave India to interview ardent meditators from Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Christianity and more

By Anne Petry, France/India

Meditation… is there any other action, or should we say “non-action,” that is so ancient and so modern at the same time? While in some countries, such as India, the practice of meditation has remained in people’s habits, the practice there has deteriorated over time. But fortunately this is changing! Whereas meditation was initially linked to a religious context, and still is for most people, it has also become for many a more or less secular practice used to calm the stress and anxiety generated by our modern lifestyle. This has led to a resurgence of interest among younger generations in Asia and all over the world.

Sneha: Meet Sneha, a 31-year-old modern Indian woman in Chennai, who told me: “While it’s normal and natural for us Indians to sit cross-legged on the floor, it’s not innate for us to sit still for any length of time without apprehending the thoughts that are constantly popping into our heads. As with every other person in the world, peace of mind is a matter of practice. And in this respect, I’m what you might call a ‘beginner.’ I’ve learned a few meditation techniques here and there, from talking to family and friends or at school; but until recently, I wouldn’t say that meditation was a regular part of my daily life. However, I’ve just finished my second meditation retreat, and I can say that it has helped the energetic young woman in me to become more focused and calm. I know I need to deepen my practice to feel the full benefits, but I don’t want to force anything, I’m going at my own pace, slowly discovering the different techniques that exist, step by step.”

Rex Benedict: For others, meditation came earlier and immediately had a profound impact. Rex Benedict, 28, an Indian man from Coimbatore, shares, “My journey to meditation was the result of a spiritual awakening that occurred during a challenging period when I was 21, when past-life karma resurfaced, plunging me into what I’d describe as a ‘dark mode.’ It was a critical phase in my life, but I have been fortunate to receive guidance from gurus who helped me find my path. Today, I formally meditate for about 40 minutes every morning when I wake up and I feel immense peace, stability and clarity. It is also a powerful tool for finding answers when I am seeking advice. My meditation techniques vary. Sometimes I practice mantra japa dedicated to Lord Siva; other times, I concentrate on my breath, or let the energy flow through my spine. I also practice focusing on the center of my forehead, playing with my ego and dissolving it, and finally focusing on the chakras. I’m very fortunate to have several people in my circle of friends, both Indian and Western, who have their own spiritual path. Each of our encounters reaffirms a notion that is very dear to me: the universality of meditation.”

This universality that Rex mentions is important. Meditation is too often thought of as an “Indo-Asian” practice reserved for Hindus and Buddhists. But Avi Farzan, who was born in Israel and has lived in the United States, bears witness to the fact that meditation is also used in Judaism: “I met my guru, Swami Muktananda, in 1979; he is the one who brought me to meditation. Today, in addition to self-inquiry, I like to meditate alone in my room, several times a day; it brings me profound peace of mind, and I definitely feel more focused. Although I now live in India, every time I return to my home country, Israel, I see a renewed interest in meditation, particularly among the youngsters.

“What many people don’t know is that meditation has always been a major practice in Judaism, with techniques as diverse as visualization, the use of psalm chants, concentration on philosophical or mystical ideas, introspection and contemplation of divine names. These meditations can be part of prayer practices or separate from them. Over time, meditation practices have been developed in many movements, such as the Kabbalah, a set of esoteric teachings designed to explain the relationship between the unchanging, eternal God—The Infinite—and the mortal, finite universe which is God’s creation. Kabbalah forms the foundations of the mystical religious interpretations within Judaism. One of the many types of Kabbalah meditation, for example, involves returning to the here and now, connecting our mind with that of others and creating new channels of connection, love and openness in order to strengthen humanity as a whole. Through visualization, we also connect our soul to the Source, open ourselves to the divine current and feel the holiness and transcendence of the different dimensions of the Divine.”

Shankar Nair: In Sufism, according to Professor Shankar Nair of the University of Virginia, there is a particular meditation practice called Mouraqaba (“observation”), also known as the vigilance exercise. The meditator kneels down—eyes closed, thumb touching index finger, breathing under control—and focuses all attention on a single point. This point is usually the visualization of the Sheikh, one’s Sufi master, seen as a bridge between the world of illusion and that of reality. The aim is to gradually reach what is known as the state of “obliteration” (absence from the world of the senses), or the highest state, which is “extinction.” In this state, attachment to the material world, to the grip of the senses, will diminish, and the absolute emptiness of God should descend upon the meditator.

As we can see, meditation is within the reach of many adults around the world, since it is practiced in some form in most major religions, as well as in secular settings. But it is also becoming a practice accessible to younger people, as it is increasingly integrated into school systems, particularly in India. Manikandan Ramanandan, 36, a meditation and yoga teacher, has been working for eight years at Shanthimalai School in Tamil Nadu, South India. This school, which has around 800 students, took a pioneering step a few years ago when they decided to integrate meditation classes into the curriculum for children age six and up. Mani explains: “At this early age, children are very curious and quick learners. So we teach them meditation through mantras, control of prana (energy) as well as relaxation and yoga postures. While I see them sometimes reluctant to go to math or Tamil classes, I always find that they’re happy to come to the meditation class, and I’ve noticed that when they leave my class, they’re more disciplined and definitely more energetic than they were when they arrived.”

Mahi: Certain children seem to be born with a native aptitude for spirituality in general and meditation in particular. I met seven-year-old Mahi at Ramana Ashram, in South India. Of Indian origin, she was born in Australia. Because Sri Ramana Maharshi’s teachings have always resonated strongly with Mahi’s father, he felt the need to bring Mahi and her sister to this place. Mahi happily answered my questions: “I meditate every day, more or less 30 minutes a day. I usually meditate in the morning before going to school, but when I’m late, I take advantage of the ride to school in my mum’s car to do my meditation. It doesn’t really matter where I am, I can meditate anywhere, but my favorite place is in my room, with my big sister next to me. Sometimes I use mantras my father taught me, but most of the time I stay with the question, ‘Who am I?’ This question makes all my thoughts disappear. When the thoughts come back, I ask myself again, ‘Who am I?’ I know I’m not the body, I’m not the mind, I’m just the Self; and while I’m asking myself, the thoughts fall away and I feel peaceful again.”

A second later she adds: “I know I talk a lot, but spirituality is a subject I love. Unfortunately, I can’t really talk about it at my school in Australia, because my friends don’t understand and they’re not interested in meditation either, and at school we don’t have a meditation class that could teach them what it means. I like Australia, but if I had the choice, I’d prefer to live in India, because I see a lot more people meditating there, in temples, in ashrams, even in the streets, and I really like it!”

Meditation, then, can be practiced regardless of one’s age, religion, social background or walk of life. Only the approaches vary, with each person practicing what seems most suited to them. Let’s look at more examples of personal testimony from across the religious pantheon.

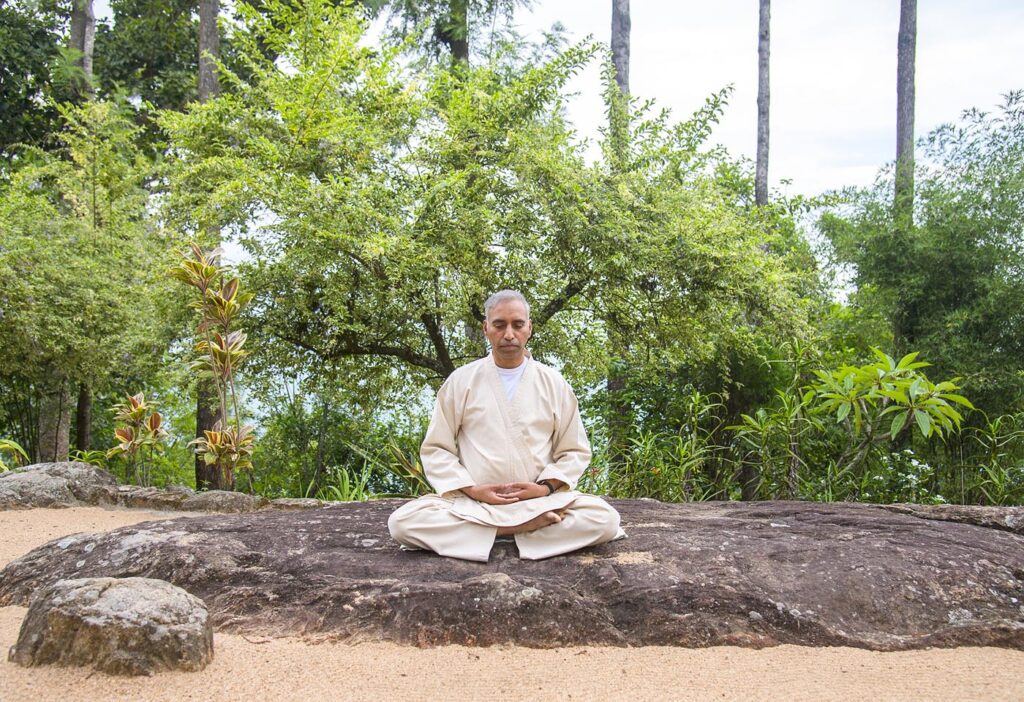

Chitartha Ellamnee Grube: “My spiritual name is Chitartha EllamNee. I was born 73 years ago in Germany. My name today was given to me several decades ago by our Guruji—Chitartha, chit meaning “consciousness,” and artha meaning “abiding in.” I led a mainstream life in the 1950s and ‘60s in Europe, but around the age of 30, I wanted to discover the world. I was particularly attracted to Asia, so I flew to Sri Lanka.

“During this trip, another traveler told me about a place one could do a Vipassana retreat. I thought this would be a good opportunity to learn more about meditation. This man made me promise to do the full ten-day retreat and not to leave before the end, no matter what. I promised—but by the end of the third day, I was ready to leave due to terrible body pains caused by sitting cross-legged on the floor for several hours a day. However, I stayed. My body slowly adapted, and it became a deeply peaceful experience. This Vipassana retreat, where I ended up spending three months, changed my life to such an extent that I even considered becoming a Buddhist monk. To this day, I cherish this time in my heart.

Anne Petry

“A Vipassana retreat lasts usually 10 days, during which you are asked not to speak, read, write or make eye contact with others. For the first three days, the focus is on the breath, concentrating on the tip of the nose and feeling the air flow in and out, or on the rising and falling abdomen. When thoughts, feelings or bodily sensations appear, you accept them, let go and gently bring your attention back to the breath. After the third day, we open our attention to whatever arises in the body-mind, observing the appearances and cessations of mind objects, without controlling or judging.

“While meditation began for me as a way of understanding how the body and mind work, I soon realized it actually gave me the wisdom not only to observe my thoughts and moods, but also to understand and manage them, leading to transformation.

“If I had to sum up Vipassana meditation in a few words, I’d say it’s a spontaneous, effortless, choiceless awareness. Vipassana is in fact more than just a meditation technique, it’s an attitude of mind and a training in mindfulness that can be practiced while eating, walking and in any other everyday task. Ultimately, Vipassana meditation enables us to live in the present, and the ongoing practice of this technique leads to an understanding of anicca, a fundamental notion of Buddhism that refers to the impermanence of absolutely everything and the fact that all existence is only temporary.”

Geetha Rubingh: “I was born just over 70 years ago in The Netherlands into a loving family who passed on great values to me. My father was a humanist, a true believer in the goodness of people. My mother was a Christian, but she rarely went to church; she preferred the Christian content to the institution itself. This was the context in which I was brought up, but when I left home at 16 to study, I abandoned all religious practice and belief.

“It wasn’t until I was 33, after a serious accident and a near-death experience, that I became interested in the spiritual world again. I first became interested in anthroposophy (Christian-based). Then I joined a Krishna-based ashram in The Netherlands for 23 years. Today, I live in India, and in my spiritual practice I focus on the all-pervading energy that is the creative life force (Purushottama) which I combine with mantra meditation. I learned to meditate over 30 years ago, and mantras have been the basis of my spiritual development. Etymologically in Sanskrit, mantra means ‘tool for the mind,’ a way of focusing and quieting the mind. My guru gave me some mantras, which I have repeated hundred of thousands of times, and I really felt a difference in my energy system.

“My meditation practice very often follows the same pattern. First, I relax my body, then I recite mantras for about 30 minutes. Once my mind is calm and concentrated, I let everything go and remain in silence with my attention totally within. If the attention slackens, I simply go back to reciting the mantras. There are recommended times for meditation (very early morning), and in this period of my life I can afford to meditate from 3am to 6am. But this isn’t the case for everyone, so it’s a question of finding the time slot that suits you best and then sticking to it. Also, there’s no point in forcing yourself to sit still, trying to achieve stillness if you’re upset, stressed or confused, as this can increase your restlessness. In the case of what might be called ‘monkey mind,’ I’d be more in favor of going for a walk in nature, put my awareness in the present moment, and simply being grateful for all there is. The power of gratitude leads to non-frustration, and only then one can fully enjoy a pleasant and peaceful mantra meditation.”

Shobha Surendran: “I was born 61 years ago in Kerala, South India. All on my father’s side were devout Hindu practitioners; but my mother, although she always helped people in need, didn’t believe in God. So when I was a child, the only reason I went to the temple was to play with my friends and get some prasad.

“As I grew up, I followed my mother’s beliefs. I became a fervent communist and a science teacher who only believed in what I saw. But eventually, life changes people. My mother, who had health problems, was introduced to kundalini yoga and the power of inner energy.

“While I was teaching in Saudi Arabia, I came home once and my mother told me about her ‘spiritual discoveries’ and the existence of God. Though highly skeptical, I decided to investigate the subject. Listening to my mother’s new insights and reading books such as Meta Modern Era, I was literally blown away! I felt as if a rocket had exploded in my head, destroying all my previous agnostic beliefs; I was entering a new dimension. That was about 30 years ago. To deepen my practice, I immersed myself in the teachings of Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi and Sahaja Yoga, a meditation technique and spiritual practice based on the experience of kundalini awakening—Self-Realization.

“While the subtle body is made up of numerous nadis (energy channels), Sahaja Yoga focuses primarily on three channels (left, right and center), seven main energy centers (chakras) and the primordial energy of kundalini. In Hinduism, kundalini is a form of divine feminine energy (or shakti), believed to be dormant in the muladhara chakra located at the base of the spine. Kundalini energy can be awakened through the regular practice of mantras, asanas, pranayama and bandha (internal mudras designed to lock vital energy into the body). Once activated, the kundalini is channeled upwards through the central channel (the sushumna), from the sacrum to the top of the head, progressing from each of the seven chakras to the next in order to harmonize them one by one. This process of ‘cleansing’ the subtle body is carried out in the central nervous system by vibrations—a cool or warm flow over the hands, over the head and around the body. The mastery and ascension of kundalini energy aims at Self-Realization, with the ultimate goal of becoming one with absolute divine energy.

“Although I felt that meditation to awaken the kundalini was my path, I was very impatient at first. Several times, I felt stuck and wanted to drop everything. Fortunately, each time, something or someone brought me back to my meditation practice; and, over time, I felt a change taking place within me. One day, I finally had that fabulous glimpse of Oneness that changed my life. But this immense insight only strengthened my desire to know more! I desperately wanted to understand better. This is when a sahaja yogi told me about Sri Ramana Maharshi and his very direct teaching. From that moment, my daily meditation became reflection on Ramana’s words, ‘Who am I?’ and ‘The Self is the only Truth.’ My mind slowly became more quiet, and the ego eventually began to fade away.”

Father Cyril Mathew: “I was born 52 years ago into a Christian family in what was then a small village in Tamil Nadu, India. I’ve been a Christian priest for 20 years and a Zen meditator for even longer. In fact, during my long studies to become a Jesuit priest there came a time when I was assailed by existential questions like, ‘Why am I doing this? Am I taking the right path? Why did I leave my home and family to follow this lifelong commitment?’ During this period, I lost sleep and inner peace; I clearly remember struggling without finding adequate answers to these deep questions.

“One of the chief priests, whom I considered a spiritual master, advised me to do a retreat at a meditation center called Bodhi Zendo, near Kodaikanal in South India. This was my first real encounter with Zen Buddhism, back in 2000. When I got there, I felt like I was home at last, and thought: ‘This is it! This is the place I’ve been looking for.’ With this clearly in mind, I continued to study to become a priest, but I also became deeply involved in the life of Bodhi Zendo by becoming a disciple of Father Amma Samy, the Catholic priest who founded the Bodhi Zendo Meditation Center. This gave me the opportunity to deepen my Zen practice.

“Once I was ordained, my superiors agreed to let me move to Bodhi Zendo to take over from Father Amma Samy, who was growing older. I can’t say everything was easy; I reached a point where I was terribly conflicted between Christianity on the one hand and Zen Buddhism on the other. But over time, a kind of integration took place, and I realized that I needed one as much as the other.

“In Christianity, there are different types of meditation. There’s visualization, which consists of taking a scene from the Bible and trying to experience this scene with all the senses as faithfully as possible; reflective meditation, which consists of reading an extract from the holy book and reflecting on the passage in question; there’s the rosary prayer, which is similar to saying mantras; and finally conversational meditation, in which we talk to God, listen to His response and slowly enter into a conversation with Him.

“Zen Buddhism is more down to earth and has two main components of meditation. The first might be called body awareness, in which we concentrate on breathing in and out, or scan our body by consciously reviewing every part of our anatomy. This type of meditation is designed to bring a certain peace of mind, and will help to appreciate the second aspect, called Shikantaza. Shikantaza is simply sitting with full awareness, welcoming the moment as it is, without judgment, and letting thoughts come and go without focusing on any of them. It’s a meditative practice in which you live 100 percent in the present moment, without forcing or expecting anything.”

Vijayalakshmi: “I come from a small tribal village called Uppuparai, located in the mountains near Kodaikanal. I don’t know my exact age, but I’m probably around 50, and I’ve always lived a simple life, as we all do in this part of India, which is still very rural.

“From an early age, I used to go out and work the land, but I really learned about gardening around 20 years ago, when I was hired to look after the gardens of a beautiful property. My co-workers and I have developed the habit of twice a week, during our lunch break, sitting down and meditating together. I mostly use this time to pray to my Hindu Gods. My days are long; I’m on my feet from 5am to 10pm, busy with my gardening work and then with my household tasks once I get home. So, I don’t have much time left over to sit and practice any other type of meditation.

“But a Westerner I once met made me realize that I actually meditate perhaps more than any traditional meditator. In fact, as I stand barefoot in the earth, caring for these flowers, vegetables and trees that I’ve learned over time to regard as companions, all my attention is for them, and I put all my dedication into what I do. Whether I’m pruning a rosebush, sowing new plants, watering flowers or covering vegetables with a tarpaulin in case of heavy rain, I’m thinking of absolutely nothing else but the plant I’m taking care of and of what I’m doing at this very moment. My mind is totally focused on each of my actions.

“It’s only when my job is done or when I have a bit of free time that the thoughts come back, making me think of certain health problems I’ve had in the past, hoping I can continue to do this work I love for as long as possible and, above all, hoping that my two sons and their families are doing well. Compared to these moments of worry and anxiety, I appreciate much more the calm and peace of mind I find when I concentrate on my every gesture towards the plants.

“It seems that what I’ve been doing naturally for 20 years or more—focusing 100 percent on my task in the present moment—is considered a meditation technique called ‘movement meditation.’ But in the end, no matter the name given to what I spontaneously do, the only thing I know is that after so many hours spent with the plants, living in the present moment, with a mind free of all thought, I leave work happy and at peace, and at a slow pace, I return to my village, perched higher up in the mountains.”

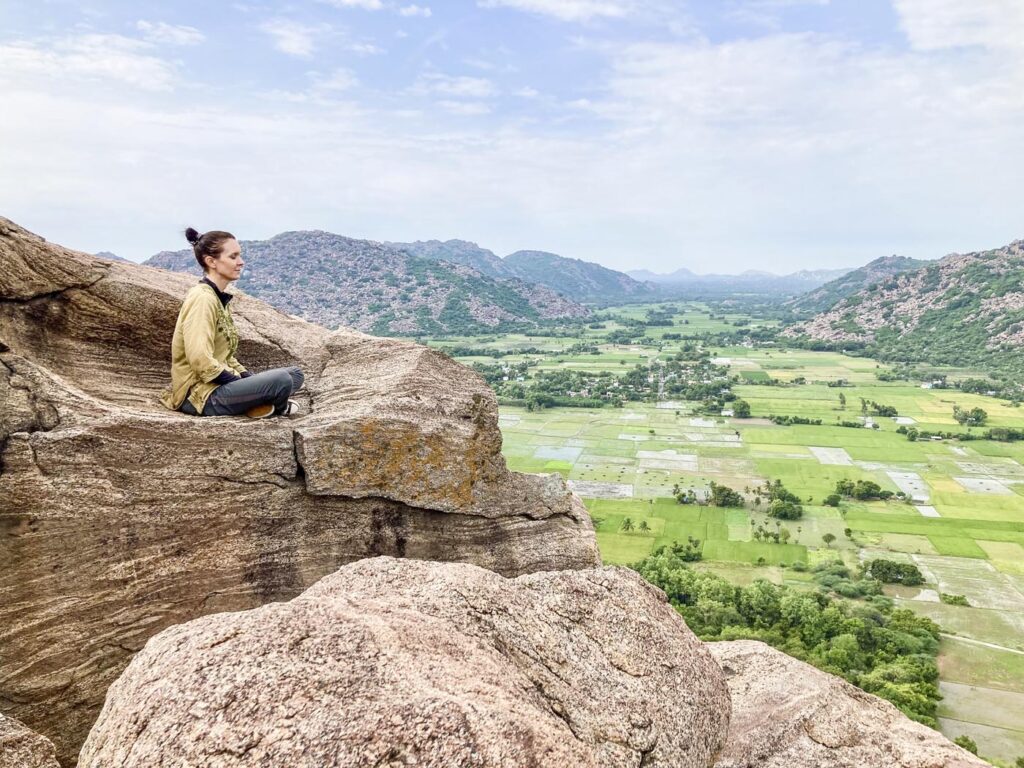

Marta Mattalia: “I was born in Italy, but for many years now I’ve been what you might call a nomadic musician. My parents traveled a lot; as a child, listening to them talk about their travels was very inspiring. In a way, it may have shaped my own life. So far, I’ve traveled extensively in Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and Asia, especially India, where I made my first solo trip six years ago.

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve always played music, but it was at the age of 14 that I started to learn and play music with more awareness. My encounter with Indian music began with Drhupad (Indian classical music) when I still was in Italy. But on that trip to India when I was 29, I heard for the first time a Parvathy Baul song and instantly fell in love with her voice, her music and, I think, her whole being. It took me a whole year and a one-way train ticket to Kolkata to finally find her and stand in front of her. The meeting was so simple and so beautiful that we both felt it was meant to be, and she agreed to take me on as a student and teach me Baul music.

“Baul is played with several instruments, but the main one is simply a fruit of nature: a calabash. It’s called ektara, which literally means ‘one string,’ and the sound it produces is what accompanies my voice. I created my own ektara, with a calabash and goatskin found in Kolkata, bamboo and wood found in Rajasthan. Perhaps because I made it with my own hands, for me the ektara is alive. When I talk about my instrument, I always say she and never it.

“Baul is an ancient form of music that originated in West Bengal, played by itinerant mystics who were something of outsiders, as they didn’t want to belong to any caste and created their own religious movement, a mixture of Vaishnavism, Sufism and Buddhhist Tantra. Baul music reflects this religious syncretism and, with its haunting lyrics, celebrates divine love and the yearning for unity with the Supreme.

“With my nomadic lifestyle, I don’t have a specific time to meditate and I don’t want to be a tyrant to myself. Instead, I go for a meditative walk in the forest, sit in lotus position by a waterfall or take my ektara out of her box and play. Also, my travels have brought me into contact with many different meditation traditions; so depending on what I feel, I create my own meditation, mixing practices and using what I need.

“I’ve always considered singing and playing music as part of my meditative practice, because as the music progresses, I feel my mind calming and concentrating. When I play Baul, my voice resonates even more deeply, I’m fully aware of the space around me, I feel totally connected to the world and I can say that I’m experiencing Oneness. This devotional music is also an extraordinary tool for communicating with others, for sharing the joy I have within myself and the love I have for life. Most of all, for me it’s an incredible meditative technique that allows me to truly feel the Emptiness that I am.”

Conclusion: In the course of my research I came to understand that all major world religions incorporate forms of meditation, even though many modern followers have lost touch with these practices. What I also found particularly beautiful was that, despite the fact that these religions have different names for God, their meditation techniques are remarkably similar, all centered on stilling the mind and the divine name.

Later, in my conversations with Geetha, Chitartha, Marta and the other people I approached for this article, I was fascinated by the number of different meditation techniques. Everyone chooses the method that suits them best, explaining that the choice of technique can vary according to their mood but, above all, according to the new insights they have gained over time.

For me, at this stage of my life, meditation simply means sitting quietly. Whether it’s in my veranda, my ashram or a bus station, the most important thing is to be present in the moment, to be aware of what’s going on around me and to accept everything: extraneous noises, flies tickling my arm or people moving next to me. I try to observe all this without judgment, without labeling experiences as pleasant or unpleasant. This is easier said than done, of course, and I’m no different from anyone else: some days my mind is calm, which makes meditation relatively easy, while other days my “monkey mind” jumps from one thought to another. But one thing I learned over the years is to meditate without looking for specific outcomes, accepting both the quiet and chaotic mental states equally.

This approach has become a powerful metaphor for life itself: accepting both the smooth sailing and the challenges, recognizing that it’s all part of the journey!