India’s Great Spiritual General

Written by Swami Advayananda, Brahmacharini Taarini Chaitanya & Sudarshan Ramabadran. Art by Sasi Edavarada, Gopi Chevayur & Ajithan from Thrissur

By Brahmacharini Taarini Chaitanya

I prostrate to adi shankaracharya, an incarnation of Lord Shiva, who is responsible for the welfare of the universe, who is the repository of the Divine Knowledge of Vedas, Upanishads and texts of the Purana and who is the embodiment of compassion.

श्रुतिस्मृतिपुराणानामालयं करुणालयम्।

नमामि भगवत्पादं शङ्करं लोकशङ्करम् ॥

śrutismṛtipurāṇānaṁ ālayaṁ karuṇālayam,

namāmi bhagavadpadaṁ shankaraṁ lokashankaram.

There exists no parallel to him, neither preceding nor succeeding his advent. Adi Shankaracharya stands as a unique fusion of seemingly contradictory attributes—a staunch traditionalist and an extraordinary radical, a captivating idealist and a grounded realist, a profound mystic and a pragmatic religious reformer, an unyielding intellectual and a fervent devotee. Within the span of his short life, merely thirty-two years, Shankaracharya accomplished feats that surpass the reach of even the most gifted individuals. His legacy is a synthesis of traditional wisdom and revolutionary thought, seamlessly blending timeless principles with innovative perspectives. His writings not only reflect the diversity of his character but also encapsulate the essence of his transformative vision, contributing significantly to the philosophical and spiritual heritage of humanity. The profound impact he made extends beyond the boundaries of conventional human achievements.

During the era of Adi Shankaracharya, Bharat found itself in a tumultuous period marked by profound philosophical and religious upheavals. A majority of the country’s populace had transitioned away from Hinduism towards Buddhism, contributing to a complex socio-religious landscape. Simultaneously, within the Hindu community, internal strife prevailed as various schools of thought engaged in philosophical contention. It was a chaotic period that required brilliant intervention. It was at such a time that Shankara was born.

Shankara’s parents, Shivaguru and Aryamba, were childless for many years. With utmost faith in the Lord, they undertook various austerities. On one pilgrimage they visited the Vadakkumnathan Temple in Thrissur, Kerala, propitiating Lord Shiva. That night Shivaguru was blessed with a dream-vision of Shiva. The Lord posed a question: “Would you like to have a child who is brilliant but will live a short life, or would you prefer a child of mediocre intelligence who will live long?” Shivaguru woke up and narrated the dream to Aryamba. Recognizing the sacred nature of the dream, the couple went to the temple early that morning. Their hearts full of humility, they bowed at the feet of the Lord and took a sankalpa: “O Lord, as suggested in the dream, please bless us with a child of great brilliance even though he would live a short life.”

Their joy knew no bounds and they returned to Shivaguru’s home at Kaladi in Kerala. Soon the child was conceived and, as per tradition, Aryamba went to her natal home, Melpazhur Mana in Veliyanad and remained there, worshiping in the ancestral temples until the birth of their son. Shivaguru named him Shankara (the bestower of goodness), in gratitude for Lord Shiva’s grace. Shankara showed remarkable intelligence from his early years; what others might take twelve years to learn, he was able to master in two years. Aryamba arranged for his vidyarambha (initiation into the study of the Sanskrit alphabet) in Melpazhur Mana, her maternal home. It is said that Shankara mastered the four Vedas by the age of eight—an indication of sheer brilliance. Unfortunately, Shivaguru passed away when Shankara was three. His wish to send his son to a gurukula, after performing his upanayanam (investiture of the sacred thread), was fulfilled by Aryamba at Melpazhur Mana.

Part 1: Illustrious Life & Accomplishments

By Brahmacharini Taarini Chaitanya

The youthful Shankara would often express his desire to take sannyasa and renounce the world. Aryamba ignored his earnest pleas. One day the boy was bathing in the Poorna River when he felt a tug at his feet. It was a crocodile that had taken hold of his leg and was dragging him to deeper waters. Facing death, he called out to his mother who stood on the bank, pleading to be allowed to take apat-sannyasa (renouncing in the face of death). Out of compassion, Aryamba reluctantly agreed, praying that he would survive. Shankara immediately recited the mantras to make a renunciate of himself. Miraculously, the crocodile released him and he emerged from the waters almost unscathed. Aryamba was now sure that this brilliant child was destined to do much more than stay at home and thus permitted him to walk the path of the holy mendicant.

Sensing concern in his mother’s heart, he asked if she had any wish that he should fulfill. A devoted seeker, Aryamba bestowed her heartfelt blessings upon her son. Not sure whether she would see him again, she uttered her sole wish—that upon her eventual departure from this earthly realm, Shankara would carry out her funeral rites. The boy assured his mother that he would be there.

In Search of the Guru

Thus, at age eight, Shankara began his arduous journey from Ernakulam to Omkareshwar in Madhya Pradesh—a path most uncertain, for he knew not where he was heading, whom he would meet on the way or how long it would take. Yet with complete faith in the Lord, he took to the path unknown. Enroute he met many people and there was much that the travel taught him, making his resolve to find his guru even stronger. Finally, on reaching the banks of Narmada, he knew in his heart he had reached his destination.

The mendicant’s longing for guidance and initiation was not in vain. It was in Govinda Bhagavatpada, a revered disciple of Gaudapadacharya, that Shankara found the guru he had yearned for. After much inquiry, he was directed to a small cave where Govindapada was immersed in deep meditation. With utmost reverence, the boy approached the cave. Careful not to disrupt the sanctity of the moment, he silently circumambulated the cave and then, with profound humility, prostrated before the entrance and recited prayers, extolling the virtues of the guru who resided within.

As the mahatma gradually emerged from samadhi, his eyes still closed, he inquired about the identity of the visitor. Without hesitation, Shankara spontaneously uttered the Dashashloki—his composition of ten profound verses—revealing not only his identity but also the timeless understanding that transcended the limitations of age and mortal existence.

“O guru, I am neither the earth, nor water, nor fire, nor air, nor space, nor any of their properties. I am not the senses and the mind even; for all these are transient, variable by nature. I am the One changeless essence, Shiva alone am I.”

The clarity and depth of the child’s answer left Govindapada overjoyed, exclaiming, “O child, I have been waiting for you over a lifetime and at last, here you are!” Moved by the earnestness in Shankara’s request to be initiated into Brahmavidya, Govinda Bhagavatpada initiated him into sannyasa. Thus Shankara joined the impeccable lineage that begins with Sage Parasara, whose son was Vyasa and grandson, Suka. Suka taught Gaudapada, from whom his disciple, Govindapada, learned all about Vedanta.

Govinda Bhagavatpada taught his student the import of the four mahavakyas from the Upanishads. Though Shankara may have already gained the crystallized essence of the Upanishadic teachings, Govindapada taught him the spiritual revelations and thought processes that lead to such conclusions.

The Madhaviya-Shankaravijaya states that Shankara once calmed a flood from the river Reva, thus saving his guru who was absorbed in samadhi in a nearby cave. After three years, to initiate him into the commentaries, Govinda Bhagavatpada gave him the task of writing a commentary on the Vishnu Sahasranama. Pleased with the exemplary work, the guru instructed his disciple to go to Kashi and begin the work of writing commentaries on the scriptures in order to propagate Advaita Vedanta. It is said that Govindapada thereafter sat in meditation and attained mahasamadhi. As per the customs, Shankara and other disciples immersed the Mahatma’s body in the Narmada River.

As directed by his guru, the 12-year-old Shankara traveled to Kashi. Contemplation, studying the scriptures and sacred literature, planning his works, spontaneous creativity, teaching the group of eager scholars around him, bathing in the Ganga and worshiping Lord Visvanatha marked his days in Varanasi.

A young man named Sanandana from Choladesha (present-day Trichy) became his first disciple. One day Sanandana was on the far bank of the Ganga when the guru called out to him after his bath from the opposite bank. Lost in his devotion, oblivious to the fact that the waters of the river had risen, keeping his guru alone in his vision, Sanandana walked towards Shankaracharya. Miraculously, with each step the man took, an array of lotuses rose to support him and he crossed the water. Indeed, the grace of the guru is a guardian amulet. Shankaracharya blessed him with the name Padmapada—the one with lotus feet.

It is not surprising that aspirants and youngsters thronged to the master. Apart from tutoring them, he engaged himself in writing down what he taught. It is said a major portion of Shankara’s prolific works were composed during his Kashi sojourn.

Composition of Major Works

In his long and difficult journey through forest tracks and mountain trails to Badrinath, the Acharya was accompanied by a few disciples. At Badarikashrama he recovered an idol of Lord Narayana from the bed of the Alakananda River and reinstalled it in the Badrinatha Temple with due ceremony. He also instructed that a Nambudiri Brahmin from Kerala should be appointed to conduct regular worship at the temple and prescribed rules for the puja. The tradition initiated by the Acharya then has been carried on and even now the priest there is a Nambudiri Brahmin from Kerala. It is an example of his efforts to rejuvenate Hindu religious practices.

This is where Adi Shankara’s synthesizing genius comes to the fore. Though young in years, he had already acquired vast experience in dealing with people from all stages of spiritual maturity, from all castes and classes. It became clear to him that very few could visualize the truth according to his vision of the eternal verity of existence: brahma satyam jagan mithya jivo brahmaiva na apara, “Brahman is the only truth, the world is an illusion and there is ultimately no difference between Brahman and the individual self.” Thus, Shankara did not reject the ritualism of the Vedic stream, as it imparts self-discipline and assures seekers that the life-divine is approachable. Religion, which offers images and elaborate methodologies of worshiping the Supreme in form, is needed as a step towards higher spirituality.

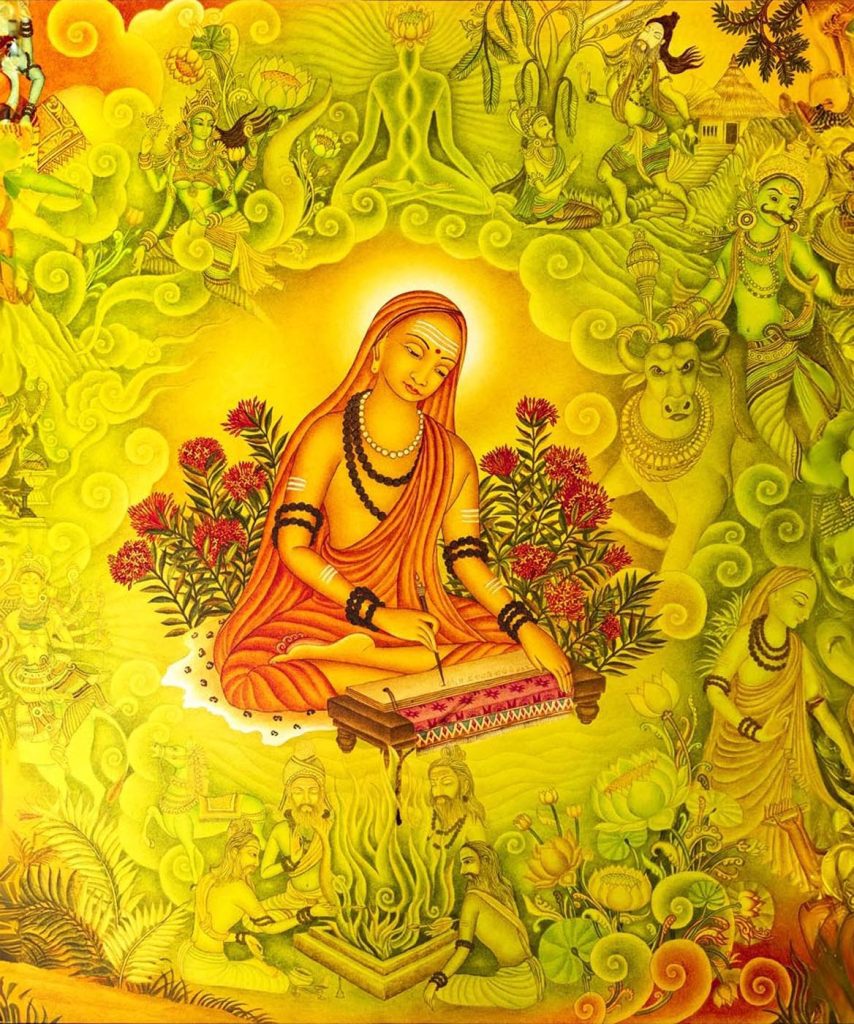

Shankara had come to the Himalayas in search of meditative silences so that he could write his commentaries on the Prasthanatrayi (the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, the Brahma Sutras) and treatises like Upadesa Sahasri. The Acharya also devoted time every day for teaching disciples, meeting visitors and religious leaders, clarifying their doubts and enhancing their knowledge. Madhava Vidyaranya mentions the tantrikas of the Pasupata sect, as well as followers of Gautama’s Nyaya philosophy, who were up in arms against Shankara. But the great Acharya was able to convince them of their folly by cogently arguing and establishing Advaita and the crucial principle of adhyasa, “false attribution.”

One night an aged Brahmin visited the Acharya and his disciples in the Himalayas. Welcomed with humility by the young sannyasin, the aged Brahmin raised several objections regarding the Acharya’s teachings. After several days of arguments and counter-arguments, Padmapada recognized Sage Vyasa in the visitor and brought the argument to a close with a humble and diplomatic intercession. Vyasa conceded that his ideals had been faithfully interpreted in Shankara’s commentaries. Shankara was sixteen years old at the time and about to complete his short life. Vyasa granted him a further extension of sixteen years to fulfill the mission of his life.

Trecking across Bharat

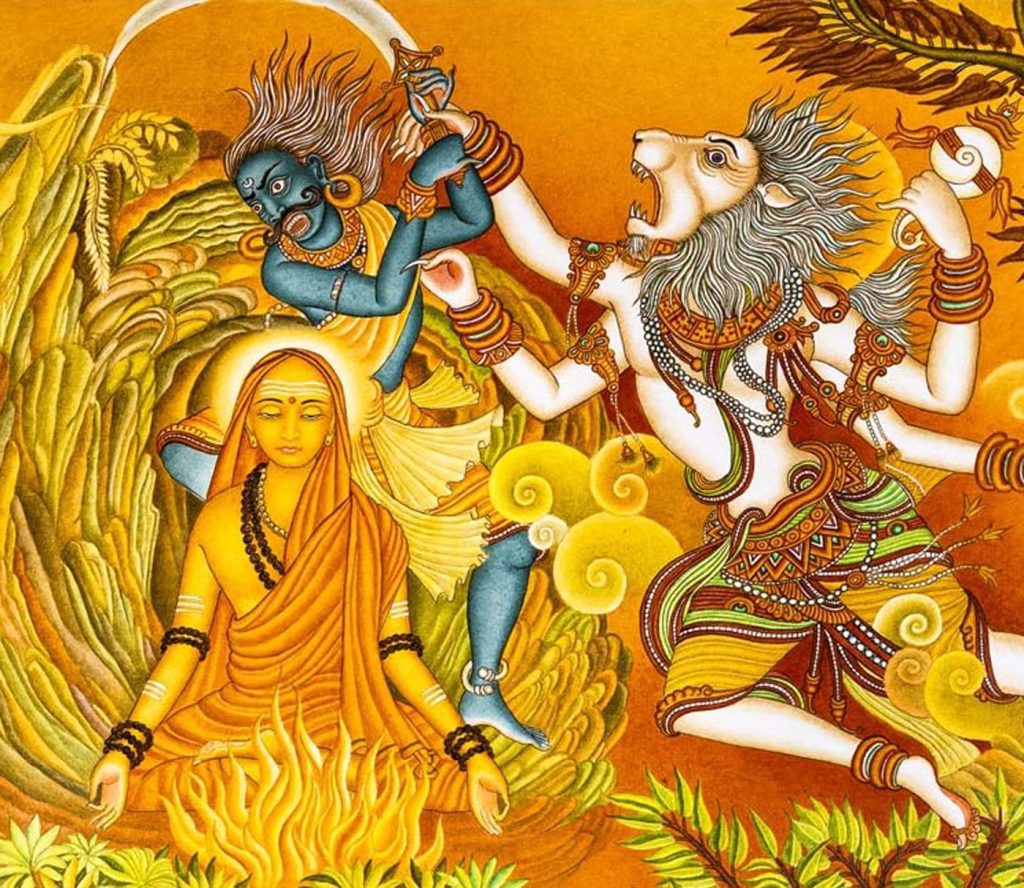

Shankara traveled with his disciples to Maharashtra and to Srisailam, where he composed Shivananda-lahari, a devotional hymn to Lord Shiva. On another occasion, when he was about to be sacrificed by a Kapalika, Padmapada’s prayer invoked Lord Narasimha to save Shankara, who then composed the Lakshminarsimha-stotra.

Next, he visited Sringeri to establish the Sharada Peetham. It was in Sringeri that Giri met him and went on to become an important disciple. A devoted student, Giri was ever engaged in serving the master. he was delayed for a class, but the Acharya decided to wait until his return. The special attention shown to the youth piqued some of the other students, who considered him to be average. When Giri arrived, a mere glance from the Acharya was sufficient to transform him. The young disciple burst out into a hymn in praise of the guru, an unstoppable rush of words in the totaka meter, which left the onlookers amazed. Here was a novice presenting a perfect hymn in a difficult meter, so full of lambent faith in the guru! Shankara was delighted and named him Totakacharya after the meter he had used for the hymn.

While at Sringeri one day, the Acharya suddenly learned of his mother’s illness and rushed to her side at her home in Kaladi. Aryamba had been hearing of his glories over the years and was exceedingly happy to see her son. She peacefully breathed her last in his presence. Acharya honored the promise he had made and, despite some criticism (swamis traditionally do not attend funerals, let alone conduct them), performed her funeral rites.

Digvijaya Yatra

After this, Shankaracharya began a digvijaya yatra—”victorious campaign in all directions”—for the propagation of the Advaita philosophy. He understood Bharat as one cultural unit, from the Himalayas to Kanyakumari and Kamarupa (Assam) to Gandhara (Afghanistan). He traveled on foot throughout Bharat, from the southern tip to Kashmir and Nepal, preaching to the local populace and debating philosophy with Hindu, Buddhist and other scholars and monks along the way. With the Kerala King Sudhanva as companion, Shankara passed through Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Vidarbha. Trekking through Karnataka, he reached Gokarna, where he defeated in debate the noted Shaiva scholar Nilakantha. Proceeding to Gujarat, he humbled Bhatta Bhaskara, the proponent of Bhedabheda philosophy in Dvaraka.

The Jains were defeated in philosophical debates at a place called Bahlika. In such manner, the Acharya established victory over several philosophers and ascetics in the region of North Kashmir called Darada. Later, he had an encounter with Navagupta, a tantrika, at Kamarupa (present-day Assam) who too accepted Shankara’s Vedantic teachings.

With his vision of cultural unity within Bharat, it was truly a digvijaya yatra—a triumphant tour annihilating the forces of ignorance and disruption, of consolidation and establishment of the unifying forces of universal brotherhood and understanding, culminating in the goal of all pursuits, the intimate experience of the non-dual Reality, no matter what paths are followed.

The Acharya came to know about a temple with four gates for Goddess Sharada in the Kashmir region. The temple was famous for its Throne of Omniscience (the Sarvajna Peetham), signifying that only an omniscient being can sit upon it. The temple had four doors for scholars from the four cardinal directions. The southern door had never been opened, indicating that no scholar from South India had ascended the throne. Shankara opened that door by defeating in debate in succession the scholars of various scholastic disciplines, such as Mimamsa and Nyaya. He then ascended the Peetham amidst victory cheers by his disciples.

Establishment of Mathas

Shankara founded four mathas (monasteries): Sringeri in Karnataka in the South, Dvaraka in Gujarat in the West, Puri in Odisha in the East and Jyotirmath in Uttarakhand in the North. He then dictated a book, Mahanushasanam, setting out the rules and disciplines to be followed in the administration of the mathas.

Tradition states that he put in charge of these mathas his four main disciples: Sureshvaracharya, Hastamalakacharya, Padmapadacharya and Totakacharya respectively. These four are often referred to as the “four pillars” or “four corners” of Shankaracharya’s spiritual order. Each of them contributed to the continuation of Advaita Vedanta, ensuring that Shankaracharya’s teachings were preserved and passed down through generations. The establishment of the four mathas in different regions of Bharat, each headed by one of these disciples, further facilitated the dissemination of Advaita Vedanta across the subcontinent.

Approaching the end of his life, Shankaracharya traveled by foot to the remote Himalayan area of Kedarnath-Badarinath and there attained videha mukti (freedom from embodiment). A samadhi shrine dedicated to the master is located behind the Kedarnath Temple. It is difficult indeed to summarize the life of the great Acharya who in a short life attained that which is immeasurable. To quote Pujya Swami Chinmayananda: Shankara is not an individual but an institution. Mastery over the four Vedas by his eighth year and all shastras by age 12, the Advaitic rendition of the Brahmasutras, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita by his sixteenth year—these were accomplishments impossible for an ordinary mortal. After thus living a visionary life of thirty-two years, the great saint and reformer merged into the eternal Truth. Jaya Jaya Shankara! Hara Hara Shankara! ∏π

References: Sankara the Missionary, Central Chinmaya Mission Trust; Adi Sankara: Finite to Infinite, Chinmaya International Foundation

Shanmata: Choosing an Ishtadevata

Raised and trained in the Smarta Brahmanical lineage, Adi Shankara arose to become the preeminent guru of that tradition, which is today one of the four major denominations of Hinduism, along with Saivism, Shaktism and Vaishnavism. His life redefined Hinduism forever. During this time, he promoted and revitalized the ancient Panchayatana Puja—a comprehensive and inclusive form of worship in the Smarta tradition that accommodates five Deities—Vishnu, Shiva, Surya, Ganesha and Shakti—allowing the devotee to choose a preferred Deity for personal devotion while recognizing the interconnectedness of all divine forms. It was his attempt to unify the prevailing sub-faiths of Sanatana Dharma: Ganapatyam, Shaivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism and Sauram.

The five are represented by small murtis, or by five kinds of stones, or by five marks drawn on the floor. One is placed in the center as the devotee’s preferred God, Ishta Devata, and the other four in a square around it. Kumara, often added as a sixth Deity, is generally situated behind the Ishta Devata. Each God may be worshiped in any of His/Her traditional aspects or incarnations, allowing for much variety (e.g., Shakti as Lakshmi, Vishnu as Rama, and Shiva as Bhairava). With the addition of the sixth Deity, Kumara, the system is known as shanmata, “six-fold path.” Philosophically, all are seen by Smartas as equal reflections of the one Saguna Brahman, rather than as distinct beings.

By formalizing this puja system, the Acharya has had a profound impact throughout the Hindu world, where it remains widely practiced in households and temples.

Debate with Mandana Mishra

After the long months of near isolation in the Himalayas, Shankara went to Prayaga in search of the renowned Kumarila Bhatta, a famous Purva Mimamsa philosopher, to debate their distinct philosophies. Unfortunately, when he met Kumarila Bhatta, he was sitting amongst smoldering fires as a prayaschitta (penance) for guru-droha (betraying one’s teacher). So, as directed by Kumarila Bhatta, Shankara approached his disciple Mandana Mishra at his home in Mahishmati and humbly sought a debate. Further, Shankara suggested that Mandana Mishra’s learned wife Ubhaya Bharati (an incarnation of Goddess Saraswati) should be the moderator of the debate. A condition was laid that the defeated person would give up their chosen path in life and take up the opponent’s path instead, that is, the householder would become a renunciate or the monk would enter family life. After debating for over 15 days, Mandana Mishra accepted defeat. Legend has it that Ubhaya Bharati then challenged Shankara to debate with her in order to complete the victory. This debate was to be on the subject of kama shastra (science of sensual love). But Shankara, being a renunciate from childhood, had no knowledge of this all-too-worldly subject. After requesting some time before entering into this fresh debate, he entered the body of a dead king by his yogic powers and acquired the requisite knowledge of kama shastra. Ubhaya Bharati, in respect for the acharya’s unparalled quest for knowledge, called off the debate and allowed her husband to take sannyasa. Shankara blessed him with the monastic name Sureshvaracharya.

Part 2: Shankara’s Philosophy & Teachings

By Swami Advayananda

.

The above title is a misnomer, for in truth Śrī Ādi Śaṅkarācārya propounded no new philosophy independent of tradition. After Śrī Veda Vyāsa, he remains the most significant proponent of Vedānta and so great has been his contribution that Vedānta has become synonymous with his name. Speaking about this colossus, Gurudev Swami Chinmayananda proclaims: “An exquisite thinker, a brilliant intellect, a personality scintillating with the vision of Truth, a heart throbbing with industrious faith and ardent desire to serve the nation, sweetly emotional and relentlessly logical, in Śaṅkara the Upaniṣads discovered the fittest spiritual general.”

Adi Shankaracharya’s Core Philosophy

What is Vedānta? The term Vedānta has two components: Veda and anta. Veda is the revealed scripture, the very foundation of Sanātana Dharma, and anta means end. Hence Vedanta is the end of the Veda. It refers to the Upaniṣads, which form the final section of the Veda. The Upaniṣads voice the philosophical message of the Veda and deliberate on fundamental existential questions—Who am I? What is the purpose of life? What is this world? Who created this world? If there is a God who created the world, what is my relation with God? Where is God? and so on—and conclude that the ultimate Reality, termed Brahman, is verily the Self, and the individual, world and God are Its apparent manifestations. In other words, the individual, the world and God, their Creator, are all but an appearance. In truth, all is but one and non-different from Brahman. This philosophical position is given the nomenclature Advaita (a-dvaita, no duality), the central message of which Śaṅkara expounds through all his works, directly or indirectly. Nevertheless, he founded no new system of his own.

Seminal Texts

What are the principal works authored by Śrī Śaṅkarācārya? To answer this, one needs to first know the foundational texts of the timeless Vedāntic tradition: (1) The Upaniṣads are held in the highest esteem as the foremost authority of knowledge; 108 of these are studied in the tradition and ten are considered the principal ones. (2) The Bhagavad Gītā, presented as a discussion between Lord Kṛṣṇa and Arjuna, God and man, systematically conveys the quintessence of the Upaniṣads and serves as a practical guide for comprehending and living the Upaniṣadic teachings in daily life. Arjuna is but a representative of each of us. When he is benumbed by his delusions and is about to veer away from the right course of action, God, man’s closest friend, destroys his doubts by bestowing upon him the supreme wisdom of the Upaniṣads. The battlefield here is symbolic of all our lives and thus the Vedāntic message of the Bhagavad Gītā is truly the panacea for the ills of life. Śrī Veda Vyāsa composed the Bhagavad Gītā, song of God, in his magnum opus, the Mahābhārata. (3) The Brahmasūtra, consisting of 555 aphorisms and authored by Śrī Veda Vyāsa, takes up for deliberation doubts and questions that could arise during the study of the Upaniṣads and resolves them through reasoning and debate. These three—Upaniṣad, Bhagavad Gītā and Brahmasūtra—form the foundation of Advaita Vedānta and are collectively referred to as Prasthānatrayī, the foundational triad. Śrī Śaṅkarācārya has blessed us with his elaborate commentaries on these works, which are at once both lucid and profound—bhāṣyaṁ prasannaṁ gambhīram. Such is the glory of these commentaries on the Prasthānatrayī that he is reverentially spoken of as Bhāṣyakara, the Commentator. A thorough study of these authoritative exegeses is essential for anyone wishing to delve deeply into Vedānta.

These principal works, however, would be difficult for a novice to start with. Śaṅkara, therefore, initiates beginners to Vedānta through the many independent preliminary texts that he has authored, both in prose and poetry, termed Prakaraṇa-grantha, including Tattvabodha, Ātmabodha, Aparokṣānubhūti, Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, Upadeśasāhasrī -and Sarvavedāntasiddhāntasārasaṅgraha.

In addition, Śrī Śaṅkarācārya’s foundational commentaries on the Prasthānatrayī, collectively called bhāṣyas, have themselves become the basis for further elaborations through ṭikās, or notes. Of these, the most significant is Ānandagiri-ṭikā, by Śaṅkara’s disciple Śrī Ānandagiri. Then there are also more extensive explanations of the bhāṣyas called vārtika: for example, on the Brahmasūtra–bhāṣya and on the Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad-bhāṣya and the Taittirīya-upaniṣad-bhāṣya. Many saintly scholars in the lineage of Śaṅkara have written independent texts to expand the core teachings of Vedānta, countless works indeed that have the single purpose of elucidating the message of oneness revealed by the Prasthānatrayī and by his commentaries. One can thus see the pivotal role played by Śrī Śaṅkarācārya in the Vedāntic tradition.

All these treatises—from the Upaniṣads to the Upaniṣad-in-spired texts, such as the Bhagavad Gītā and Brahmasūtra and the innumerable texts that further serve to amplify or explain the Upaniṣadic teachings—fall under the ambit of the umbrella term Vedānta.

Essential Teachings

The system of Vedānta progresses through six broad topics:

(1) Adhikārin

(2) Gurūpasadana

(3) Upadeśa, or teaching—the inquiry into:

1. Tvam-padārtha, or Self

2. Tat-padārtha, or Īśvara

3. Asi-padārtha, identity or oneness of Self and Īśvara

(4) Objections to identity and their resolution

(5) Sādhana

(6) Result

1. Adhikarin, the Qualified Aspirant

Success in any field of activity requires a prior capacity or an ability that forms the potential for accomplishment. In the spiritual realm though, since Vedānta is a subjective inquiry into the nature of the Self, the capacity here is more of fine-tuning one’s mind–intellect, the very instruments for the aforesaid inquiry. This fine-tuning of the personality reflects as (1) cittaśuddhi, purity of the mind and (2) cittaikāgrata, focus of the intellect. When both cittaśuddhi and cittaikāgrata mature, they manifest as sādhana-catuṣṭaya, or the fourfold qualifications -required to gain Self-knowledge.

While discussing the first aphorism of the Brahmasūtra, Śaṅkara emphasizes the four qualifications of a successful aspirant: (1) nit-ya-anitya-vastu-viveka, or the discrimination between the eternal and the ephemeral (2) iha-amutra-phalabhoga-virāga, or dispassion from the pleasures of this world and the other worlds (3) śama-damādi-sādhanasampat, the wealth of means beginning with śama and dama and (4) mumukṣutvam, or the desire for Liberation. In Vivekacūḍāmaṇi (verse 18) he asserts that only when these four are present will a seeker gain abidance in Reality, and when absent, the goal will not be reached.

The first qualification, viveka, is the discriminative knowledge that Brahman alone is permanent and everything else in the world of objects is impermanent. From a firm viveka follows vairāgya, dispassion, expressed as the absence of desire for any pleasure, be it of this world or of any other higher realm, such as heaven. Viveka and vairāgya impact one’s mind–intellect and flower as the set of six inner capacities: (1) śama, control of the mind; (2) dama, control of the senses; (3) uparama, cessation of extroverted activities; (4) titikṣā, forbearance in the face of the unavoidable pains and pinpricks of life; (5) samādhana, the ability to walk the spiritual path with focus and concentration and finally; (6) śraddha, faith in the scripture and the guru, the very means to accomplish Self-Realization. The six are collectively one, for the rise of even one of these supports the ascension of each of the others in the group. These are the true wealth of the seeker. When all these three—viveka, vairāgya and śamādiṣaṭkasampat—are perfected, there arises firm mumukṣutva, the burning desire for liberation, the fourth of the sādhana-catuṣṭaya, which then irresistibly compels the seeker to take the next significant step for spiritual progress, which is gurūpasadana. Verily, it is desire that propels any activity—be it secular or sacred! Thus, the sādhana-catuṣṭaya are the very foundation of spiritual pursuit.

2. Gurupasadana, or Surrendering to the Guru

It is a law of the cosmos that when one is ready for spiritual wisdom, the guru appears in the firmament of the seeker’s spiritual life. When the bud flowers, does not the bee discover it? So, too, when one yearns for spiritual fulfillment, the guru too is found. In fact, all one needs to do to find one’s guru is to evolve.

The guru from whom one can gain spiritual teaching is one who is both a śrotriya—one who has the comprehension of the śāstra—and a brahmaniṣṭha—one who is Realized. In other words, the guru is one who is himself rooted in the Wisdom that he can effectively expound to the student. Śrī Śaṅkarācārya presents in a few poetic brushstrokes a description of such an exemplary guru and the earnest student surrendering to such a master: “He who is well-versed in the scriptures, sinless, unafflicted by desires, a full knower of the Supreme, who has retired into the Supreme, who is as calm as the fire that has burnt up its fuel, who is a boundless ocean of mercy that needs no cause for its expression and who is an intimate friend of those who have surrendered unto him–worship such a guru with deep devotion, and when he is pleased with your surrender, humility and service, approach him and ask him to explain what you must know. …How do I cross this ocean of relative existence? What is my ultimate destination? Which of the many means should I adopt? I know nothing of these. O Lord! Save me and describe in detail how to end the misery of this life in the finite. …To him who, in his anxiety for liberation, has sought the protection of the teacher who abides by scriptural injunctions, who has a serene mind and who is endowed with tranquility, the master should pour his knowledge with utmost kindness.” Commenting on the importance of receiving the teaching from the guru, Śrī Śaṅkarācārya declares that no one, not even those well-versed in the scriptures, should independently pursue the knowledge of Brahman without the guidance of a teacher. The wisdom is subtle; it is about the very subject Self; and the mind is naturally extroverted; hence, an unguided inquiry into the Self is prone to be an utter failure.

3. Upadesha

Vedāntic teaching proceeds through the unique methodology of adhyāropa–apavāda, that is, deliberate superimposition followed by negation (adhyāropāpavadābhyāṁ niṣprapañcaṁ prapañcyate). To explain: we have the notion of being the body, mind and so on and also of there being a world independent and external to the self. On inquiry, we may posit a Creator or God, a cause for both the subject self and the object world. Vedānta proclaims that all three—self, world and God—are in truth the one Reality alone. Śaṅkara asserts: “I shall in a half-verse delineate that which has been explained in crores of treatises: Brahman is the Reality, the world is apparent and the Self is Brahman alone and not different from It.”

However, to come to this final comprehension, Vedānta first begins by giving credence to our notion of difference and starts the exploration of what these categories of jīva–jagat–Īśvara, or self–world–God really are. Giving these categories a seeming reality during the course of inquiry is termed adhyāropa; the culmination of the inquiry leads to the discovery that this triad is merely apparent and that in truth all are Brahman alone: this is termed apavāda, or negation. One recognizes all are one (ekam) alone (eva) and non-dual (advitīyam) (“ekam eva advitīyam”).

The dissolution of the false and the realization of the Self is enabled by statements such as “Tat tvam asi—That thou art,” “Aham brahmāsmi—I am Brahman” and so on, well-known in the tradition as mahāvākya, literally “great statements,” called so because of their emphatic proclamation that the individual and Brahman are one.

Every mahāvākya has three components: Self, God and their identity. For instance, in the mahāvākya “Tat tvam asi—That you are,” the word tvam, “you,” refers to the individual, the Self; Tat, “that,” refers to That which is the cause of the world, which is God; and the verbal component asi, “are,” asserts the identity of the Self and God. In Vākyavṛtti, Śrī Śaṅkarācārya explains in detail the mahāvākya Tat tvam asi.

“Brahman is the Reality, the world is apparent and the Self is Brahman alone and not different from It.”

3.1. Tvampadārtha—the signification of tvam, or Self: An object known cannot be the knower, the subject Self. The physical body, or the gross body, cannot be the Self, because it is an object of one’s knowledge, possessing qualities such as form and function. In the same manner, we are conscious of the subtle body, the mind, which is but a flow of thoughts, and also the prāṇa, which expresses itself in breathing, digestion and so on. In deep sleep, the state of the causal body, we are aware of the absence of all these, the pure ignorance of everything. All these are objects of my awareness. What I know, I am certainly not! If I am not the gross, subtle, or causal body, who am I then?

Know yourself to be that Witness–Consciousness other than the three bodies, in whose presence and proximity all the inert entities—the body, mind, senses, prāṇas and so on—function. Know yourself to be the illuminating Principle of the waking, dream and deep sleep states, the Seer that remains free of all changes or modifications. You are the dearest, for whose sake persons and things, such as children and wealth, all appear dear. Thus, the Witness–Consciousness, which is other than the body, mind, senses and prāṇas, the Existence that is free of modifications, is what is truly meant by the word tvam—you.

3.2. Tatpadārtha—the signification of Tat, or God: In the Chāndogya-upaniṣad, where the mahāvākya Tat tvam asi is taught, the word Tat, meaning That, refers to Sat–Existence, the ultimate cause of the world and the all-pervading Reality. The Upaniṣads describe That as verily the embodiment of Sat–Cit–Ānanda (Existence–Consciousness–Bliss), as neither gross nor subtle and as beyond the senses and mind. That is imbued with all-knowledge (sarvajña) and is all-power (sarvaśakti). In knowing That, all becomes known, for It alone pervades all objects as their very substratum and cause. It sustains all beings as their very self (jīvā) and remains as their inner-propeller (antaryāmin). That is also the bestower of the fruits of actions to all beings according to their actions (karmaphaladātā). In short, Tat—That—is Īśvara, God!

3.3. Asi-padārtha—or the identity or oneness of Self and Īśvara: We see ourselves as the individualized consciousness, associated with the mind–intellect and other conditionings, such as the body, senses and prāṇas. So, too, we consider God, with His Power (called variously śakti, māyā, prakṛti) as the Creator–Sustainer–Destroyer of the world, all-knowing and all-mighty. The mahāvākya Tat tvam asi—“That you are,” through the verbal component asi, are, declares the identity of the individual Self and God. In other words, what appears to be the inner, individual Self, the conscious being, is truly the non-dual Lord, of the nature of Bliss; and that Bliss is verily the individual Self.

By this teaching, the misconception of the Self being limited and God being distinct and distant to oneself ceases and one realizes one’s true infinite Self-hood, which had been hitherto veiled by ignorance.

4. Objections to Identity & their Resolution

How can Īśvara, God, the Creator–Sustainer–Destroyer of the world, and the finite, bound individual be identical?! This skepticism is natural. The declaration Tat tvam asi, through its verbal component asi, prods the seeker to go deeper and comprehend the true nature of oneself and Īśvara, for only in the context of their actual nature can there be this identity. The Upanishads repeatedly establish the identity of Īśvara and jīva by stripping them both of their relative associations. The differences between God and the individual are only due to the conditionings, and not with respect to their true nature. Īśvara is the Sat–Cit–Ānanda principle, associated with the macrocosmic conditioning of the causal māyā and the cosmic subtle and physical realms—because of which Īśvara appears as the all-mighty, all-knowing Creator–Sustainer–Destroyer of the world. The individual is also the Sat–Cit–Ānanda principle, but associated with the microcosmic conditioning of ignorance, mind–intellect, senses, prāṇa and so on, and appears to experience bondage and limitation, lurching between joy and sorrow ceaselessly. Sans these conditionings, both Īśvara and jīva are the one indivisible Sat–Cit–Ānanda principle. When the kingdom of the king and the shield of the soldier are both dispensed with, there can be neither king nor soldier!

It is these two contrasting standpoints, the absolute and the relative, that the Vedās articulate: Ajāyamāno bahudhā vijāyate—“Though unborn, He appears to be born manifold!” Being “unborn” is from the absolute or Reality standpoint. “Born” as the manifold world of objects and beings is from the apparent or relative standpoint. This means plurality is experienced but is not true; it appears but is not real: it is mithyā or māyā. Akin to a movie one sees—though experienced, it lacks reality, being but the play of light and shadow on a screen.

However, every illusion requires a substratum to present itself. On the changeless, indivisible, immaculately pure screen alone appears the movie, a veritable play of movement and sound. So, too, on the substratum of the Sat–Cit–Ānanda principle is the play of plurality consisting of Īśvara–jagat–jīva, that is God, the world of multiplicity and the infinite variety of individuals. They are all apparent, but what is true in them is the one indivisible Sat–Cit–Ānanda principle. Hence this unequivocal proclamation of the Upaniṣads: Ekam eva advitīyam—“One alone and non-dual.” This oneness or non-duality is Advaita!

5. Sadhana, or Means

How does one gain this direct realization or actualization of knowledge? The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (2.4.5) answers: Ātmā vā are draṣṭavyaḥ śrotavyo mantavyo nididhyāsitavyaḥ—“O Dear! The Self ought to be realized: should be heard of, reflected on and meditated upon.” These three: (1) śravaṇa, or listening (2) manana, or reflection and (3) nididhyāsana, or meditation—are the threefold practices for realization. Śravaṇa refers to listening and comprehending the Upaniṣadic teaching from a competent teacher to reach a definitive understanding of the identity of the Self and Brahman—to wit, “I am Brahman.” Next follows manana, which is to reflect on the teachings of the guru with reasoning, aligning the logic with the Upaniṣads so that a crystal-clear, unshakable comprehension arises: “I am indeed Brahman.”

It is observed that even after this intellectual comprehension that the Self is Brahman, there remain contrary notions of oneself being the doer and enjoyer and identification with the body, mind and other conditionings. This is due to the habitual identification with the not-Self over several lifetimes. Such identification does not immediately cease, and it is for dispelling this that nididhyāsana is recommended. The practice of nididhyāsana, or meditation, consists in abiding single-pointedly in the thought “I am Brahman,” and excluding all thoughts of oneself being the body, mind, senses, prāṇas, intellect and so on. As one remains absorbed in this firm knowledge that is already intellectually crystal-clear, the deep-seated contrary notions, termed viparīta-bhāvana, finally cease and ignorance is put to an end once and for all, just as medicine that is taken regularly destroys disease.

6. Phala, or Result

When ignorance ends, the results of ignorance—to wit, the identification with the non-Self—ceases and thus one is free of notions such as “I am a man/woman, noble/ignoble, saint/sinner,” and so on. Such an enlightened person is termed jīvanmukta, one who is liberated while living, who is free from individuality and the consequent sense of incompleteness by being ever established in the Self’s true nature of Sat–Cit–Ānanda, the indwelling formless awareness in all objects and beings.

The Upaniṣads state that the very moment one gains aparokṣa-jñāna, or direct knowledge of the Supreme, the knots of the heart, the ego and desire, are cut asunder, all doubts are dispelled and all karma shackles (from puṇya or pāpa—virtue or sin) are destroyed. This is the end of saṁsāra, or the cycle of rebirth. Such a jīvanmukta lives seemingly associated with the body, mind and other conditionings as long as the body’s destiny persists. Such a person is verily a blessing to the cosmos, for every action that emanates from him is only an expression of the Divine Will. And when this jīvanmukta’s physical body falls, the subtle body—the mind, senses and prāṇas—too resolves into its sources, the pañcamahābhūtas, or the five primordial elements. This dissolution of the subtle body, the substrate for individuality, whereby it permanently ceases to be, is termed videhamukti, or liberation at the fall of the body. Describing this, Śaṅkara declares: Upon the dissolution of the upādhis, limiting conditions, the sage is absorbed in the all-pervading, attributeless consciousness, like water into water, space into space and light into light.

Conclusion

Self-Realization is God-Realization. This is the highest triumph of the human and the noblest fulfillment, for gaining this one becomes kṛtkṛtya, or fulfilled. For this unfoldment one is ever grateful to the guru, for even though one has transcended the realm of plurality, this journey to the infinite would never have been possible without the guru. Such a mahātmā (great person) who has gained this realization is a benediction upon the world. He enables each one’s spiritual unfoldment; his very presence ennobles and enriches all, like the spring that bestows its gleam and joy on the entire world by its mere arrival. He is the very embodiment of the śāstra, for in him one sees the scripture lived and its veracity established. He is the walking–sitting–talking God, for in him what expresses is not the will of the individual ego but the will of the Lord. He is verily one’s own Self!

Quotes from Adi Shankara

The world, like a dream full of attachments and aversions, seems real until the awakening.

Do not be proud of wealth, people, relations and friends, or youth. All these are snatched by time in the blink of an eye. Giving up this illusory world, know and attain the Supreme.

Do not look at anybody in terms of friend or foe, brother or cousin; do not fritter away your mental energies in thoughts of friendship or enmity. Seeking the Self everywhere, be amiable and equal-minded towards all, treating all alike.

Knowing that I am different from the body, I need not neglect the body. It is a vehicle that I use to transact with the world. It is the temple which houses the Pure Self within.

Even after the Truth has been realized, there remains that strong, obstinate impression that one is still an ego – the agent and experiencer. This has to be carefully removed by living in a state of constant identification with the supreme non-dual Self. Full Awakening is the eventual ceasing of all the mental impressions of being an ego.

When your last breath arrives, grammar can do nothing.

The treasure I have found cannot be described in words; the mind cannot conceive of it.

You never identify yourself with the shadows cast by your body, or with its reflection, or with the body you see in a dream or in your imagination. Therefore you should not identify yourself with this living body either.

Shivananda Lahari

By Sri Adi Shankara, Translated by P. R. Ramachander

28. The Mukti of my becoming you is in thine worship.

The Mukti of my coming near you is in singing

About you and calling you “Hey Shiva” and “Hey Madhava.”

The Mukti of living with you is in sweet conversation

With thine devotees, who in their mind live with you.

The Mukti of forever mixing with you is in thinking

Forever of your moving and stable form which is the universe.

And so, I get all these in this birth itself,

O God who is the consort of Bhavani;

I am thankful to you for all these.

60. Just like the man dragged by flood longs for the bank,

Just like the tired traveler longs for the tree shade,

Just like the one who is afraid of rain longs for a pleasant home,

Just like the traveling guest longs for the sight of a hospitable householder,

Just like the poor longs for the charitable rich,

Just like the one terrified by darkness longs for the light,

And just like one suffering from biting cold longs for the open fire,

O my mind, you long for the lotus feet of Shambhu,

Which removes all fears and phobias and gives pleasure.

84. O Lord Shiva who rules all the world

And who is the friend of all the world,

O Lord who is ocean of bliss,

O storehouse of mercy,

To serve you beside your consort Gowri,

I am presenting you the maid of my intellect,

Who has all good qualities, with a request to you

To live in the house of my mind.

Part 3: His Twenty-First Century Influence

By Sudarshan Ramabadran

Sarvapali Radhakrishnan, statesman, author and former president of India, observed, “Adi Shankaracharya was not only a great thinker and the noblest of Advaitic philosophers, but he was essentially an inspired champion of Hinduism and one of the most vigorous missionaries in our country.” Dr. Prema Nandakumar, in her book Adi Shankara: Finite to Infinite, writes glowingly about how he contributed to knitting together the country with his pristine Advaita Vedanta philosophy, a philosophical thought propounding oneness in all. Shankara’s arrival on the scene redefined India’s spiritual history in myriad ways. His life redefined Hinduism forever. His contribution in such a short span of time added to India’s long-standing culture of inquisitive scholarship for spiritual seekers, academic researchers and students of theology, poetry, literature and philosophy. It is safe to say that he enhanced India’s civilizational continuance in the making of today’s modern nation-state.

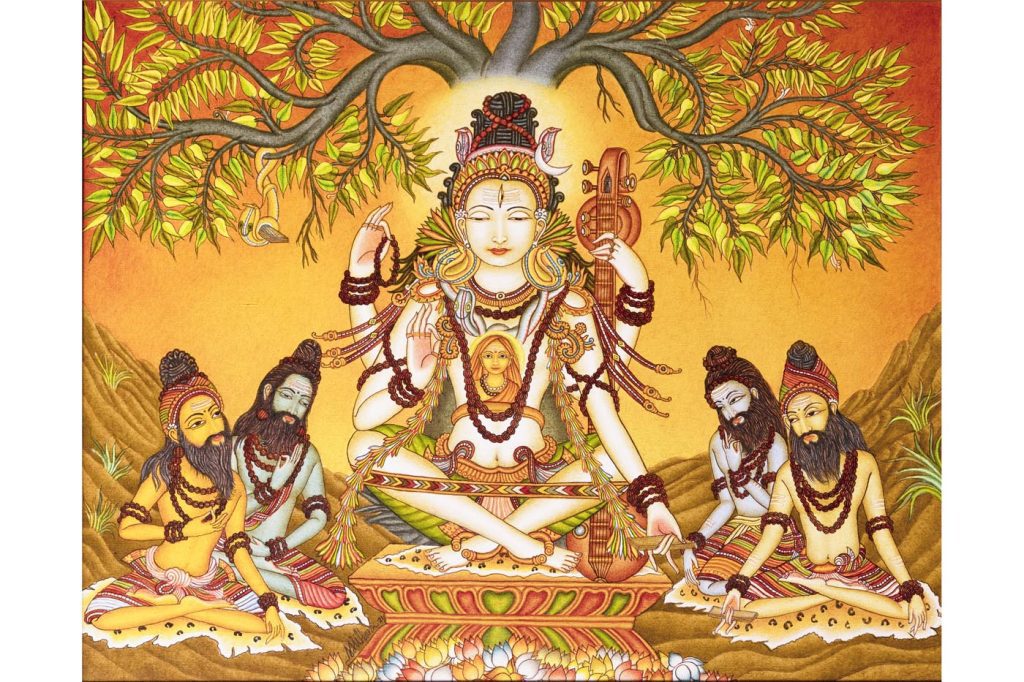

Scholars who have studied Shankara deeply have written about his contributions to stotra literature. His soul-stirring hymns like Bhaja Govindam, Soundarya Lahiri, Shivananda Lahiri, Kanakadhara Stotram and Dakshinamurti Stotram are all examples of how beautifully he sang about the impact of Deities all over India.

Through his own example and the establishment of pilgrimage sites and mathas, he promoted the practice of pilgrimage. Beginning at age sixteen, the young monk traveled by foot, arduously, across the length and breadth of India, not once but three times. In Atma Bodha, he wrote 68 verses about svatma tirtha, the pilgrimage to understand one’s own self which each one needs to undertake in life. In contemporary times, for policymakers and data consultants worldwide, monitoring and evaluation have become critical to understanding if an intended policy is to be successful. In the context of the individual, such monitoring and evaluation is essential. This is what Shankara’s svatma tirtha can be better understood as, a self-assessment that allows us to live with everlasting peace and happiness.

Working to Unite India

A strategic aspect of Shankara’s work was the establishment of monastic centers, or mathas, in the four corners of India. Twelve centuries later, these mathas are still carrying forward tremendous work for uplifting humanity in all spheres. Shankara is credited with reorganizing the sannyasins of his day into ten orders (Dashanami), each with a unique title: Sarasvati, Tirtha, Aranya, Bharati, Ashrama, Giri, Parvata, Sagara, Vana and Puri. He assigned them specific roles in upholding the scriptures. According to Choodie Shivaram (Tattvaloka, April 2012), “The Dashanami sampradayas, while nominally placed under one of the four mathas, maintained their independence, reflecting Shankara’s respect for diversity within the framework of unity. The mathas also served as a support system for wandering ascetics, providing them with a sense of belonging and purpose.” While the Dashanami monks associated with the Shankara mathas closely or loosely follow the procedures enumerated by Adi Shankara, there are innumerable other Hindu orders with different histories and beliefs that continue to affiliate themselves with mathas, ashrams and temples outside the ambit of the Dashanami sampradayas.

Policymakers in India are resolute that Shankara’s energy will help propel India forward on the path of progress and development. His timeless wisdom resonates deeply in contemporary India, reflecting a profound understanding of unity amidst diversity. Today numerous government-led enterprises support Ek Bharat Shreshta Bharat (“One India, Great India”), an intiative launched in 2015 by Narendra Modi to enhance the cultural connections between different parts of the country and to promote national integration. Events like the annual Kashi Tamil Sangamam and Saurashtra Tamil Sangamam celebrate the enduring connections between different regions, rooted in a shared spiritual heritage. Similarly, the Madhavpur Gedh Fair, held near Porbandar on the coast of Gujarat, commemorates legendary narratives while fostering cultural exchange. Today, India’s Ministry of Education is partnering with Indian universities to promote Shankara’s contemporary relevance. For instance, the Bharatiya Basha Samiti is organizing symposiums in Assam.

Influencing Spiritual Leaders

India’s history is replete with spiritual luminaries who have embodied Shankara’s philosophy. Swami Vivekananda stands as a towering figure in this regard, having represented Hinduism eloquently at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Vivekananda emphasized the unity of all religions, drawing inspiration from Shankara’s profound insights. He regarded the Acharya as one of the greatest exponents of Vedanta philosophy.

Similarly, Ramana Maharshi, hailing from Tamil Nadu, expounded the principles of Advaita Vedanta in his teachings. His profound insights on the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads have inspired countless seekers on the path to Self-Realization. Ramana Maharishi’s early Tamil translation of Adi Shankara’s seminal work, Vivekachudamani, attests to his deep reverence for the Acharya’s teachings and his commitment to elucidating them for contemporary audiences. To paraphrase, in his introduction he said that Lord Shiva, taking on the guise of Sri Shankaracharya, had come to guide humanity towards liberation, with Vivekachudamani serving as a roadmap.

Swami Chinmayananda, a modern stalwart of Advaita Vedanta, played a pivotal role in expressing Shankara’s teachings in the 20th century. Through initiatives like jnana yajnas and the establishment of Chinmaya Mission, Swami worked to make the profound wisdom of Vedanta accessible to all. His gurus, Swami Tapovan Maharaj and Swami Sivananda, had also furthered this legacy. Swami Chinmayananda was instrumental in buying the ancestral birthplace of Adi Shankara and instituting the Chinmaya International Foundation on the property in 1990. Institutions inspired and founded by these spiritual stalwarts continue to carry Shankara’s legacy into contemporary times, both domestically in India and globally. Mata Amritanandamayi of the Amrita Mutt, Sadhguru of the Isha Foundation and Sri Sri Ravishankar of the Art of Living are also carrying forward his foundational teachings. Their followings are significant and thus their influence is far-reaching.

Scholars and saints in India, among them Swami Chaitanyananda Saraswati of the Arsha Vidya Lineage, have increasingly drawn lessons from the life and teachings of Adi Shankara, particularly in the realm of governance and leadership, which revolves around the notion that genuine leadership transcends mere wielding of power or authority; instead, it involves serving others with humility and compassion. True leaders uphold dharma (righteousness) and exemplify qualities such as wisdom, strength and selflessness. By embodying these virtues, leaders can contribute to the creation of a just and equitable society in which the welfare of all individuals is prioritized.

Vedanta and Science

Renowned Indian jurist Nani A. Palkhivala hailed the sage as “one of the 12 greatest men who lived in a country at any age” and credited him with building an “empire of spirit.” According to him, “Shankara was a visionary who propagated a universal religion that underlies all religions.” He saw the saint’s teachings as profoundly aligned with modern scientific principles, noting that scientists like Sir James Jeans, Sir Arthur Eddington, Albert Einstein and Max Planck echoed Shankara’s assertion that the universe’s appearance differs from reality and that the ultimate reality is the spirit—the infinite spirit. Palkhivala posited that India had recognized this truth long before modern science articulated it.

at cif by ajithan

In 1990, Hinduism Today wrote of an International Congress of Vedanta organized in Ohio, USA, to mark Shankara’s 1,200th birth anniversary, in which several hundred scholars deliberated the interconnection of modern science with Advaita Vedanta. In 2023, an international conference, organized by Vedanta Bharati Institute of Yadatore Mutt, was held at Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh exploring the similarities between quantum physics and Vedanta.

As Dr. David Frawley aptly observes, Shankara’s vision remains a cornerstone of the Self-Realization movement worldwide, offering profound insights into the nature of reality and the path to liberation. Author and former diplomat Pavan K. Varma, in his seminal work Adi Shankara: Hinduism’s Greatest Thinker underscores the need to reexamine Shankara’s philosophy in light of modern physics. Varma’s exploration highlights the enduring relevance of Vedantic wisdom in an increasingly interconnected world, where scientific inquiry converges with spiritual insight. Subhash Kak, professor of computer science at Oklahoma State University, shared in an interview with me that one inspiration for quantum theory is Advaita Vedanta. “Philosophers of science generally accept that quantum mechanics is consistent with Vedanta. Indeed, the very inspiration for quantum theory, according to its co-founder, Erwin Schrodinger, was the Vedantic idea that the atman (microcosm) is equivalent to the cosmos (macrocosm). This gave Schrodinger the idea that the quantum state should be a superposition of all possibilities.”

Swami Mitrananda affirmed to me that Shankara’s concepts are being viewed through the prism of evidence-based modern science. He pointed to 2022 Nobel-Prize-winning scientists who posited that the “universe is not real,” particularly Alain Aspect, Anton Zeilinger and John F. Clauser. According to Swami Mitrananda, this aligns closely with Advaita Vedanta, which has long maintained that the world is not real and that the observer brings it into existence.

Quantum physics, as illustrated by the double-slit experiment, suggests that particles exhibit wave-particle duality and do not manifest definite properties until observed. Vedanta similarly posits that the universe emerges, exists and dissolves in consciousness, which is identified as Brahman. The universe exists because you see it. Today physicists are postulating that the world did not appear before it was observed.

Shankara was not the originator of Advaita Vedanta; he carried on the rishi tradition of guru parampara, starting from Veda Vyasa. It is his analyzing, dissecting, debating and communicating Vedanta for the benefit of the common man that sets him apart. Professor Kak noted, “Adi Shankara’s uncompromising questioning of the nature of awareness and consciousness is the reason his ideas are still relevant.”

Movies and Songs

Through expressions of popular culture such as movies and concerts, the life, thoughts and texts of Adi Shankara have reached a wide audience. A 1983 Sanskrit film by G.V. Iyer depicted the sage’s life, as did the 2013 Telugu movie Jagadguru Adi Shankara, which featured Nagarjuna and other Telugu film stars. The first recipient of the Bharat Ratna award in India (1998), M.S. Subbulakshmi, mesmerized audiences with her rendition of Shankara’s song “Bhaja Govindam.” She also showcased “Maitreem Bhajata,” a composition by Sri Chandrashekara Saraswati, 68th head of the Shankara Kanchi Math. Popular singers like Ranjani-Gayatri and Rahul Vellal, have sung many of Shankara’s devotional hymns, avidly watched on YouTube. The rendition of “Bhaja Govindam” by Gabriella Burnel, known as Gaiea Sanskrit on YouTube, has clocked 1.6 million views. She is one of the trendiest ambassadors of Indian culture. Other YouTube channels, such as Tattva Shankara, are spreading Shankara’s teachings in local languages. There is a movie in the pipeline on Adi Shankara slated to be released in 2025 by Ekatma Dham of the Madhya Pradesh government, spearheaded by Swami Mitrananda.

Ekatma Dham

India continues to erect prominent statues at significant places associated with the Acharya’s history. The government of Madhya Pradesh, under erstwhile Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan, established the Ekatma Dham project, featuring the remarkable 108-foot bronze “Statue of Oneness” in Omkareshwar, unveiled on September 21, 2024 (see photo on page 50). Today it is an integral part of the state’s tourism campaign. Omkareshwar, one of the 12 Jyotirlinga shrines of Shiva, is a highly revered Hindu pilgrimage site. The establishment of Adi Shankaracharya’s statue here links his Advaita Vedanta philosophy with the broader context of Hindu spirituality and the worship of Shiva. The complex aims to educate visitors about his life, philosophy and contributions to Hindu thought, as well as to promote his message of unity and universal consciousness. Over 23,000 villages in Madhya Pradesh contributed metals for the forging of the statue. The techniques employed to cast, transport and assemble the statue are testament to India’s modern engineering methods.

Alongside the statue, there is the Advaita Lok Museum on Adi Shankara. The Acharya Shankar International Institute of Advaita Vedanta is slated to come up there in the future, with centers named after his four disciples in the fields of Advaita philosophy, social science, science, music and the arts. Consider the youth initiative Advaita Awakening Youth Retreat, in which 50 youth delegations are given an introduction to the concepts of Advaita Vedanta and the Prakharna Granthas of Shankara. Teachers from spiritual organizations, such as Chinmaya Mission and Arsha Vidya Mandir, are guides for the retreats, which range up to 10 days each. Ekatma Dham covers all expenses, including boarding and lodging. Interested young seekers in Vedanta are encouraged to register for such retreats. Leaders and staff of Ekatma Dham include spiritual teachers from Sringeri Math, Juna Akhara, Vivekananda Kendra, Chinmaya Mission, Ramakrishna Mission and others. All these organizations are resolutely enabling this massive endeavor.

On into the Future

Today, the noble vision of Adi Shankara finds resonance in the compassionate endeavors of individuals dedicated to healing and service. One such beacon of hope is Sankara Nethralaya, “Temple of the Eye,” which commenced its mission in 1978. This remarkable initiative owes its existence to the visionary call of His Holiness Jayendra Saraswati, from the revered lineage of the Kanchi Sankara Math. In an enlightening article penned for the esteemed Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, Dr. Sengamedu Srinivasa Badrinath, the founding father of Sankara Nethralaya in Chennai, emphasized Nethralaya’s mission: to provide quality and affordable ophthalmic care to all, regardless of social class or caste, to infuse every endeavor with a missionary spirit and to perceive their workplace not merely as a clinical outreach, but as a sacred space where work becomes worship, carried out with sincerity, dedication and boundless love.

In these turbulent times of mistrust among nations and communities, in a war-ravaged world facing pandemics and their aftermath, it is vital to pivot to the teachings and thoughts of India’s spiritual general, Adi Shankara. Especially for the younger generation, there is so much to learn. By the age of 32, he was able to accomplish so much in life. Why cannot we each take up one challenge that confronts our society and work towards eradicating it, be it climate change or any public health or economic challenge? He set up so many institutions; it is the institutions that will produce competent individuals. One can take inspiration from him for envisioning long-term institutions that can benefit mankind and face the challenges that confront us as humans. Initiatives such as the “Walk of Hope” led by spiritual leader Sri M to promote interfaith harmony and peace, are espoused to further enhance the message of the sage’s teachings of universal love and oneness. India’s G-20 presidency in 2023 was themed “Vasudaiva Kutumbakam,” which means the world is one family, again aligning with Shankara’s philosophy.

For Shankara, every opinion mattered. In a structured and methodical manner, he put forth his points persuasively. Speaking of persuasiveness, he is an embodiment of soft power, which is a potent force in contemporary international relations. While there are many critics of soft power—the cognitive innovation enunciated by American political scientist Professor Joseph Nye in the 1990s—there is no denying that it has the ability to shape people’s preferences through policies, culture and values in a non-coercive manner.

Shankara, in his time, did this with aplomb, attracting like-minded seekers to Advaita Vedanta. While convincing others of his point of view, he never resorted to a single violent or even aggressive tactic. He simply, logically and effectively shared his philosophy of seeing one in all through the prism of Advaita Vedanta as an antidote to sectarianism and conflict. It would be an error to restrict India’s prodigy to just philosophy—he was a poet, a literary marvel, a theological genius and an exemplar of devotional practices. Today, through each of these prisms, he remains a source of inspiration for all.

Vivekachudamani

By Adi Sankaracharya, Translated by Swami Madhavananda.

6. Let people quote the scriptures and sacrifice to the Gods, let them perform rituals and worship the Deities, but there is no liberation without the realization of one’s identity with the atman; no, not even in the lifetime of a hundred Brahmas put together.

7. There is no hope of immortality by means of riches—such indeed is the declaration of the Vedas. Hence it is clear that works cannot be the cause of liberation.

8. Therefore the man of learning should strive his best for liberation, having renounced his desire for pleasures from external objects, duly approaching a good and generous preceptor and fixing his mind on the truth inculcated by him.

11. Work leads to purification of the mind, not to perception of the Reality. The realization of Truth is brought about by discrimination and not in the least by ten million acts.

13. The conviction of the Truth is seen to proceed from reasoning upon the salutary counsel of the wise and not by bathing in the sacred waters, nor by gifts, nor by a hundred pranayamas (control of the vital force).

15. Hence the seeker after the Reality of the atman should take to reasoning, after duly approaching the guru—who should be the best of the knowers of Brahman and an ocean of mercy.

81. Know that death quickly overtakes the stupid man who walks along the dreadful ways of sense pleasure; whereas one who walks in accordance with the instructions of a well-wishing and worthy guru, as also with his own reasoning, achieves his end—know this to be true.

82. If indeed thou hast a craving for liberation, shun sense-objects from a good distance as thou wouldst do poison and always cultivate carefully the nectar-like virtues of contentment, compassion, forgiveness, straight-forwardness, calmness and self-control.

Samadhi Sculpture in Kedarnath

After the historic floods of 2013 destroyed much around Kedarnath Temple, including the sage’s ancient samadhi shrine (where he left his body), Prime Minister Modi undertook to have a 12-foot statue carved for the site. The project was a collaboration between the government and various private organizations. Carved from chlorite schist stone by master sculptors from Mysore, the statue is designed to withstand the region’s harsh weather conditions at 12,000 feet above sea level, including rain, snow and sunshine.

Uttarakhand holds much significance with respect to Shankaracharya’s life, as he established one of the four mathas, Jyoshi Math, here in Chamoli district and also established the idol at Badrinath. India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, has been very active in preserving the legacy of Adi Shankara for contemporary India to understand and benefit from. He has encouraged all seekers to undertake travels following the trails taken by the swami across India.

The statue was unveiled and the Samadhi Museum inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on November 5, 2021. The museum celebrates the saint’s vast knowledge and qualities and stands as a testament to India’s rich cultural heritage. Visiting this site offers a unique spiritual experience, deeply intertwined with the rich tapestry of Hindu philosophy and the breathtaking natural beauty of the Himalayas.

Meeting the Chandala

One day, following a cool bath in the river Ganga at Kashi, Adi Shankara, Padmapada and other disciples were on their way to the sacred temple of Sri Vishvanatha. Walking through the narrow streets, he encountered a chandala (low-caste, “untouchable”) with a pack of dogs in tow. Inadvertently, Shankara uttered “gaccha gaccha—move away.” Unmoved, the chandala retorted sarcastically, “O best among the twice-born, by saying ‘move move,’ do you wish to move matter from matter, or do you wish to separate the pure awareness which is present here in me from the pure awareness present there in you? Is there any difference between the sun reflected in the water of the holy Ganges and that which is reflected in a dirty pool in the street of chandalas?”

Recognizing his folly, the acharya immediately fell at the feet of the man. Inspired by that casual encounter between a wise master and a lowly chandala in the narrow lanes of Kashi, Shankara spontaneously recited the famed Manisha Panchakam, a composition relating the four mahavakyas in brief and describing the glory of the guru who is not just the knower of Brahman but indeed Brahman alone. Shankaracharya declares that such a person—no matter how he appears and irrespective of his origin, caste, creed, nationality, status and so on—is his guru. Legend says it was Shiva who appeared as the chandala, and Shiva to whom Shankara prostrated.

Adi Shankara’s Birth Home

By Dr. Arundhati Sundar

To truly experience Adi Shankara Nilayam, go past the main entrance listening to the bird calls, strolling in the shade of the tall fruit and flowering trees, drinking in the fragrance, and enter into a quieter, more serene era. Look across the open, sandy yard at the 20-meter wide façade of the main illom (house) with its clay-tiled sloping roof. Off to the left is the Kulapuramalika (traditionally a guest house), and set back between the two is the Saraswati Sabha.

A large sign narrates the historical significance of this compound. Melpazhur Mana, the ancestral, maternal home and birthplace of Adi Shankara, is located in the village of Veliyanad in Kerala. It belonged to Sankaran Nambutiri, a descendent of Adi Shankara’s maternal family. He opted to release it to Pujya Gurudev Swami Chinmayananda, who established here in 1990 the Chinmaya International Foundation (CIF), an institute for Sanskrit and Indology research.

In those days the property was in a dilapidated condition. CIF undertook historical preservation of the three ancient structures, retaining the foundation and the walls, reproducing exactly the wooden frame, built without nails—a highly skilled, mathematically exact manual task currently practiced by few artisans.

The Mana is a four-winged structure (nalukettu) surrounding a central courtyard. The main entrance leads into a square room called the pumukham, with 108 lotuses carved into the wooden ceiling. Tall wooden pillars line the corridor around the courtyard. In the eastern section, close to the traditional kitchen and well, is the sacred room where Shankara was born. The mind becomes effortlessly meditative in the divine aura of this space, where an akhanda-jyoti (eternal lamp) is kept lit in front of the golden vigraha (icon) of Shri Adi Shankara. Local tradition has it that Adi Shankara’s vidyarambha (a ritual initiation in childhood to literacy) and upanayana (initiation to Vedic study) ceremonies were performed at Melpazhur Mana.

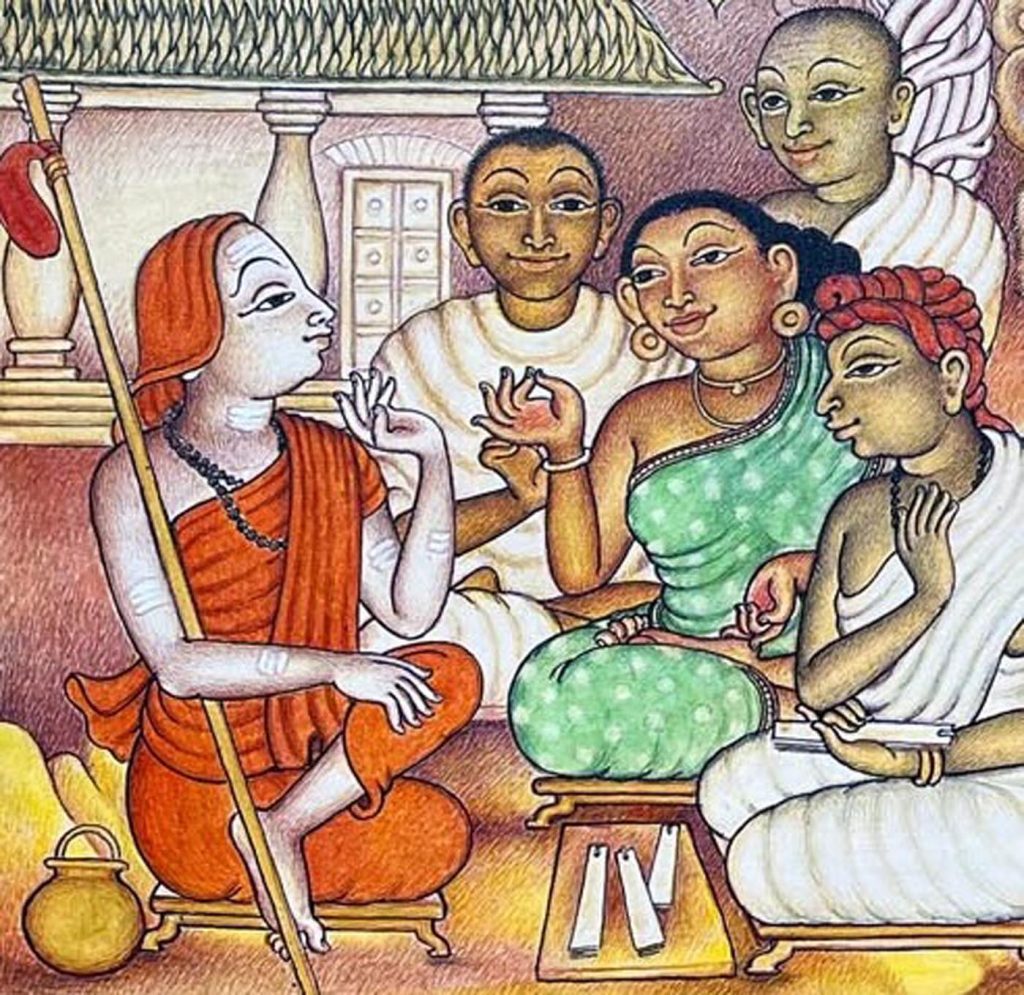

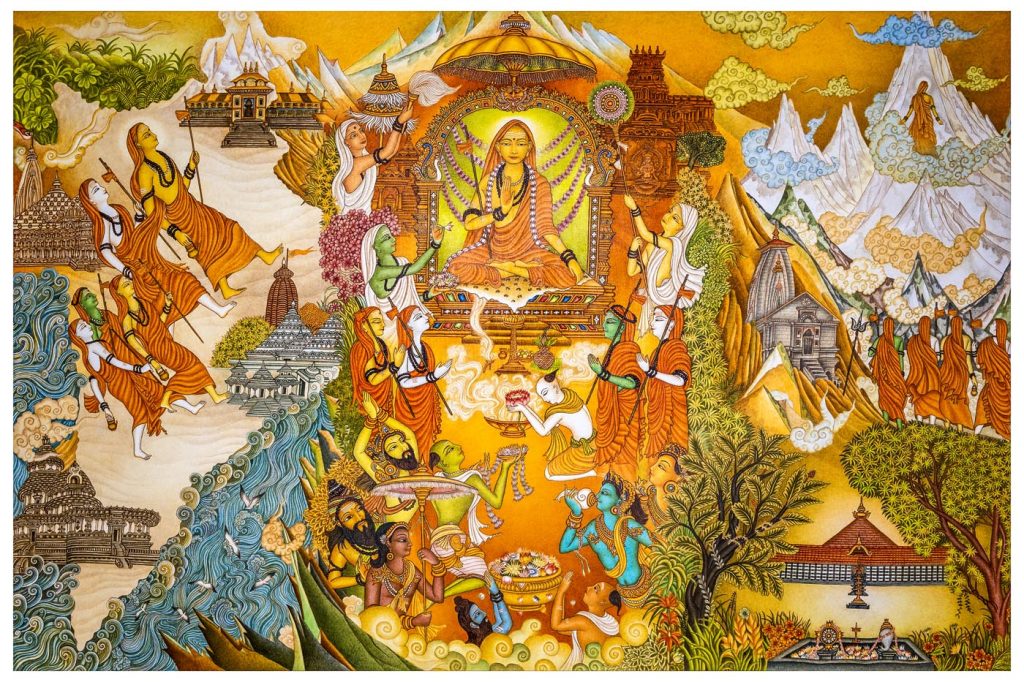

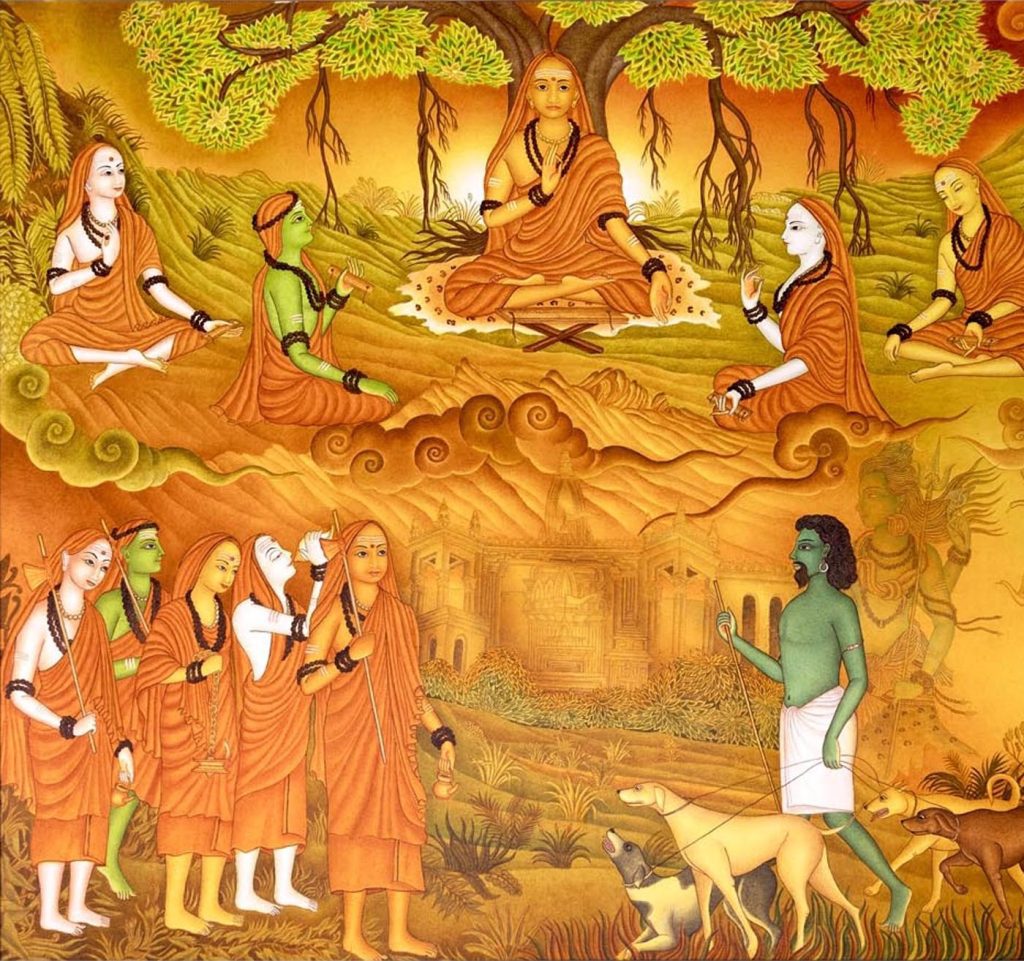

A fascinating glimpse into the life and works of Adi Shankara is depicted through the eight Kerala mural-style paintings by Shri Gopi and Shri Ajithan.

The precinct houses ancient temples to Deities—Vettakkoruvan (Kirata Shiva), Shri Nagayakshi and Bhuvaneshvari Devi—that were probably worshiped since before the time of Adi Shankara and his mother Aryamba. The Svayambhu Ayyappa Temple is comparatively recent, some 350 years old. The stairs lead down to the adjacent kulam (pond). At sunset on festive occasions, devotees light the 1,000 oil lamps surrounding the temple, with arati bells adding to the divine ambience.

Chinmaya International Foundation is a place of quiet contemplation, ideal for sadhakas and academics, with a library of manuscripts and Indic research books. It provides residential facilities for retreats and conferences (email: welcometocif@chinfo.org).

About the Authors

Swami Advayanand serves as Resident Acharya of the Vedanta Course at Chinmaya Mission’s Sandeepany Sadhanalaya in Mumbai, President of Chinmaya International Foundation and Trustee of Chinmayaa Vishwavidyapeeth (University), Kerala. He is an author of numerous insightful works on Vedanta and is an avid student/teacher of Vedanta.

Brahmacharini Taarini Chaitanya is a resident spiritual teacher at the Chinmaya International Foundation in Ernakulam, Kerala. She is deeply committed to serving Pujya Swami Chinmayananda’s vision to spread the eternal knowledge of the ancient Vedantic wisdom far and wide.

Sudarshan Ramabadran, author, policy expert and researcher, is an alumnus of the University of Southern California. In 2017, he underwent the Professional Fellow for Governance and Society, South and Central Asia Program in Washington, D.C., an exchange program run by the US Department of State. He also writes on mainstream and digital media platforms.

From time immemorial traditionally it has been accepted that Kalady is the birthplace of Adishankara Bhagavatpada. The popular Madhaviya Shankara Vijayam and many others of that genre have this idea. When such is the case where is the need to give an alternative narrative to that? Such narratives do not go to instil bhakti in Bhagavatpada. On the other hand, it will only create avoidable confusion in the minds of followers of the Shaankara sampradaya. It is better not to alter such deep rooted beliefs.