The Met showcases a Chennai artist who flourished in New York City

By Lavina Melwani, New York

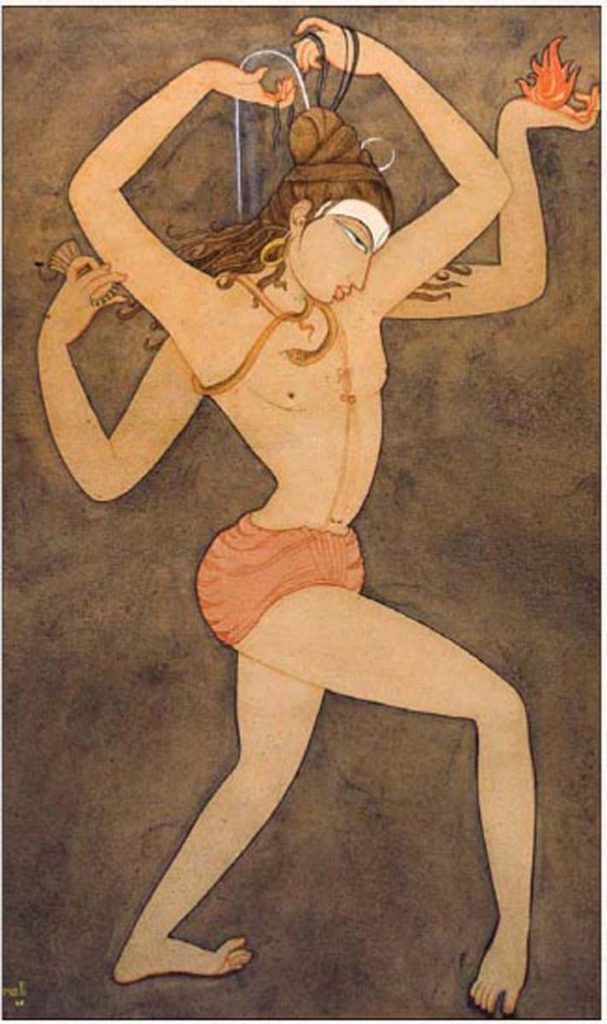

When Y.G. Srimati sailed from India for the West as a young artist in her 30s, she carried much more than could fit into any suitcase—the spirit of the mighty Shiva Gangadhara, Bearer of the Ganga; the blessings of Saraswati, Goddess of learning and the arts; the ragas which emanated from the vina, her beloved musical instrument, and a passion for the arts and culture of the Indian universe.

Born in a Tamil Brahmin family in 1926, she was the granddaughter of the royal astrologer to the Maharaja of Mysore. She left for foreign shores in the 60s but always carried a glorious India in her heart, mind and hands. This was all the more remarkable because she had grown up in the British Raj, where everything Indian was often stifled. Srimati was part of the nationalist movement for an independent India and actually spent time with Mahatma Gandhi, who profoundly influenced her way of thinking and the art she created.

Though Indian in spirit, she lived for 40 years in America, always telling the story of India’s religion and culture through her vibrant watercolors and her classical music and dance. Yet not many knew her story and her glorious work. She died in 2007 at the age of 81 back in her hometown of Chennai, but she spent most of her life in her New York home, a stone’s throw from the iconic Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Showcasing a Quiet Visionary

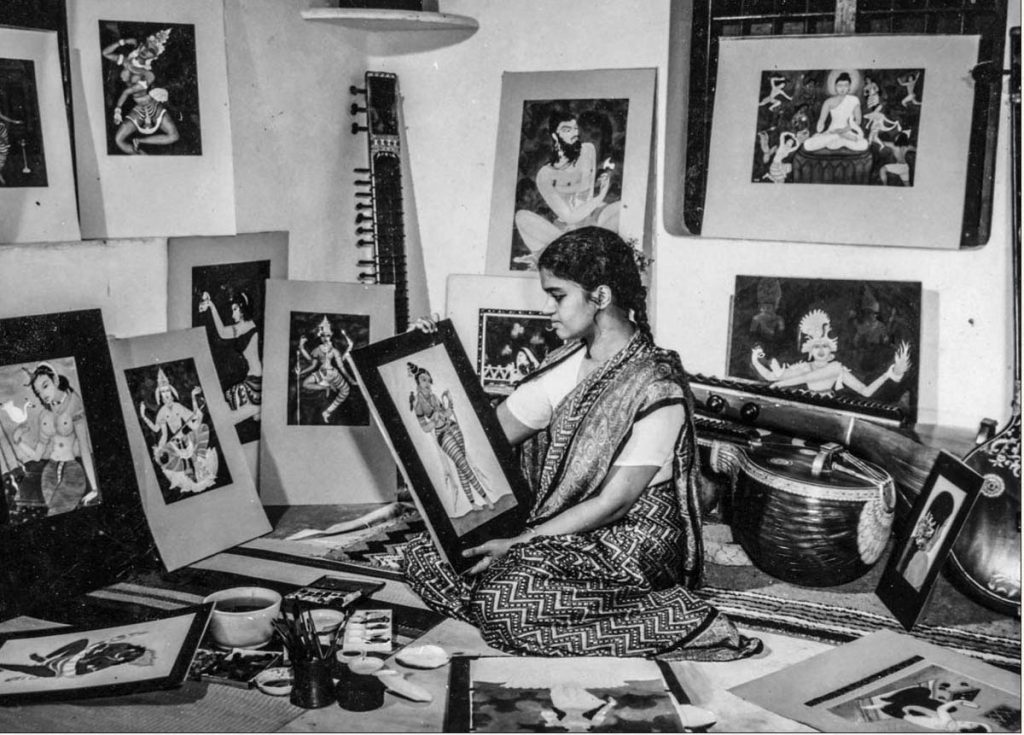

It is fitting that in December, 2016, the Met launched the first retrospective devoted to her little-known art, a small, jewel-like exhibition which ran through June 18, 2017. The exhibit, curated by John Guy, took several years to develop. It was drawn from private collections as well as The Met’s permanent holdings. Though focused on the first two decades of her career, it included works from her later periods. It featured twenty-five watercolor paintings, her musical instruments, archival photographs, and performance recordings.

“It is an exhibition which is really intended as a small historical corrective to re-establish the position of an artist who had really been forgotten.” said Guy. “Srimati’s painting displayed a consistent commitment to her vision of an Indian style. She explored themes from Indian religious epic literature and scenes of rural culture, asserting traditional subject matter as part of a conscious expression of nationalist sentiments; her choice was personal and idiosyncratic.… Through her highly controlled and softly modulated use of watercolor washes, Srimati built on the poetic and lyrical styles developed a generation earlier in India by Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose.”

Guy pointed out that her many roles of classical singer, musician, dancer and painter influenced and pollinated each other. He went on to explain, “Hers was a generation much influenced by the rediscovery of a classical Sanskrit legacy devoted to the visual arts, notably the ancient text on art, Chitrashastra, and the treatise of performing arts, Natyashastra.”

Early Life—a Multi-Faceted Talent

For Srimati, music, dance and art were as essential as life’s mundane necessities. Her father died when she was young, and she was raised by her older brother, Y.G. Doraisami, a serious patron of the arts in Chennai. Under his mentorship she learned classical dance, singing, instrumental music and painting. Even as a teenager Srimati was renowned in Chennai as a classical musician, dancer and vocalist. She had several solo shows in Chennai and Delhi, one of them presided over by India’s vice president.

Indeed, many volatile events made her follow the path she did. Writes Guy, “For the young Srimati, the explicit referencing of the past and of religious subjects came together in an unparalleled way, driven by the explosive atmosphere of an India in the final push to independence. This experience gave form and meaning to her art, and largely defined her style.”

As a young woman, she sang bhajans by Gandhiji’s side at many of his rallies. Even when she embarked on her Western journey, she carried with her a uniquely Indian perspective of art, music and the world. In 1959-60 she visited the UK, where she did solo shows and recorded vocal and instrumental works for the BBC.

She came to New York with a scholarship to the Art League in 1963. It was here she met fellow artist Michael Pellettieri, who later became her partner. After her passing, he donated some of her artworks and musical instruments to the Met. I asked him about her interests and he said, “She was both modest and charismatic, religious but open to universal ideas and music. Besides north and south Indian music, she loved the Beatles, Elvis Presley and Mozart.”

An Ambassador for India and America

In 1961, she was one of the early Indians to be granted a US visa based on special ability. In her later years she took American citizenship. In 1967 the Smithsonian Institution commissioned her to create an etching for the Geneva Peace Conference. Over the following years, she continued to paint, while also giving lectures and presenting concerts on college campuses across the US. Pellettieri recalled, “Most Indian musicians travel with a troupe, but she would travel alone, a suitcase filled with her paintings, instruments and her saris. In the 70s the Vietnam War was going on and there were a lot of protests on campus. She would always end her concerts with the simple peace invocation “Om Shanti Om,” which created a warm camaraderie with her audiences.”

Appreciating Srimati’s Art

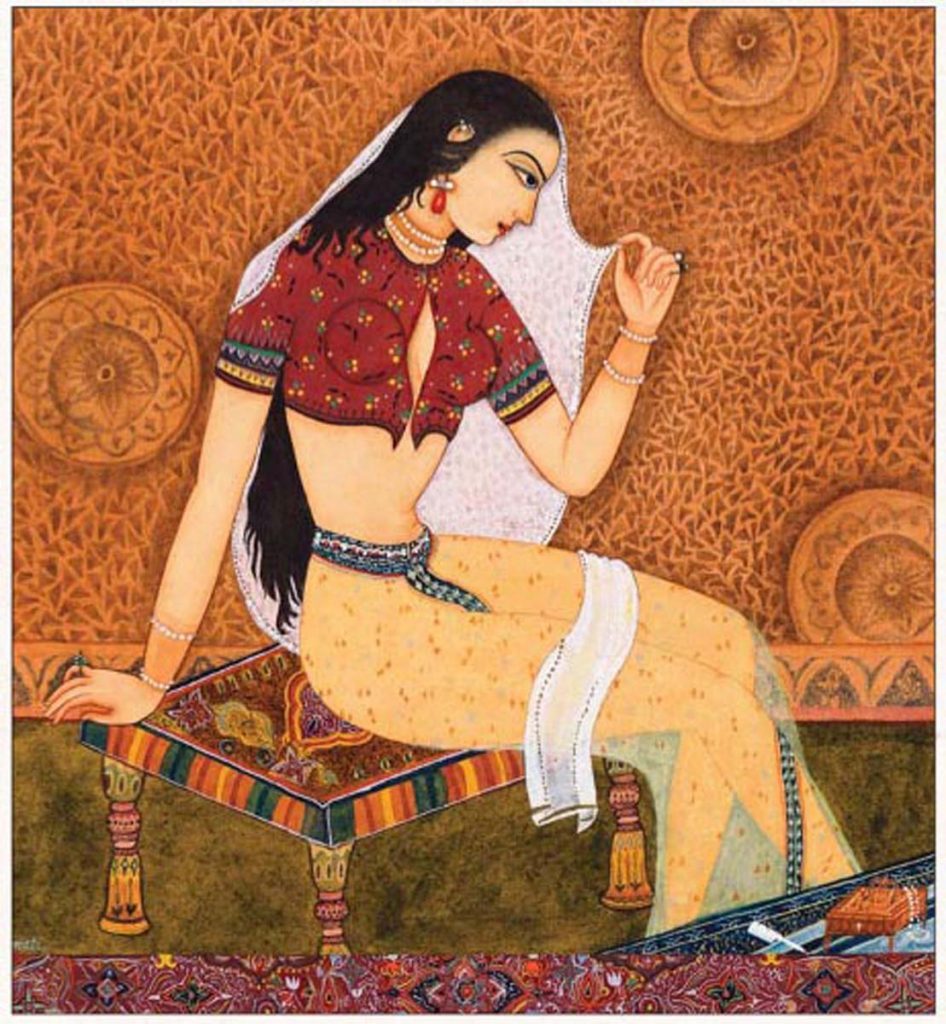

India remained the soul and breath of her paintings. In 1961 she worked on 15 commissioned paintings to accompany a deluxe edition of the Bhagavad Gita. It is in these powerful paintings that you see her strong Hindu beliefs. In an article in Orientations, John Guy touches upon the spirituality that imbues her art: “Among Srimati’s most successful early works were her explorations of subjects drawn from her deep understanding of Brahmanism and its rich imagery embedded in ancient literary sources, most notably the great religious epics and commentaries. Her choice of subjects was personal and idiosyncratic. These are fresh and original interpretations, clearly informed by her marrying of a passion for the sculptural qualities of Indian dance and a profound understanding of the spiritual dynamics of the subjects chosen.”

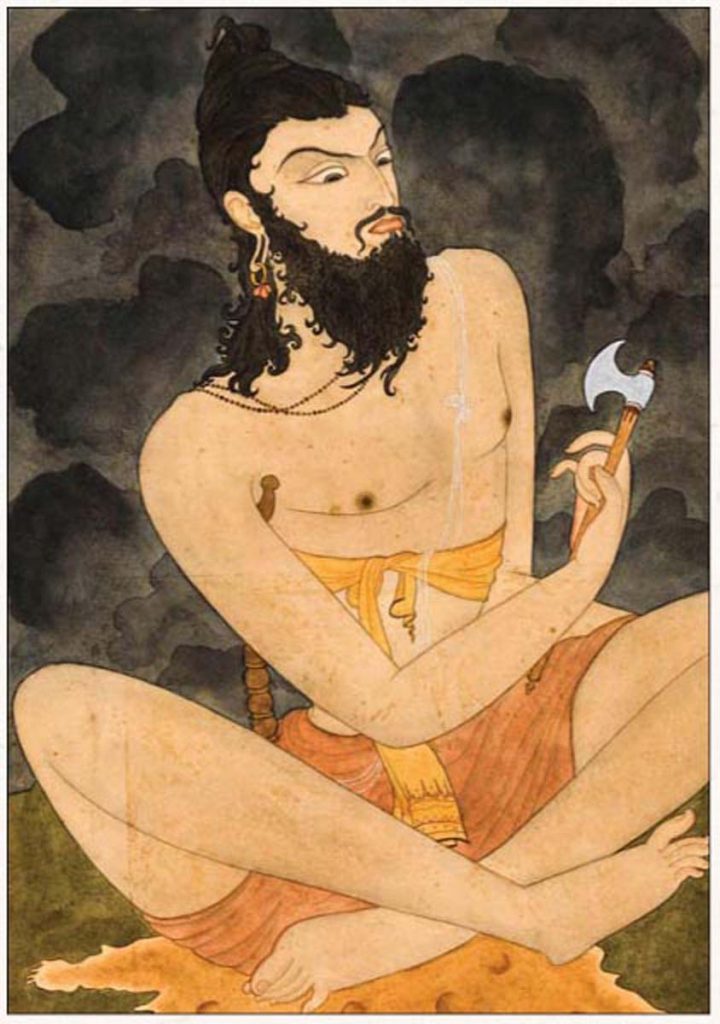

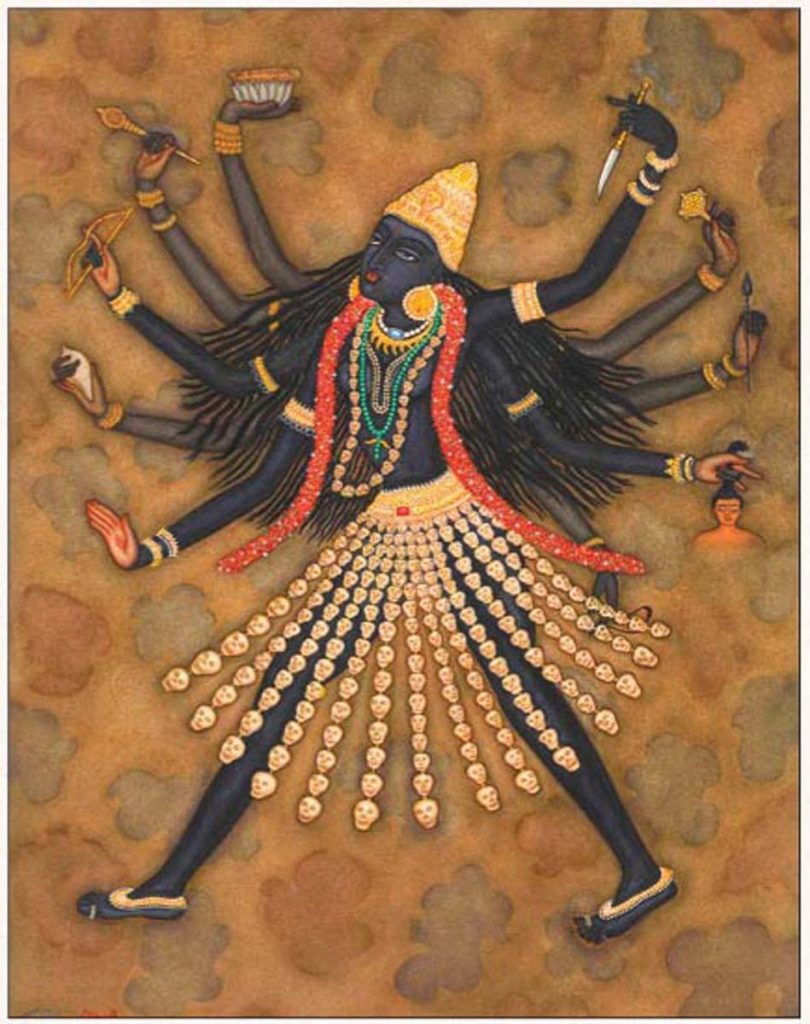

Shiva Gangadhara, Bearer of the Ganga (1945) is a powerful painting capturing the saga of Shiva holding back the flowing Ganges in His hair to safeguard the Earth. Yet another large-scale work from 1946 shows Parashurama with the Battle Axe, the sixth avatar of Vishnu. One of the most remarkable works is her watercolor of Mahakali (upper far right). Srimati wrote in her diary that she was awakened at night by the crushing sounds of the skulls in Kali’s skirt and kept hearing them until she finished the painting that encapsulates the power of the Goddess.

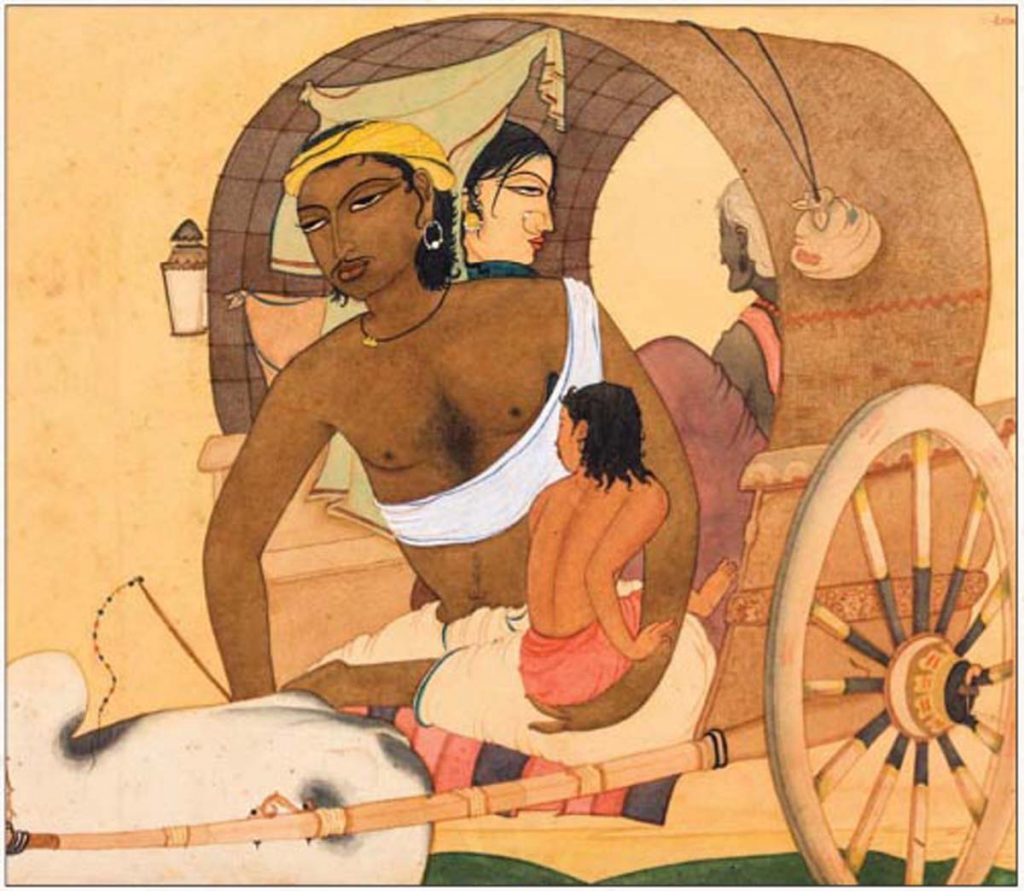

As the art critic Holland Cotter noted in the New York Times, “Ms. Srimati’s choreographic take on naturalism makes everyday subjects—a woman dressing, a family riding to market—look heroic, and images of deities and saints look approachably human. In the end, she’s a devotional artist, in the religious or spiritual sense: Her 1947-48 painting of the Hindu goddess Saraswati was originally displayed on her family’s home altar.”

A striking painting that brought music and devotion to Srimati’s canvas was Saint Tyagaraja Singing Hymns in Praise of Lord Rama (1952-55). In fadeout in the backdrop of the painting, almost like a heartbeat, you see Lord Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman, and even Sage Narada. Proclaims Guy, “This is devotional painting at its purest.”

A Gentle, Generous Soul

Srimati traveled back often to India often but made her home in America. She delighted in sharing her love of Indian art and culture with Americans, giving lectures and demonstrations. In her Manhattan apartment she cooked vegetarian food for her students and friends, introduced them to the music of the vina and gave classical Indian dance performances. In addition to her personal artistic expression through painting, vina and dance, she loved the opera and cinema.

Pellettieri recalls that she was always generous and encouraged ordinary people to perform informally at her home concerts. She was a great cook who shared her home-cooked meals, her art, music and dance with her guests. Her home in Manhattan was a salon for artistic evenings, just as her family home in Chennai had been.

Faithfully Hindu

“She was well-known in India, but once she came to the US she did not go back to exhibit,” he recalled. “She supported herself through teaching and commissions. Most of the time artists try to push their career—she just was not that kind of person. She took what came. She did not do self-promotion—she was very content painting in New York. She did her prayers and meditation every single day; she considered her work her worship.”

Indeed, devotion was a big part of Srimati’s life. On her trips to India, visits to the temples were a must. While many artists change their style to fit in with changing trends, Srimati remained faithful to the Indian tradition even when other artists had forsaken it. For her, the figurative style imbued with the spirituality of the past was not a style statement or a passing fad but an expression of devotion based on a profound belief system. ∏π