BY JANE SRIVASTAVA

All religions of the world extol compassion, yet they vary in their commitment to expressing this virtue through nonviolence and vegetarianism. A growing number of today’s vegetarians refrain from eating meat more for reasons pertaining to improved health, a cleaner environment and a better world economy than for religious concerns. Even those whose vegetarianism is inspired by compassion are oftentimes driven more by a sense of conscience than by theological principle.

In this article we briefly explore the attitudes of eight world religions with regard to meat-eating and the treatment of animals. It may be said with some degree of certainty that followers of Eastern religions–like Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism–generally agree in their support of nonviolence and a meatless lifestyle. But such a collective stance among followers of Western religions–like Judaism, Christianity and Islam–may not be asserted with the same confidence. Many deeply religious souls in the West eat meat because it is sanctioned in their holy books. Others refrain for a variety of reasons, including their sense of conscience that it is just not right, regardless of what scriptures say. Certainly, many scriptural references to food and diet are ambiguous at best. The issue is complicated.

Good Jains are exceptional examples of nonviolence and vegetarianism. Jainism, a deeply ascetic religion mainly centered in India, mandates that adherents refrain from harming even the simplest of life forms. Jains even follow dietary codes regulating the types of plants they eat.

Over the ages and around the world, Hindus have followed a variety of diets predicated on geography and socio-economic status. Although vegetarianism has never been a requirement for Hindus and modern Hindus eat more meat than ever before, no follower of this oldest of world religions will ever deny that vegetarianism promotes spiritual life.

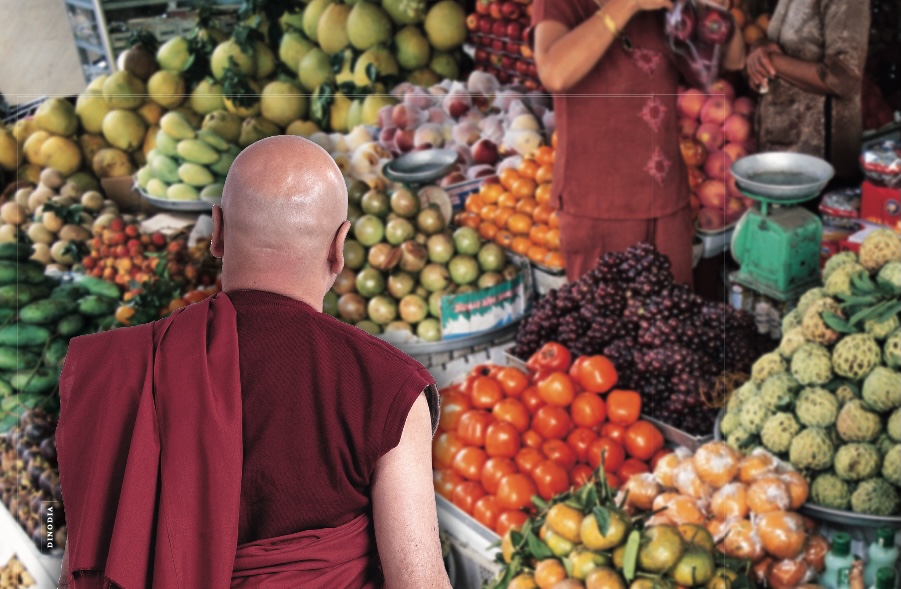

The dietary standards of Buddhists also vary in accordance with time and place. Although the cessation of suffering and an earnest commitment to nonviolence are central to Buddhist Dharma, most of the world’s Buddhists are not vegetarian.

In Judaism, the oldest of the Abrahamic religions, there has long been a debate over whether meat should be eaten, with the view predominating that God allowed meat-eating as a concession to human weakness and need.

Muslim cultures are predominantly nonvegetarian, though abstaining from eating meat is generally permitted if the devotee acknowledges that such abstinence will not bring him closer to Allah.

Modern-day Christians may eat meat without restriction. Even though many Christians of the Middle Ages were vegetarian, a meat-eating interpretation of the Bible has slowly become the official position of the Christian Church.

Here follows a study of perspectives on vegetarianism and nonviolence in these eight world faiths.

JAINISM

THE VIRTUOUS COMPASSION OF THE JAIN LIFESTYLE YIELDS EXEMPLARY VEGETARIANS

All good Jains are vegetarians, for they believe that no living entity should be harmed or killed, especially for food. According to one famous Jain motto: “All living creatures must help each other.” From its inception 2,600 years ago, Jainism has remained faithful in its commitment to nonviolence and vegetarianism.

Because followers of this gentle religion make compassion the central focus of their lives, their understanding and practice of ahimsa exceeds even that of many of the followers of other Eastern religions. Jains believe that humans, animals and plants are all sacred and can feel pain. Hence, they are careful to avoid harming even plants.

The concept of ahimsa, noninjury, permeates all aspects of Jain life. Some ascetics of this faith will sweep insects from their path as they walk and wear a face mask to prevent inadvertently killing small organisms as they breathe. Traditionally, these kindly souls adhere to the ideals of nonviolence with regard to the jobs they take to make a living. Often, they will work as traders of commodities. Even here, they follow rules. They will never handle goods made with animal products, such as hides, horns, ivory and silk. Farming and defending one’s nation are allowed as exceptions to the rule.

Jains classify the life-quality of all living entities according to the number of senses they possess. The lowest forms of life have only one sense: touch. This group includes plants. The highest life forms–including humans and most animals–have all five senses: touch, taste, smell, sight and hearing. The earthworm is an example of a life form with only two senses: touch and taste. Lice have three: touch, taste and smell. Mosquitoes have four: touch, taste, smell and sight. Jains consume only plants, because plants have just one sense.

Jains have extensive dietary rules regarding the choice and preparation of the plants they eat. Generally, vegetables that grow underground are prohibited, because harvesting them usually means pulling them up by their roots, which destroys the entire plant, as well as all the microorganisms living around its roots. When possible, fruits are plucked only when they are ripe and ready to fall to the ground. Ideally, these are harvested after they have fallen of their own accord.

Grains, such as wheat, rice and beans, are collected only when the pods are dry and dead. Very orthodox Jains will not eat certain fruits and vegetables that contain a lot of seeds–like eggplant and guava–because these so often contain worms. Cauliflower, broccoli and other vegetables with velvety surfaces are also avoided by orthodox Jains because tiny insects get stuck on their surfaces and cannot be removed. Mushrooms are not consumed because they may contain parasites. Leafy vegetables, like cabbage and spinach, are carefully washed and inspected for insects and worms. Dairy products are allowed.

Jains follow restrictions on the timing of food preparation and its consumption. Meals must be cooked and eaten only during daylight hours. This rule evolved because cooking food at night could cause the death of small flying creatures like gnats and mosquitoes that would be attracted to the light and warmth of a fire.

Jains perform several kinds of fasts, including during festivals and on the eighth and fourteenth day of the full moon cycle. While fasting, only foods prepared from grains are allowed, and no fruits or vegetables are consumed. Besides protection of other living beings, the primary purpose of the Jains’ dietary codes is to control desire and purify mind and body. In addition, their practices provide health and environmental benefits and help to conserve world resources. At a world environmental congress recently held in England, a comparative study of religions proclaimed Jainism the most environmentally friendly religion on Earth.

The lifestyle of modern Jain monks and nuns is more austere than that of even the strictest lay Jains. In their respect for Mahavira, Jainism’s founder, monks of the Digambar (sky-clad) sect wear no clothes, shave their heads and walk barefoot. They eat only once a day, and then only what is offered to them as a sacrament.

Today there are roughly five million Jains worldwide, with the most orthodox residing in India. Although many modern Jains modify their dietary restrictions for convenience, most are faithful vegetarians. Some have entered non-traditional professions. A select few have migrated to foreign countries and have become some of the wealthiest Indians in the world.

HINDUISM

HINDUS COMPRISE THE GREAT MAJORITY OF THE WORLD’S VEGETARIANS

The vast diversity of Hinduism’s multifaceted culture shines like gold in the variety of its numerous foods–both vegetarian and not. Geography, occupation, class and economic status play a significant role in determining the diets of modern-day Hindus. So does dedicated religious commitment.

Hindus are unmatched in their development of the art of enjoyable eating for healthy living. Their vegetarian food preparations are among the most varied in the world, and their ability to create a well-rounded nutritional diet without forfeiting taste is legendary. Many Westerners, inspired to be vegetarian but thinking a meatless diet might be boring or nutritionally lacking, derive renewed encouragement and inspiration from the many time-tested vegetarian traditions of India. One source of such wholesome eating dates back thousands of years to the health-care system of ayurveda, the “science of long life, “which utilizes food both as medicine and sustenance.

India’s cooking traditions vary greatly from North to South. One typical South Indian vegetarian meal might consist of an ample portion of rice centered on a banana-leaf plate, surrounded by small servings of vegetables prepared as curries, pickles and chutneys. This tasty assortment would be enhanced with soupy sambars and rasam, a few jaggery sweets on the side and a small portion of yogurt to balance the tastes and soothe digestion at the end of the entire meal.

Setting aside extenuating circumstances, most good Hindus would choose to follow a vegetarian way of life. All Hindu scriptures extol nonviolence and a meatless diet as being crucially important in the successful practice of worship and yoga. Most Hindu monastic orders are vegetarian. For centuries, Hindu temples and ashrams have served only vegetarian food. “Hindu dharma generally recommends vegetarianism, ” notes Vedacharya Vamadeva Shastri, “but it is not a requirement to be a Hindu.”

The earliest scriptural texts show that vegetarianism has always been common throughout India. In the Mahabharata, the great warrior Bhishma explains to Yudhisthira, eldest of the Pandava princes, that the meat of animals is like the flesh of one’s own son, and that the foolish person who eats meat must be considered the vilest of human beings. The Manusmriti declares that one should “refrain from eating all kinds of meat ” for such eating involves killing and leads to karmic bondage (bandha). The Yajur Veda states, “You must not use your God-given body for killing God’s creatures, whether they are human, animal or whatever.” The Atharva Veda proclaims, “Those noble souls who practice meditation and other yogic ways, who are ever careful about all beings, who protect all animals, are commited to spiritual practices.”

Over 2,000 years ago, Saint Tiruvalluvar wrote in the Tirukural (verse 251): “How can he practice true compassion who eats the flesh of an animal to fatten his own flesh?” and “Greater than a thousand ghee offerings consumed in sacrificial fires is to not sacrifice and consume any living creature.” (verse 259)

Vegetarianism, called shakahara in Sanskrit, is an essential virtue in Hindu thought and practice. It is rooted in the spiritual aspiration to maintain a balanced state of mind and body. Hindus also believe that eating meat is not only detrimental to one’s spiritual life, but also harmful to one’s health and the environment.

Most Hindus strive to live in the consciousness that their choice of foods bears consequences, according to the law of karma. Even the word “meat, ” mamsa, implies the karmic law of cause and effect. Mam means “me ” and sa means “he, ” intimating that the giver of pain will be the receiver of that same pain in equal measure.

Historically, while a large portion of ancient Hindu society lived predominantly on a vegetarian diet for religious reasons, certain communities, like kshatriyas (the Hindu warrior class), consumed at least some meat and fish. Hindu royalty also ate meat. Nomadic Hindus, who did not farm, had to rely on animal flesh for food, because nothing else was available. Agricultural communities were among the best examples of Hindu vegetarianism, for they were not inclined to kill and eat the animals they needed for labor.

All animals are sacred to Hindus, but one stands out among all the rest–the cow. According to an ancient Hindu story, the original cow, Mother Surabhi, was one of the treasures churned from the cosmic ocean. The five products of the cow (pancha-gavya)–milk, curd, ghee, urine and dung–are considered sacramental.

Although no temples have ever been constructed to honor the cow, she is respected as one of the seven mothers–alongside the Earth, one’s natural mother, a midwife, the wife of a guru, the wife of a brahman and the wife of the king.

Some controversy exists with regard to the Vedic interpretation of meat-eating. The the earliest of the Vedas, the Rig Veda, mentioned the consumption of meat offered in sacrifice at the altar, but even such ceremonial meat-eating was an exception, rather than a rule. Vedic offerings primarily consisted of plant and dairy products, such as ghee, honey, soma (an intoxicating plant juice), milk, yogurt and grain.

According to Vedacharya Vamadeva Shastri in his book, Eating of Meat and Beef in the Hindu Tradition: “Animal sacrifice (pashu bandhu) is outlined in several Vedic texts as one of many different possible offerings, not as the main offering. Even so, the animal could only be killed while performing certain mantras and rituals.”

Today, according to a recent survey, 31 percent of all Indians are vegetarian. Meat is not even sold or allowed in certain famous pilgrimage locations like Haridwar and Varanasi, and many non-vegetarian Hindus abstain from eating meat on holy days or during special religious practices. Most Indian states have a legal ban on the slaughter of cows, and beef is only available in non-Hindu stores and restaurants.

They who are ignorant, though wicked and haughty, kill animals without feelings or remorse or fear of punishment. In their next lives, such sinful persons will be eaten by the same creatures they have killed. Shrimad Bhagavatam, (11.5.14),

BUDDHISM

BUDDHA CONDEMNED MEAT-EATING, BUT ADVISED HIS MONKS TO ACCEPT THE FOOD THEY WERE SERVED

Like Jainism, Buddhism has earned well-deserved distinction for its ideals of nonviolence and compassion. Although animal sacrifice and meat-eating were common practices during Buddha’s lifetime, the sage opposed animal slaughter and advised his followers to not eat meat under the following three conditions: if they saw the animal being killed; if they consented to its slaughter; or if they knew the animal was going to be killed for them.

As Buddhism spread around the world, many of its fundamental concepts were modified to fit changing times and different cultures. The concept of ahimsa acquired a less stringent interpretation, and meat-eating among Buddhists became more and more commonplace.

Today, the international Buddhist community is divided on the issue of vegetarianism. The Dalai Lama himself is not vegetarian. Many Buddhists feel that it is acceptable to eat meat if someone else does the killing. Those who believe in the vegetarian ideal assert that killing animals is avoidable and does not resonate with Buddhism’s spirit of reverence for all life.

All Buddhist schools of thought agree that compassion and the cessation of suffering lies at the core of Buddha’s teaching. But there are conflicting interpretations even regarding Buddha’s own consumption of meat. While at least one tradition declares that Buddha died from eating tainted pork, a number of nineteenth-century scholars asserted that it was a poisonous mushroom that caused his death. Most Buddhists favor the latter explanation.

Buddha did not teach vegetarianism in a formal way. In one scriptural verse, he made it clear that a Buddhist monk should receive with gratitude any food that was put into his begging bowl, even if it were meat. It is almost certain, however, that most Buddhists giving food to a monk would know that offering meat would not be proper.

The Buddhist view of animals is best described in Jataka Tales–stories Buddha himself is said to have narrated. These anecdotes tell of his previous incarnations as animals and as humans. They convey the message that all creatures are divine, and that slaying an animal is as heinous as killing a human.

The two prominent Buddhist traditions today are the Hinayana and Mahayana sects. Those of the Hinayana sect, most of whom are renunciate monks, seek spiritual liberation through the attainment of Self-realization. The Mahayana sect, by far the largest school, is comprised mainly of family men and women who pursue spiritual advancement through service–helping themselves by helping others. The Indo-Tibetan and Zen traditions, which are of the Mahayana sect, have many texts that praise the vegetarian ideal.

A good example is found in the Lankavatara Sutras, a central Mahayana scripture said to consist of Buddha’s own words. In support of vegetarianism, the sage states: “For the sake of love and purity, the bodhisattva should refrain from eating flesh, which is born of semen and blood. For fear of causing terror to living beings, let the bodhisattva, who disciplines himself to attain compassion, refrain from eating flesh. It is not true that meat is proper food and permissible to eat. Meat-eating in any form, in any manner and in any place is unconditionally and once and for all prohibited. I do not permit it. I will not permit it.”

A Buddhist Bible, written by in Dwight Goddard in 1932, echoes this vegetarian sentiment. This book strongly influenced the growth of Buddhism in the English-speaking world during the 20th century. It is famous for its transformatory effect on beat writers such as Jack Kerouac. “The reason for practicing dhyana (meditation) and seeking to attain samadhi (mystic contemplation) is to escape from the suffering of life, ” writes Goddard. “But in seeking to escape from suffering ourselves, why should we inflict it upon others? How can a bhikshu (seeker), who hopes to become a deliverer of others, himself be living on the flesh of other sentient beings?”

The vegetarian flavor of the faith found fertile fields when Buddhism spread to China and Japan, where a nonviolent, meat-free culture had long been an established way of life. According to The Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, “In China and Japan the eating of meat was looked upon as an evil and was ostracized. The eating of meat gradually ceased and this tended to become general. It became a matter of course not to use any kind of meat in the meals of temples and monasteries.”

Buddhism entered China during the Han dynasty (206 bce–220 ce) when Confucianism and Taoism were already well established. The Chinese worshiped ancestral deities and followed strict dietary rules. Certain foods–pork, for example–were said to make the breath “obnoxious to the ancestors ” and were frowned upon.

Ancient Japanese lived primarily on vegetables, rice and grains. When Buddhism began to gain a stronghold in Japan during the sixth century, the nation had already absorbed much of Chinese culture. Chinese Buddhism blended compatibly with the Shintoism of Japan, which was significantly vegetarian. According to Shinto tradition, no animal food is offered at a shrine, as it is taboo to shed blood in a sacred place. Today, the Buddhism of Japan constitutes a merge of Shintoism with Chinese Buddhism. Although eating meat, especially fish, is common in the Japanese Buddhist community, the deeply religious still consider it an inferior practice. No meat or fish is ever consumed in a Zen Buddhist monastery.

Today, most Buddhists are not vegetarian, though contemporary Buddhist movements, such as Buddhists Concerned for Animal Rights, are seeking to reestablish vegetarian ideals. One Buddhist denomination, called the Cao Dai sect, has two million vegetarian followers.

The greatest progress of righteousness among men comes from the exhortation in favour of non-injury to life and abstention from killing. The Edicts of Ashoka

JUDAISM

JEWISH SCHOLARS BELIEVE GOD INTENDED MAN TO BE VEGETARIAN

Although ancient Hebrews ate meat, they did so sparingly. This restraint was not religiously or even ethically motivated. Meat was expensive and its consumption was a luxury. As an agrarian society, biblical Jews used animals mainly for labor and were largely vegetarian. They also consumed a great quantity of milk and milk products, mainly from sheep and goats.

Today most Jews live on a predominantly meat-based diet. A typical Jewish simcha (private celebration) consists of brisket, gefilte fish cakes, fish and chicken soup or chopped liver. Roberta Kalechofsky points out in Vegetarian Judaism–A Guide for Everyone that “Western Jews have historically eaten as much meat as the non-Jews; and due to their growing prosperity, European Jews have started to fully identify themselves with the meat-based diet.”

Scholars of Judaism agree that God’s intention was for man to be vegetarian. “God did not permit Adam and his wife to kill a creature and to eat its flesh,” said Rashi, a highly respected, 12th-century, Jewish rabbi who wrote the first comprehensive commentaries on the Talmud and Tanakh. Ronald Isaacs states in Animals in Jewish Thought and Tradition that all Talmudic rabbis conclude that “the permission to eat meat [was granted to human kind] as a compromise, a divine concession to human weakness and human need.” Rabbi Elijah Judah Schochet, in Animal Life in Jewish Tradition, notes that “scripture does not command the Israelite to eat meat, but permits this diet as a concession to lust.”

Jewish dietary laws are unique in including a prohibition against mixing meat and milk: “You shall not seethe a kid in its mother’s milk ” (Exodus 23:19). This mandate of not boiling a young goat in the milk of its mother is an elaboration of the command against cruelty to animals. Also, because offering meat boiled in milk was a pagan form of hospitality, Jews saw ruling against the practice as a way of distancing themselves from pagan ways.

Judaism prohibits the consumption of blood: “Only flesh with the life thereof, which is the blood thereof, shall you not eat ” (Genesis 9:4). “You shall eat the blood of no manner of flesh; for the life of all flesh is the blood thereof ” Leviticus 17:14). The rationale behind this injunction is that life belongs to God, and blood is life. “Blood is the life, and you shall not eat the life with the flesh ” (Deuteronomy 12:23).

In Jewish tradition, only certain animals are suitable as food. According to Elijah Schochet in his book Animal Life in Jewish Tradition: “Only quadrupeds which chewed their cud and had parted hoofs, such as the cow, sheep, goat, gazelle and male deer, were fit for food, these being by and large the herbivorous ruminants. Animals possessing only one of the two required characteristics, however, such as the camel, the badger and the pig, were forbidden, as of course, were animals which neither had split hoofs nor chewed their cud. Animals which died of natural causes were prohibited, as were those torn by wild beasts. Only fish possessing both fins and scales were permitted, while the majority of insects were forbidden. All land creatures that crawled on their bellies or moved on many feet were prohibited. Numerous birds were outlawed, notably predatory fowl and wild waterfowl.”

Jewish scholars cite three characteristics that distinguish animals as not suitable for slaughter as kosher meat: 1) that they are injurious to health, 2) that they are aesthetically repulsive and 3) that they serve as symbolic reminders to Jews of their status as holy people. Rabbinical authority states that these guidelines are to be obeyed in order that Israel should be “a holy people unto the Lord, ” and “distinguished from other nations by the avoidance of unclean and abominable things that defile them.”

The Bible does not provide direct support for the various Jewish dietary laws pertaining to the koshering process. Still, ritual slaughter (shechitah) is one of the central elements of kashrut (Jewish dietary laws). Kashrut decrees that an animal’s throat must be cut with a single, swift, uninterrupted horizontal sweep of a perfectly smooth knife in such a way as to sever the trachea, esophagus, carotid arteries and jugular vein. The profuse loss of blood is supposed to render the animal unconscious quickly, thus minimizing suffering.

Cruelty can be measured by the length of time it takes for an animal to die. One study performed by the English Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals concluded that “there is often a time-lag of anything from seventeen seconds to six minutes from the moment the animal’s throat is cut until it actually loses consciousness. Although the throat may be cut, the animal is by no means free from pain and can in some cases have a considerable awareness of what is happening.” Clearly, Judaism’s animal slaughter for food is difficult to reconcile with its pro-vegetarian interpretation of the Torah and its mandate to not inflict pain on any living being.

Jewish dietary laws apply only to animal foods. All fruits, vegetables, unprocessed grains–and anything that does not contain meat or milk products–are intrinsically kosher. Making meat kosher involves a complex process of removing all blood from the flesh. The butcher must remove veins, sacs and various membranes that collect blood, then soak, salt and rinse the meat to extract any remaining blood. Some authorities point out, however, that while koshering removes blood from the larger blood vessels, it does not extract it from the smallest vessels, such as the capillaries.

Today, the number of Jewish vegetarians is increasing. Advocates promote the Jewish teaching that “humans are partners with God in the preservation of life and health.”

“The removal of blood [from meat] is one the most powerful means of making us constantly aware of the concession and compromise which the whole act of eating meat, in reality, is.” The Jewish Dietary Law by Rabbi Samuel Dresner

ISLAM

IN A RELIGION THAT PRAISES THE PLEASURES OF MEAT, A FEW GO VEGETARIAN

In ancient times, meat-eating in Islamic countries was predicated on necessity. Pre-Islamic Arabs led a pastoral and nomadic existence in harsh desert climates where it would have been challenging, if not impossible, to survive on a vegetarian diet.

When Islamic civilization spread into Asia in the eighth century, meat-eating became an important symbol of difference, separating them from the predominantly vegetarian Buddhist and Hindu faiths and practices.

Muslims adhere to dietary regulations which are similar to those of Jews. Forbidden foods, referred to as haram, are blood, pork and those animals that have not been slaughtered by cutting the jugular vein with a very sharp knife while reciting a prayer pronouncing the name of Allah.

According to his earliest biographies, the Prophet Mohammed preferred vegetarian food, particularly favoring milk blended with yogurt, butter, nuts, cucumber, dates, pomegranates, grapes, figs and honey.

Mohammed was said to have been compassionate toward animals, and Islamic scriptures often command that all creatures be treated with care. According to Islamic tradition, no creature should be harmed in Mecca, the birthplace of Mohammed.

The Qur’an states that animals are like humans: “There is not an animal on earth, nor a bird that flies on its wings–but that they are communities like you. Nothing have We omitted from the Book, and they all shall be gathered to their Lord in the end.”

Richard C. Foltz writes in Animals in Islamic Tradition and Muslim Cultures: “[Even though] in mainstream Islam there is a tendency to see animals in terms of how they serve human interests, animals are to be valued, cared for, protected and acknowledged as having certain rights, needs and desires of their own. Their case is like that of human slaves albeit lower in the hierarchical scheme of things.”

Some customs of the Sufis, an offshoot of Islam, recommend abstention from meat-eating for bodily purification. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, a teacher in a 20th century school of Sufism, referred to as the Sri Lankan Qadiri, taught that the consumption of meat stimulates the animal nature, while the consumption of plant and dairy products brings peace. Chishti Inayat Khan, who helped introduce Sufi principles to Europe and America in modern times, observed that vegetarianism not only promotes compassion toward living creatures, it provides an important aid in the purification of the body for spiritual practices.

Nearly all of today’s 1.4 billion Muslims eat meat. The practice is justified by the logic that “one must not forbid something which Allah permitted.” According to the Qur’an, meat eating is one of the delights of heaven.

Some Islamic legal scholars assert that vegetarianism is actually not allowed by Islam. According to Mawil Izzi Dien in The Environmental Dimensions of Islam, “In Islamic law, there are no grounds upon which one can argue that animals should not be killed for food. & Muslims are not only prohibited from eating certain foods, but also may not choose to prohibit themselves food that is allowed by Islam. Accordingly, vegetarianism is not permitted unless on grounds such as unavailability or medical necessity.”

A few stalwart Muslim jurists insist that there should be no prohibition of vegetarianism in Islam and have actually issued legal rulings, known as fatwas, to this effect, asserting that Muslims may choose to be vegetarian, provided they realize and acknowledge that eating meat is allowed, and that vegetarianism will not bring them closer to Allah.

Iran has at least one vegetarian society. Turkey has several national vegetarian organizations. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has, at the suggestion of its Muslim members, launched a web site on Islam and vegetarianism.

Muslims who choose to abstain from eating meat do so for a variety of reasons. Some argue that, especially in the West, truly halal meat does not and cannot exist–that making meat halal is impossible in today’s industrialized world of factory farming. Even if the technical requirements of a halal slaughter are observed, the animals are not raised in humane and wholesome environments. They are physically abused and may be killed within view of other animals.

Some Muslims are choosing vegetarian lifestyles more for reasons of good health than upon religious principle. Dr. Shahid Athar of Indiana University School of Medicine asserts in www.IslamicConcern.com: “There is no doubt that a vegetarian diet is healthier.”

Others are turning to vegetarianism because of the deleterious effect meat-eating has on the environment. Industrial meat production may render meat haram (Islamically unlawful), because it leads to environmental collapse and destruction. The Qur’an (7:56) states, “Waste not by excess, for Allah loves not the wasters, ” and “Do not pollute the earth after it has been (so) wholesomely (set in order).”

Muslims in the West face additional challenges in following dietary mandates of their faith. Halal meat is often not readily available. Restaurant and pre-packaged foods may contain forbidden ingredients. One option in the face of these challenges is a vegetarian meal, which avoids restricted ingredients. While some Muslims conclude that simply abstaining from eating meat is an obvious solution, others are adamant that following Islamic dietary law is far more complicated than just being vegetarian.

“In all that has been revealed unto me, I do not find anything forbidden to eat, unless it be carrion, or blood poured forth, or the flesh of swine.” Qur’an 5:3, 2:173, 6:145

CHRISTIANITY

BOTH VEGETARIANS AND MEAT-EATERS FIND SUPPORT IN SCRIPTURES

Most modern Christians believe in the “dominion perspective, ” an exclusively Christian theological stance asserting that human life has greater value than animal life and that all of nature exists for the sole purpose of serving the needs and interests of man. This perspective gained significant development and fortification from famous philosophers and theologians like Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas and Descartes. Descartes asserted that animals were “automata,” souless entities with no capacity to experience suffering.

Unlike the Jewish Torah, the New Testament sets no moral guidelines for man in dealing with animals. Apostle Paul, commenting on the Torah’s restriction of muzzling an ox that threshes corn, observed: “Does God care for oxen? Of course not. [Their purpose] is altogether for our sakes.” (1 Corinthians. 9:9-10)

The Old Testament, known also as the Hebrew Bible, is the first part of the Christian Bible. Therefore, Jews and Christians share the concept that in the beginning, symbolized in the story of the Garden of Eden, mankind was nonviolent and vegetarian, later becoming corrupt, symbolized by the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden.

Genesis 9:1-3 is the most significant Biblical text supporting the Christian tradition of eating meat. This famous verse states that “God blessed Noah and his sons, and said to them: ‘Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. The fear and dread of you shall rest on every animal of the earth, and on every bird of the air, on everything that creeps on the ground, and on all the fish in the sea; into your hand they are delivered. Every moving thing that lives shall be food for you; and just as I gave you the green plants, I give you everything.’ ”

If rabbinical literature interprets Genesis 9:3 as divine concession to human weakness and human need, Christians consider it clear and unconditional approval of the consumption of animal flesh.

It is clear from the teachings of the New Testament that Christian tradition came to interpret in the teachings of Christ an express authorization to freely eat meat: “Thus, he declared all foods clean.” (Mark 7:19) This assessment is further rationalized with the argument that Jesus put much greater emphasis on man’s deeds than on his diet. It has also been postulated that, as a radical reformer, Jesus wanted to distance himself from the formalism of the Jewish faith, and that moving away from Jewish dietary laws toward a more virtue-based ethic might highlight this shift.

There are varying opinions with regard to whether or not Jesus himself ate meat. According to the Bible, he at least ate fish: “And when he said this, he showed them his hands and his feet. While in their joy they were disbelieving and still wondering, he said to them, ‘Have you anything here to eat?’ They gave him a piece of broiled fish, and he took it and ate in their presence.” (Luke 24:40-43).

Christians seeking further justification for their meat-based dietary preferences cite many examples in The New Testament where Jesus asks for meat. Some scholars deny the validity of these citations, asserting that a closer study of the original Greek text reveals that the words understood as “meat ” would more accurately be translated as “food.” Also, it has been asserted by some experts that fish in this context could also mean little bread rolls made from a submarine plant known as the “fish plant.” These soft plants were dried in the sun, ground into flour and baked into rolls. Fish-plant rolls were a significant feature of the ancient Babylonian diet.

There is a strong opinion among some scholars that the original teachings of Jesus were altered by the Church, particularly by the “correctors ” who were appointed by ecclesiastical authorities of Nicea in 325 ce. Those scholars believe that these “corrections ” most blatantly misrepresented the teachings of Jesus with regard to violence and meat-eating. In his foreword to the translation of The Gospel of the Holy Twelve, Rev. G.J. Ousley writes: “What these correctors did was to cut out of the Gospels, with minute care, certain teachings of our Lord which they did not propose to follow namely, those against the eating of flesh and the taking of strong drink.”

Scholars tend to agree that many early Christians were vegetarians. St. John Chrysostom wrote: “We, the Christian leaders, practice abstinence from the flesh of animals to subdue our bodies.” Some experts assert that Matthew and all the Apostles abstained from eating meat.

Prior to the Middle Ages, several monastic orders adhered to vegetarianism, including the Augustinian, Franciscan and Cistercian orders. With time, however, organized Christianity moved away from these vegetarian roots. Meat-eating was so much an accepted way of life during the time of the Roman Empire that vegetarian Christians had to follow their culinary choices in secrecy.

Before the end of the 18th century, John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church, was the only major Christian leader who was a vegetarian. In 1809, in Safford, England, Reverend William Cowherd started the Bible Christian Church, Europe’s first vegetarian church in recent times. By 1817, Reverend Cowherd’s nephew, Reverend William Metcalfe, established a branch of this church in Philadelphia, bringing vegetarianism onto American soil.

More recently, several notable personages have adopted and/or encouraged vegetarianism. after: These include Ellen G. White, one of the founders of the Seventh Day Adventists; Dr. Albert Schweitzer, Nobel Peace Prize winner, theologian, musician and philosopher; Dr. John H. Kellogg, creator of corn flakes; Reverend Fred Rogers, host of TV show “Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood; ” and Reverend Sylvester Graham, creator of graham crackers.

Reverend Sylvester Graham was a Presbyterian minister. He launched a modern food reform, campaigning to assure that essential nutrients were not removed from vegetarian foods. The Seventh day Adventists were the first official vegetarian Christians. Today, half of all Seven Day Adventists are vegetarian. The Trappist, Benedictine and Carthusian Orders of the Roman Catholic Church are also vegetarians.

A growing number of modern Christians not only perceive vegetarianism as being in consonance with core principles of Christianity, they also see it as at least a partial relief to problems like poor health, world hunger and global economy.

“Thou shalt not kill.” Exodus 20:13

SIKHISM

THE FIRST SIKH GURU ESTABLISHED VEGETARIAN COMMUNITY KITCHENS

Scholars perceive Sikhism as a syncretic faith that combines elements of Hinduism and Islam. The Sikh religion began in the 16th century in northern India with the teachings of Guru Nanak and was continued by the nine gurus that followed him. Today most of the world’s Sikh population live in the Indian state of Punjab. They are mostly meat-eaters, but a predilection for vegetarianism has been present from the faith’s beginning.

According to Sikh scholar Swaran Singh Sanehi of the Academy of Namdhari Culture: “Sikh scriptures support vegetarianism fully. Sikhs living during the time of Guru Nanak had adopted the Hindu tradition and way of living in many ways. Their dislike for flesh-foods arose from that tradition. Guru Nanak considered meat-eating improper.”

Nanak instituted a tradition of free community kitchens, lungar (still flourishing today) where anyone–regardless of race, religion, gender or caste–can enjoy a simple meal. This was inspired by a belief in the equality of all men and rejection of the Hindu caste system. Such kitchens serve vegetarian food twice a day, every day of the year. Being vegetarian, the meals are acceptable to to people from different religions and cultures. These lungars have been appreciated during times of disaster, such as following the 2005 tsunami and Hurricane Katrina.

In the Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, meat consumption is strongly condemned in passages like the following: “You kill living beings, and call it a righteous action. Tell me, brother, what would you call an unrighteous action?”

Sikhs rigorously denounce animal sacrifice as well. This includes ritual slaughter to sanctify meat for eating, as in the preparation of halal or kosher meat.

The Indian saint and mystic Kabir, a contemporary of Guru Nanak who some believe may have been Nanak’s preceptor, wrote: “If you say that God resides in all, why do you kill a hen? & It is foolish to kill an animal by cruelty and call that dead animal sanctified food. & You keep fasts in order to become acceptable to God, but kill a living animal for your relish.”

The ten Gurus of Sikhism neither condoned nor condemned meat-eating in a formal way. Although they felt that it was unnecessary to kill animals and birds for food, they did not believe vegetarianism should become dogma. They emphasized controlling the contents of the mind more than controlling the contents of the body. Guru Nanak apparently considered it futile to argue about food. When pressed to comment on meat-eating, he said, “Only the foolish quarrel over the desirability of eating flesh. They are oblivious to true knowledge and meditation. What is flesh? What is vegetable? Which is sin-infested? Who can say what is good food and that which leads to sin?” Today, some Sikhs avoid beef and pork, observing the meat prohibitions of both Islam and Hinduism. Other groups, such as the Namdharis and Yogi Bhajan’s 3HO Golden Temple Movement, are strictly vegetarian.

ZOROASTRIANISM

ZOROASTER INSPIRED COMPASSION THROUGH THE PRACTICE OF VIRTUE

Zoroastrianism (sometimes called Magianism, Mazdaism or Parseeism) was founded in ancient Persia by the prophet Zoroaster, also known as Zarathushtra. Although estimates for the birth of Zoroaster vary greatly, it is popularly accepted that he lived in pastoral Iran around 600 bce and was an ardent advocate of vegetarianism when it was not customary to be so. According to Colin Spencer in The Heretic’s Feast, Zoroaster was not only a vegetarian, he also disavowed animal sacrifice.

Zoroaster emphasized moderation. With regard to food, this meant not eating too much–such as in gluttony, or too little–such as in fasting. He also taught compassion through the kind treatment of all living entities.

Zoroastrians have always had a great respect for nature. Today, this benevolence is incorporated into a lifestyle that highlights striving to live with a sensitivity to the soul force vibrant in all things. Zoroastrian festivals celebrate six seasons of the year, which correspond to six periods of creation in nature: mid-spring, mid-summer, the season of corn, the season of flocks, winter solstice and the fire festival of sacrifices.

In the ninth century, the High Priest Atrupat-e Emetan recorded in Denkard, Book VI, his request for Zoroastrians to be vegetarians: “Be plant eaters, O you men, so that you may live long. Keep away from the body of the cattle, and deeply reckon that Ohrmazd, the Lord, has created plants in great number for helping cattle and men.”

Zoroastrian scriptures assert that when the “final Savior of the world ” arrives, men will give up meat eating.

Jane Srivastava holds a bachelor’s degree from Vilnius State University, Lithuania, and a degree from the Albany Law School, Albany, New York. She now lives in South Carolina.

Dear Writer,

Please put the context more strongly on emphasis for not eating meat tied to Moskha. The reason why meat eating was allowed in Vedas was to curtail the habit, not endorse it.

Please read Swaminarayan Faith holy scripture called Vachanmrut, Chapter Gadadha I-69. In it Shriji Maharaj, whom I believe to me my “ista-dev” says that “Dharma, aartha, kama can be achieved by path of violence”… but “Moskha can only be attained by non-violence.”

Today, the Indian Hindu must choose… if they want to keep India… Land of Sages, or let it become known as Land of Butchers.

The Hindu Satvic panths/sects/sampraday… must unite under “meat free India” goal and fundumental unity of Hindu above all other ritualistic differences; trying to figure out which God or Godesses is supreme. If The Hindu does not unite on this no killing of animals for food/sacrifice….in the land of Bharat/India. The fabric of Sanathan Dharma will be erased. India must stay the land of Hindu and a becon for those who seek spirituality/Moskha.

So write to unite the Hindu faiths. Call the leaders of each sect/sampraday… and ask them to promote non-violence Yagna and sermons regarding to their followers… take back the country towards 100 percent meat free nation. All issues of current times will be solved, really bring back to Godhead… then see the grace of Gods/Goddesses on India… we will become 20 trillion economy… not the 5 trillion being enslaved by the western and non-veg society.

The veg vs. non veg has always been an epic clash… which in modern times been glazed over by showing that Hindu does not condone meat eating. This is wrong… king Asokha almost made India meat free country. Etc… so stop this false interpertarion. Hindu is always preached vegetarian. Krishna treated cows very well; only took a portion of some milk from many cows in return for fresh grass for the calf. Let not go and associate that ideal vegetarianism is wrong too. The current factory farming needs to change… so lets work on that too…

For those who seek god/ or have seen god; three elements must be seen per my understanding.

1. Firm belief of not killing of all animals for food/sacrifices.

2. Penance; self-restraint; bhramcharaya to the fullest extent possible within the stage of life.

3. True Bhakti; unconditional.